Six Moose Factory Cree Life Histories Six Moose Factory Cree Life Histories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit Kapuskasing Iroquois Falls Hearst Timmins Porcupine Cochrane Moosonee Hornepayne Matheson Smooth Rock Falls Population Profile Foyez Haque, MBBS, MHSc Public Health Epidemiologist published by: Th e Porcupine Health Unit Timmins, Ontario October 2009 ©2009 Population Profile - 2006 Census Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to those without whose support this Population Profile would not be published. First of all, I would like to thank the management committee of the Porcupine Health Unit for their continuous support of and enthusiasm for this publication. Dr. Dennis Hong deserves a special thank you for his thorough revision. Thanks go to Amanda Belisle for her support with editing, creating such a wonderful cover page, layout and promotion of the findings of this publication. I acknowledge the support of the Statistics Canada for history and description of the 2006 Census and also the definitions of the variables. Porcupine Health Unit – 1 Population Profile - 2006 Census 2 – Porcupine Health Unit Population Profile - 2006 Census Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 1 Preface . 5 Executive Summary . 7 A Brief History of the Census in Canada . 9 A Brief Description of the 2006 Census . 11 Population Pyramid. 15 Appendix . 31 Definitions . 35 Table of Charts Table 1: Population distribution . 12 Table 2: Age and gender characteristics. 14 Figure 3: Aboriginal status population . 16 Figure 4: Visible minority . 17 Figure 5: Legal married status. 18 Figure 6: Family characteristics in Ontario . 19 Figure 7: Family characteristics in Porcupine Health Unit area . 19 Figure 8: Low income cut-offs . 20 Figure 11: Mother tongue . -

(De Beers, Or the Proponent) Has Identified a Diamond

VICTOR DIAMOND PROJECT Comprehensive Study Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Overview and Background De Beers Canada Inc. (De Beers, or the Proponent) has identified a diamond resource, approximately 90 km west of the First Nation community of Attawapiskat, within the James Bay Lowlands of Ontario, (Figure 1-1). The resource consists of two kimberlite (diamond bearing ore) pipes, referred to as Victor Main and Victor Southwest. The proposed development is called the Victor Diamond Project. Appendix A is a corporate profile of De Beers, provided by the Proponent. Advanced exploration activities were carried out at the Victor site during 2000 and 2001, during which time approximately 10,000 tonnes of kimberlite were recovered from surface trenching and large diameter drilling, for on-site testing. An 80-person camp was established, along with a sample processing plant, and a winter airstrip to support the program. Desktop (2001), Prefeasibility (2002) and Feasibility (2003) engineering studies have been carried out, indicating to De Beers that the Victor Diamond Project (VDP) is technically feasible and economically viable. The resource is valued at 28.5 Mt, containing an estimated 6.5 million carats of diamonds. De Beers’ current mineral claims in the vicinity of the Victor site are shown on Figure 1-2. The Proponent’s project plan provides for the development of an open pit mine with on-site ore processing. Mining and processing will be carried out at an approximate ore throughput of 2.5 million tonnes/year (2.5 Mt/a), or about 7,000 tonnes/day. Associated project infrastructure linking the Victor site to Attawapiskat include the existing south winter road and a proposed 115 kV transmission line, and possibly a small barge landing area to be constructed in Attawapiskat for use during the project construction phase. -

Final Report on Facilitated Community Sessions March 2020

FINAL REPORT ON FACILITATED COMMUNITY SESSIONS MARCH 2020 MCLEOD WOOD ASSOCIATES INC. #201-160 St David St. S., Fergus, ON N1M 2L3 phone: 519 787 5119 Selection of a Preferred Location for the New Community Table Summarizing Comments from Focus Groups Contents The New Community – a Five Step Process .................................................................................... 2 Background: ................................................................................................................................ 2 Steps Leading to Relocation: ................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Steps Two and Three .......................................................................................... 4 Summary of the Focus Group Discussions: ............................................................................. 5 Appendix One: Notes from Moose Factory Meeting held November 26 2019…………………………17 Appendix Two: Notes from Moosonee Meeting held November 28 2019………………………………23 1 Selection of a Preferred Location for the New Community Table Summarizing Comments from Focus Groups The New Community – a Five Step Process Background: The MoCreebec Council of the Cree Nation was formed on February 6, 1980 to contend with economic and health concerns and the social housing conditions facing the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) beneficiaries that lived in Moose Factory and Moosonee. The JBNQA beneficiaries were mainly registered with three principal bands -

Five Nations Energy Inc

Five Nations Energy Inc. Presented by: Edward Chilton Secretary/Treasurer And Lucie Edwards Chief Executive Officer Where we are James Bay area of Ontario Some History • Treaty 9 signed in 1905 • Treaty Organization Nishnawbe Aski Nation formed early 1970’s • Mushkegowuk (Tribal) Council formed late 1980’s • 7 First Nations including Attawapiskat, Kashechewan, Fort Albany • Fort Albany very early trading post early 1800’s-Hudson Bay Co. • Attawapiskat historical summer gathering place-permanent community late 1950’s • Kashechewan-some Albany families moved late 1950’s History of Electricity Supply • First energization occurred in Fort Albany- late 1950’s Department of Defense Mid- Canada radar base as part of the Distant Early Warning system installed diesel generators. • Transferred to Catholic Mission mid 1960’s • Distribution system extended to community residents early 1970’s and operated by Ontario Hydro • Low Voltage (8132volts) line built to Kashechewan mid 1970’s, distribution system built and operated by Ontario Hydro • Early 1970’s diesel generation and distribution system built and operated by Ontario Hydro • All based on Electrification agreement between Federal Government and Ontario Provincial Crown Corporation Ontario Hydro Issues with Diesel-Fort Albany Issues with Diesel-Attawapiskat • Fuel Spill on River From Diesel To Grid Based Supply • Early 1970’s - Ontario Hydro Remote Community Systems operated diesel generators in the communities • Federal Government (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada-INAC) covered the cost for -

FINAL 2009 Annual Report

NEOnet 2009 Annual Report Infrastructure Enhancement Application Education and Awareness 2009 Annual Report Table of Contents Message from the Chair ..............................................................................................2 Corporate Profile........................................................................................................3 Mandate ....................................................................................................................3 Regional Profile ..........................................................................................................4 Catchment Area.......................................................................................................................................................5 NEOnet Team .............................................................................................................6 Organizational Chart..............................................................................................................................................6 Core Staff Members...............................................................................................................................................7 Leaving staff members..........................................................................................................................................8 Board of Directors ..................................................................................................................................................9 -

Directory of Institutions

Ministry of Government Services Information Access & Privacy Directory of Institutions What is the Directory of Institutions? The Directory of Institutions lists and provides contact information for: • Ontario government ministries, agencies, community colleges and universities covered by FIPPA • Municipalities and other local public sector organizations such as school boards, library boards and police services covered by MFIPPA These organizations are all called "institutions" under the Acts. The address of the FIPPA or MFIPPA Coordinator for each institution is provided to assist you in directing requests for information to the correct place. FIPPA Coordinators • Provincial Ministries • Provincial Agencies, Boards and Commissions • Colleges and Universities • Hospitals MFIPPA Coordinators • Boards of Health • Community Development Corporations • Conservation Authorities • Entertainment Boards • District Social Services Administration Boards • Local Housing Corporations • Local Roads Boards • Local Services Boards • Municipal Corporations • Planning Boards • Police Service Boards • Public Library Boards • School Boards • Transit Commissions FIPPA Coordinators Provincial Ministries MINISTRY OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 160 Bloor Street East, 4th Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2E6 Phone: 416-326-4740 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 2nd Floor NW, 1 Stone Rd. W. Guelph, ON N1G 4Y2 Phone: 519-826-3100 ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 134 Ian Macdonald Blvd Toronto, ON M7A 2C5 Phone: 416-327-1563 MINISTRY OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator McMurty-Scott Building 5th Floor, 720 Bay St. Toronto, ON M5G 2K1 Phone: 416-326-4305 CABINET OFFICE Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator Whitney Block, Room 4500 99 Wellesley St. -

New Post Creek Project News

New Post Creek Project News Newsletter #8 April 2012 President’s Message It has been approximately 10 months since I came on board as President of Coral Rapids Power and a lot has happened since then. This position has given me the opportunity to learn from experienced team members and build my skills. The sup- port and encouragement from the New Post Creek project team makes this part of the job enjoyable. The New Post Creek project entered into the Definition Phase in May 2011, and a year later we have completed a lot of work, but there is a lot left to do before we can start con- struction. We are mostly working on the engineering and the Environmental Assessment at this time. The Environmental Assessment commenced in Novem- ber 2011 and included the Aboriginal and Public Consulta- tion Open Houses that were held in late November. We visited Moose Cree First Nation in Moose Factory on the 28th and gave an introduction of the project. The participants at this meeting were quite positive about the project and the informa- tion was well received. There was a genuine interest in the im- pacts on fish habitat and on the Moose Cree member’s trapline that is near the proposed transmission line route. TTN mem- bers in Moosonee attended a community meeting that evening at the curling club in Moosonee. On Nov 29th a community meeting was held for TTN members at the reserve. This was a great chance to talk about the project with other community members and hear their thoughts on everything. -

The Fiddlers of James Bay: Transatlantic Flows and Musical Indigenization Among the James Bay Cree

The Fiddlers of James Bay: Transatlantic Flows and Musical Indigenization among the James Bay Cree FRANCES WILKINS Abstract: Fiddle music and dancing have formed a major component of the social lives of the Algonquian 57-99. 40 (1): First Nations Cree population living in the James Bay region of Ontario and Québec since the instrument and its associated repertoire were introduced to the region by British (and most notably Scottish) employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company who travelled across the Atlantic on ships from the late 17th to the 20th MUSICultures century. Based on archival research and ongoing fieldwork in the region since 2011, this article aims to explore this transatlantic musical migration from the British Isles to James Bay and the reshaping of Scottish fiddle music and dance through indigenization and incorporation into the Cree cultural milieu. By examining this area of cultural flow, the article seeks to engage with current themes in ethnomusicology on the subject and add to the growing body of knowledge surrounding them. Résumé : La danse et le violon ont constitué une composante majeure de la vie sociale de la population algonquienne de la Première nation cri vivant dans la région de la baie James, en Ontario et au Québec, puisque cet instrument et le répertoire qui lui était associé furent introduits dans la région par les employés britanniques (et plus particulièrement écossais) de la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson, qui ont traversé l’Atlantique à partir de la fin du 17e siècle jusqu’au 20e siècle. Cet article, qui se fonde sur une recherche en archives et un travail de terrain continu dans la région depuis 2011, cherche à explorer cette migration musicale transatlantique depuis les îles britanniques jusqu’à la baie James, ainsi que le remodelage et la reconstitution de la musique au violon et de la danse écossaise par le biais de leur indigénisation dans le milieu culturel cri. -

North Lake Superior Métis

The Historical Roots of Métis Communities North of Lake Superior Gwynneth C. D. Jones Vancouver, B. C. 31 March 2015. Prepared for the Métis Nation of Ontario Table of Contents Introduction 3 Section I: The Early Fur Trade and Populations to 1821 The Fur Trade on Lakes Superior and Nipigon, 1600 – 1763 8 Post-Conquest Organization of the Fur Trade, 1761 – 1784 14 Nipigon, Michipicoten, Grand Portage, and Mixed-Ancestry Fur Trade Employees, 1789 - 1804 21 Grand Portage, Kaministiquia, and North West Company families, 1799 – 1805 29 Posts and Settlements, 1807 – 1817 33 Long Lake, 1815 – 1818 40 Michipicoten, 1817 – 1821 44 Fort William/Point Meuron, 1817 – 1821 49 The HBC, NWC and Mixed-Ancestry Populations to 1821 57 Fur Trade Culture to 1821 60 Section II: From the Merger to the Treaty: 1821 - 1850 After the Merger: Restructuring the Fur Trade and Associated Populations, 1821 - 1826 67 Fort William, 1823 - 1836 73 Nipigon, Pic, Long Lake and Michipicoten, 1823 - 1836 79 Families in the Lake Superior District, 1825 - 1835 81 Fur Trade People and Work, 1825 - 1841 85 "Half-breed Indians", 1823 - 1849 92 Fur Trade Culture, 1821 - 1850 95 Section III: The Robinson Treaties, 1850 Preparations for Treaty, 1845 - 1850 111 The Robinson Treaty and the Métis, 1850 - 1856 117 Fur Trade Culture on Lake Superior in the 1850s 128 After the Treaty, 1856 - 1859 138 2 Section IV: Persistence of Fur Trade Families on Lakes Superior and Nipigon, 1855 - 1901 Infrastructure Changes in the Lake Superior District, 1863 - 1921 158 Investigations into Robinson-Superior Treaty paylists, 1879 - 1899 160 The Dominion Census of 1901 169 Section V: The Twentieth Century Lake Nipigon Fisheries, 1884 - 1973 172 Métis Organizations in Lake Nipigon and Lake Superior, 1971 - 1973 180 Appendix: Maps and Illustrations Watercolour, “Miss Le Ronde, Hudson Bay Post, Lake Nipigon”, 1867?/1901 Map of Lake Nipigon in T. -

Working As a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow

WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY HERE TO STAY, GONE TOMORROW: WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY By JENNIFER MARIE DAWSON, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial FulfIllment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Jennifer Marie Dawson, September 1995 MASTER OF ARTS (1995) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow: Working as a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory AUTHOR: Jennifer Marie Dawson, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Wayne Warry NUMBER OF PAGES: iv, 264 11 ABSTRACT The experience of a service provider living and working in Moosonee and Moose Factory is largely determined by whether the individual is Cree and from these communities, or is non-Native and from "the south". This study examines these experiences in terms of stress and coping, loosely adopting and occasionally critiquing Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) definitions of these concepts. The cultural and historical factors which influence stress and coping are emphasized without denying the importance of contemporary circumstances in these politically and socially turbulent communities. Non-Native or "southern" service providers are outsiders. They are kept at a distance both by their own interpretation of and reaction to "difference" and by others who are suspicious of their motivations and commitment. Some cope with their outsider status by reinforcing it; they withdraw from active personal and professional participation in community. But instead of refusing to change and clinging desperately to what is familiar, those southerners who have remained the longest in these northern locales are willing to acknowledge the relevance and rewards of different ways of living and working. -

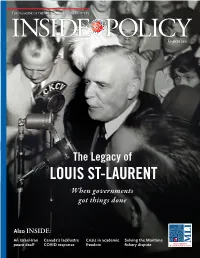

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D

ARCTIC VOL. 56, NO. 2 (JUNE 2003) P. 159–167 Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D. SHORTHOUSE,1 HENRI GOULET2 and DAVID P. SHORTHOUSE3 (Received 22 November 2001; accepted in revised form 19 August 2002) ABSTRACT. A brief collecting trip to Fort Severn, Ontario (55˚59' N, 87˚38' W), in May 2001 revealed galls of three species of cynipid wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) on the wild rose Rosa acicularis. Roses and cynipid galls occur along the banks of the Severn River above the tree line because of clay deposits, heat, and rafts of vegetation carried north by the river. Ground beetles and spiders were collected with pitfall traps. Our identification of 15 species of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae), two of them new records for Ontario, and 11 species of ground spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae), all new records for northwestern Ontario, indicates that the invertebrate fauna in the area has been poorly studied. Roads and trails away from Fort Severn, regularly scheduled airline service, and convenient accommodations make the area ideal for biological studies. Key words: cynipid galls, wild roses, ground beetles, ground-dwelling spiders, Fort Severn RÉSUMÉ. Une brève sortie de prélèvement à Fort Severn, en Ontario (55˚ 59' de lat. N., 87˚ 38' de long. O.), effectuée en mai 2001 a révélé l’existence de galles de trois espèces de cynips du rosier (hyménoptères: cynipidés) sur le rosier aciculaire Rosa acicularis. On trouve ce dernier et les galles du rosier le long des rives de la Severn au-dessus de la limite forestière en raison des dépôts d’argile, de la chaleur et de la végétation flottante que transporte la rivière en direction du Nord.