Cultural Transmission and Semantic Change of Ceramic Forms in Grave Goods of Hellenistic Etruria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mysteries of the Baratti Amphora

ISSN: 2687-8402 DOI: 10.33552/OAJAA.2019.01.000512 Open Access Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Article Copyright © All rights are reserved by Vincenzo Palleschi The Mysteries of the Baratti Amphora Claudio Arias1, Stefano Pagnotta2, Beatrice Campanella2, Francesco Poggialini2, Stefano Legnaioli2, Vincenzo Palleschi2* and Cinzia Murolo3 1Retired Professor of Archaeometry, University of Pisa, Italy 2Institute of Chemistry of Organometallic Compounds, CNR Research Area, Pisa, Italy 3Curator at Museo Archeologico del Territorio di Populonia, Piazza Cittadella, Piombino, Italy *Corresponding author: Vincenzo Palleschi, Institute of Chemistry of Organometallic Received Date: April 22, 2019 Compounds, CNR Research Area, Pisa, Italy. Published Date: May 08, 2019 Abstract Since its discovery, very few certain information has been drawn about its history, provenience and destination. Previous archaeometric studies and the iconographyThe Baratti ofAmphora the vase is might a magnificent suggest asilver late antique vase, casually realization, recovered possibly in 1968 in an from Oriental the seaworkshop in front (Antioch). of the Baratti A recent harbor, study, in Southern performed Tuscany. by the National Research Council of Pisa in collaboration with the Populonia Territory Archaeological Museum, in Piombino, has led to a detailed study of the Amphora, both from a morphological point of view through the photogrammetric reconstruction of a high-resolution 3D model, and from the point of view of the analysis of the constituent -

The Oceanographic Achievements of Vito Volterra in Italy and Abroad1

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies- Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 251-266 The Oceanographic Achievements of Vito Volterra in Italy and Abroad1 By Sandra Linguerri The aim of this paper is to introduce Vito Volterra’s activity as a policy maker in the field of oceanography. In 1908, he was the promoter of the Thalassographic Committee (then in 1910 Royal Italian Thalassographic Committee), a national endeavor for marine research vis-à-vis the industrial world of fisheries, which soon internationalized. Abroad it was affiliated with the International Commission for the Scientific Exploration of the Mediterranean Sea, led by Albert I, Prince of Monaco (1919-1922) and then by Vito Volterra himself (1923-1928).1 Keywords: History, International Commission for the Scientific Exploration of the Mediterranean Sea, Oceanography, Royal Italian Thalassographic Committee, Vito Volterra. Vito Volterra and the Royal Italian Thalassographic Committee Vito Volterra (1860-1940) (Goodstein 2007, Guerraggio and Paoloni 2013, Simili and Paoloni 2008) is generally considered one of the greatest mathematicians of his time. His most important contributions were in functional analysis, mathematical ph‟ scientific activities, rather it will focus on his contribution to talassographic (or oceanographic) studies, and especially on the creation of the Royal Italian Talassographic Committee (Linguerri 2005, Ead 2014). In 1900, after teaching in Pisa and Turin, Volterra was offered a chair in mathematical physics at the University of Rome, where he was invited to give the inaugural lecture for the new academic year entitled Sui tentativi di applicazione delle matematiche alle scienze biologiche e sociali (On the attempts to apply mathematics to the biological and social sciences), which demonstrated his great interest in the application of mathematics to biological sciences and to economic research. -

Volterra Volterra, Known to the Ancient Etruscans As Velathri Or Vlathri and to the Romans As Volaterrae, Is a Town and a Comune in Tuscany

Volterra Volterra, known to the ancient Etruscans as Velathri or Vlathri and to the Romans as Volaterrae, is a town and a comune in Tuscany. The town was a Bronze Age settlement of the Proto-Villanovan culture, and an important Etruscan centre, one of the "twelve cities" of the Etruscan League. The site is believed to have been continuously inhabited as a city since at least the end of the 8th century BC. It became a municipium allied to Rome at the end of the 3rd century BC. The city was a bishop's residence in the 5th century, and its episcopal power was affirmed during the 12th century. With the decline of the episcopate and the discovery of local alum deposits, Volterra became a place of interest for the Republic of Florence, whose forces conquered it. Florentine rule was not always popular, and opposition occasionally broke into rebellions which were quelled by Florence. When the Republic of Florence fell in 1530, Volterra came under the control of the Medici family and subsequently its history followed that of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.4 The Roman Theatre The Main Sights 1. Roman Theatre of Volterra, 1st century BC, excavated in the 1950s; 2. Piazza dei Priori, the main square, a fine example of medieval Tuscan town squares; 3. Palazzo dei Priori, the town hall located on Piazza dei Priori, construction begun in 1208 and finished in 1257; 4. Pinacoteca e museo civico di Volterra (Art Gallery) in Palazzo Minucci-Solaini. Founded in 1905, the gallery consists mostly of works by Tuscan artists from the 14th to the 17th centuries. -

Etruscan Biophilia Viewed Through Magical Amber

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber Greta Rose Koshenina University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Koshenina, Greta Rose, "Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber" (2020). Honors Theses. 1432. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1432 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETRUSCAN BIOPHILIA VIEWED THROUGH MAGICAL AMBER by Greta Rose Koshenina A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2020 Approved by ___________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. John Samonds © 2020 Greta Rose Koshenina ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis with gratitude to my advisors in both America and Italy: to Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons who endured spotty skype meetings during my semester abroad and has been a tremendous help every step of the way, to Giampiero Bevagna who helped translate Italian books and articles and showed our archaeology class necropoleis of Etruria, and to Dr. Brooke Porter who helped me see my research through the eyes of a marine biologist. -

The Founding of the City

1 The Founding of the City 1. The environment of rome’s early hisTory Italy: A Geographically Fragmented Land italy is not a naturally unified land. It is a mosaic of different regions and sub-regions that through- out history have had difficulty communicating with each other. It lacks a large natural “center” the way, for instance, France and England have geographically coherent central homelands, or as Egypt or Mesopotamia had in antiquity. Symbolic of the way the ancients thought about Italy was the fact that for a good portion of their history, Romans did not think of the Po valley, today Italy’s most productive region, as part of Italy, and with good reason. The Po constituted what amounted to a separate country, being generally more in contact with continental Europe through the Brenner Pass than with peninsular Italy to the south where the Apennines impeded communications. The Romans called the Po valley Gallia Cisalpina—that is, “Gaul-on-this-side-of-the-alps.” (Gaul proper or modern france was Gallia Transalpina—“Gaul-on-the other side-of-the-alps”). it was an alien land inhabited by Gauls (Gaels—or, as we know them more commonly, Celts). Vestiges of this sense of regional diversity persist to the present. An active political movement currently seeks to detach northern Italy from the rest of the country, arguing that as the most developed and wealthiest part of italy, the north should not be forced to subsidize backward parts of southern Italy and Sicily. Other parts of Italy besides the Po valley are still difficult to reach from each other. -

A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 8 Article 4 2001 A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Magness, Jodi (2001) "A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite?," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Near EasTern EThnic ElemenT Among The ETruscan EliTe? by Jodi Magness INTRODUCTION:THEPROBLEMOFETRUSCANORIGINS 1 “Virtually all archaeologists now agree that the evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of the “indigenous” theory of Etruscan origins: the development of Etruscan culture has to be understood within an evolutionary sequence of social elaboration in Etruria.” 2 “The archaeological evidence now available shows no sign of any invasion, migra- Tion, or colonisaTion in The eighTh cenTury... The formaTion of ETruscan civilisaTion occurred in ITaly by a gradual process, The final sTages of which can be documenTed in The archaeo- logical record from The ninTh To The sevenTh cenTuries BC... For This reason The problem of ETruscan origins is nowadays (righTly) relegaTed To a fooTnoTe in scholarly accounTs.” 3 he origins of the Etruscans have been the subject of debate since classical antiqui- Tty. There have traditionally been three schools of thought (or “models” or “the- ories”) regarding Etruscan origins, based on a combination of textual, archaeo- logical, and linguistic evidence.4 According to the first school of thought, the Etruscans (or Tyrrhenians = Tyrsenoi, Tyrrhenoi) originated in the eastern Mediterranean. -

Social Mobility in Etruria Gérard Capdeville

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 9 Article 15 2002 Social Mobility in Etruria Gérard Capdeville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Capdeville, Gérard (2002) "Social Mobility in Etruria," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SociaL MobiLity iN Etruria by Gérard Capdeville H(astia) . Ecnatnei . Atiuce . lautnic ([ CIE , 3088 =] TLE , 550 = Cl 1.1568) y “social Mobility” I MeaN here a chaNge of social class, which is Not easy to dis - cerN iN Etruria because we do Not have Much geNeral iNforMatioN oN the struc - Bture of EtruscaN society. The Most iMportaNt chaNge, aNd the Most obvious, is the traNsitioN froM servile to free status, heNce the iMportaNce of freedMeN for our subject. The word for “freedMaN” is well kNowN, as we have circa 175 iNscriptioNs: it is lautuni, lautni (rec. lavtni ), feM. lautni a, lautnita (rec. lavtnita ). Its MeaNiNg is attested by two biliNgual Etrusco-LatiN iNscriptioNs ( CIE , 1288 ClusiuM; 3692 Perugia), which testify to the equivaleNce of lautNi to the LatiN libertus. EquivaleNce does Not MeaN ideNtity of status, especially duriNg the iNdepeNdeNt cities period. At least two questioNs arise. What is the relatioNship betweeN the lautni aNd his forMer Master? What is the positioN of the lautni as regards citizeNship? The oNoMastic, for which we have a very rich corpus of epitaphs, provides us with part of the aNswer. -

June 18 to 27, 2020 a Program of the Stanford Alumni Association

ANCIENT ISLANDS AND CITIES June 18 to 27, 2020 a program of the stanford alumni association What could possibly be more exciting than skimming across the blue Mediterranean at full sail on a three-masted ship, en route to an ancient port or a storied island you’ve always dreamed of visiting? Add to this the opportunity to hear intriguing lectures by Stanford professor Marsh McCall, who will illuminate the history behind these picturesque islands and seaside ruins. Aboard the newly refurbished Le Ponant, we’ll visit seven ports of call in France and Italy. Learn about ancient cultures, stroll through quaint medieval towns, admire modern art and architecture, and taste the fabulous food and wines of this prolific region. Best of all, enjoy all this while relaxing in the summer sunshine. We hope you’ll join us on this modern odyssey. BRETT S. THOMPSON, ’83, DIRECTOR, STANFORD TRAVEL/STUDY VOLTERRA, ITALY Highlights WALK in the footsteps of ADMIRE the works of EXPLORE the spectacular STROLL through a the ancient Etruscans of several renowned 20th- coastal cliffs and hiking trails nuraghe, a Bronze Age Volterra, wandering through century artists in St. Paul of the Cinque Terre, five settlement complete with archaeological ruins while de Vence on the French pastel-hued fishing villages intact megalithic stone learning about the early Riviera. linked by footpaths. towers, on Sardinia. civilization in Italy. COVER: CAMOGLIA, ITALY Faculty Leader Classics professor MARSH MCCALL decided he would become a teacher when he was in the third grade and went on to fulfill that desire, introducing legions of university students to the study of classics during a decades-long professorship at Stanford. -

The Roman Settlement of Poggio Del Molino: the Late Republican Fort and the Early Imperial Farm

The Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179) ● Published by the Associazione Internazionale di Archeologia Classica ● Palazzo Altemps, Via Sant'Appolinare 8 – 00186 Roma ● Tel. / Fax: ++39.06.67.98.798 ● http://www.aiac.org; http://www.fastionline.org The Roman Settlement of Poggio del Molino: the Late Republican Fort and the Early Imperial Farm Stefano Genovesi – Carolina Megale The Roman Settlement of Poggio del Molino, located in the territory controlled by the city of Populonia (Piombino, Livorno), has long drawn the interest of archaeologists. Excavations conducted by the University of Florence were interrupted for twenty years and eventually resumed in 2008. The new research project has provided evidence for the site’s architectural evolution, revealing different construction stages and uses of spaces during a time of intense environmental and political change. Such data confirm the strategic importance of Poggio del Molino throughout a very long period of Roman history, from the Late Republic to the end of the Empire– mid 2nd century BCE-beginning of 5th century CE. The new research project is endorsed and supported by public institutions (Municipality of Piombino and University of Florence) as well as private national and international institutions (Cultur- al Association Past in Progress, Earthwatch Institute, University of Arizona, Hofstra University, Union College, Foundation RavennAntica) which are involved in field surveys, post-excavation studies and initiatives concerning the site’s enhancement. This paper focuses on the oldest stage of the site’s history, the Late Republican Fort, and on the second stage, the farm with fish sauce production. 1 - The Late Republican Fort of Poggio del Molino. -

The Ancient People of Italy Before the Rise of Rome, Italy Was a Patchwork

The Ancient People of Italy Before the rise of Rome, Italy was a patchwork of different cultures. Eventually they were all subsumed into Roman culture, but the cultural uniformity of Roman Italy erased what had once been a vast array of different peoples, cultures, languages, and civilizations. All these cultures existed before the Roman conquest of the Italian Peninsula, and unfortunately we know little about any of them before they caught the attention of Greek and Roman historians. Aside from a few inscriptions, most of what we know about the native people of Italy comes from Greek and Roman sources. Still, this information, combined with archaeological and linguistic information, gives us some idea about the peoples that once populated the Italian Peninsula. Italy was not isolated from the outside world, and neighboring people had much impact on its population. There were several foreign invasions of Italy during the period leading up to the Roman conquest that had important effects on the people of Italy. First there was the invasion of Alexander I of Epirus in 334 BC, which was followed by that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. Hannibal of Carthage invaded Italy during the Second Punic War (218–203 BC) with the express purpose of convincing Rome’s allies to abandon her. After the war, Rome rearranged its relations with many of the native people of Italy, much influenced by which peoples had remained loyal and which had supported their Carthaginian enemies. The sides different peoples took in these wars had major impacts on their destinies. In 91 BC, many of the peoples of Italy rebelled against Rome in the Social War. -

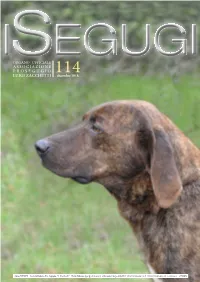

Segugio Maremmano 4

ORGANO UFFICIALE ASSOCIAZIONE PROSEGUGIO LUIGI ZACCHETTI 114dicembre 2018 Anno XXXVII - Società Italiana Pro Segugio “L. Zacchetti” - Poste Italiane Spa Spedizione in abbonamento postale D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n.46) art.1 comma 1 – CN/RN SOMMARIO Convovazione Assemblea Generale Soci 1 Editoriale 2 Ufficializzato il riconoscimento FCI del Segugio Maremmano 4 Un iter lungo, ma obiettivo raggiunto 8 Sul Grappa per Campionato Italiano SIPS 2018 12 ORGANO UFFICIALE A Chieti per il Campionato Italiano SIPS su Cinghiale 18 ASSOCIAZIONE PROSEGUGIO LUIGI ZACCHETTI 114dicembre 2018 Convocazione Assemblea Presidenti di Sezione 24 Anno XXXVII Calendario 1º semestre 2019 25 Direttore Responsabile Vincenzo Ferrara Monumento a Gildo Fioravanti 33 Comitato di Redazione Palmiro Clerici, Massimiliano Cornoldi, Trofeo Toscana d’Eccellenza 2018 36 Bruno Mugnaini, Simona Pelliccia Archivio fotografico Segugio dell’Appennino, facciamo il punto 38 SIPS “Luigi Zacchetti” Proprietà ed editore 8º Trofeo e 8ª Coppa Beretta 40 SIPS “Luigi Zacchetti” Casalpusterlengo (Lodi) Progetto grafico Al cinofilo la lepre serve anche viva 42 studioDODdesign - Massa Lombarda Stampa Finale Mari e Monti, inter-regionale del Nord Italia su Cinghiale 46 Tipografia Lineastampa snc - Rimini Pubblicità “Ripensare le quattro fasi” 48 Segreteria SIPS Tel. 0377 802414 - Fax 0377 802234 www.prosegugio.it Dalle sezioni 50 E- mail: [email protected] Spedizione Autorizzazione del Tribunale CONVOCAZIONE DELL’ASSEMBLEA GENERALE DEI SOCI di Crema n. 57/86 Ai sensi dell’art. 13 -

Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century Bce

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND LITERARY ETRUSCANS: CONSTRUCTIONS OF ETRUSCAN IDENTITY IN THE FIRST CENTURY BCE John B. Beeby A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: James B. Rives Jennifer Gates-Foster Luca Grillo Carrie Murray James O’Hara © 2019 John B. Beeby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT John B. Beeby: Archaeological and Literary Etruscans: Constructions of Etruscan Identity in the First Century BCE (Under the direction of James B. Rives) This dissertation examines the construction and negotiation of Etruscan ethnic identity in the first century BCE using both archaeological and literary evidence. Earlier scholars maintained that the first century BCE witnessed the final decline of Etruscan civilization, the demise of their language, the end of Etruscan history, and the disappearance of true Etruscan identity. They saw these changes as the result of Romanization, a one-sided and therefore simple process. This dissertation shows that the changes occurring in Etruria during the first century BCE were instead complex and non-linear. Detailed analyses of both literary and archaeological evidence for Etruscans in the first century BCE show that there was a lively, ongoing discourse between and among Etruscans and non-Etruscans about the place of Etruscans in ancient society. My method musters evidence from Late Etruscan family tombs of Perugia, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Books 1-5 of Livy’s history. Chapter 1 introduces the topic of ethnicity in general and as it relates specifically to the study of material remains and literary criticism.