C O M M E N T a T I O N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Kathryn Mattison, Reviewing K. Bosher, Ed., Theater Outside Athens

K. Bosher, ed., Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. Pp. xvii + 473: ISBN: 978-0521761789. *It was with deep sadness that I learned of Kathryn Bosher’s recent death. I submit this review as a tribute to a gifted scholar and offer my condolences to her family and friends. Theater Outside Athens attempts to understand how theater was produced in Sicily and South Italy and what its relationship with Athenian theater was. It outlines a complex relationship between Sicilian and Athenian theater but also touches on issues such as colonization and the dynamics between the Sicilian tyrannies and Athenian democracy. The result of such breadth is a deeply engaging volume that will certainly inspire a continuing dialogue on the important contributions of the Sicilian poets and practitioners. The volume itself is well-organized, and for the most part the chapters complement each other nicely. One might always lament the lack of dialogue between chapters in such a volume, but the broad scope and overall quality of the chapters make it seem like a trivial point in this case. Bosher’s introduction presents many of the difficulties inherent in this topic, including vastly divergent views and a lack of clear evidence in many fields, and leaves the reader feeling primed for the following chapters. Even one not already immersed in Sicilian history and culture is left with a sense of the problems and a curiosity about how the chapters might address them. The volume is then divided into three parts. Part I (“Tyrants, texts, and theater in early Sicily”) begins with Jonathan M. -

Devising Descent Mime, Katabasis and Ritual in Theocritus' Idyll 15 Hans Jorgen Hansen a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Th

Devising Descent Mime, Katabasis and Ritual in Theocritus’ Idyll 15 Hans Jorgen Hansen A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. William H. Race Dr. Owen Goslin Dr. Werner Riess Abstract Hans Jorgen Hansen: Devising Descent: Mime, Katabasis and Ritual in Theocritus’ Idyll 15 (Under the direction of Dr. William H. Race) In this thesis I investigate the genres and structure of Theocritus’ fifteenth Idyll, as well as its katabatic and ritual themes. Though often considered an urban mime, only the first 43 lines exhibit the formal qualities of mime found in Herodas’ Mimiambi, the only other surviving corpus of Hellenistic mime. The counterpoint to the mimic first section is the Adonia that makes up the last section of the poem and amounts to an urban recasting of pastoral poetry. A polyphonic, katabatic journey bridges the mimic and pastoral sections and is composed of four encounters that correspond to ordeals found in ritual katabases. The structure of the poem is then tripartite, beginning in the profane world of the household mime, progressing through the liminal space of the streets and ending in the sacred world of the Adonia. This progression mirrors Theocritus’ evolution from Syracusan mimic poet to Alexandrian pastoral poet. ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Mime and Structure in the Adoniazusae 6 1.1: Introduction 6 1.2.1: The Formal Features of Herodas’ Poetry 12 1.2.2: Homophony and Herodas’ Fourth Mimiamb 21 1.3.1: Theocritus’ Household-Mime 26 1.3.2: The Streets of Alexandria and Theocritus’ Polyphonic Mime 32 1.4: Conclusion 41 Chapter 2: Katabasis and Ritual in the Adoniazusae 44 2.1: Introduction 44 2.2: The Katabatic Structure, Characters and Imagery of Theoc. -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

Fish Lists in the Wilderness

FISH LISTS IN THE WILDERNESS: The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree Author(s): Ephraim Lytle Source: Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April-June 2010), pp. 253-303 Published by: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40835487 . Accessed: 18/03/2014 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 71.168.218.10 on Tue, 18 Mar 2014 10:14:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HESPERIA 79 (2OIO) FISH LISTS IN THE Pages 253~3°3 WILDERNESS The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree ABSTRACT This articlepresents a newtext and detailedexamination of an inscribedHel- lenisticdecree from the Boiotian town of Akraiphia (SEG XXXII 450) that consistschiefly of lists of fresh- and saltwaterfish accompanied by prices. The textincorporates improved readings and restoresthe final eight lines of the document,omitted in previouseditions. -

The Turing Test

THE TURING TEST Nick Totton It is within language that the world speaks to us in a voice that is not our own. This is, I believe, a first and fundamental experience of dictation and correspondence - the dead speaking to us in language is only one level of the outside that ceaselessly invades our thought. (Robin Blaser, The Practice of Outside) This sort of thing is more difficult to do than it looked. (Professor A.W. Verrall, posthumously) Dead Authors In the early years of the twentieth century an unusual literary project was initiated, which continued for over thirty years: a project known generally as the 'Cross Correspondences': a collaboration between a number of authors and/or transcribers, some of them friends and relatives, others complete strangers, and in widely varying circumstances. These variations include important factors like class and education; but most striking, perhaps, is that several of the more prominent figures involved were dead at the time. The project1 consists of a number of separate texts, no one or several of which contains the work itself. The work - like the structure of a myth - emerges solely from the relationship between these different texts: it is a second-order reality, an epiphenomenon. One could appropriately say that the work itself is incarnate in the texts, though identifiable with none of them, nor yet with the sum of the parts. In one sense the Cross Correspondences are very much of their time: a strikingly Modernist texture, inhabiting the same world as Joyce and Eliot, as a small sample of the enormous material will show: Lots of wars - A Siege I hear the sound of chipping. -

Greek Religious Thought from Homer to the Age of Alexander

'The Library of Greek Thought GREEK RELIGIOUS THOUGHT FROM HOMER TO THE AGE OF ALEXANDER Edited by ERNEST BARKER, M.A., D.Litt., LL.D. Principal of King's College, University of London tl<s } prop Lt=. GREEK RELIGIOUS THOUGHT FROM HOMER TO THE AGE OF ALEXANDER BY F. M. CORNFORD, M.A. Fellow and Lecturer of Trinity College, Cambridge MCMXXIII LONDON AND TORONTO J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON tf CO. HOTTO (E f- k> ) loUr\ P. DOTTO/U TALKS ) f^op Lt=. 7 yt All rights reserved f PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN TO WALTER DE LA MARE INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is to let the English reader see for himself what the Greeks, from Homer to Aristotle, thought about the world, the gods and their relations to man, the nature and destiny of the soul, and the significance of human life. The form of presentation is prescribed by the plan of the series. The book is to be a compilation of extracts from the Greek authors, selected, so far as possible, without prejudice and translated with such honesty as a translation may have. This plan has the merit of isolating the actual thought of the Greeks in this period from all the constructions put upon it by later ages, except in so far as the choice of extracts must be governed by some scheme in the compiler's mind, which is itself determined by the limits of his knowledge and by other personal factors. In the book itself it is clearly his business to reduce the influence of these factors to the lowest point; but in the introduction it is no less his business to forewarn the reader against some of the consequences. -

The Acts of John, the Acts of Andrew and the Greek Novel

The Acts of John, the Acts of Andrew and the Greek Novel JAN N. BREMMER University of Groningen The study of the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles (henceforth: AAA) has been do- ing reasonably well in recent times. Swiss colleagues have been working for years on critical texts of the major Acts, those of John, Andrew, Peter, Paul, and Thomas. Moreover, we now have a proper journal, Apocrypha, dedicated to the apocryphal literature. Yet it is clear that there is an enormous amount of work still to be done. Until now, we have only one critical authoritative text from the Swiss équipe, that of the Acts of John; the one of the Acts of Andrew by Jean-Marc Prieur (1947-2012) has not been able to establish itself as authoritative after the blister- ing attack on its textual constitution by Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta (§ 2). Appearance of the editions of the other major texts does not seem to be in sight, however hard our Swiss colleagues have been working on them. But even with the texts as we have them, there is still much to be done: not only on the editions and contents as such, but also on their contextualisation within contemporary pagan and Christian culture. Moreover, these texts were not canonical texts whose content could be changed as little as possible, but they were transmitted in the following centuries by being supplemented, abbreviated, modified, and translated in all kinds of ways. In other words, as time went on, people will hardly have seen any difference be- tween them and other hagiographical writings celebrating the lives and, espe- cially, deaths of the Christian saints.1 It is obvious that these versions all need to be contextualised in their own period and culture. -

Cratinus' Cyclops

S. Douglas Olson Cratinus’ Cyclops – and Others Abstract The primary topic of this paper is Cratinus’ lost Odusseis (“Odysseus and his Companions”), in particular fr. 147, and the over-arching question of what can reasonably be called “Cyclops-plays”. My larger purpose is to argue for caution in regard to what we can and cannot regard as settled about the basic dramatic arc or “storyline” of individual lost comedies, while simultaneously advocating openness to a larger set of possibilities than is sometimes allowed for. Late 5 th -century comedy seems to have been fundamentally dependent on wild acts of imagination and fantastic re- workings of traditional material. Given how little we know about most authors and plays, we must accordingly both beware of over-confidence in our reconstructions and attempt to not too aggressively box in the impulses of the genre. As an initial way of illustrating and articulating these issues, I begin not with Cratinus but with the five surviving fragments of Nicophon’s Birth of Aphrodite. Temi principali di questo contributo sono i perduti Odissei (Odisseo e i suoi compagni ) di Cratino, in particolare il fr. 147, e la più complessiva questione di quali commedie possano essere ragionevolmente definite “commedie sul Ciclope”. Il mio scopo più ampio è di indurre alla prudenza rispetto a cosa possiamo e non possiamo ritenere stabilito riguardo alla struttura drammaturgica di fondo o alla “trama” di singole commedie perdute, e al contempo incoraggiare l’apertura verso uno spettro di possibilità più ampio rispetto a quanto talvolta non sia consentito. La commedia di fine quinto secolo sembra esser stata ispirata fondamentalmente da liberi atti di sfrenata immaginazione e da riscritture fantastiche di materiale tradizionale. -

Alexandrea Ad Aegyptvm the Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity

Alexandrea ad aegyptvm the legacy of multiculturalism in antiquity editors rogério sousa maria do céu fialho mona haggag nuno simões rodrigues Título: Alexandrea ad Aegyptum – The Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity Coord.: Rogério Sousa, Maria do Céu Fialho, Mona Haggag e Nuno Simões Rodrigues Design gráfico: Helena Lobo Design | www.hldesign.pt Revisão: Paula Montes Leal Inês Nemésio Obra sujeita a revisão científica Comissão científica: Alberto Bernabé, Universidade Complutense de Madrid; André Chevitarese, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; Aurélio Pérez Jiménez, Universidade de Málaga; Carmen Leal Soares, Universidade de Coimbra; Fábio Souza Lessa, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; José Augusto Ramos, Universidade de Lisboa; José Luís Brandão, Universidade de Coimbra; Natália Bebiano Providência e Costa, Universidade de Coimbra; Richard McKirahan, Pomona College, Claremont Co-edição: CITCEM – Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar «Cultura, Espaço e Memória» Via Panorâmica, s/n | 4150-564 Porto | www.citcem.org | [email protected] CECH – Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Humanísticos | Largo da Porta Férrea, Universidade de Coimbra Alexandria University | Cornice Avenue, Shabty, Alexandria Edições Afrontamento , Lda. | Rua Costa Cabral, 859 | 4200-225 Porto www.edicoesafrontamento.pt | [email protected] N.º edição: 1152 ISBN: 978-972-36-1336-0 (Edições Afrontamento) ISBN: 978-989-8351-25-8 (CITCEM) ISBN: 978-989-721-53-2 (CECH) Depósito legal: 366115/13 Impressão e acabamento: Rainho & Neves Lda. | Santa Maria da Feira [email protected] Distribuição: Companhia das Artes – Livros e Distribuição, Lda. [email protected] Este trabalho é financiado por Fundos Nacionais através da FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto PEst-OE/HIS/UI4059/2011 contents PREFACE Gabriele Cornelli 5 MOVING FORWARD Ismail Serageldin 9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 13 INTRODUCTION 15 PART I: ALEXANDRIA, A CITY OF MANY FACES 19 On the Trail of Alexandria’s Founding Maria de Fátima Silva 20 The Ptolemies: An Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. -

The Ear of Dionysius; but the Name Only Dates from the Sixteenth Century

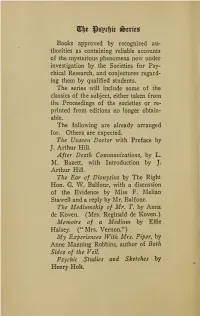

an&e $*?t&fc Series; Books approved by recognized au- thorities as containing reliable accounts of the mysterious phenomena now under investigation by the Societies for Psy- chical Research, and conjectures regard- ing them by qualified students. The series will include some of the classics of the subject, either taken from the Proceedings of the societies or re- printed from editions no longer obtain- able. The following are already arranged for. Others are expected. The Unseen Doctor with Preface by J. Arthur Hill. After Death Communications, by L. M. Bazett, with Introduction by J. Arthur Hill. The Ear of Dionysius by The Right Hon. G. W. Balfour, with a discussion of the Evidence by Miss F. Melian Stawell and a reply by Mr. Balfour. The Mediamship of Mr. T. by Anna de Koven. (Mrs. Reginald de Koven.) Memoirs of a Medium by Erne Halsey. (" Mrs. Vernon.") My Experiences With Mrs. Piper, by Anne Manning Robbins, author of Both Sides of the Veil. Psychic Studies and Sketches by Henry Holt. THE EAR OF DIONYSIUS FARTHER SCRIPTS AFFORDING EVIDENCE OF PERSONAL SURVIVAL BY THE RIGHT HON. G. W. BALFOUR WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVIDENCE BY MISS F. MELIAN SHAWELL AND A REPLY BY MR. BALFOUR Reprinted by authority from the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1920 y*>0\ Copyright 1920 BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY / /7 $ ©CI.A604043 CONTENTS PART I PAGE Scripts Affording Evidence of Personal Survival 3 Appendix 67 PART II Discussion of the Evidence JJ A Paper Read to the Society of Psychical Research by Miss F. -

Copyright by Bronwen Lara Wickkiser 2003

Copyright by Bronwen Lara Wickkiser 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Bronwen Lara Wickkiser certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Appeal of Asklepios and the Politics of Healing in the Greco-Roman World Committee: _________________________________ Lesley Dean-Jones, Supervisor _________________________________ Erwin Cook _________________________________ Fritz Graf _________________________________ Karl Galinsky _________________________________ L. Michael White The Appeal of Asklepios and the Politics of Healing in the Greco-Roman World by Bronwen Lara Wickkiser, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My work has benefited immeasurably from the comments and suggestions of countless individuals. I am grateful to them all, and wish to mention some in particular for their extraordinary efforts on my behalf. First and foremost, Lesley Dean-Jones, whose wide-ranging expertise guided and vastly enhanced this project. Her skill, coupled with her generosity, dedication, and enthusiasm, are a model to me of academic and personal excellence. Also Erwin Cook, Karl Galinsky, and L. Michael White, unflagging members of my dissertation committee and key mentors throughout my graduate career, who have shown me how refreshing and stimulating it can be to “think outside the box.” And Fritz Graf who graciously joined my committee, and gave generously of his time and superb insight. It has been an honor to work with him. Special thanks also to Erika Simon and Jim Hankinson who encouraged this project from the beginning and who carefully read, and much improved, many chapters.