The Temple Murals: the Life of Malcolm X by Florian Jenkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Finding Aid to the Jeff Donaldson Papers, 1918-2005, Bulk 1960S-2005, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Jeff Donaldson Papers, 1918-2005, bulk 1960s-2005, in the Archives of American Art Erin Kinhart and Stephanie Ashley Funding for the digitization of the Jeff Donaldson papers was provided by the Walton Family Foundation. 2018 November 1 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1954-2004............................................................. 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1957-2004.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Interviews, -

Group Interview with Africobra Founders

Group interview with AfriCOBRA founders Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The original format for this document is Microsoft Word 11.5.3. Some formatting has been lost in web presentation. Speakers are indicated by their initials. Interview Group Interview Part 1 AFRICOBRA Interviews Tape GR3 TV LAND GROUP INTERVIEW: BARBARA JONES HOGU, NAPOLEON JONES HENDERSON, HOWARD MALLORY, CAROLYN LAWRENCE, MICHAEL HARRIS Note: Question difficult to hear at times. Also has heavy accent. BJH: I don't think (Laughter) ... I don't think the Wall of Respect motivated AFRICOBRA. The Wall of Respect started first, and it was only after that ended that Jeff called some of the artists together and ordered to start working on the idea of philosophy in terms of creating imagery. You know, recently I read an article that said that the AFRICOBRA started at the Wall of Respect and I'd ... it's just said that some of the artists that worked on the Wall of Respect became AFRICOBRA members. You know, but the conception of AFRICOBRA did not start at the Wall of Respect. MH: How different was it than OBAC? What was going on in OBAC? BJH: Well, OBAC is what created the Wall of Respect. MH: Right. Q: Right. BJH: Yeah, that was dealing with culture. MH: But in terms of the outlook of the artists and all of that, how different was OBAC's outlook than what came to be AFRICOBRA? BJH: Well, OBAC didn't have a philosophy, per se. -

Newyork 08-1

Representative Hakeem Jeffries 117th United States Congress New York's 8TH Congressional District NUMBER OF DELIVERY SITES IN 37 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT (main organization in bold) BEDFORD STUYVESANT FAMILY HEALTH CENTER, INC., THE Broadway Family Health Center - 1238 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-2906 PS 256 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 114 Kosciuszko St Brooklyn, NY 11216-1007 PS 309 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 794 Monroe St Brooklyn, NY 11221-3501 PS 54 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 195 Sandford St Brooklyn, NY 11205-4525 BETANCES HEALTH CENTER Betances Health Center at Bushwick - 1427 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-4202 BROOKLYN PLAZA MEDICAL CENTER Benjamin Banneker Academy Sbh - 77 Clinton Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2302 Whitman, Ingersoll, Farragut H C - 297 Myrtle Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2901 BROWNSVILLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION BMS Dental@Genesis - 330 Hinsdale St Brooklyn, NY 11207-4518 BMS@Ashford - 650 Ashford St Brooklyn, NY 11207-7315 BMS@Genesis - 360 Snediker Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4552 BMS@Jefferson High School Campus - 400 Pennsylvania Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4707 CARE FOR THE HOMELESS Bushwick Family Residence - 1675 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11207-1495 Care Found Here: Junius St - 91 Junius St Brooklyn, NY 11212-8021 St. John's Bread and Life - 795 Lexington Ave Brooklyn, NY 11221-2903 COMMUNITY HEALTHCARE NETWORK, INC. Dr Betty Shabazz Health Center - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (3) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (4) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 FLOATING HOSPITAL INCORPORATED (THE) Auburn Assessment Center - 39 Auburn Pl Brooklyn, NY 11205-1946 Flatlands - 10875 Avenue D Brooklyn, NY 11236-1931 Help I Family Center - 515 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4502 HOUSING WORKS HEALTH SERVICES III, INC. -

The Artistic Evolution of the Wall of Respect in His 1967 Poem, The

The Artistic Evolution of the Wall of Respect In his 1967 poem, The Wall, Don Lee/Haki Madhubuti described the Wall of Respect as “…a black creation / black art, of the people, / for the people, / art for people’s sake / black people / the mighty black wall ….” This essay describes how the Wall of Respect evolved to meet different definitions of “art for people’s sake” from 1967- 1971. The Origin of an Idea, Spring and Summer 1967 The Wall of Respect was the result of both collective action and individual inspiration. In the spring of 1967 a group of artists formed the multi-disciplinary Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC). Many of OBAC’s members were college graduates or art students who wanted to involve their art in the collective political struggles of the era. They established a visual arts workshop headed by artist Jeff Donaldson with the goal of producing a significant collective artwork. But it was the slightly older mural painter Bill Walker who introduced the idea of painting a public work of art on the corner of 43rd Street and Langley Avenue. Walker had been planning on painting a mural by himself that would address the neighborhood’s impoverished condition and upon joining OBAC he presented the idea to the group. The other artists responded with enthusiasm to the general idea; however, they cooperatively decided that the project should involve everyone in the Visual Arts Workshop and focus on the more optimistic theme of “Black Heroes.” As Donaldson pointed out, the very act of making public portraits of black heroes was a radical undertaking during an era when advertisements and school textbooks rarely featured African Americans and the mainstream media rarely reported positive stories about the black community. -

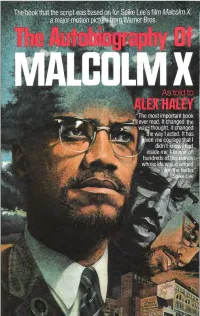

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

Art for People's Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965

Art/African American studies Art for People’s Sake for People’s Art REBECCA ZORACH In the 1960s and early 1970s, Chicago witnessed a remarkable flourishing Art for of visual arts associated with the Black Arts Movement. From the painting of murals as a way to reclaim public space and the establishment of inde- pendent community art centers to the work of the AFRICOBRA collective People’s Sake: and Black filmmakers, artists on Chicago’s South and West Sides built a vision of art as service to the people. In Art for People’s Sake Rebecca Zor- ach traces the little-told story of the visual arts of the Black Arts Movement Artists and in Chicago, showing how artistic innovations responded to decades of rac- ist urban planning that left Black neighborhoods sites of economic depres- sion, infrastructural decay, and violence. Working with community leaders, Community in children, activists, gang members, and everyday people, artists developed a way of using art to help empower and represent themselves. Showcas- REBECCA ZORACH Black Chicago, ing the depth and sophistication of the visual arts in Chicago at this time, Zorach demonstrates the crucial role of aesthetics and artistic practice in the mobilization of Black radical politics during the Black Power era. 1965–1975 “ Rebecca Zorach has written a breathtaking book. The confluence of the cultural and political production generated through the Black Arts Move- ment in Chicago is often overshadowed by the artistic largesse of the Amer- ican coasts. No longer. Zorach brings to life the gorgeous dialectic of the street and the artist forged in the crucible of Black Chicago. -

The Black Power Movement

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 1: Amiri Baraka from Black Arts to Black Radicalism Editorial Adviser Komozi Woodard Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. ISBN 1-55655-834-1 1. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—Sources. 3. Black nationalism—United States— History—20th century—Sources. 4. Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934– —Archives. I. Woodard, Komozi. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . Guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. IV. Title: Amiri Baraka from black arts to Black radicalism. V. Series. E185.615 323.1'196073'09045—dc21 00-068556 CIP Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-834-1. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

BROOKLYN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 16 Oversight Block Lot Facility Name Facility Address Facility Type Capacity / Type Agency

Selected Facilities and Program Sites Page 1 of 17 in New York City, release 2015 BROOKLYN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 16 Oversight Block Lot Facility Name Facility Address Facility Type Capacity / Type Agency SCHOOLS Public Elementary and Secondary Schools 3693 1CHRISTOPHER AVENUE COMMUNITY 51 Christopher Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 240 Children NYC DOE SCHOOL 1457 32DR JACQUELINE PEEK‐DAVIS SCHOOL 430 Howard Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 208 Children NYC DOE 3597 11GENERAL D CHAPPIE JAMES ELEM SCHOOL 76 Riverdale Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 96 Children NYC DOE 3744 9PS 150 CHRISTOPHER 364 Sackman St Elementary School ‐ Public 214 Children NYC DOE 3535 16PS 156 WAVERLY 104 Sutter Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 781 Children NYC DOE 3622 23PS 165 IDA POSNER 76 Lott Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 481 Children NYC DOE 1440 56PS 178 SAINT CLAIR MCKELWAY 2163 Dean St Elementary School ‐ Public 460 Children NYC DOE 3606 1PS 184 NEWPORT 273 Newport St Elementary School ‐ Public 567 Children NYC DOE 3544 135PS 284 LEW WALLACE 213 Osborn St Elementary School ‐ Public 577 Children NYC DOE 3507 7PS 298 DR BETTY SHABAZZ 85 Watkins St Elementary School ‐ Public 294 Children NYC DOE 3520 8PS 327 DR ROSE B ENGLISH 111 Bristol St Elementary School ‐ Public 633 Children NYC DOE 3693 1PS 332 CHARLES H HOUSTON 51 Christopher Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 23 Children NYC DOE 3604 1PS 41 FRANCIS WHITE 411 Thatford Ave Elementary School ‐ Public 550 Children NYC DOE 1528 1PS 73 THOMAS S BOYLAND 251 Mcdougal St Elementary School ‐ Public 191 Children NYC DOE -

INSIDE a Behind-The-Curtain Look at the Artists, the Company and the Art Form of This Production

This section is part of a full NEW VICTORY® SCHOOL TOOL® Resource Guide. For the complete guide, including information about the NEW VICTORY Education Department, check out: NewVictory.org/SchoolTool INSIDE A behind-the-curtain look at the artists, the company and the art form of this production COMMON CORE STANDARDS Reading: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10 Summary Writing: 1; 2; 3; 4; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10 Speaking and Listening: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6 In times of political unrest, must a man die for the greater good of the Language: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5 nation? The assassinations of Rome’s great ruler of the Republic and the revolutionary leader Malcolm X share the stage when New York’s NEW YORK STATE STANDARDS acclaimed The Acting Company pairs Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR with Arts: 1; 2; 3; 4 X: OR, BETTY SHABAZZ V. THE NATION a compelling new play by lauded English Language Arts: 1; 2; 3; 4 playwright Marcus Gardley (The House that Will Not Stand, The Gospel of Social Studies: 1; 2; 3; 4; 5 Lovingkindness, Every Tongue Confess, On The Levee). BLUEPRINT FOR THE ARTS Presented in repertory, each featuring the same outstanding cast, these Theater: Theater Making, two gripping dramas examine two charismatic leaders who rise only to Developing Theater Literacy, fall victim to rivalry, resentment and retribution. Exploring the tumultuous Making Connections, Visual Arts: Making Connections landscape of ideology and activism in the 1960s, X: OR, BETTY SHABAZZ V. THE NATION is directed by Ian Belknap, Artistic Director of The Acting Company. -

Congressional Record—House

H6772 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE September 3, 1997 GENERAL LEAVE trator in that college. This is the kind Ultimately, in addition to her profes- Ms. NORTON. Mr. Speaker, I ask of transformation aspect of her life sional stature, Betty was to become a unanimous consent that all Members that, in many ways, is shades of Mal- human rights advocate of very special may have 5 legislative days within colm. stature. which to revise and extend their re- b 2015 I want to say something further marks on my special order in recogni- about her husband, the man who trans- Betty met Malcolm in New York, formed himself from a petty criminal tion of the life of Betty Shabazz to be having come there to study nursing. given today. to a major league thug to a black Mus- She described the courtship as an old- lim and finally to an orthodox Sunni The SPEAKER pro tempore. Is there fashioned courtship. I wish we had objection to the request of the gentle- Muslim who embraced universal broth- more of those today. Malcolm loved erhood, because I think we ought to be woman from the District of Columbia? children, and he particularly loved his There was no objection. clear who Malcolm became. There is children. I must say that during their lack of clarity on that in this country, f what turned out to be a short mar- because only then can we understand riage, Betty was pregnant most of the RECOGNIZING THE LIFE OF BETTY Betty Shabazz. time. SHABAZZ But before I go on, I see that I have Malcolm was assassinated on Feb- been joined by my good colleague, the The SPEAKER pro tempore. -

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College Commencement Exercises SUNDAY, JUNE NINTH NINETEEN HUNDRED NINETY-SIX HANOVER'E~ NEW HAMPSHIRE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE ORDER OF EXERCISES James Oliver Freedman, President Stephen Merrill, Governor of New Hampshire (ex officio) PROCESSIONAL Edward John Rosenwald Jr., Chair Stephen Warren Bosworth Music by The Hartt College Brass Ensemble Joseph Deyo Mathewson Stanford Augustus Roman Jr. Roger Murtha, Director Kate Stith-Cabranes Susan Grace Dentzer Andrew Clark Sigler David Marks Shribman So that all can see the procession, the audience is requested to remain seated except as the flags pass when the audience rises briefly Richard Morton Page David Karr Shipler William Haven King Jr. Peter Matthew Fahey The presence of the Brass Ensemble at Commencement each year is made possible by the Class of 1879 Trumpeters' Fund. The Fund was established in 1929, Barry Lee MacLean Jonathan Newcomb at the time of 1879'sfiftieth reunion OPENING PRAYER Gwendolyn Susan King, Christian Chaplain The Academic Procession The Academic Procession is headed by the Platform Group, led by the Dean of the SINGING OF MILTON'S PARAPHRASE OF PSALM CXXXVI College, as Chief Marshal. Marching behind the Chief Marshal is the President of the College, followed by the Acting President and the Provost. Dartmouth College Glee Club Behind them comes the Bezaleel Woodward Fellow, as College Usher, bearing Lord Louis George Burkot Jr., Conductor Dartmouth's Cup. The cup, long an heirloom of succeeding Earls of Dartmouth, was presented to the College by the ninth Earl in 1969. Dartmouth College Chamber Singers The Trustees of the College march as a group, and are followed by the Vice President Melinda Pauly O'Neal, Conductor and Treasurer, in her capacity as College Steward. -

Free Summer Meals Nyc 2021

FREE SUMMER MEALS NYC 2021 As of 7/12/2021 - Locations, dates and times are subject to change Summer End Community Halal NYCHA Region District School-Name Site - Address City Zip Notes Date Feeder Kosher Yes Halal M 1 P.S. 020 Anna Silver 166 ESSEX STREET MANHATTAN 10002 8/20/2021 Yes M 1 East Side Community School 420 East 12 Street MANHATTAN 10009 8/20/2021 Yes M 1 The STAR Academy - P.S.63 121 EAST 3 STREET MANHATTAN 10009 8/20/2021 Yes Yes M 1 P.S. 064 Robert Simon 600 EAST 6 STREET MANHATTAN 10009 9/3/2021 Yes M 1 P.S. 110 Florence Nightingale 285 DELANCY STREET MANHATTAN 10002 8/20/2021 Yes Yes M 1 P.S. 142 Amalia Castro 100 ATTORNEY STREET MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes Yes M 1 P.S. 188 The Island School 442 EAST HOUSTON STREET MANHATTAN 10002 8/20/2021 Yes Yes M 1 Lower East Side Preparatory High Sch 145 STANTON STREET MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes Yes M 1 University Neighborhood Middle Schoo 220 HENRY STREET MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes Yes M 1 New Design High School 350 GRAND STREET MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes Yes M 1 New Explorations into Science, Techn 111 COLUMBIA STREET MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes M 1 Hamilton Fish Pool 128 Pitt Street MANHATTAN 10002 9/3/2021 Yes M 1 Tompkins Mini Pool 9th Street and Avenue A. MANHATTAN 10009 9/3/2021 Yes M 1 Dry Dock Pool Easy 10th Street between Ave C and D MANHATTAN 10009 9/3/2021 Yes M 2 P.S.