Conreport-Of-The-Consult-87-Processsult-87-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Institutions

Ministry of Government Services Information Access & Privacy Directory of Institutions What is the Directory of Institutions? The Directory of Institutions lists and provides contact information for: • Ontario government ministries, agencies, community colleges and universities covered by FIPPA • Municipalities and other local public sector organizations such as school boards, library boards and police services covered by MFIPPA These organizations are all called "institutions" under the Acts. The address of the FIPPA or MFIPPA Coordinator for each institution is provided to assist you in directing requests for information to the correct place. FIPPA Coordinators • Provincial Ministries • Provincial Agencies, Boards and Commissions • Colleges and Universities • Hospitals MFIPPA Coordinators • Boards of Health • Community Development Corporations • Conservation Authorities • Entertainment Boards • District Social Services Administration Boards • Local Housing Corporations • Local Roads Boards • Local Services Boards • Municipal Corporations • Planning Boards • Police Service Boards • Public Library Boards • School Boards • Transit Commissions FIPPA Coordinators Provincial Ministries MINISTRY OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 160 Bloor Street East, 4th Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2E6 Phone: 416-326-4740 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 2nd Floor NW, 1 Stone Rd. W. Guelph, ON N1G 4Y2 Phone: 519-826-3100 ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 134 Ian Macdonald Blvd Toronto, ON M7A 2C5 Phone: 416-327-1563 MINISTRY OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator McMurty-Scott Building 5th Floor, 720 Bay St. Toronto, ON M5G 2K1 Phone: 416-326-4305 CABINET OFFICE Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator Whitney Block, Room 4500 99 Wellesley St. -

The Fiddlers of James Bay: Transatlantic Flows and Musical Indigenization Among the James Bay Cree

The Fiddlers of James Bay: Transatlantic Flows and Musical Indigenization among the James Bay Cree FRANCES WILKINS Abstract: Fiddle music and dancing have formed a major component of the social lives of the Algonquian 57-99. 40 (1): First Nations Cree population living in the James Bay region of Ontario and Québec since the instrument and its associated repertoire were introduced to the region by British (and most notably Scottish) employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company who travelled across the Atlantic on ships from the late 17th to the 20th MUSICultures century. Based on archival research and ongoing fieldwork in the region since 2011, this article aims to explore this transatlantic musical migration from the British Isles to James Bay and the reshaping of Scottish fiddle music and dance through indigenization and incorporation into the Cree cultural milieu. By examining this area of cultural flow, the article seeks to engage with current themes in ethnomusicology on the subject and add to the growing body of knowledge surrounding them. Résumé : La danse et le violon ont constitué une composante majeure de la vie sociale de la population algonquienne de la Première nation cri vivant dans la région de la baie James, en Ontario et au Québec, puisque cet instrument et le répertoire qui lui était associé furent introduits dans la région par les employés britanniques (et plus particulièrement écossais) de la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson, qui ont traversé l’Atlantique à partir de la fin du 17e siècle jusqu’au 20e siècle. Cet article, qui se fonde sur une recherche en archives et un travail de terrain continu dans la région depuis 2011, cherche à explorer cette migration musicale transatlantique depuis les îles britanniques jusqu’à la baie James, ainsi que le remodelage et la reconstitution de la musique au violon et de la danse écossaise par le biais de leur indigénisation dans le milieu culturel cri. -

Working As a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow

WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY HERE TO STAY, GONE TOMORROW: WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY By JENNIFER MARIE DAWSON, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial FulfIllment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Jennifer Marie Dawson, September 1995 MASTER OF ARTS (1995) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow: Working as a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory AUTHOR: Jennifer Marie Dawson, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Wayne Warry NUMBER OF PAGES: iv, 264 11 ABSTRACT The experience of a service provider living and working in Moosonee and Moose Factory is largely determined by whether the individual is Cree and from these communities, or is non-Native and from "the south". This study examines these experiences in terms of stress and coping, loosely adopting and occasionally critiquing Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) definitions of these concepts. The cultural and historical factors which influence stress and coping are emphasized without denying the importance of contemporary circumstances in these politically and socially turbulent communities. Non-Native or "southern" service providers are outsiders. They are kept at a distance both by their own interpretation of and reaction to "difference" and by others who are suspicious of their motivations and commitment. Some cope with their outsider status by reinforcing it; they withdraw from active personal and professional participation in community. But instead of refusing to change and clinging desperately to what is familiar, those southerners who have remained the longest in these northern locales are willing to acknowledge the relevance and rewards of different ways of living and working. -

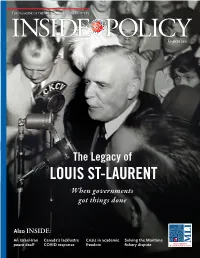

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D

ARCTIC VOL. 56, NO. 2 (JUNE 2003) P. 159–167 Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D. SHORTHOUSE,1 HENRI GOULET2 and DAVID P. SHORTHOUSE3 (Received 22 November 2001; accepted in revised form 19 August 2002) ABSTRACT. A brief collecting trip to Fort Severn, Ontario (55˚59' N, 87˚38' W), in May 2001 revealed galls of three species of cynipid wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) on the wild rose Rosa acicularis. Roses and cynipid galls occur along the banks of the Severn River above the tree line because of clay deposits, heat, and rafts of vegetation carried north by the river. Ground beetles and spiders were collected with pitfall traps. Our identification of 15 species of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae), two of them new records for Ontario, and 11 species of ground spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae), all new records for northwestern Ontario, indicates that the invertebrate fauna in the area has been poorly studied. Roads and trails away from Fort Severn, regularly scheduled airline service, and convenient accommodations make the area ideal for biological studies. Key words: cynipid galls, wild roses, ground beetles, ground-dwelling spiders, Fort Severn RÉSUMÉ. Une brève sortie de prélèvement à Fort Severn, en Ontario (55˚ 59' de lat. N., 87˚ 38' de long. O.), effectuée en mai 2001 a révélé l’existence de galles de trois espèces de cynips du rosier (hyménoptères: cynipidés) sur le rosier aciculaire Rosa acicularis. On trouve ce dernier et les galles du rosier le long des rives de la Severn au-dessus de la limite forestière en raison des dépôts d’argile, de la chaleur et de la végétation flottante que transporte la rivière en direction du Nord. -

“Moose Factory Is My Home”: Mocreebec's Struggle for Recognition and Self-Determination

“Moose Factory Is My Home”: MoCreebec’s Struggle for Recognition and Self-Determination A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of the Masters of Arts in Anthropology In the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology By Kota Kimura Copyright Kota Kimura, May 2016. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this the- sis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is under- stood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i Abstract This thesis, based on my ethnographic research in Moose Factory, Ontario documents the his- tory of MoCreebec people from the early Twentieth Century to the present. -

2018-09-20-Om-Moose-Factory-Fn

Climate Change Impacts on Water and Wastewater Infrastructure at Moose Factory Final Report July 24, 2018 Project No. 163401448 Prepared by: Developed in partnership with: Sign-off Sheet This document entitled Climate Change Impacts on Water and Wastewater Infrastructure at Moose Factory was prepared by Stantec Consulting Ltd. (“Stantec”) for the account of Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation (OFNTSC) (the “Client”). Any reliance on this document by any third party is strictly prohibited. The material in it reflects Stantec’s professional judgment in light of the scope, schedule and other limitations stated in the document and in the contract between Stantec and the Client. The opinions in the document are based on conditions and information existing at the time the document was published and do not take into account any subsequent changes. In preparing the document, Stantec did not verify information supplied to it by others. Any use which a third party makes of this document is the responsibility of such third party. Such third party agrees that Stantec shall not be responsible for costs or damages of any kind, if any, suffered by it or any other third party as a result of decisions made or actions taken based on this document. Prepared by (signature) Guy Félio, Ph.D., P.Eng. Prepared by (signature) Wayne L.E. Penno, MBA, P.Eng. Reviewed by (signature) Jordan Stewart, P.Eng. Approved by (signature) Adrien Comeau, M.Eng, P.Eng CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON WATER AND WASTEWATER INFRASTRUCTURE AT MOOSE FACTORY Table of Contents -

MOOSE CREE FIRST NATION's SPEAKING NOTES ON

MOOSE CREE FIRST NATION’s SPEAKING NOTES ON PROTECTED AREAS TO THE FEDERAL STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT For presentation on October 18, 2016 Chief Patricia Faries Jack Rickard, Director of Lands and Resources ([email protected]) Introduction: Good afternoon, Thank you for this opportunity to share with the Committee our perspective on protected areas and conservation objectives. Also, I would like to acknowledge the traditional territory of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan. It is an honour to come before you and share our thoughts as Indigenous People. My name is Patricia Faries and I am joined by our Director of Lands and Resources Jack Rickard. We are from the Moose Cree First Nation and we have recently made our reaffirmation of our Homelands Declaration on September 27, 2016. Our home community is located on Moose Factory Island within the Moose River Delta. Our Moose Cree Homelands extend from Hearst, Ontario in the west just beyond the Quebec border in the east, and from south of Highway 11 to points north toward the Albany River. “Homelands” are the areas that are determined by the MCFN citizens (Eh- lilu-wuk) which is inclusive generally of the historical occupancy and use of lands and watersheds in the Northeastern Ontario. The Moose Cree Homelands is comprised of static boundaries and covers approximately 60,000 sq. km. As the Moose Cree have determined, Homelands include surface and subsurface lands, water and air. The Homeland areas have been derived using Moose Cree Knowledge from our Elders and are based on continued presence of hunting, trapping and harvest grounds prior to the Ontario government trapline system existed. -

Myontario a Vision Over Time

Heritage Matters A publication of the Ontario Heritage Trust February 2017 MyOntario A vision over time OntarioHeritageTrust heritagetrust.on.ca @ONheritage ElginWinterGardenTheatres TODDS SUBMISSION Our cover: Highway 11, near Hearst By Todd Stewart – artist and former Doris McCarthy Artist-in-Residence program resident I feel the deepest connection with a place when I’m alone in it, surrounded by silence, the rest of the world far away. The stillness stops time and clears my mind. For me, a certain place stands out among many – Highway 11, the northern route across Ontario. I’ve driven along this road several times, not enough for it to become routine but enough for it to have a lasting memory. I find the long unbroken stretch of spruce and pine, bisected by the simple two-lane highway, to be far from boring – a contemplative and reassuring space, particularly at that moment right after sundown before darkness takes over. Stepping out of the car and turning off the engine, I sit alone in complete quiet; no vehicles pass by, the air is completely still. It seems strange for a highway to be a place that allows an experience such as this, but for a fleeting moment I allow myself to believe that I’m really in the middle of nowhere, away from time. Todd Stewart at Fool’s Paradise with his silkscreen “Untitled (Lake Ontario),” completed during his DMAiR residency. This issue of Heritage Matters, published in English and French, has a combined This publication is printed on recycled paper using vegetable circulation of 28,000. -

Community Profiles – James and Hudson Bay Region

WEENEEBAYKO AREA HEALTH AUTHORITY Providing primary care medical and nursing services; pre-hospital care; mental health and traditional healing services; dental health services; rehabilitation services; diagnostic imagining; diabetes education and support services and home and community care support; the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA) is a unified, integrated First Nation Regional Health Authority located on the west coast of James Bay in Northern Ontario. We provide health care to the following six communities in the Mushkegowuk Territory: MOOSE FACTORY, Ontario Moose Factory is home to the Moose Cree First Nation and is a community located on Moose Factory Island at the southern tip of James Bay. Founded in 1673 by the Hudson’s Bay Company as a fur trading post, Moose Factory is one of the oldest English-speaking settlements in Ontario and is home to approximately 2,700 residents, most of whom are Moose Cree First Nation members. Moose Factory is only accessible by water in the spring, summer and fall seasons; ice road in the winter months and helicopter in between. Air Ambulance services are required to medevac patients to this regional facility from the catchment area. The Weeneebayko General Hospital provides regional health care services and is located in Moose Factory. It is a 37 bed facility with a staff of 12 full time physicians, who also provide medical services to each of the remaining five communities on a rotational basis. A full OR suite; emergency services; obstetrical services; general medical-surgical; pediatrics; alternative level of care and palliative care services are located in this facility; along with a wide range of outpatient and regional community based services, including diagnostic imaging; rehabilitation; laboratory, dental and audiology services; primary care outpatient clinics; diabetes programs; dental program and the traditional healing program. -

OFO Bird Finding Guide #6

32 OFO Bird Finding Guide #6 A Birder's Guide to Southern James Bay, Including Moosonee and Moose Factory Stephen 1. Scholten Introduction in the region. This guide is intended to introduce Birding this area most effec experienced birders and naturalists, tively requires coverage of the as well as casual visitors, to the bird range of habitats found near the vil ing opportunities available in the lages, as well as on the coast. southern James Bay area. It pro Walking the townsites of Moosonee vides directions to, and descriptions and Moose Factory will yield birds of, different locations and habitats of disturbed habitats, willow thick that may be of interest to birders ets' shorelines, upland spruce and and naturalists. It also describes poplar woods, and freshwater some of the trail systems which, marshes. A trip to the coast, either though not intended for birding, for a day to Shipsands Island or offer easily accessible walks White Top, or for several days of through a variety of habitats in the camping at a more distant site, will area. The main attractions of the offer more extensive freshwater Moosonee area to birders are the marshes, as well as brackish and salt wide diversity of habitats, many of marshes, the open waters and van which are uncommon or non-exis tage points of James Bay, and tent in other parts of the province, potentially large numbers of and the relatively easy access con migrants associated with these sidering the northern location. habitats. If your visit coincides with Habitat types include boreal forest spring or fall migration, you can on coastal beach ridges and well expect large numbers of sparrows, drained river banks, bogs and fens warblers and finches in the dis in the lowland interior, coastal habi turbed habitats, thickets and wood tats such as freshwater and salt lands, and large numbers of shore marsh, mud flats, and ponds. -

Directory of Institutions

Ministry of Government Services Information Access & Privacy Directory of Institutions What is the Directory of Institutions? The Directory of Institutions lists and provides contact information for: • Ontario government ministries, agencies, community colleges and universities covered by FIPPA • Municipalities and other local public sector organizations such as school boards, library boards and police services covered by MFIPPA These organizations are all called "institutions" under the Acts. The address of the FIPPA or MFIPPA Coordinator for each institution is provided to assist you in directing requests for information to the correct place. FIPPA Coordinators • Provincial Ministries • Provincial Agencies, Boards and Commissions • Colleges and Universities • Hospitals MFIPPA Coordinators • Boards of Health • Community Development Corporations • Conservation Authorities • Entertainment Boards • District Social Services Administration Boards • Local Housing Corporations • Local Roads Boards • Local Services Boards • Municipal Corporations • Planning Boards • Police Service Boards • Public Library Boards • School Boards • Transit Commissions FIPPA Coordinators Provincial Ministries MINISTRY OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 160 Bloor Street East, 4th Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2E6 Phone: 416-326-4740 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 2nd Floor NW, 1 Stone Rd. W. Guelph, ON N1G 4Y2 Phone: 519-826-3100 ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 134 Ian Macdonald Blvd Toronto, ON M7A 2C5 Phone: 416-327-1563 MINISTRY OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator McMurty-Scott Building 5th Floor, 720 Bay St. Toronto, ON M5G 2K1 Phone: 416-326-4305 CABINET OFFICE Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator Whitney Block, Room 4500 99 Wellesley St.