Thunderbolts’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politsei Tabas Kuressaares Korteripeolt 15 Purjus Last Üks Nooruk Ähvardas Marientali De Patrullidega, Kuna Maja Seestpoolt Lukku,” Rääkis Sikk Su Alkoholi

“Ükskord Riigigümnaasium lindilõikamise ootel LK 2 • Kauneimad kodud: suur fotogalerii LK 6-8 nägin rada ainult läbi Taasiseseisvumis- prillidel päeval heiskame olevate riigilipu! väikeste pilude.” KUUEAASTANE Järgmine Saarte Hääl MOTOSPORTLANE ilmub laupäeval, 21.08 NIKLAS JOHANSON LK 4 Neljapäev, 19. august 2021 • Nr 135 (5389) • Hind 1,20 € VÄLJAKUTSELE KÕIK VABAD JÕUD: Politseil oli alust arvata, et tegemist tuleb suure hulga alkoholi tarvitanud noortega. Nii oligi. FOTOMONTAAŽ / LIINA ÕUN Politsei tabas Kuressaares korteripeolt 15 purjus last Üks nooruk ähvardas Marientali de patrullidega, kuna maja seestpoolt lukku,” rääkis Sikk su alkoholi. Aga oli ka neid, kes olid räägitud. Lugu ise oli Siku sõnul vägagi korterelamu kolmandal korrusel ukse ees oli kümmekond Marientali operatsioonist. jõudnud ära juua pudeli või rohkem.” õpetlik. Esmaspäeva pealelõuna ja õh- peetud peol aknast alla hüpata. jalgratast. Siiski õnnestus politseil Leiti ka sigarette ja e-sigaret. Siku tupoolik tunduvad olevat üsna süütu “Tuppa astudes oli tunda tugevat “Et oleks nende lastega ust lõhkumata korterisse sõnul võib arvata, et üht-teist jõudsid aeg, mil poleks nagu erilist põhjust las- alkoholilõhna,” ütleb politsei. seal jõudu tegeleda,” põh- pääseda ning üsna pea noored ka tualetipotist alla lasta. te tegemisi kontrollida, midagi taolist jendas Sikk, viidates, et oli saabus kohale ka korteri Tabatud noored viidi politseijaos- eeldaks pigem nädalavahetuselt. alust arvata, et tegemist tu- omanik. Pidutsejate vanus konda, koostati protokollid ning lapse- Tõenäoliselt mängis korterisse ko- Kadri Häng-Nuum, Raul Vinni leb suure hulga alkoholi tar- jäi vahemikku 13–17, ena- vanemad tulid võsukestele järele. gunemisel oma rolli vihmane ilm. [email protected] vitanud noortega. masti oli tegu 13–15-aastaste- Pealtnägijate sõnul käisid lapsevane- “Muidu oleks nad võib-olla kuskil Esmalt tabati trepikojast kaks ga. -

Ancient Narrative Volume 1

History into fiction: the metamorphoses of the Mithras myths ROGER BECK Toronto Dedicated to Reinhold Merkelbach, whose explorations of ancient narra- tive and the mystery cults have always seemed to me profoundly well oriented, even when I would not follow the same path in detail. This article is neither about a particular ancient novel nor about the genre of the ancient novel in general. But it is about story-telling in the ancient world, and about the metamorphosis which stories undergo when they pass through the crucible of religious invention. Its subject, then, is narrative fiction — narrative fiction as the construction of sacred myth and of myth’s dramatic counterpart, ritual performance. The fictions I shall explore are the myths and rituals of the Mithras cult. Some of these fictions, I shall argue, are elaborations of events and fantasies of the Neronian age: on the one hand, events in both Italy and the orient cen- tred on the visit of Tiridates of Armenia to Rome in 66; on the other hand, the heliomania of the times, a solar enthusiasm focused on, and in some measure orchestrated by, the emperor himself. What I am not offering is an explanation of Mithraism and its origins. In the first place, our subject is story and the metamorphosis of story, not relig- ion. In the second place, I would not presume to ‘explain’ Mithraism, or any other religion for that matter, by Euhemeristic reduction to a set of historical or pseudo-historical antecedents. In speaking of the ‘invention’ of Mithraism and of its ‘fictions’, moreover, I intend no disrespect. -

How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?

II. Old Norse Myth and Society HOW UNIFORM WAS THE OLD NORSE RELIGION? Stefan Brink ne often gets the impression from handbooks on Old Norse culture and religion that the pagan religion that was supposed to have been in Oexistence all over pre-Christian Scandinavia and Iceland was rather homogeneous. Due to the lack of written sources, it becomes difficult to say whether the ‘religion’ — or rather mythology, eschatology, and cult practice, which medieval sources refer to as forn siðr (‘ancient custom’) — changed over time. For obvious reasons, it is very difficult to identify a ‘pure’ Old Norse religion, uncorroded by Christianity since Scandinavia did not exist in a cultural vacuum.1 What we read in the handbooks is based almost entirely on Snorri Sturluson’s representation and interpretation in his Edda of the pre-Christian religion of Iceland, together with the ambiguous mythical and eschatological world we find represented in the Poetic Edda and in the filtered form Saxo Grammaticus presents in his Gesta Danorum. This stance is more or less presented without reflection in early scholarship, but the bias of the foundation is more readily acknowledged in more recent works.2 In the textual sources we find a considerable pantheon of gods and goddesses — Þórr, Óðinn, Freyr, Baldr, Loki, Njo3rðr, Týr, Heimdallr, Ullr, Bragi, Freyja, Frigg, Gefjon, Iðunn, et cetera — and euhemerized stories of how the gods acted and were characterized as individuals and as a collective. Since the sources are Old Icelandic (Saxo’s work appears to have been built on the same sources) one might assume that this religious world was purely Old 1 See the discussion in Gro Steinsland, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005). -

Examining the Transference Between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J

\ The Sword and the Cross: Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J. Decker III Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Manwell Ph. D .. Kalamazoo College Co-Chair of Classics Department I - A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degr~e of Bachelor of ~rts at - - Kalamazoo College. 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................... ~ .... : ......................................................ii I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs ............................... .1-21 II. Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity ............... ~ .. 23-38 III. Appendix .......................· ............................................................. 39 Bibliography .................... ·................................................................. 40-44 / 11 Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to my loving parents who made it possible to attend Kalamazoo College and allow me to further my studies in Classics. Without their financial and emotional support I would not have been able to complete this Senior Independent Project (SIP). Love you Mom and Dad! I am also deepl_y thankful to the Todd family and their generous grant, the Todd Memorial Classics Study Abroad Grant, which allowed me to travel to Italy and gain the inspiration for the topic of my SIP. I would like to express aspecial thanks to my SIP advisor Prof. Manwell, for putting up with all my procrastination and my challenging writing. I hope you didn't spend to many nights up late editing my drafts. Without all of you none of this would have been possible. Thank you very much. 1 I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs In the spring of 2011 an American atheist group put up a billboard in downtown New York City which read: "Born of a virgin on December 25th, known to his 12 disciples as "the Son of God, and resurrected three days after his death, we wish a Happy Birthday to Mithras, the mythical Persian god imagined over 600 years before that other guy .. -

In Words and Images

IN WORDS AND IMAGES 2017 Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 The Academy Is the Academy 50 Estonia as a Source of Inspiration Is the Academy... 5 Its Ponderous Birth 52 Other Bits About Us 6 Its Framework 7 Two Pictures from the Past 52 Top of the World 55 Member Ene Ergma Received a Lifetime Achievement Award for Science 12 About the fragility of truth Communication in the dialogue of science 56 Academy Member Maarja Kruusmaa, Friend and society of Science Journalists and Owl Prize Winner 57 Friend of the Press Award 57 Six small steps 14 The Routine 15 The Annual General Assembly of 19 April 2017 60 Odds and Ends 15 The Academy’s Image is Changing 60 Science Mornings and Afternoons 17 Cornelius Hasselblatt: Kalevipoja sõnum 61 Academy Members at the Postimees Meet-up 20 General Assembly Meeting, 6 December 2017 and at the Nature Cafe 20 Fresh Blood at the Academy 61 Academic Columns at Postimees 21 A Year of Accomplishments 62 New Associated Societies 22 National Research Awards 62 Stately Paintings for the Academy Halls 25 An Inseparable Part of the National Day 63 Varia 27 International Relations 64 Navigating the Minefield of Advising the 29 Researcher Exchange and Science Diplomacy State 30 The Journey to the Lindau Nobel Laureate 65 Europe “Mining” Advice from Academies Meetings of Science 31 Across the Globe 66 Big Initiatives Can Be Controversial 33 Ethics and Good Practices 34 Research Professorship 37 Estonian Academy of Sciences Foundation 38 New Beginnings 38 Endel Lippmaa Memorial Lecture and Memorial Medal 40 Estonian Young Academy of Sciences 44 Three-minute Science 46 For Women in Science 46 Appreciation of Student Research Efforts 48 Student Research Papers’ π-prizes Introduction ife in the Academy has many faces. -

Lääne-Saare Valla Ühisveevärgi Ja –Kanalisatsiooni Arendamise Kava Aastateks 2015—2026

LÄÄNE-SAARE VALLA ÜHISVEEVÄRGI JA –KANALISATSIOONI ARENDAMISE KAVA AASTATEKS 2015—2026 Lääne-Saare valla ühisveevärgi ja –kanalisatsiooni arendamise kava aastateks 2015—2026 SISUKORD 1 SISSEJUHATUS .................................................................................................................. 5 2 OLUKORRA KIRJELDUS ................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Arendamise kava koostamiseks vajalikud lähteandmed .......................................... 6 2.1.1 Veemajanduskava ............................................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Omavalitsuse arengukava ................................................................................ 8 2.1.3 Planeeringud .................................................................................................... 9 2.1.4 Vee erikasutusload ..........................................................................................10 2.1.5 Ühisveevärgi ja kanalisatsiooni arendamise kava ............................................13 2.1.6 Reovee kogumisalad .......................................................................................18 2.2 Keskkonna ülevaade ..............................................................................................20 2.2.1 Üldandmed ......................................................................................................20 2.2.2 Pinnakate ja selle ehitus ..................................................................................23 -

Ja Juhtimiskorralduse Mudelid Kohaliku Omavalitsuse Üksustes

Ekspertarvamus Detsentraliseeritud valitsemis- ja juhtimiskorralduse mudelid kohaliku omavalitsuse üksustes II Autor Mikk Lõhmus PhD +372 5119343 [email protected] 2021 1 SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Territoriaalsete valitsemis- ja juhtimiskorralduse mudelite aluspõhimõtetest .................................. 4 Osavallakogud ja teised kogukonna konsultatiivsed esinduskogud .................................................... 5 Teeninduskeskused ................................................................................................................................ 8 OLULISEMAD JÄRELDUSED .................................................................................................................... 9 SOOVITUSED ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Lisa 1 Osavallakogud 01.01.2021 .......................................................................................................... 12 Lisa 2: Kogukonnakogud 01.01.2021 .................................................................................................... 18 Lisa 3: Teeninduskeskused ja ametnike regionaalne paiknemine ....................................................... 23 Lisa 4 KOKS-i 8. peatüki muudatusettepanek ....................................................................................... 40 Sissejuhatus -

Igal Kandil Oma Lugu

Igal kandil oma lugu Valimik Võrumaa rahvajutte Võru, 2011 Väljaandja: Võrumaa Keskraamatukogu MTÜ Järjehoidja Projektijuht: Inga Kuljus Koostaja: Ere Raag Keeletoimetajad: Luule Lairand, Signe Pärnaste Esikaane pilt: Viive Kuks „Tamme-Lauri tamm“ Kujundus ja küljendus: Priit Pajusalu, Seri Disain OÜ Trükk: Trükikoda Ecoprint ISBN 978-9949-21-904-9 Täname raamatu väljaandmist toetanud Kohaliku Omaalgatuse Programmi, lugude jutustajaid ja kodukoha pärimuse üles kirjutajaid ning kogumiku valmimisele kaasaaitajaid! 3 Head lugejad! „Nagu tamm kasvamiseks oma jõu ammutab teda kandvast ja toitvast mullapinnast, samuti pead sina oma minevikust enesele elujõu ammutama, ega tohi sellest kunagi lahti lasta, et mitte kaduda või hävida.“ (Peeter Lindsaar, 1973) Võrumaa rahvaraamatukogude töötajad tegelevad järjepidevalt kodulootööga ja raamatukogude ajaloo uurimisega 1980. aastast alates. Arhiividesse on saadetud päringud raamatukogude asutamise ja tegevuse kohta, on tutvutud arhivaalidega, küsitletud endisi raamatukogutöötajaid ja kohaliku kultuurielu edendajaid. Saadud materjalide põhjal on koostatud kartoteegid ja raamatukogude ajalugu on talletatud kroonikaraamatutesse. Vabariiklikul rahva- raamatukogude kroonikate ülevaatusel 1983. aastal saavutati esikoht. Aastatel 2003–2006 kogutud materjalide põhjal koostati 2007. aastal s k Võrumaa rahvaraamatukogude ajalugu kajastav kogumik e s „Raamatukogud Võrumaal“ . Võrumaa Keskraamatukogu sajandi- u t pikkune tegevus koondati 2009. aastal sõnas ja pildis juubeliteosesse a h „Võrumaa Keskraamatukogu -

“Eesti Põlevloodusvarad Ja -Jäätmed” 2005.A

ISSN 1736-0315 Estonian Combustible Natural Resources and Wastes 2005 Eesti Põlevloodusvarad keemia chemistry vääristamine upgrading energeetika energetics ja -jäätmed keskkonnakaitse environmental protection Estanc AS, Silikaltsiidi 5c, 11216 Tallinn, Eesti, tel: 6 814 200, faks: 6 814 201, e-post: [email protected] nasõbralike kütuste tootmist, kasuta- The main fields of activity of the EBA mist, valdkonna teadus- ja arenduste- are: promotion of R & D on biomass gevust ning energiasäästu nii riigi applications; promotion of environmen- tasandil kui ka elanikkonna seas. tally friendly technologies and energy Põhjalikumalt on EBÜ tegevusest conservation; promotion of co-opera- kirjutatud ajakirjas Eesti Turvas alates tion with other interested partners at ühingu loomisaastast ja Eesti Põlevloo- home and abroad; dissemination of dusvarad ja -jäätmed (selles numbris information on and extension of EESTI BIOKÜTUSTE ÜHING veel lk 21). Alates käesolevast ajakirja knowledge about biomass via local/ numbrist on EBÜ selle vastutav välja- regional/international seminars and andja, kusjuures üks juhatuse liige information days and in various Eesti Biokütuste Ühing (EBÜ) loodi 21 osaleb ka toimetuskolleegiumi töös. publications, preparation of relevant asutajaliikme poolt Tallinnas 1998. Paljuski on EBÜ taastuvkütustealane training material; submission of aasta maikuus. Alates 1999. aasta tegevus suunatud tulevikku, sest proposals from grass root to national septembrist on EBÜ Euroopa Biomassi vastavalt Euroopa Liidu regulatsiooni- level for revision, and improvement of Assotsiatsiooni (AEBIOM) täievoliline dele peab liikmesmaades taastuva energy-related legislation in Estonia. liige. Praegu kuuluvad ühingusse kütuse ja energia osakaal riigis toode- The EBA has participated in and metsahoolduse, saematerjali tootmise tava kütuse ja energia hulgas lähiaas- contributed directly to various domestic ja töötlemise, jäätmete vääristamise, tatel märgatavalt suurenema. -

On Estonian Folk Culture: Pro Et Contra

doi:10.7592/FEJF2014.58.ounapuu ON ESTONIAN FOLK CULTURE: PRO ET CONTRA Piret Õunapuu Abstract: The year 2013 was designated the year of heritage in Estonia, with any kind of intangible and tangible heritage enjoying pride of place. Heritage was written and spoken about and revived in all kinds of ways and manners. The motto of the year was: There is no heritage without heir. Cultural heritage is a comprehensive concept. This article focuses, above all, on indigenous cultural heritage and, more precisely, its tangible (so-called object) part. Was the Estonian peasant, 120 years back, with his gradually increasing self-confidence, proud or ashamed of his archaic household items? Rustic folk culture was highly viable at that time. In many places people still wore folk costumes – if not daily, then at least the older generation used to wear them to church. A great part of Estonians still lived as if in a museum. Actually, this reminded of the old times that people tried to put behind them, and sons were sent to school in town for a better and more civilised future. In the context of this article, the most important agency is peasants’ attitude towards tangible heritage – folk culture in the widest sense of the word. The appendix, Pro et contra, at the end of the article exemplifies this on the basis of different sources. Keywords: creation of national identity, cultural heritage, Estonian National Museum, Estonian Students’ Society, folk costumes, folk culture, Learned Es- tonian Society, material heritage, modernisation, nationalism, social changes HISTORICAL BACKGROUND By the end of the 19th century, the Russification period, several cultural spaces had evolved in the Baltic countries: indigenous, German and Russian. -

Eesti Rahva Muuseumi Algaastate Suurkogumised 11

Eesti Rahva Muuseumi algaastate suurkogumised 11 EESTI RAHVA MUUSEUMI ALGAASTATE SUURKOGUMISED Piret Õunapuu Meie ei waiki, ei wäsi enne, kui iga lapsgi kü- las teab, mis Museum on, ja wiimne kui talu oma muistsused Museumile wälja on andnud. Kristjan Raud1 Sissejuhatus Eesti Rahva Muuseumi esemekogud on tänaseks päevaks kas- vanud umbes 133 000 esemeni2. Alus nendele kogudele pandi kohe pärast muuseumi asutamist, mil esimese kümne aastaga suudeti ko- guda ligi 20 000 eset, kusjuures nendest umbes kaks kolmandikku aastatel 1911–1913. Fenomen, et muuseum, kus tehti põhiliselt vaid ilma rahata tööd isamaa heaks, seadis endale eesmärgiks kogu Eesti- maa kihelkondade kaupa vanavarast tühjaks korjata ja suutis sellele tööle suunata kümneid ja kümneid inimesi, on kogu maailma aja- loos ilmselt ainulaadne. Tulemuseks on mitte ainult rohked, vaid ka väärtuslikud esemekogud, mis jõudsid muuseumisse enne laastavat Esimest maailmasõda. Käesolevas artiklis leiavad käsitlemist ainult esemelise vanavara korjamisega seotud kogumismatkad. Kõik teised muuseumi töösuu- nad nagu näiteks kihutuskõnede pidamine või väljanäituste korral- damine, mis samuti ühel või teisel moel on kogumistööga seotud, jäävad seekord tagaplaanile. Samuti jääb kõrvale „kohalike koguja- te” ja muuseumi usaldusmeeste töö. Seni on enim käsitletud Eesti Rahva Muuseumi varasemat ko- gumistööd eelkõige seoses Kristjan Raua isikuga. Kõige põhjaliku- ma ülevaate sellest annavad Hilja Silla artikkel „Kristjan Raud ja 1 Raud 1911a. 2 31.12.2006 seisuga oli Eesti Rahva Muuseumis esemekogus 132 880 ühikut. 12 Piret Õunapuu vanavara suurkogumine“ (1970) ning Rasmus Kangro-Pooli mono- graafi a Kristjan Raud (1961) peatükk „Kristjan Raud ja Eesti Rah- va Muuseum“. Lehti Viiroja oma raamatus Kristjan Rauast (1981) puudutab samuti ERMi vanavara kogumist seoses Kr. -

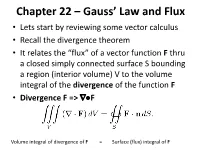

Chapter 22 – Gauss' Law and Flux

Chapter 22 – Gauss’ Law and Flux • Lets start by reviewing some vector calculus • Recall the divergence theorem • It relates the “flux” of a vector function F thru a closed simply connected surface S bounding a region (interior volume) V to the volume integral of the divergence of the function F • Divergence F => F Volume integral of divergence of F = Surface (flux) integral of F Mathematics vs Physics • There is NO Physics in the previous “divergence theorem” known as Gauss’ Law • It is purely mathematical and applies to ANY well behaved vector field F(x,y,z) Some History – Important to know • First “discovered” by Joseph Louis Lagrange 1762 • Then independently by Carl Friedrich Gauss 1813 • Then by George Green 1825 • Then by Mikhail Vasilievich Ostrogradsky 1831 • It is known as Gauss’ Theorem, Green’s Theorem and Ostrogradsky’s Theorem • In Physics it is known as Gauss’ “Law” in Electrostatics and in Gravity (both are inverse square “laws”) • It is also related to conservation of mass flow in fluids, hydrodynamics and aerodynamics • Can be written in integral or differential forms Integral vs Differential Forms • Integral Form • Differential Form (we have to add some Physics) • Example - If we want mass to be conserved in fluid flow – ie mass is neither created nor destroyed but can be removed or added or compressed or decompressed then we get • Conservation Laws Continuity Equations – Conservation Laws Conservation of mass in compressible fluid flow = fluid density, u = velocity vector Conservation of an incompressible fluid =