Conflict in South Kordofan: the Complexity of Sudan's Interlocking Crises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

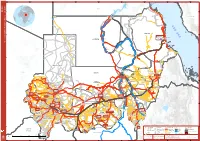

South West of Sudan and North-East South-Sudan - OCBA Projects KHARTOUM NORTH SHENDI 16°0'0"N KARARI Khartum, Sudan EPP

SOUDAN - South West of Sudan and North-East South-Sudan - OCBA projects KHARTOUM NORTH SHENDI 16°0'0"N KARARI Khartum, Sudan EPP Nile Project UMM BADDA Cell: OC5 SHARQ EL NILE Project code: ESSD160 Omdurman Dates: 1/1/2016 - 31/12/2017 Khartoum UM DURMAN KHARTOUM EL BUTANA Khartoum, capital JABAL El Bahr e Coordination AULIA l Azra JEBRAT EL q SHEIKH Cell: OC5 Project code: ESSD101 EL KAMLEEN Dates: 30/4/2017 - 31/1272017 El Kamlin SODARI EASTERN EL GEZIRA El Qutainah EL HASAHEESA Rufa'ah Hamrat El El Hasahisa Jebrat El Sheikh EL Sheikh EL GAZIRA MALHA NORTH KORDOFAN UMM RAMTTA UM EL QURA Sodari GREATER EL GUTAINA WAD MADANI El Managil EL MANAGEEL SOUTHERN EL GEZIRA BARA Ad Duwaym 14°0'0"N EL DOUIEM NORTH DARFUR EASTERN Bara SENNAR Sennar UMM KEDDADA EL NEHOUD SENNAR RABAK SENNAR Kosti SINGA UM RAWABA KOSTI Khor Waral, Arrivals SHIEKAN Tandalti Project WAD BANDA Cell: OC5 ABU ZABAD Umm Rawaba TENDALTI Project code: ESSD184 WHITE NILE Dates: 20/4/2017 - 20/8/2017 El Rahad En Nehoud EL DALI ABU HOUJAR EL SALAM El Jebelain Dibebad EL JABALIAN AL QOZ Al Khashafa (White Nile), Displaced WEST KORDOFAN Abu Zabad Project Cell: OC5 Project code: ESSD112 Ghubaysh EL ABASSIYA Dates:1/1/2016 - 31/1272017 GHUBAYSH AL SUNUT Delling DILLING 12°0'0"N Habila RASHAD Dalami Rashad El Fula HABILA EL SALAM AL TADAMON Umm Heitan Abu Jubaiha Lagawa BLUE NILE El Buheimer LAGAWA REIF ASHARGI BABANUSA Heiban ABU JUBAIHA HEIBAN ADILA SOUTH Miri Juwa KORDOFAN KADUGLI BAU Umm Dorain Kologi Keilak UMM DUREIN AL BURAM Talodi NORTHERN UPPER ABYEI - Buram EL KURMUK MUGLAD -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

Sudan Food Security Outlook Report

SUDAN Food Security Outlook February to September 2019 Deteriorating macroeconomic conditions to drive high levels of acute food insecurity in 2019 KEY MESSAGES • Food security has seasonally improved with increased cereal Current food security outcomes, February 2019 availability following the November to February harvest. However, the macroeconomic situation remains very poor and is expected to further deteriorate throughout the projection period, and this will drive continued extremely high food and non-food prices. The negative impacts of high food prices will be somewhat mitigated by the fact that livestock prices and wage labor are also increasing, though overall purchasing power will remain below average. A higher number of households than is typical will face Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse outcomes through September. • Between June and September, the lean season in Sudan, Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected in parts of Red Sea, Kassala, Al Gadarif, Blue Nile, West Kordofan, North Kordofan, South Kordofan, and Greater Darfur. Of highest concern are the IDPs in SPLM-N controlled areas of South Kordofan and SPLA-AW controlled areas of Jebel Marra, who have been inaccessible for both assessments and food assistance deliveries. IDPs in these areas are expected to be in Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC-compatible analysis follows Emergency (IPC Phase 4) during the August-September peak key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national of the lean season. food security partners. • The June to September 2019 rainy season is forecasted to be above average. This is anticipated to lead to flooding in mid-2019 and increase the prevalence of waterborne disease. -

Sudan's Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile Africa Report N°204 | 18 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Sudan in Miniature ....................................................................................................... 3 A. Old-Timers Versus Newcomers ................................................................................. 3 B. A History of Land Grabbing and Exploitation .......................................................... 5 C. Twenty Years of War in Blue Nile (1985-2005) ........................................................ 7 III. Failure of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ............................................................. 9 A. The Only State with an Opposition Governor (2007-2011) ...................................... 9 B. The 2010 Disputed Elections ..................................................................................... 9 C. Failed Popular Consultations ................................................................................... -

Amir Warns Against Oil Dependence, Terrorism

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2014 MUHARRAM 5, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Amir on Bahrain Macy’s heads Anelka makes brotherly bans main overseas with nightmarish visit to opposition branch in comeback Saudi Arabia3 group 7 Abu21 Dhabi in19 India Amir warns against oil Max 33º Min 21º dependence, terrorism High Tide 01:50 & 16:10 Low Tide PM calls to ‘tighten belts’ Speaker blasts opposition 09:25 & 21:25 40 PAGES NO: 16326 150 FILS • from the editor’s desk It’s time to get to work By Abd Al-Rahman Al-Alyan [email protected] is Highness the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah opened the 14th Hsession of Kuwait’s National Assembly yes- terday, urging lawmakers and the government to control spending and diversify Kuwait’s economy in the face of falling oil prices. “Here again, we are witnessing another cycle of sliding oil prices as a result of economic and politi- cal factors hitting the global economy, which is negatively affecting the national economy,” the KUWAIT: (From left) HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah, HH the Prime Minister Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah and Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanem attend the opening session of the new parliamentary term yesterday. — Photos by Yasser Al-Zayyat and KUNA Amir said. “I call on you, government and Assembly, to shoulder your national responsibility to issue the required legislation and decisions to By B Izzak safeguard our oil and fiscal wealth which is not for KUWAIT: His Highness the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- us alone but also for our future generations,” Ahmad Al-Sabah yesterday opened the new parliamen- Sheikh Sabah said. -

(I): War in South Kordofan

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (I): War in South Kordofan Africa Report N°198 | 14 February 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Roots of Persistent Conflict ....................................................................................... 3 A. Continued Marginalisation ........................................................................................ 4 B. Changing Ethnic Dynamics ....................................................................................... 8 III. Failure of the CPA ............................................................................................................. 11 IV. Outbreak of Fighting and the Still-born Framework Agreement ................................... 17 V. All-Out Conflict ................................................................................................................ 20 VI. The Humanitarian Crisis .................................................................................................. 27 VII. Regional and Wider -

Very High Staple Food Prices to Continue Driving Large Assistance Needs Through Lean Season

SUDAN Food Security Outlook February to September 2020 Very high staple food prices to continue driving large assistance needs through lean season KEY MESSAGES • Large numbers of people are expected to face Crisis (IPC Phase Current food security outcomes, February 2020 3) or worse food security outcomes in Sudan through September 2020, particularly poor households and IDPs in Greater Darfur, Greater Kordofan, Red Sea and Kassala states. Of highest concern are IDPs and conflict-affected people in areas of Jebel Marra in Darfur and SPLM-N held areas of South Kordofan, parts of West Kordofan and Blue Nile where humanitarian access is poor and Emergency (IPC Phase 4) outcomes are expected between June and September 2020. • National cereal production for the 2019/20 season in Sudan is estimated at 5.1 million metric tons, 18 percent below the five- year average and 57 percent below last year’s bumper harvest. The decrease in cereal production this year is related to increases in area planted in cash crops at the expense of area planted in cereals, and to a lesser extent, low yields resulting from flooding and pest infestations. • Sudan’s persistent macroeconomic crisis has continued to Source: FEWS NET deteriorate further into February 2020 as reserves of foreign FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC-compatible analysis currency remain low, the SDG/USD exchange rate continues to follows key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect the consensus decline, prices of imported essential items remain very high. of national food security partners. Moreover, prices for locally produced staples continue to increase to very high levels. -

The Sudan | Agricultural Livelihoods and Food Security in the Context Of

THE SUDAN Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19 Monitoring Report January 2021 THE SUDAN Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19 Monitoring Report January 2021 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2021. The Sudan | Food supply, agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: Monitoring Report – January 2021. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2262en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN: 978-92-5-133670-0 © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Sudan's Southern Kordofan Problem: the Next Darfur?

SUDAN’S SOUTHERN KORDOFAN PROBLEM: THE NEXT DARFUR? Africa Report N°145 – 21 October 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. NUBA FRUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................. 2 A. DISSATISFACTION WITH THE CPA AND THE SPLM ......................................................................2 1. CPA uncertainties...................................................................................................................3 2. Discontent with SPLM leadership..........................................................................................4 B. NCP MANIPULATION...................................................................................................................5 1. Keeping control over state finances........................................................................................5 2. Census concerns .....................................................................................................................7 3. Real progress? ........................................................................................................................8 C. LAND GRIEVANCES......................................................................................................................9 D. STALLED DDR AND RISK OF NEW INSURGENCY ........................................................................11 -

Regaining Livelihoods for Pastoralist and Nomadic Communities in Sudan

REGAINING LIVELIHOODS FOR PASTORALIST AND NOMADIC COMMUNITIES IN SUDAN West Kordofan State has been affected by the continuing war in South Kordofan, the Darfur conflict and the civil war in South Sudan. The secession of South Sudan worsened the predicament of nomads in the area, as movements to the country were blocked. As a result, animals find themselves concentrated in a narrow area with limited resources during the dry season. Diseases that are preventable by vaccination are still considered major threats to animal production. Taking into account the lack of veterinary services in the area for a number of years, which has led to the spread of dangerous transboundary animal diseases, West Kordofan is considered a serious focus for the spread of diseases, undermining Sudan’s role as an important livestock-exporting agent in the region. In this context, the project provided an opportunity to build the capacity of both veterinarians and veterinary institutions. ©FAO/Albert Gonzalez Farran WHAT DID THE PROJECT DO? KEY FACTS Animal health services were upgraded and major animal Contribution diseases controlled through the provision of vaccination and USD 500 000 treatment services, training of veterinarians and community animal health workers and the promotion of disease Duration surveillance and veterinary diagnostic capabilities in West October 2014 – September 2017 Kordofan State. Resource Partners FAO IMPACT Partners The training of veterinarians and community animal health Federal Ministry of Livestock, State workers, as well as the capacity development of the El Fula Ministry of Animal Resources and Veterinary Laboratory through the provision of modern Fisheries for West Kordofan state equipment and tools, will directly contribute to the project’s Beneficiaries sustainability in West Kordofan State. -

South Sudan Emergency Sudan

South Sudan Emergency Sudan 13 January 2014 Highlights Violence in South Sudan continues, with further internal displacement and refugee movements to neighbouring countries, including Sudan Reports of nearly 10,000 new arrivals in Sudan, including nomadic groups Some 64,000 newly arrived South Sudanese refugees in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda Government of Sudan, UNHCR and partners are carrying out assessments, providing assistance and increasing preparedness for more arrivals Population figures Since the outbreak of violence in South Sudan on 15 December 2013, 355,000 people have been forced to flee their homes and remain internally displaced within South Sudan, with 69,000 sheltering in UNMISS bases. The latest figures for newly arrived South Sudanese refugees in neighbouring countries are as follows: - some 39,000 in Uganda; - 18,616 in Ethiopia; - 6,778 in Kenya; and - some 10,000 in Sudan (including nomadic groups), of whom 1,371 individuals have been confirmed by the Government of Sudan as being refugees. In Sudan, there are confirmed (but in many cases unverified) reports of new arrivals in the following areas: South Kordofan State According to the Government Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), 979 people have arrived from Malakal and Kaka in Upper Nile State to Abu Jubaiha locality, South Kordofan, including 517 individuals in Qurayd village and 450 individuals in Judayd village, approximately 40km south of Abu Jubaiha town. In Talodi locality, 2,574 individuals have arrived in El Liri, approximately 60km north of the border with Upper Nile State. The majority are from a nomadic population affected by the fighting in the Unity and Upper Nile States, and many of them have been assessed by local authorities as having urgent humanitarian needs. -

Sdn Lc Glpm A1l 20200712 Pdf.Pdf

20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E 32°30'0"E 35°0'0"E 37°30'0"E 40°0'0"E Marsa Oseif / HalaIb g! 0 n 2 a 0 El Wadah d EGYPT ! 2 N " u 0 ' y 0 l S 3 ° u 2 2 J Sararat Wadi Serimta Halfa/Aswan ! 2 1 g : SAUDI ARABIA LIBYA o Wad!i Halfa Al Uwaynat p MA'TAN AL-SARRA Marsa Oseif !h!( ! a g! !Bi'r Saratri M Major g Owens' n !Tomb i n !Dal n !Bi'r Liaumet a R l !Kosha P E s D c Sulb i ! ! t Wawa s i S g Delgo ! Musayab N RED SEA ! " 0 o ' E 0 ° L 0 2 l Taqab Kabodi Port Sudan A a ! ! r Abu Hamad * !(Port Sudan e h Marawarti !( k !(o @" ! !h ! n NORTHERN !Rubatab e Dongola G !( Suakin Wahat An Nukh o !( ! Dongola !h Habnab! Marsa ! Sinkat !Shaikh Sad !Hamdab !Shebatot !K!arima Marawi! Nuri !Tonak !Letti Basin Merowe o ! !Haya El Arian Mahattat !Maadam o Kerat ! !Sanda El Debba !Berber !Qanatti !Adarot NILE Atbara !Zibbelkelb Atbara !( o N " !(Ed Damer 0 ' 0 3 ° 7 1 !Umm Mineqla !Talgwoli ! Saloma Ungwatiri ! !Sawarat !El Hosh El Bqedab !( ! !Umm Guweira NORTH DARFUR Shendi !Shebergeid !El Khamesab Debbat Umm !El Husein KHARTOUM CHAD SUDAN ! Abu Halima KASSALA Khartoum * ERITREA Sutra !. ! El Kabra k o @ Sereif ! " ! ! Awadat o !( Furawiya * Angash ! ! } @ ! Muzbat " (!o Kassala Uru ! ! New Halfa Gurbura Jabalaulia ! o Mansi Karnoi ! N Malha " ! Malha ! 0 Umm Baru Gima ' !Tina Kiri-kir ! ! ! Um Haraz 0 ! ° ! 5 Miski Um El Helif NORTH AL GEZIRA 1 Mahareik ! Sigiba o Diyori ! Ana Bagi ! ! ! Anka KORDOFAN ! Hili Zedig ! ! ! Birmaza Madu ! Bakuri ! Kurbia Disa Umm Duwana! GEDAREF ! Buly! Sodari El Furei !Umm Daymayn At Turah Wad Medani!