A Look at Two Groundings of Naval Vessels Separated by Over Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:43:06AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 04:24:08PM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

“Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 05:14:25AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Wish You a Very Happy Christmas and a Prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary

The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Issue Number 12: November 2008 £2.00; free to members Christmas Number and Special issue to mark the 90th Anniversary of the World War One Armistice In memory of Frederick Charles Wellard, grandfather of the new FOMA Membership Secretary, Betty Cole. The wooden cross, pictured, is a rare image of how the war graves appeared before their replacement by the now familiar rows of white stone. Frederick was killed at Arras, France, in August 1917. The front line diary records, ‘16/8/17 Normal trench routine. Trenches deepened where necessary. Enemy active with pineapples. S. Major Wellard killed. C.Q.M.S. Blackstock wounded (afterwards died).’ Three days later the battalion was relieved. Fred left a widow and five young children, three of whom, including Betty’s mother, Ivy, were sent to orphanages. More of Frederick’s story can be read inside. The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre wish you a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary At the 2008 FOMA AGM, it was decided that members should take on all the clerical responsibilities of the organisation, especially as we are all over the age of consent (some more so than others). In a moment of mental aberration I agreed to take on the role of Secretary. Aeons ago I had been paid to be the secretary to the Overseas Sales Director of a multi-national company and had had recent voluntary secretarial experience with another Friends group which I helped found. -

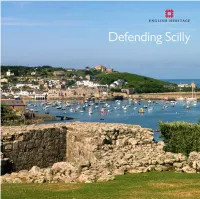

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England

The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England Celina Fox In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Royal Navy constituted by far the greatest enterprise in the country. Naval operations in and around the royal dockyards dwarfed civilian industries on account of the capital investment required, running costs incurred and logistical problems encountered. Like most state services, the Navy was not famed as a model of efficiency and innovation. Its day-to-day running was in the hands of the Navy Board, while a small Admiralty Board secretariat dealt with discipline and strategy. The Navy Board was responsible for the industrial organization of the Navy including the six royal dockyards; the design, construction and repair of ships; and the supply of naval stores. In practice its systems more or less worked, although they were heavily dependent on personal relationships and there were endless opportunities for confusion, delay and corruption. The Surveyor of the Navy, invariably a former shipwright and supposedly responsible for the construction and maintenance of all the ships and dockyards, should have acted as a coordinator but rarely did so. The labour force worked mainly on day rates and so had no incentive to be efficient, although a certain esprit de corps could be relied upon in emergencies.1 It was long assumed that an English shipwright of the period learnt his art of building and repairing ships primarily through practical training and experience gained on an apprenticeship, in contrast to French naval architects whose education was grounded on science, above all, mathematics. -

Frindsbury Cricketers Inside This Issue

The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Issue Number 11: August 2008 Frindsbury Cricketers This photograph from the collection of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre (FOMA) Chairman, Tessa Towner, will evoke memories of long hot (mythical) Kentish summers. Standing from left, John Walter (Tessa’s grandfather), 4th on left at back his brother Arthur (with peaked cap), known as Tom. Seated with cap, another brother, George Walter, landlord of the Royal Oak pub, Frindsbury. Also in the photo are probably several of the seven Skilton brothers, it was their father Joseph Skilton along with the Rev Jackson, vicar of Frindsbury, who started the Cricket Club in 1885. The date of the photograph has been narrowed down to about 1907 to 1909. Other possible names playing at this time were the Anderson brothers Colin and Donald (both killed in WWI), W.J.Coleman, A.Francis, H.Harpum, M.W.Lewry, A.Lines, A.E.Loach, N.McKechnie, D.Nye, and A.Ring. Inside this issue... We say goodbye to Stephen Dixon, Borough Archivist. After 18 years at the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre, Stephen left in June for a new post as Archive Service Manager at Essex Record Office, Chelmsford. One of Stephen’s farewell gifts was a framed photograph, taken by FOMA Chairman Tessa Towner, of him on his boat, taken from the Kingswear Castle during the trip on Saturday 31st May 2008 to follow the 100th Medway Barge Match. About The Clock Tower The Clock Tower is the quarterly journal produced and published by the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre (FOMA). -

The 1711 Expedition to Quebec: Politics and the Limitations

THE 1711 EXPEDITION TO QUEBEC: POLITICS AND THE LIMITATIONS OF GLOBAL STRATEGY IN THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE ADAM JAMES LYONS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT To mark the 300th anniversary of the event in question, this thesis analyses the first British attempt to conquer the French colonial city of Quebec. The expedition was a product of the turbulent political environment that was evident towards the end of the reign of Queen Anne. Its failure has consequently proven to be detrimental to the reputations of the expedition‘s commanders, in particular Rear-Admiral Sir Hovenden Walker who was actually a competent and effective naval officer. True blame should lie with his political master, Secretary of State Henry St John, who ensured the expedition‘s failure by maintaining absolute control over it because of his obsession with keeping its objective a secret. -

Save Our Ships! Navigation on the High Seas

Save Our Ships! Navigation on the High Seas Introduction Navigation is determining where you are and how to get where you're going. Navigation tools help you travel from one place to another efficiently and safely. Early sea navigation depended upon a mariner's ability to determine latitude by observing the height of the sun in daylight and the North Star and major constellations at night. Such observations were not exact and could be unreliable. Beginning in the 13th century, advancements in navigational tools and scientific methods made navigation more exact and travel by ship safer; however, by the early 18th century, ships still lost their way frequently, with sometimes disastrous results. In this problem- based lesson, students read about the Scilly disaster of 1707, determine its causes, and then choose and explain which navigational tools might have prevented the disaster. Objectives In this lesson, students: • identify the cause(s) of the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 • place the development of navigational tools in chronological order • problem-solve to figure out what navigational tools could have prevented the Scilly disaster • use their knowledge of navigational tools to answer the question “How did mariners use navigational tools to solve the challenges of early oceanic travel?” Materials • Navigational Tools Graphic Organizer • Scilly Naval Disaster of 1707 • Timeline of the Development of Navigational Tools • Navigational Tools Cards • scissors • tape © 2015 The Colonial  ƒoundation 1 Save Our Ships! Navigation on the High Seas Strategy 1. Ask students to think about the kinds of tools we have today to help us find our way when traveling. -

SHOVELL and the LONGITUDE How the Death of Crayford’S Famous Admiral Shaped the Modern World

SHOVELL AND THE LONGITUDE How the death of Crayford’s famous admiral shaped the modern world Written by Peter Daniel With Illustrations by Michael Foreman Contents 1 A Forgotten Hero 15 Ships Boy 21 South American Adventure 27 Midshipman Shovell 33 Fame at Tripoli 39 Captain 42 The Glorious Revolution 44 Gunnery on the Edgar 48 William of Orange and the Troubles of Northern Ireland 53 Cape Barfleur The Five Days Battle 19-23 May 1692 56 Shovell comes to Crayford 60 A Favourite of Queen Anne 65 Rear Admiral of England 67 The Wreck of the Association 74 Timeline: Sir Cloudsley Shovell 76 The Longitude Problem 78 The Lunar Distance Method 79 The Timekeeper Method 86 The Discovery of the Association Wreck 90 Education Activities 91 Writing a Newspaper Article 96 Design a Coat of Arms 99 Latitude & Longitude 102 Playwriting www.shovell1714.crayfordhistory.co.uk Introduction July 8th 2014 marks the tercentenary of the Longitude Act (1714) that established a prize for whoever could identify an accurate method for sailors to calculate their longitude. Crayford Town Archive thus have a wonderful opportunity to tell the story of Sir Cloudesley Shovell, Lord of the Manor of Crayford and Rear Admiral of England, whose death aboard his flagship Association in 1707 instigated this act. Shovell, of humble birth, entered the navy as a boy (1662) and came to national prominence in the wars against the Barbary pirates. Detested by Pepys, hated by James II, Shovell became the finest seaman of Queen Anne’s age. In 1695 he moved to Crayford after becoming the local M.P. -

The Westminster Model Navy: Defining the Royal Navy, 1660-1749

The Westminster Model Navy: Defining the Royal Navy, 1660-1749 Samuel A. McLean PhD Thesis, Department of War Studies May 4, 2017 ABSTRACT At the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, Charles II inherited the existing interregnum navy. This was a persistent, but loosely defined organization that included a professional community of officers, a large number of warships, and substantial debts. From the beginning Charles II used royal prerogative to define the Royal Navy. In 1661, Parliament created legislation that simultaneously defined the English state and the Royal Navy. These actions closely linked the Royal Navy’s development to that of the English state, and the use of both statutes and conventions to define the Navy provided the foundation for its development in the ‘Westminster Model’. This thesis considers the Royal Navy’s development from the Restoration to the replacement of the Articles of War in 1749 in five distinct periods. The analysis shows emphasizes both the consistency of process that resulted from the creation and adoption of definitions in 1660, as well as the substantial complexity and differences that resulted from very different institutional, political and geopolitical circumstances in each period. The Royal Navy’s development consisted of the ongoing integration of structural and professional definitions created both in response to crises and pressures, as well as deliberate efforts to improve the institution. The Royal Navy was integrated with the English state, and became an institution associated with specific maritime military expertise, and the foundations laid at the Restoration shaped how the Navy’s development reflected both English state development and professionalization.