New Sappho” and “Newest Sappho”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-1983 A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur Jay Curlin Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Curlin, Jay, "A Close Look at Two Poems by Richard Wilbur" (1983). Honors Theses. 209. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CLOSE LOOK AT TWO POEMS BY RICHARD WILBUR Jay Curlin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program Ouachita Baptist University The Department of English Independent Study Project Dr. John Wink Dr. Susan Wink Dr. Herman Sandford 16 April 1983 INTRODUCTION For the past three semesters, I have had the pleasure of studying the techniques of prosody under the tutelage of Dr. John Wink. In this study, I have read a large amount of poetry and have studied several books on prosody, the most influential of which was Poetic Meter and Poetic Form by Paul Fussell. This splendid book increased vastly my knowledge of poetry. and through it and other books, I became a much more sensitive, intelligent reader of poems. The problem with my study came when I tried to decide how to in corporate what I had learned into a scholarly paper, for it seemed that any attempt.to do so would result in the mere parroting of the words of Paul Fussell and others. -

A Study of the Poetic Relationship Between Thomas Hardy and A.C

HARDY'S DANGEROUS COMPANION: A STUDY OF THE POETIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THOMAS HARDY AND A.C. SWINBURNE by EILEEN DELEHANTY PEARKES B.A. Stanford University, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER: OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1991 (c) Eileen Delehanty Pearkes, 1991 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ^MQrUtSM The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date oa- it mi DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT Thomas Hardy's elegy to A.C. Swinburne, composed in 1910 shortly after his death, points to a poetic relationship between the two poets which goes beyond admiration or influence. The relationship between Hardy and Swinburne has not been adequately explored by twentieth century critics, and it is the central purpose of this thesis to examine more closely parallels between them on the level of technique. Analysis of Hardy's elegy entitled "A Singer Asleep" suggests how Hardy may have identified with Swinburne on the level of technique. -

HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH and HISTORY in CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman

STUDIES IN CLASSICS Edited by Dirk Obbink & Andrew Dyck Oxford University/The University of California, Los Angeles A ROUTLEDGE SERIES STUDIES IN CLASSICS DIRK OBBINK & ANDREW DYCK, General Editors SINGULAR DEDICATIONS Founders and Innovators of Private Cults in Classical Greece Andrea Purvis EMPEDOCLES An Interpretation Simon Trépanier FOR SALVATION’S SAKE Provincial Loyalty, Personal Religion, and Epigraphic Production in the Roman and Late Antique Near East Jason Moralee APHRODITE AND EROS The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology Barbara Breitenberger A LINGUISTIC COMMENTARY ON LIVIUS ANDRONICUS Ivy Livingston RHETORIC IN CICERO’S PRO BALBO Kimberly Anne Barber AMBITIOSA MORS Suicide and the Self in Roman Thought and Literature Timothy Hill ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM AND THE BIRTH OF MUSICOLOGY Sophie Gibson HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH AND HISTORY IN CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman Routledge New York & London Published in 2005 by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016 http://www.routledge-ny.com/ Published in Great Britain by Routledge 2 Park Square Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN http://www.routledge.co.uk/ Copyright © 2005 by Taylor & Francis Group, a Division of T&F Informa. Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photo copying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

"Then Said the Lady Circe: 'So: All Those Trials Are Over. Listen With

5 beauty to ! woe to th( He will nc in ioy, cro the Sirens on their s~ of dead m and flayec keep well with bees should he let the m~ and {oot, so you m shout as your crex and keep What th~ and you plan the tell you, and dart roars ar. the gods Not eve i 30 lies betx piercing dissolvi to sho~ 35 NO toOl as land so shee "Then said the Lady Circe: Midwa ’So: all those trials are over. 2-3 in Circe opens t Listen with care valuable ally, In tl 40 this in lines, she describes in your rr to this, now, and a god will arm your mind. danger that he a~ Square in your ship’s path are Sirens, crying meet on their way home, would UNIT SIX PART 1: THE ODYSSEY 5 beauty to bewitch men coasting by; woe to the innocent who hears that sound! He will not see his lady nor his children in joy, crowding about him~ home from sea; the Sirens will sing his mind away 10 on their sweet meadow lolling. There are bones of dead men rotting in a pile beside them and flayed skins shrivel around the spot. 12 flayed: torn off; stripped. Steer wide; keep well to seaward; plug your oarsmen’s ears with beeswax kneaded soft; none of the rest 14 kneaded (n~’dYd): squeezed and is should hear that song. pressed. But if you wish to listen, 15-21 Circe suggests a way for Odysseus to hear the Sirens safely. -

STONEFLY NAMES from CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Perla Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 14 Autor(en)/Author(s): Ricker William E. Artikel/Article: Stonefly names from classical times 37-43 STONEFLY NAMES FROM CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker Recently I amused myself by checking the stonefly names that seem to be based on the names of real or mythological persons or localities of ancient Greece and Rome. I had copies of Bulfinch’s "Age of Fable," Graves; "Greek Myths," and an "Atlas of the Ancient World," all of which have excellent indexes; also Brown’s "Composition of Scientific Words," And I have had assistance from several colleagues. It turned out that among the stonefly names in lilies’ 1966 Katalog there are not very many that appear to be classical, although I may have failed to recognize a few. There were only 25 in all, and to get even that many I had to fudge a bit. Eleven of the names had been proposed by Edward Newman, an English student of neuropteroids who published around 1840. What follows is a list of these names and associated events or legends, giving them an entomological slant whenever possible. Greek names are given in the latinized form used by Graves, for example Lycus rather than Lykos. I have not listed descriptive words like Phasganophora (sword-bearer) unless they are also proper names. Also omitted are geographical names, no matter how ancient, if they are easily recognizable today — for example caucasica or helenica. alexanderi Hanson 1941, Leuctra. -

Aurora (Mythology)

Aurora (mythology) 2 Usage in literature and music Aurora, by Guercino, 1621-23: the ceiling fresco in the Casino Ludovisi, Rome, is a classic example of Baroque illusionistic painting Aurora (Latin: [awˈroːra]) is the Latin word for dawn, and the goddess of dawn in Roman mythology and Latin poetry. Like Greek Eos and Rigvedic Ushas (and possi- bly Germanic Ostara), Aurora continues the name of an earlier Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos. Aurora Taking Leave of Tithonus 1 Roman mythology 1704, by Francesco Solimena From Homer's Iliad: In Roman mythology, Aurora, goddess of the dawn, re- news herself every morning and flies across the sky, an- Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was has- nouncing the arrival of the sun. Her parentage was flex- tening from the streams of Okeanos, to bring ible: for Ovid, she could equally be Pallantis, signifying light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the daughter of Pallas,[1] or the daughter of Hyperion.[2] the ships with the armor that the god had given She has two siblings, a brother (Sol, the sun) and a sis- her. (19.1) ter (Luna, the moon). Rarely Roman writers[3] imitated Hesiod and later Greek poets and named Aurora as the mother of the Anemoi (the Winds), who were the off- But soon as early Dawn appeared, the rosy- spring of Astraeus, the father of the stars. fingered, then gathered the folk about the pyre of glorious Hector. (24.776) Aurora appears most often in sexual poetry with one of her mortal lovers. A myth taken from the Greek by Ro- man poets tells that one of her lovers was the prince of From Virgil's Aeneid: Troy, Tithonus. -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

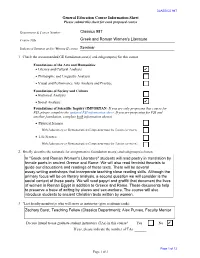

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please Submit This Sheet for Each Proposed Course

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Course Title Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities ñ Literary and Cultural Analysis ñ Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis ñ Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture ñ Historical Analysis ñ Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry (IMPORTAN: If you are only proposing this course for FSI, please complete the updated FSI information sheet. If you are proposing for FSI and another foundation, complete both information sheets) ñ Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) ñ Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs Page 1 of 12 Page 1 of 3 CLASSICS 98T 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2018-19 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2019-20 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2020-21 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units Is this an existing course that has been modified for inclusion in the new GE? Yes No If yes, provide a brief explanation of what has changed: Present Number of Units: Proposed Number of Units: 6. -

Fish Lists in the Wilderness

FISH LISTS IN THE WILDERNESS: The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree Author(s): Ephraim Lytle Source: Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April-June 2010), pp. 253-303 Published by: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40835487 . Accessed: 18/03/2014 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 71.168.218.10 on Tue, 18 Mar 2014 10:14:19 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions HESPERIA 79 (2OIO) FISH LISTS IN THE Pages 253~3°3 WILDERNESS The Social and Economic History of a Boiotian Price Decree ABSTRACT This articlepresents a newtext and detailedexamination of an inscribedHel- lenisticdecree from the Boiotian town of Akraiphia (SEG XXXII 450) that consistschiefly of lists of fresh- and saltwaterfish accompanied by prices. The textincorporates improved readings and restoresthe final eight lines of the document,omitted in previouseditions. -

Bibliography

Bibliography In this bibliography titles of journals are either written out or abbreviated according to the list provided by L’Année Philologique on-line (http://www.annee-philologique .com/files/sigles_fr.pdf). Abbreviations of specific editions are listed among the bio- graphical entries. Acheilara, L. 2004. ἐν τῶ ἴρω τῶ ἐμ Μέσσω. Mytilene. Acosta-Hughes, B. 2002. Polyeideia: The Iambi of Callimachus and the Archaic Iambic Tradition. Berkeley. 2010. Arion’s Lyre: Archaic Poetry into Hellenistic Poetry. Princeton. Adler = Adler, A. 1928–1938. Suidae Lexicon, i–v. Lipsiae. Agosti, G. 2001. Late Antique Iambics and Iambike Idea. In Cavarzere, Aloni, and Bar- chiesi (2001) 219–255. Akehurst, F.R. and J.M. Davis. 1995. A Handbook of the Troubadours. Berkeley. Albert, N. 2005. Saphisme et décadence dans l’art et la littérature en Europe à la fin du xixe siècle. Paris. Allan, W., ed. 2008. Euripides: Helen. Cambridge. Allen, T.W., W.R. Halliday, and E.E. Sikes, eds. 1936. The Homeric Hymns. Oxford. Aloni, A. 1983. Eteria e tiaso. I gruppi aristocratici di Lesbo tra economia e ideologia. Dialoghi di Archeologia Ser. 3, 1: 21–35. 1997. Saffo. Frammenti. Florence. 2001. What is That Man Doing in Sappho, fr. 31 v.? In Cavarzere, Aloni, and Barchiesi (2001) 29–40. Asheri, D., A. Lloyd, and A. Corcella. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus Books i–iv, eds. O. Murray and A. Moreno. Translated from the Italian by B. Graziosi et al. Oxford. Asper, M. 2004. Kallimachos. Werke. Darmstadt. Atallah, W. 1966. Adonis dans la littérature et l’art grecs. Paris. Austin, C.