The Fiddlers of James Bay: Transatlantic Flows and Musical Indigenization Among the James Bay Cree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Institutions

Ministry of Government Services Information Access & Privacy Directory of Institutions What is the Directory of Institutions? The Directory of Institutions lists and provides contact information for: • Ontario government ministries, agencies, community colleges and universities covered by FIPPA • Municipalities and other local public sector organizations such as school boards, library boards and police services covered by MFIPPA These organizations are all called "institutions" under the Acts. The address of the FIPPA or MFIPPA Coordinator for each institution is provided to assist you in directing requests for information to the correct place. FIPPA Coordinators • Provincial Ministries • Provincial Agencies, Boards and Commissions • Colleges and Universities • Hospitals MFIPPA Coordinators • Boards of Health • Community Development Corporations • Conservation Authorities • Entertainment Boards • District Social Services Administration Boards • Local Housing Corporations • Local Roads Boards • Local Services Boards • Municipal Corporations • Planning Boards • Police Service Boards • Public Library Boards • School Boards • Transit Commissions FIPPA Coordinators Provincial Ministries MINISTRY OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 160 Bloor Street East, 4th Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2E6 Phone: 416-326-4740 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 2nd Floor NW, 1 Stone Rd. W. Guelph, ON N1G 4Y2 Phone: 519-826-3100 ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator 134 Ian Macdonald Blvd Toronto, ON M7A 2C5 Phone: 416-327-1563 MINISTRY OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator McMurty-Scott Building 5th Floor, 720 Bay St. Toronto, ON M5G 2K1 Phone: 416-326-4305 CABINET OFFICE Freedom of Information and Privacy Coordinator Whitney Block, Room 4500 99 Wellesley St. -

Amos Yong Complete Curriculum Vitae

Y o n g C V | 1 AMOS YONG COMPLETE CURRICULUM VITAE Table of Contents PERSONAL & PROFESSIONAL DATA ..................................................................................... 2 Education ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Academic & Administrative Positions & Other Employment .................................................................... 3 Visiting Professorships & Fellowships ....................................................................................................... 3 Memberships & Certifications ................................................................................................................... 3 PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Monographs/Books – and Reviews Thereof.............................................................................................. 4 Edited Volumes – and Reviews Thereof .................................................................................................. 11 Co-edited Book Series .............................................................................................................................. 16 Missiological Engagements: Church, Theology and Culture in Global Contexts (IVP Academic) – with Scott W. Sunquist and John R. Franke ................................................................................................ -

Intersections of Internationalization and Indigenization a Dissertation

Complicating International Education: Intersections of Internationalization and Indigenization A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Theresa Heath IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Christopher Johnstone, Advisor November 2019 Ó Theresa Anne Heath, 2019 Acknowledgements As is often said, a PhD program is not completed alone. There are many people who have lent guidance, patience, encouragement, and support throughout this experience. I am so grateful to have walked this road with so many excellent friends, family and colleagues. First to my family and in particular my parents, Steve and Ruth Heath. You have always supported me in every endeavor and have encouraged me to take on new challenges. This journey was no different. Thank you for your patience, your love, and unwavering faith in me. To my brothers, Christopher, Peter and Michael and my dear sisters-in-law, Linda and Jill, who have encouraged and teased me with equal measure while always having my back. To my nieces and nephews: Alexander, Kylie, McKinley, Stella, Amelia, Lilli and Lincoln. You are such bright lights. Much love to you all. To Felipe, who never doubts I can do anything and always supports me in my work and my passions, thank you. Much gratitude to my advisor, Christopher Johnstone, for your encouraging and insightful feedback and generosity of time as I worked to find my way in my research and writing. Big thanks to my committee members, Elizabeth Sumida Huaman, Peter Demerath, and Barbara Kappler, for your enthusiasm and wise words. -

Working As a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow

WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY HERE TO STAY, GONE TOMORROW: WORKING AS A SERVICE PROVIDER IN MOOSONEE AND MOOSE FACTORY By JENNIFER MARIE DAWSON, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial FulfIllment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Jennifer Marie Dawson, September 1995 MASTER OF ARTS (1995) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Here to Stay, Gone Tomorrow: Working as a Service Provider in Moosonee and Moose Factory AUTHOR: Jennifer Marie Dawson, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Wayne Warry NUMBER OF PAGES: iv, 264 11 ABSTRACT The experience of a service provider living and working in Moosonee and Moose Factory is largely determined by whether the individual is Cree and from these communities, or is non-Native and from "the south". This study examines these experiences in terms of stress and coping, loosely adopting and occasionally critiquing Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) definitions of these concepts. The cultural and historical factors which influence stress and coping are emphasized without denying the importance of contemporary circumstances in these politically and socially turbulent communities. Non-Native or "southern" service providers are outsiders. They are kept at a distance both by their own interpretation of and reaction to "difference" and by others who are suspicious of their motivations and commitment. Some cope with their outsider status by reinforcing it; they withdraw from active personal and professional participation in community. But instead of refusing to change and clinging desperately to what is familiar, those southerners who have remained the longest in these northern locales are willing to acknowledge the relevance and rewards of different ways of living and working. -

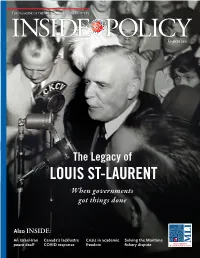

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D

ARCTIC VOL. 56, NO. 2 (JUNE 2003) P. 159–167 Notes on Cynipid Galls, Ground Beetles and Ground-Dwelling Spiders Collected at Fort Severn, Ontario JOSEPH D. SHORTHOUSE,1 HENRI GOULET2 and DAVID P. SHORTHOUSE3 (Received 22 November 2001; accepted in revised form 19 August 2002) ABSTRACT. A brief collecting trip to Fort Severn, Ontario (55˚59' N, 87˚38' W), in May 2001 revealed galls of three species of cynipid wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) on the wild rose Rosa acicularis. Roses and cynipid galls occur along the banks of the Severn River above the tree line because of clay deposits, heat, and rafts of vegetation carried north by the river. Ground beetles and spiders were collected with pitfall traps. Our identification of 15 species of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae), two of them new records for Ontario, and 11 species of ground spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae), all new records for northwestern Ontario, indicates that the invertebrate fauna in the area has been poorly studied. Roads and trails away from Fort Severn, regularly scheduled airline service, and convenient accommodations make the area ideal for biological studies. Key words: cynipid galls, wild roses, ground beetles, ground-dwelling spiders, Fort Severn RÉSUMÉ. Une brève sortie de prélèvement à Fort Severn, en Ontario (55˚ 59' de lat. N., 87˚ 38' de long. O.), effectuée en mai 2001 a révélé l’existence de galles de trois espèces de cynips du rosier (hyménoptères: cynipidés) sur le rosier aciculaire Rosa acicularis. On trouve ce dernier et les galles du rosier le long des rives de la Severn au-dessus de la limite forestière en raison des dépôts d’argile, de la chaleur et de la végétation flottante que transporte la rivière en direction du Nord. -

An Introductory History of Soviet Uzbek Academics 1924-1960

Sevket Akyildiz Sevket Akyildiz AN INTRODUCTORY HISTORY OF SOVIET UZBEK ACADEMICS 1924-1960 INTRODUCTION It took approximately 36 years (from 1924 to 1960) to establish from scratch the Soviet Central Asian academics in Uzbekistan. The investment, organization and political commitment shown by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU, est. 1925) in the predominately Muslim region of Central Asia resulted in a highly literate and educated local population. Indeed, by the 1960s, education provision in Soviet Central Asia surpassed that found in most of the socialist and non-socialist ‘Muslim majority’ countries of Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe.i In this paper I will clarify the story of the local academics in the Central Asian republic with the largest population: the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan (est. 1924). I will describe the origins of the Soviet academics and explain how they were educated, groomed and promoted by the CPSU for specific ideological, economic and cultural purposes between 1924 and 1960.1 During the historical period covered by this paper most academics employed in Uzbekistan were ethnic Slavs, Tatars or Jews. However, I will focus upon the emergence, development and integration of ethnic Uzbek academics into the higher education system during Stalin’s rule (a period when dissenting voices were purged from society) and in the decade following his death in 1953. I feel a study of the Soviet Central Asian academics is necessary because in Western literature there are some grey areas in the knowledge about the creation of local academic cadres from ‘working class’ origins in Soviet Central Asia. -

Quad Plus: Special Issue of the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs

The Journal of JIPA Indo-Pacific Affairs Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Charles Q. Brown, Jr., USAF Chief of Space Operations, US Space Force Gen John W. Raymond, USSF Commander, Air Education and Training Command Lt Gen Marshall B. Webb, USAF Commander and President, Air University Lt Gen James B. Hecker, USAF Director, Air University Academic Services Dr. Mehmed Ali Director, Air University Press Maj Richard T. Harrison, USAF Chief of Professional Journals Maj Richard T. Harrison, USAF Editorial Staff Dr. Ernest Gunasekara-Rockwell, Editor Luyang Yuan, Editorial Assistant Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator Megan N. Hoehn, Print Specialist Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs ( JIPA) 600 Chennault Circle Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6010 e-mail: [email protected] Visit Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs online at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/. ISSN 2576-5361 (Print) ISSN 2576-537X (Online) Published by the Air University Press, The Journal of Indo–Pacific Affairs ( JIPA) is a professional journal of the Department of the Air Force and a forum for worldwide dialogue regarding the Indo–Pacific region, spanning from the west coasts of the Americas to the eastern shores of Africa and covering much of Asia and all of Oceania. The journal fosters intellectual and professional development for members of the Air and Space Forces and the world’s other English-speaking militaries and informs decision makers and academicians around the globe. Articles submitted to the journal must be unclassified, nonsensitive, and releasable to the public. Features represent fully researched, thoroughly documented, and peer-reviewed scholarly articles 5,000 to 6,000 words in length. -

Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School February 2019 Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia Nevzat Torun University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Torun, Nevzat, "Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7972 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soviet Nationality Policy: Impact on Ethnic Conflict in Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Nevzat Torun A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Earl Conteh-Morgan, Ph.D. Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Date of Approval February 15, 2019 Keywords: Inter-Ethnic Conflict, Soviet Nationality Policy, Self Determination, Abkhazia, South Ossetia Copyright © 2019, Nevzat Torun DEDICATION To my wife and our little baby girl. I am so lucky to have had your love and support throughout the entire graduate experience. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Earl Conteh-Morgan, my advisor, for his thoughtful advice and comments. I would also like to thank my thesis committee- Dr. -

Ethnic Chinese Film Producers in Pre-Independence Cinema Charlotte SETIJADI Singapore Management University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School of Social Sciences School of Social Sciences 9-2010 Imagining “Indonesia”: Ethnic Chinese film producers in pre-independence cinema Charlotte SETIJADI Singapore Management University, [email protected] Thomas BARKER National University of Singapore DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/ac.21.2.25_1 Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation SETIJADI, Charlotte, & BARKER, Thomas.(2010). Imagining “Indonesia”: Ethnic Chinese film producers in pre-independence cinema. Asian Cinema, 21(2), 25-47. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/2784 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Sciences at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School of Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Asian Cinema, Volume 21, Number 2, September 2010, pp. 25-47(23) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/ac.21.2.25_1 25 Imagining “Indonesia”: Ethnic Chinese Film Producers in Pre-Independence Cinema Charlotte Setijadi-Dunn and Thomas Barker Introduction – Darah dan Doa as the Beginning of Film Nasional? In his 2009 historical anthology of filmmaking in Java 1900-1950, prominent Indonesian film historian Misbach Yusa Biran writes that although production of locally made films began in 1926 and continued until 1949, these films were not based on national consciousness and therefore could not yet be called Indonesian films. -

Audience Westernisation As a Threat to the Indigenization Model of Media Broadcast in Nigeria

Vol. 6(8), pp. 121-129, August 2014 DOI: 10.5897/JMCS2014.0400 Article Number: 8F5EE0546717 Journal of Media and Communication Studies ISSN 2141-2545 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JMCS Review Audience westernisation as a threat to the indigenization model of media broadcast in Nigeria Endong Floribert Patrick Department of Theatre and Media Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. Received 30 April 2014, Accepted 10 July 2014 Based on semi-structure interviews and secondary data, this paper examines the westernization of audiences - among other phenomena - as a serious challenge to the indigenization paradigm in Nigeria in particular and Africa as a whole. It pragmatically argues that this westernization of local audiences theoretically implies the shaping of media output (programming) according to audience interest which, unarguably, is progressively in favor of foreign content. Though commending the indigenization model – for representing a pertinent strategy for curbing the rampaging awful effects of cultural/media imperialism -, the paper argues that the “cloning” of Nigerian audiences into westerners theoretically calls for the instauration of a model of programming that is rather more inclined to heavy foreign media content. This is in line with the fact that, in principle, audience interest is a more cardinal and decisive factor in shaping media content and programming. The paper goes further to recommend moves towards “de-westernizing” and “(re)enculturating” Nigerian audiences. These moves would consist of a network of well planned cultural activities involving other influential social institutions such as religious and education institutions and the family. Through these activities Nigerian audiences may be sensitized to the necessity of conserving their authentic cultural identity (their “Nigerianness”/ “Nigerianity”) and resist their “cloning” into westerners or Americans. -

Westernisation

WESTERNISATION-INDIGENISATION IN SOCIAL WORK EDUCATION AND PRACTICE: UNDERSTANDING INDIGENISATION IN INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL WORK by Somnoma Valerie Ouedraogo and Barbara Wedler ABSTRACT International social work is about thinking globally when acting locally and vice-versa. Most of all, it is a field that requires acknowledging differences and a ‘welcoming’ of theories and practice models of one’s own singularity (cultural, political, economic) for direction in understanding social work. These context- and population-specific approaches build the core identity of the social work pro- fession. However, limited opportunity for these specific approaches, along with knowledge and skill gaps, underscore International Social Work post-second- ary curriculum on a global scale. Thus, the authors are centrally concerned with conducting a research-informed study to strengthen International Social Work courses. In this article, the authors outline the development of Indigenisation theory and offer ways of thinking and interacting with social work concepts and methodologies in an International Social Work teaching and learning context. This article offers a pragmatic approach of considering a dialectic of Westernisa- tion-Indigenisation, to connect the local and the global as well as the North and the South by aiming to develop the concept of Indigenisation in International Social Work. Through a tri-continental partnership (Europe, North America, Africa), the authors outline their current and future plans to create a research study to develop curriculum and conduct field work, to focus efforts on decol- onizing social work practice and education. This partnership offers a two-direc- tional relationship between global thinking and local acting, therefore modelling Indigenisation theory and its application on an international scale.