Creating Thunder: the Western Rain- Making Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Narrative Volume 1

History into fiction: the metamorphoses of the Mithras myths ROGER BECK Toronto Dedicated to Reinhold Merkelbach, whose explorations of ancient narra- tive and the mystery cults have always seemed to me profoundly well oriented, even when I would not follow the same path in detail. This article is neither about a particular ancient novel nor about the genre of the ancient novel in general. But it is about story-telling in the ancient world, and about the metamorphosis which stories undergo when they pass through the crucible of religious invention. Its subject, then, is narrative fiction — narrative fiction as the construction of sacred myth and of myth’s dramatic counterpart, ritual performance. The fictions I shall explore are the myths and rituals of the Mithras cult. Some of these fictions, I shall argue, are elaborations of events and fantasies of the Neronian age: on the one hand, events in both Italy and the orient cen- tred on the visit of Tiridates of Armenia to Rome in 66; on the other hand, the heliomania of the times, a solar enthusiasm focused on, and in some measure orchestrated by, the emperor himself. What I am not offering is an explanation of Mithraism and its origins. In the first place, our subject is story and the metamorphosis of story, not relig- ion. In the second place, I would not presume to ‘explain’ Mithraism, or any other religion for that matter, by Euhemeristic reduction to a set of historical or pseudo-historical antecedents. In speaking of the ‘invention’ of Mithraism and of its ‘fictions’, moreover, I intend no disrespect. -

Examining the Transference Between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J

\ The Sword and the Cross: Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J. Decker III Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Manwell Ph. D .. Kalamazoo College Co-Chair of Classics Department I - A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degr~e of Bachelor of ~rts at - - Kalamazoo College. 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................... ~ .... : ......................................................ii I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs ............................... .1-21 II. Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity ............... ~ .. 23-38 III. Appendix .......................· ............................................................. 39 Bibliography .................... ·................................................................. 40-44 / 11 Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to my loving parents who made it possible to attend Kalamazoo College and allow me to further my studies in Classics. Without their financial and emotional support I would not have been able to complete this Senior Independent Project (SIP). Love you Mom and Dad! I am also deepl_y thankful to the Todd family and their generous grant, the Todd Memorial Classics Study Abroad Grant, which allowed me to travel to Italy and gain the inspiration for the topic of my SIP. I would like to express aspecial thanks to my SIP advisor Prof. Manwell, for putting up with all my procrastination and my challenging writing. I hope you didn't spend to many nights up late editing my drafts. Without all of you none of this would have been possible. Thank you very much. 1 I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs In the spring of 2011 an American atheist group put up a billboard in downtown New York City which read: "Born of a virgin on December 25th, known to his 12 disciples as "the Son of God, and resurrected three days after his death, we wish a Happy Birthday to Mithras, the mythical Persian god imagined over 600 years before that other guy .. -

History Religion Tokarev.Pdf

STUDENT'S LIBRARY Sergei Tokarev History of RELIGION PROGRESS PUBLISHERS MOSCOW Translated from the Russian by Paula Garb Editorial Board of the Series: F.M. Volkov (Managing Editor), Ye.F. Gubsky (Deputy Managing Editor), V.G. Afanasyev, Taufik Ibrahim, Zafar Imam, I.S. Kon, I.M. Krivoguz, A.V. Petrovsky, Yu.N. Popov, Munis Reza, N.V. Romanovsky, V.A. Tumanov, A.G. Zdravomyslov, V.D. Zotov. BHEJIHOTEKA CTYflEHTA C. T oK apeB HCTOPMH PEJIWrHM Ha ammiucKOM H3biKe © IIOJIHTH3AaT, 1986 © Progress Publishers 1989 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 0400000000-438 g 9 014(01)-89 ISBN 5-01-001097-6 Contents TRIBAL CULTS Chapter One ARCHEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS ................................ 9 1. Paleolithic S ite s ........................................................................ 9 2. Neolithic S ites.............................................................................. 13 3. Religion in the Early Bronze and Iron Age .... 16 Chapter Two RELIGION OF THE AUSTRALIANS AND TASMANIANS............................ 18 1. The A u stralian s........................................................................ 18 2. The T asm anians........................................................................ 33 Chapter Three RELIGION IN OCEANIA ........................................................................ 35 1. The Papuans and M elanesians.................................................. 36 2. The P olynesians........................................................................ 42 Chapter Four -

Native American Myth, Memory and History Seminar What Does It Look

RSOC Native American Myth, Memory and History Seminar Religious Studies, Santa Clara University Fall T/TH 12:10 – 1:50 Kenna 306 Jean Molesky-Poz [email protected] Off. Hrs. T/Th 9:45 – 10:45; and by apt. Kenna 307 Native American Myth, Memory and History Seminar “I’ll tell you something about stories, he said. They aren’t just entertainment. Don’t be fooled. They are all we have, you see, all we have to fight off illness and death.” Ceremony, Leslie Silko, 2. What does it look like when mythology, history and the future intersect? Course Description: This seminar examines creation accounts of native peoples, exploring Earth/sky relations, the reciprocity between the human community, the Sacred and the rest of creation. Focus on the stories of the Kiowa (Plains), the K’iche-Maya Popul Vuj (Central America), northern and southern Native California, and the Southwest. We consider how memories of these stories have informed historical and contemporary lives, and how native peoples today reclaim these accounts as transformed continuities, as they resist environmental devastation, claim sacred sites and practices, work determined to protect land rights and our common future. In the first unit, we compare Native California, northern and southern peoples, how contemporary Native Californians are reclaiming their creation and migration stories, their sacred sites and rituals, to create a viable future. As Junipero Serra will be canonized in Fall, 2015, special attention will be given to the fact/fiction of the encounter between Native peoples and the Spanish in Alta California. In the second unit, we examine the creation stories of the Plain’s peoples – the Kiowa and the Lakota -- the relation of story to sacred geography, to peyote and sacred pipe rituals, and to ways contemporary Plains’ people engage in the stories to protect land and sacred sites (Medicine Wheels, Lodge of the Bear, and the tar pits of Canada). -

A Genocidal Legacy: a Case Study of Cultural Survival

A GENOCIDAL LEGACY: A CASE STUDY OF CULTURAL SURVIVAL IN NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Anthropology ____________ by Aimee L. VanHavermaat-Snyder Fall 2017 A GENOCIDAL LEGACY: A CASE STUDY OF CULTURAL SURVIVAL IN NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis by Aimee L. VanHavermaat-Snyder Fall 2017 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: _________________________________ Sharon Barrios, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ _________________________________ Guy Q. King, Ph.D. Antoinette Martinez, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Frank Bayham, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to begin by thanking the Bear River Band at Rohnerville Rancheria for their support of the Benbow Archaeological Project and this thesis. I would also like to thank Erika Cooper, THPO for the Bear River Band at Rohnerville Rancheria, Rick Fitzgerald of California State Parks, Kevin Dalton, and everyone involved with the Benbow Archaeological Project. A huge thanks goes to Greg Collins of California State Parks for leading this archaeological endeavor and for supporting this thesis work. Thank you to my thesis committee, Antoinette Martinez and Frank Bayham. Nette, your guidance and influence as an archaeologist, anthropologist, teacher, and friend have meant so much to me. The profound impact of your teaching career is immeasurable, and I count myself lucky to have studied and grown under your guidance. You have changed me and will forever be my example of a strong, brilliant, kind, and powerful woman. Frank, I have had so much fun working with you as your ISA, having you on my crew at Benbow, in class, on this thesis, and beyond! Dad, Mom (Lisa Pizza), and brother, I know how truly lucky I am to have such an amazing family. -

Supplemental Resources

Supplemental Resources By Beverly R. Ortiz, Ph.D. © 2015 East Bay Regional Park District • www.ebparks.org Supported in part by a grant from The Vinapa Foundation for Cross-Cultural Studies Ohlone Curriculum with Bay Miwok Content and Introduction to Delta Yokuts Supplemental Resources Table of Contents Teacher Resources Native American Versus American Indian ..................................................................... 1 Ohlone Curriculum American Indian Stereotypes .......................................................................................... 3 Miner’s Lettuce and Red Ants: The Evolution of a Story .............................................. 7 A Land of Many Villages and Tribes ............................................................................. 10 Other North American Indian Groups ............................................................................ 11 A Land of Many Languages ........................................................................................... 15 Sacred Places and Narratives .......................................................................................... 18 Generations of Knowledge: Sources ............................................................................... 22 Euro-American Interactions with Plants and Animals (1800s) .......................................... 23 Staple Foods: Acorns ........................................................................................................... 28 Other Plant Foods: Cultural Context .............................................................................. -

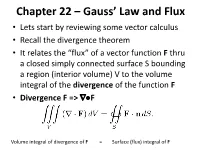

Chapter 22 – Gauss' Law and Flux

Chapter 22 – Gauss’ Law and Flux • Lets start by reviewing some vector calculus • Recall the divergence theorem • It relates the “flux” of a vector function F thru a closed simply connected surface S bounding a region (interior volume) V to the volume integral of the divergence of the function F • Divergence F => F Volume integral of divergence of F = Surface (flux) integral of F Mathematics vs Physics • There is NO Physics in the previous “divergence theorem” known as Gauss’ Law • It is purely mathematical and applies to ANY well behaved vector field F(x,y,z) Some History – Important to know • First “discovered” by Joseph Louis Lagrange 1762 • Then independently by Carl Friedrich Gauss 1813 • Then by George Green 1825 • Then by Mikhail Vasilievich Ostrogradsky 1831 • It is known as Gauss’ Theorem, Green’s Theorem and Ostrogradsky’s Theorem • In Physics it is known as Gauss’ “Law” in Electrostatics and in Gravity (both are inverse square “laws”) • It is also related to conservation of mass flow in fluids, hydrodynamics and aerodynamics • Can be written in integral or differential forms Integral vs Differential Forms • Integral Form • Differential Form (we have to add some Physics) • Example - If we want mass to be conserved in fluid flow – ie mass is neither created nor destroyed but can be removed or added or compressed or decompressed then we get • Conservation Laws Continuity Equations – Conservation Laws Conservation of mass in compressible fluid flow = fluid density, u = velocity vector Conservation of an incompressible fluid = -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa". -

A Reader in Comparative Indo-European Religion

2018 A READER IN COMPARATIVE INDO-EUROPEAN RELIGION Ranko Matasović Zagreb 2018 © This publication is intended primarily for the use of students of the University of Zagreb. It should not be copied or otherwise reproduced without a permission from the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................................................ Foreword............................................................................................................................... PART 1: Elements of the Proto-Indo-European religion...................................................... 1. Reconstruction of PIE religious vocabulary and phraseology................................... 2. Basic Religious terminology of PIE.......................................................................... 3. Elements of PIE mythology....................................................................................... PART II: A selection of texts Hittite....................................................................................................................................... Vedic........................................................................................................................................ Iranian....................................................................................................................................... Greek....................................................................................................................................... -

Origins of Hinduism: the Indus Vanev Cmlizauon

Hinduism Indian Religions Name ____________________ Origins of Hinduism: TheIndus vanev CMliZaUon i Hnduism. unlike most majorreligions, does not have a central figure upon whom it is founded. Rather, it is a complex faith with rootsstemming back fivethousand yearsto the people of the Indus Valley, now part of Pakistan. When the Aryan tribesof Persia invaded theIndus Valley around 1700 BCE, the groups' beliefsmerged and Hinduism beganto form. Most of what we know of the Indus people (also called Dravidians)comes fromarchaeological find ings. Artifacts and relics dating back as early as 2000BCE tell the story of a civilization flourishing with craftsmanship, agriculture, and religious life. As··we will see, manyof these earlypractices and beliefsstill shape Hinduism. For example, the Indus put greatimportance on cleanliness or ritual bathing. MohenjoDaro, one of the major Indus cities, contained a huge water tankfor public bathing. Today, many Hindu temples feature such tanks. Another lastinglegacy of Hinduism is foundin the abundanceof terra-cottafigurines unearthed in the Indus Valley. Popular amongthese small ceramicstatuettes were depictions of pregnant women, "mother goddesses." The fertility and strengthof the goddess and the rebirth andcontinuity she pro vides remaincentral to the Hindu faith. Ceramicseals also provideinsight into the Indus' religious beliefs. Among the most common design was that of the bull. It represented virility, or sexual force,which is still consideredsacred to the Hindus. Shiva, among the most revered Hindu gods, is associated with the bull. The Indus were an agriculturalpeople, growing crops and raising animals. Livingon the banks of the Indus River, dependent on its nourishment and renewal, there was deep reverencefor water. -

Diet and Identity Among the Ancestral Ohlone

DIET AND IDENTITY AMONG THE ANCESTRAL OHLONE: INTEGRATING STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS AND MORTUARY CONTEXT AT THE YUKISMA MOUND (CA-SCL-38) ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Anthropology ____________ by Karen Smith Gardner Spring 2013 DIET AND IDENTITY AMONG THE ANCESTRAL OHLONE: INTEGRATING STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS AND MORTUARY CONTEXT AT THE YUKISMA MOUND (CA-SCL-38) A Thesis by Karen Smith Gardner Spring 2013 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _________________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ _________________________________ Guy Q. King, Ph.D. Eric Bartelink, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Antoinette M. Martinez, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The process of completing this degree and writing this thesis has been a homecoming for me, returning me to the ideas and complexities of anthropology and to the rolling hills and valleys of Central California, where I grew up. First and foremost, I would like to thank Rosemary Cambra and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe for your interest and support of this project. I am humbled by your trust in giving me this access to your past. It has been my honor to glimpse the lives of your ancestors. My thesis committee has been tremendously supportive. To Dr. Eric Bartelink and Dr. Antoinette Martinez, thank you for your patience and encouragement. Between you, you have provided me with a wonderful breadth of knowledge. Eric, as a pioneer of stable isotope analysis in Central California you have introduced new potential to the interpretation of the prehistoric past here, and passed this enthusiasm along to your students. -

Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 370 605 IR 055 088 AUTHOR Brandt, Randal S.; Davis-Kimball, Jeannine TITLE Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians. Volume 3--General Bibliography. INSTITUTION California State Library, Sacramento.; California Univ., Berkeley. California Indian Library Collections. St'ONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. Office of Library Programs. REPORT NO ISBN-0-929722-78-7 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 251p.; For related documents, see ED 368 353-355 and IR 055 086-087. AVAILABLE FROMCalifornia State Library Foundation, 1225 8th Street, Suite 345, Sacramento, CA 95814 (softcover, ISBN-0-929722-79-5: $35 per volume, $95 for set of 3 volumes; hardcover, ISBN-0-929722-78-7: $140 for set of 3 volumes). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Films; *Library Collections; Maps; Photographs; Public Libraries; *Resource Materials; State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS *California; Unpublished Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third of a three-volume set made up of bibliographic citations to published texts, unpublished manuscripts, photographs, sound recordings, motion pictures, and maps concerning Native American tribal groups that inhabit, or have traditionally inhabited, northern and central California. This volume comprises the general bibliography, which contains over 3,600 entries encompassing all materials in the tribal bibliographies which make up the first two volumes, materials not specific to any one tribal group, and supplemental materials concerning southern California native peoples. (MES) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S.