South Kordofan and Blue Nile Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

Sudan Food Security Outlook Report

SUDAN Food Security Outlook February to September 2019 Deteriorating macroeconomic conditions to drive high levels of acute food insecurity in 2019 KEY MESSAGES • Food security has seasonally improved with increased cereal Current food security outcomes, February 2019 availability following the November to February harvest. However, the macroeconomic situation remains very poor and is expected to further deteriorate throughout the projection period, and this will drive continued extremely high food and non-food prices. The negative impacts of high food prices will be somewhat mitigated by the fact that livestock prices and wage labor are also increasing, though overall purchasing power will remain below average. A higher number of households than is typical will face Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse outcomes through September. • Between June and September, the lean season in Sudan, Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected in parts of Red Sea, Kassala, Al Gadarif, Blue Nile, West Kordofan, North Kordofan, South Kordofan, and Greater Darfur. Of highest concern are the IDPs in SPLM-N controlled areas of South Kordofan and SPLA-AW controlled areas of Jebel Marra, who have been inaccessible for both assessments and food assistance deliveries. IDPs in these areas are expected to be in Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC-compatible analysis follows Emergency (IPC Phase 4) during the August-September peak key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national of the lean season. food security partners. • The June to September 2019 rainy season is forecasted to be above average. This is anticipated to lead to flooding in mid-2019 and increase the prevalence of waterborne disease. -

Sudan's Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile Africa Report N°204 | 18 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Sudan in Miniature ....................................................................................................... 3 A. Old-Timers Versus Newcomers ................................................................................. 3 B. A History of Land Grabbing and Exploitation .......................................................... 5 C. Twenty Years of War in Blue Nile (1985-2005) ........................................................ 7 III. Failure of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ............................................................. 9 A. The Only State with an Opposition Governor (2007-2011) ...................................... 9 B. The 2010 Disputed Elections ..................................................................................... 9 C. Failed Popular Consultations ................................................................................... -

SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013

SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013 FEWS NET FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does Washington not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for [email protected] International Development or the United States Government. www.fews.net SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 4 Summary of Household Economy Approach Methodology ................................................................................... 5 The Household Economy Assessment in Sudan ..................................................................................................... 6 North Kordofan State Livelihood Profiling .............................................................................................................. 7 Overview of Rural Livelihoods in North Kordofan .................................................................................................. 8 Zone 1: Central Rainfed Millet and Sesame Agropastoral Zone (SD14) ............................................................... 10 Zone 2: Western Agropastoral Millet Zone (SD13) .............................................................................................. -

Anatomy of the Nile Following the Twists and Turns of the World's Longest River

VideoMedia Spotlight Anatomy of the Nile Following the twists and turns of the world's longest river For the complete video with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.org/media/anatomy-nile/ Funder The Nile River has provided fertile land, transportation, food, and freshwater to Egypt for more than 5,000 years. Today, 95% of Egypt’s population continues to live along its banks. Where does the Nile begin? Where does it end? Watch this video, from Nat Geo WILD’s “Destination Wild” series, to find out. For an even deeper look at the Nile, use our vocabulary list and explore our “geo-tour” of the Nile to understand the geography of the river and answer the questions in the Questions tab. Questions Where is the source, or headwaters, of the Nile River? The streams of Rwanda’s Nyungwe Forest are probably the most remote sources of the Nile. The snow-capped peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains are another one of the remote sources of the Nile. The Rwenzori Mountains, sometimes nicknamed the “Mountains of the Moon,” straddle the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. Many geographers also consider Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, to be a source of the Nile. The most significant outflow from Lake Victoria, winding northward through Uganda, is called the “Victoria Nile.” Can you find a waterfall on the Nile River? As it twists more than 6,500 kilometers (4,200 miles) through Africa, the Nile has dozens of small and large waterfalls. The most significant waterfall on the Nile is probably Murchison Falls, Uganda. -

Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. Payne Museum of Zoology The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN May 26, 1982 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. -

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021

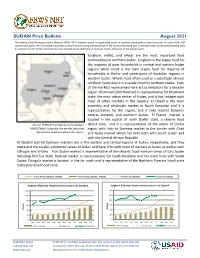

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, millet, and wheat are the most important food commodities in northern Sudan. Sorghum is the staple food for the majority of poor households in central and eastern Sudan regions while millet is the main staple food for majority of households in Darfur and some parts of Kordofan regions in western Sudan. Wheat most often used as a substitute all over northern Sudan but it is a staple food for northern states. Each of the markets represented here act as indicators for a broader region. Khartoum (Om Durman) is representative for Khartoum state, the main urban center of Sudan, and it has linkages with most of other markets in the country. El Obeid is the main assembly and wholesale market in North Kordofan and it is representative for the region, and it links market between central, western, and southern Sudan. El Fasher market is located in the capital of north Darfur state, a chronic food Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges deficit area, and it is representative of the entire of Darfur FAMIS/FMoA, Sudan for the market data and region with links to Geneina market in the border with Chad information used to produce this report. -

Amir Warns Against Oil Dependence, Terrorism

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2014 MUHARRAM 5, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Amir on Bahrain Macy’s heads Anelka makes brotherly bans main overseas with nightmarish visit to opposition branch in comeback Saudi Arabia3 group 7 Abu21 Dhabi in19 India Amir warns against oil Max 33º Min 21º dependence, terrorism High Tide 01:50 & 16:10 Low Tide PM calls to ‘tighten belts’ Speaker blasts opposition 09:25 & 21:25 40 PAGES NO: 16326 150 FILS • from the editor’s desk It’s time to get to work By Abd Al-Rahman Al-Alyan [email protected] is Highness the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah opened the 14th Hsession of Kuwait’s National Assembly yes- terday, urging lawmakers and the government to control spending and diversify Kuwait’s economy in the face of falling oil prices. “Here again, we are witnessing another cycle of sliding oil prices as a result of economic and politi- cal factors hitting the global economy, which is negatively affecting the national economy,” the KUWAIT: (From left) HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah, HH the Prime Minister Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah and Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanem attend the opening session of the new parliamentary term yesterday. — Photos by Yasser Al-Zayyat and KUNA Amir said. “I call on you, government and Assembly, to shoulder your national responsibility to issue the required legislation and decisions to By B Izzak safeguard our oil and fiscal wealth which is not for KUWAIT: His Highness the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- us alone but also for our future generations,” Ahmad Al-Sabah yesterday opened the new parliamen- Sheikh Sabah said. -

A Brief Description of the Nobiin Language and History by Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society)

A brief description of the Nobiin language and history By Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society) Nobiin language Nobiin (also called Mahas-Fadichcha) is a Nile-Nubian language (North Eastern Sudanic, Nilo-Saharan) descendent from Old Nubian, spoken along the Nile in northern Sudan and southern Egypt and by thousands of refugees in Europe and the US. Nobiin is classified as a member of the Nubian language family along with Kenzi/Dongolese in upper Nubia, Meidob in North Darfur, Birgid in Central and South Darfur, and the Hill Nubian languages in Southern Kordofan. Figure 1. The Nubian Family (Bechhaus 2011:15) Central Nubian Western Northern Nubian Nubian ▪ Nobiin ▪ Meidob ▪ Old Nubian Birgid Hill Nubians Kenzi/ Donglese In the 1960's, large numbers of Nobiin speakers were forcibly displaced away from their historical land by the Nile Rivers in both Egypt and Sudan due to the construction of the High Dam near Aswan. Prior to that forcible displacement, Nobiin was primarily spoken in the region between the first cataract of the Nile in southern Egypt, to Kerma, in the north of Sudan. The following map of southern Egypt and Sudan encompasses the areas in which Nobiin speakers have historically resided (from Thelwall & Schadeberg, 1983: 228). Nubia Nubia is the land of the ancient African civilization. It is located in southern Egypt along the Nile River banks and extends into the land that is known as “Sudan”. The region Nubia had experienced writing since a long time ago. During the ancient period of the Kingdoms of Kush, 1 | P a g e the Kushite/Nubians used the hieroglyphic writing system. -

Sudan: West Kordofan - Who Does What Where (3Ws) 1 April 2018 Jebrat El Sheikh Sodari

Sudan: West Kordofan - Who Does What Where (3Ws) 1 April 2018 Jebrat El Sheikh Sodari 2(UN/IOs) Organizations per locality / per sector NORTH KORDOFAN (INGOs) El Kuma 2 No. of organizations per sector: < 5 5 - 10 11 - 20 > 20 No data Sodari 8(NNGOs) 12 Localities Sectors Level of needs O per locality Total number of organizations SRCS IOM, SRCS SRCS SRCS IOM, SOS Sahel, SRCS Bara D Low Map legend A No. of organizations B Medium A State capital Umm Keddada per locality High Primary towns Total El Nehoud ABU Z Primary/paved road < 5 Acute Locality boundary 5 - 10 - 1 2 1 - 1 - - 3 - 3 Umm Keddada KalimendoState Boundary El Obeid 11 - 20 Undetermined Boundary > 20 WEST No data SRCS SRCS SRCS GAH SRCS Badya, SOS Sahel Wad Banda D SRCS KORDOFAN Shiekan GLA Abu Zabad Wad Banda El Nehoud U NORTH Abu Zabad En Nehoud Um Rawaba Localities Sectors DARFUR YEI -M Total Ghubaysh B Al Sunut A - 1 1 1 1 1 2 - 1 - 4 El Taweisha Al Qoz SRCS SRCS SRCS SRCS SRCS El Salam Ghubaysh Babanusa Lagawa IOM IOM Al Sunut Rashad T Ailliet Dilling Total Ghubaysh Abyei - Muglad KHOWAI AL Dalami Abu Karinka Habila Keilak - 1 1 1 - 1 - - 1 - 1 El Fula SUNU L Ed Daein A Total SOUTH - - 1 - - - - - 1 - 1 Adila KORDOFAN Um Heitan El Salam SRCS SRCS SRCS SC-S SRCS SRCS Heiban A Assalaya I Ed Daein EAST Babanussa Lagawa Reif Ashargi SRCS SRCS SRCS SC-S SRCS SOS Sahel SECS, Y SRCS Y Babanusa A DARFUR Heiban D UN /IOs & INGOs staff no. -

Role of Peace and Stability on Nomadic Animal Movements in South Kordofan

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies Role of peace and stability on nomadic animal movements in south kordofan Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. (on peace & conflicts studies) دور اﻷﻣﻦ اﻹﺳﺘﻘﺮار ﻋﻠﻰ ﺗﺤﺮﻛﺎت ﺣﯿﻮاﻧﺎت اﻟﺮﺣﻞ ﻓﻲ ﺟﻨﻮب ﻛﺮدﻓﺎن By: Abdel Aziz Abdalla Nour Eldin BSc. Agric. (Alex) Egypt June (1984) M. Sc (Animal Production Institute) University of Khartoum Sep. (1988) Supervision : Prof: Elhaj Abba (May 2015) اﻵﯾﺔ ﺑﺳم اﷲ اﻟرﺣﻣن اﻟرﺣﯾم } { 41 I Dedication This thesis is dedicated to soul of my mother, my father and my family for continuous support and encouragement II Acknowledgment I am gratefully indebted my supervisor Dr. Elhaj Abba for his keen interest in this study, his unfailing help and invaluable achieve during this work. Sincere gratitude also extended to my co-supervisor Dr. Salah Said Ahmed for his patient and encouragement throughout this work. Also thank extended to the following: Ustaz Lobna Hassan (um Maaz) for her constatnt encouragement, moral help, and advice throughout this work. Thanks to my extend family (brothers, sisters, unclose..) Finally, I want to thank my family for their constant encouragement, kind help, patient and support that help me to achieve this study. III Abstract The aim of this study is to focus on the movement of animals in its Southward and Northward tracks and the effect of such movement on tribal conflicts in this area and current resulting effect on the movement as well as the future effect, socially, economically, politically and the effect of the same movement on peace, stability and development in state along with method of treatment, provision of suggesting of the necessary solutions, determining the real effects of conflicts and the reasons leading to conflict. -

A List of the Birds of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Bawd on the Collections of Mr

416 Messrs. Sclater and Mackworth-Praed on [Ibis, XXII1.-A List of the Birds of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, bawd on the Collections of Mr. A. L. Butler, Mr. -4. Chapman and Capt. H. Lynes, R.N., and Mujor Cuthbcrt Christy, R.A.M.C. (T.F.). Part I. CORVIDX- FBINGILLIDB. By W. L. SCLATEB,M.B.O.U., and C. MACKWOBTH-PBAED, M.B.O.U. (Plate IX.) INTBODUCTION. UP to quite recently the great collection of Birds in the Natural History Museum’ has been singularly deficient in material from the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. This has recently been remedied by the donation of Mr. Butler of the large collection made by hini during a long residence in that country. Mr. Butler was appointed Superintendent of Game Pre- eervatiori to the Sudan Government iii 1901, and retained that post uiitil he retired in 1915. During those yearn he made good use of his opportunities of collecting birds throughout the Sudan, and the collection presented to the Museum consists of over 3100 beautifully prepared skim During his residence in the Sudau he published iu ‘ The Ibis ’ a series of four ‘‘ Contributions to the Ornithology of the Sudan ” between the years 1905 and 1909, in which he described the habits and in many cases unravelled the taxonomy of many of the species he had met with, and these papers are all referred to in the present list. We are much indebted to hiiir for help in drawing up this paper and for notes of the occurrence of several species in the Sudan not contained in the collection presented to the Museum.