The Peasant's Banquet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

The Turing Test

THE TURING TEST Nick Totton It is within language that the world speaks to us in a voice that is not our own. This is, I believe, a first and fundamental experience of dictation and correspondence - the dead speaking to us in language is only one level of the outside that ceaselessly invades our thought. (Robin Blaser, The Practice of Outside) This sort of thing is more difficult to do than it looked. (Professor A.W. Verrall, posthumously) Dead Authors In the early years of the twentieth century an unusual literary project was initiated, which continued for over thirty years: a project known generally as the 'Cross Correspondences': a collaboration between a number of authors and/or transcribers, some of them friends and relatives, others complete strangers, and in widely varying circumstances. These variations include important factors like class and education; but most striking, perhaps, is that several of the more prominent figures involved were dead at the time. The project1 consists of a number of separate texts, no one or several of which contains the work itself. The work - like the structure of a myth - emerges solely from the relationship between these different texts: it is a second-order reality, an epiphenomenon. One could appropriately say that the work itself is incarnate in the texts, though identifiable with none of them, nor yet with the sum of the parts. In one sense the Cross Correspondences are very much of their time: a strikingly Modernist texture, inhabiting the same world as Joyce and Eliot, as a small sample of the enormous material will show: Lots of wars - A Siege I hear the sound of chipping. -

C O M M E N T a T I O N

COMMENTATIONES Eos C 2013 ISSN 0012-7825 SICILY’S PLACE IN GREEK POETRY* by GERSON SCHADE ...vuote le mani, ma pieni gli occhi del ricordo di lei... Ibn Hamdis ABSTRACT: A multitude of literary texts dealing with Sicily are presented in four chapters. Starting with a fusion of the Aeneid’s presentation of Sicily and some modern literary associations, the opening chapter proves that in Virgil’s usage the term “Sicilian” became a kind of shibboleth, which turns his works into texts au deuxième degré. His Sicelides Musae come from Theocritus whose poetry is at the centre of the bifold second chapter, offering two retrospective glances upon earlier Greek poetry: a first half is dedicated to Theocritus’ Cyclops-poems and their ‘bucolic archae- ology’. Quite similarly, the second half of the second chapter is concerned with Theocritus’ poem on Hieron II and its epinician predecessors, i.e. Simonides and Pindar. This tradition, however, might well have started earlier than Simonides, and it is not unlikely that already Ibykos and Stesichoros, the latter born in Sicily, composed epinician poetry. Pindar and Simonides’ nephew Bakchylides were guests of Hieron I, who also invited innovative Aeschylus, reputed to be a vir utique Siculus, to whom the third chapter is dedicated. Aside from the bucolic and epinician tradition, Sicily has another literary facet of which the fourth chapter catches some glimpses: Sicilian lifestyle attracted attention, and Sicilians were famous in antiquity for some extravagancies, a fact well known to comedy one streak of which is supposed to have its origins in Sicily. Sicilian food and all what comes with it were not altogether above suspicion, as Plato and his translator Cicero remarked, and also Horace thought of Sicilian banquets, Siculae dapes, as most lavish. -

Cratinus' Cyclops

S. Douglas Olson Cratinus’ Cyclops – and Others Abstract The primary topic of this paper is Cratinus’ lost Odusseis (“Odysseus and his Companions”), in particular fr. 147, and the over-arching question of what can reasonably be called “Cyclops-plays”. My larger purpose is to argue for caution in regard to what we can and cannot regard as settled about the basic dramatic arc or “storyline” of individual lost comedies, while simultaneously advocating openness to a larger set of possibilities than is sometimes allowed for. Late 5 th -century comedy seems to have been fundamentally dependent on wild acts of imagination and fantastic re- workings of traditional material. Given how little we know about most authors and plays, we must accordingly both beware of over-confidence in our reconstructions and attempt to not too aggressively box in the impulses of the genre. As an initial way of illustrating and articulating these issues, I begin not with Cratinus but with the five surviving fragments of Nicophon’s Birth of Aphrodite. Temi principali di questo contributo sono i perduti Odissei (Odisseo e i suoi compagni ) di Cratino, in particolare il fr. 147, e la più complessiva questione di quali commedie possano essere ragionevolmente definite “commedie sul Ciclope”. Il mio scopo più ampio è di indurre alla prudenza rispetto a cosa possiamo e non possiamo ritenere stabilito riguardo alla struttura drammaturgica di fondo o alla “trama” di singole commedie perdute, e al contempo incoraggiare l’apertura verso uno spettro di possibilità più ampio rispetto a quanto talvolta non sia consentito. La commedia di fine quinto secolo sembra esser stata ispirata fondamentalmente da liberi atti di sfrenata immaginazione e da riscritture fantastiche di materiale tradizionale. -

The Ear of Dionysius; but the Name Only Dates from the Sixteenth Century

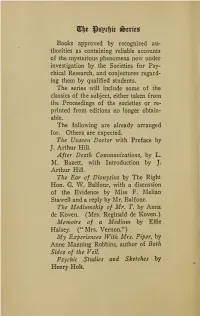

an&e $*?t&fc Series; Books approved by recognized au- thorities as containing reliable accounts of the mysterious phenomena now under investigation by the Societies for Psy- chical Research, and conjectures regard- ing them by qualified students. The series will include some of the classics of the subject, either taken from the Proceedings of the societies or re- printed from editions no longer obtain- able. The following are already arranged for. Others are expected. The Unseen Doctor with Preface by J. Arthur Hill. After Death Communications, by L. M. Bazett, with Introduction by J. Arthur Hill. The Ear of Dionysius by The Right Hon. G. W. Balfour, with a discussion of the Evidence by Miss F. Melian Stawell and a reply by Mr. Balfour. The Mediamship of Mr. T. by Anna de Koven. (Mrs. Reginald de Koven.) Memoirs of a Medium by Erne Halsey. (" Mrs. Vernon.") My Experiences With Mrs. Piper, by Anne Manning Robbins, author of Both Sides of the Veil. Psychic Studies and Sketches by Henry Holt. THE EAR OF DIONYSIUS FARTHER SCRIPTS AFFORDING EVIDENCE OF PERSONAL SURVIVAL BY THE RIGHT HON. G. W. BALFOUR WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVIDENCE BY MISS F. MELIAN SHAWELL AND A REPLY BY MR. BALFOUR Reprinted by authority from the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1920 y*>0\ Copyright 1920 BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY / /7 $ ©CI.A604043 CONTENTS PART I PAGE Scripts Affording Evidence of Personal Survival 3 Appendix 67 PART II Discussion of the Evidence JJ A Paper Read to the Society of Psychical Research by Miss F. -

I UNIVERSITÉ PARIS IV

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS IV - SORBONNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE MONDES ANCIENS ET MEDIEVAUX |__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__| (N° d !enregistrement attribué par la bibliothèque) T H È S E pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L'UNIVERSITÉ PARIS IV Discipline : Lettres Classiques présentée et soutenue publiquement par Pauline Anaïs LeVen le 25 novembre 2008 LES NOUVEAUX VISAGES DE LA MUSE AU IVe SIÈCLE AV. J.-C. (THE MANY-HEADED MUSE: TRADITION AND INNOVATION IN FOURTH-CENTURY B.C. GREEK LYRIC POETRY) Co-directeurs de thèse: Monique Trédé et Andrew Ford Jury: M. Claude Calame M. Eric Csapo M. Paul Demont M. Dider Pralon i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents iii Acknowledgments v Introduction 1 Chapter 1 A collection of Unrecollected Authors? 13 1. The corpus 14 2. The methods 35 Chapter 2 New Music and its Myths 43 1. Revisiting newness 43 2. New Music from the top 63 Chapter 3 Poet and Society: the “lives” of fourth-century poets 91 1. Mousikê and middlenesss 94 2. Opsophagia and philo -xenia 103 3. Poetry and parrhêsia 115 Chapter 4 Poetics of Late-Classical Lyric 137 1. Stylistic innovations 139 2. Thematic features 164 3. A case-study: Philoxenus’ Cyclops or Galatea 190 Chapter 5 Sympotica: Genre, Deixis and Performance 203 1. Changing sympotic practices 204 2. Nouvelle cuisine and New Dithyramb 213 3. Deixis and performance context in Ariphron’s paean 231 4. Aristotle’s hymn to Hermias 239 Chapter 6 A canon set in stone? 250 1. The new classic: Aristonous 258 2. -

The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology

— Early Castles of Stone — 1111 2 3 4 5 THE ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK 6 OF GREEK MYTHOLOGY 7 8 ᇹᇺᇹ 9 11110 11 12 13 14 11115 16 17 18 19 11120 21 22 23 24 25111 26 27 28 29 11130 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 11140 41 42 43 44 45 11146 1111 2 3 4 5 THE ROUTLEDGE 6 7 HANDBOOK OF GREEK 8 9 11110 MYTHOLOGY 11 ᇹᇺᇹ 12 13 14 11115 Based on 16 17 H.J. Rose’s Handbook of 18 Greek Mythology 19 11120 21 22 23 24 25111 Robin Hard 26 27 28 29 11130 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 11140 41 42 43 44 45 11146 First published 2004 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 2004 Robin Hard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record has been requested for this title ISBN 0-203-44633-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-75457-3 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0–415–18636–6 (Print Edition) 1111 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11110 11 12 13 14 11115 In Memory of 16 LAUNCELOT FREDERIC HARD 17 18 1916–2002 19 11120 21 -

Index Locorum

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01853-2 - The Many-Headed Muse: Tradition and Innovation in Late Classical Greek Lyric Poetry Pauline A. Leven Index More information Index locorum Achaeus Anaxandrides TGrF ii F26, 222 fr. 18 KA (Treasure), 273 Aelian fr. 42 KA (Protesilaus), 250 Varia Historia 10.18, 229 Anonymous Aeschylus Erythraean Paean (ed. Powell 1925), Agamemnon 1056, 298 286–94, 326 Choephoroe PMG 848, 53 49–53, 216 PMG 863, 96 827–30, 325 PMG 865, 96 1035, 298 PMG 867, 271 Eumenides PMG 871.6–7, 306 180, 298 PMG 890, 273–4, 279 201, 96 PMG 900, 48, 260 Persae (ed. Hall 1996) PMG 925, 39 69–72, 183, 206 PMG 926, 40, 61 71, 183 PMG 927, 40 266–7, 196 PMG 928, 40 392, 196 PMG 929, 39 397, 208 PMG 929a, 227 429–30, 196–7 PMG 929b, 61 466–7, 203 PMG 929g, 228 574, 96 PMG 929h, 228 744, 206 PMG 939.16–17, 179 747–8, 206 PMG 962, 156 1054, 210 PMG 963, 156 Supplices 1018–73, 325 PMG 1006, 156 TGrF iii fr. 143 (Mysians), 210 PMG 1019, 272 TGrF iii fr. 150 (Nereides), 181 PMG 1027, 43 Alcaeus TGrF ii F1e (Argo), 223 fr. 69.7 Voigt, 102 TGrF ii F1f (Atlas), 223 fr. 345.2 Voigt, 102 TGrF ii F5a (Cresus?), 225 Alcman TGrF ii F8f (Persai), 225 PMG 1.66, 102 TGrF ii F8h (Persephone), 223 PMG 98, 278 TGrF ii F178, 307 Alexis TGrF ii F327c (Mysoi?), 225 fr. 37–40 KA (Cyclops), 233 TGrF ii F664 (Gyges), 225 fr. -

Frances Pownall, Dionysius I and the Creation of a New-Style Macedonian Monarchy

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-ONE: 2017 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe òJoseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 31 (2017) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-one Numbers 1-2 1 Paul Johstono, Rumor, Rage, and Reversal: Tragic Patterns in Polybius’ Account of Agathocles at Alexandria 21 Frances Pownall, Dionysius I and the Creation of a New-Style Macedonian Monarchy 39 Christopher Kegerreis, Setting a Royal Pace: Achaemenid Kingship and the Origin of Alexander the Great’s Bematistai 65 Waldemar Heckel, Dareios III’s Military Reforms Before Gaugamela and the Alexander Mosaic: A Note NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Choruses for Dionysus: Studies in the History of Dithyramb and Tragedy by Matthew C. Wellenbach B.A., Williams College, 2009

Choruses for Dionysus: Studies in the History of Dithyramb and Tragedy By Matthew C. Wellenbach B.A., Williams College, 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Matthew C. Wellenbach This dissertation by Matthew C. Wellenbach is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date________________ _______________________________________ Johanna Hanink, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date________________ _______________________________________ Deborah Boedeker, Reader Date_______________ _______________________________________ Pura Nieto Hernández, Reader Date_______________ _______________________________________ Andrew Ford, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ _______________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Matthew C. Wellenbach was born on June 4, 1987, in Philadelphia, PA. He first began studying Latin during his primary and second education, and in 2009 he earned a B.A. in Classics, magna cum laude, and with highest honors, from Williams College, located in Williamstown, MA. In the fall of 2008, he was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. He matriculated at Brown University in Providence, RI, in the fall of 2009 as a graduate student in the Department of Classics. During his time at Brown, he presented a paper on similes in the Odyssey at the 2012 meeting of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South and published a review of a monograph on Aeschylus’ Suppliant Women in Bryn Mawr Classical Review as well as an article on depictions of choral performance in Attic vase-paintings in Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies. -

Diogenes of Babylon: a Stoic on Music and Ethics

Diogenes of Babylon: A Stoic on Music and Ethics Linda Helen Woodward UCL Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Classics 1 Diogenes of Babylon: A Stoic on Music and Ethics I, Linda Helen Woodward, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to analyse Diogenes of Babylon's musico-ethical theories, to place them into their historical context, and to examine the possible influences on his thought. Earlier treatments of this Stoic's work have been hampered by the lacunose state of Philodemus' surviving text, the major source, and in some cases an opponent's views have been mistakenly attributed to Diogenes. Conversely, the state of the text together with erroneous column numbering, have resulted in part of Diogenes' philosophy being ascribed to his Epicurean opponent. Taking Professor Delattre's recently reconstructed edition of Philodemus’ De musica as my starting point, I attempt to more fully analyse Diogenes' theory of music and ethics. Following a short introductory chapter, I briefly examine Diogenes' other interests, analyse his psychology compared with that of earlier Stoics, and examine how that fits into Diogenes' view on music in education. I outline Diogenes' general view on music, and compare the musical writings of Plato, Aristotle and the early Peripatetics with those of Diogenes, particularly in relation to education, and outline areas that might have influenced the Stoic. I also look at later writings where they can be seen as evidence for Diogenes' work. -

Theocritus' Pharmacy: Poetry As Self-Care in the Idylls

Theocritus’ Pharmacy: Poetry as Self-Care in the Idylls by Edwin Coulter Ward IV B.A. University of Mississippi, 2016 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Classics 2019 ii This thesis entitled: Theocritus’ Pharmacy: Poetry as Self-Care in the Idylls written by Edwin Coulter Ward IV has been approved for the Department of Classics ______________________ Yvona Trnka-Amrhein ______________________ John Gibert ______________________ Laurialan Reitzammer Date:_____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above-mentioned discipline. iii Ward, Edwin Coulter (M.A., Classics) Theocritus’ Pharmacy: Poetry as Self-Care in the Idylls Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Yvona Trnka-Amrhein Throughout the Idylls of Theocritus there are references to the curative properties of poetry and song. In Idyll 11, the poet states that “there is no remedy (pharmakon) for love other than the Pierian Muses” (Id. 11.1-2). This thesis explores the consequences of this claim for the poem as a whole and argues that the poem’s main character, Polyphemus the Cyclops, does achieve an alleviation of the symptoms of lovesickness. The first chapter contextualizes the Cyclops’ recovery in relation to other versions of his character in the Greek literary tradition and within the framework of contemporary medical practice. Chapter two deals with a similar story of lovesickness and song.