A Study of the Rufous-Fronted Thornbird and Associated Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016 Jennifer Powell Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 2017 Photos: Nathan Marcy Common Chlorospingus Slate-throated Redstart (Chlorospingus flavopectus) (Myioborus miniatus) CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Project Background ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Project Goals ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Locations ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Current locations ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Historic locations ..........................................................................................................................................10 -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed Alphabetically by Last Name Of

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author AOS 2019 Meeting 24-28 June 2019 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Variability in the Use of Acoustic Space Between propensity, renesting intervals, and renest reproductive Two Tropical Forest Bird Communities success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) by fol- lowing 1,922 nests and 1,785 unique breeding adults Patrick J Hart, Kristina L Paxton, Grace Tredinnick from 2014 2016 in North and South Dakota, USA. The apparent renesting rate was 20%. Renesting propen- When acoustic signals sent from individuals overlap sity declined if reproductive attempts failed during the in frequency or time, acoustic interference and signal brood-rearing stage, nests were depredated, reproduc- masking occurs, which may reduce the receiver’s abil- tive failure occurred later in the breeding season, or ity to discriminate information from the signal. Under individuals had previously renested that year. Addi- the acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH), acoustic space is tionally, plovers were less likely to renest on reservoirs a resource that organisms may compete for, and sig- compared to other habitats. Renesting intervals de- naling behavior has evolved to minimize overlap with clined when individuals had not already renested, were heterospecific calling individuals. Because tropical after second-year adults without prior breeding experi- wet forests have such high bird species diversity and ence, and moved short distances between nest attempts. abundance, and thus high potential for competition for Renesting intervals also decreased if the attempt failed acoustic niche space, they are good places to examine later in the season. Lastly, overall reproductive success the way acoustic space is partitioned. -

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009

Check List 5(2): 222–237, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Birds (Aves), Serrania Sadiri, Parque Nacional Madidi, Depto. La Paz, Bolivia Peter Andrew Hosner 1 Kenneth David Behrens 2 A. Bennett Hennessey 3 1 University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Division of Ornithology. Dyche Hall, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66046. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tropical Birding, 1 Toucan Way. Bloubergrise 7441, South Africa. 3 Asociación Civil Armonía. Avenida Lomas de Arena, Casilla 3566, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Abstract We surveyed the Serrania Sadiri for birds at elevations between 500-950m for a combined total of 15 days in three different months. The area surveyed was along the Tumupasa/San Jose de Uchupiamones trail at the edge of Parque Nacional Madidi in Depto. La Paz, Bolivia. We report observations of 231 species of birds detected by sight and sound, including many outlying ridge specialists. We report and present photographs of a new species for Depto. La Paz (Caprimulgis nigrescens), the second Bolivian localities for Porphyrolaema prophyrolaema, Zimerius cinereicapillus, and Basileuterus chrysogaster, and five new species records for Parque Nacional Madidi. Introduction Foothills and outlying ridges of the Andes are From the small village of Tumupasa (14°8'46" S, often very difficult or impossible to access. As a 67°53'17" W; 400 m a.s.l; Figures 1 and 2), an old result, many of the specialist bird species in these trail leads generally southwest over the Serrania areas are poorly known and some only recently Sadiri to the town of San Jose de Uchupiamones described, and these areas generally have unique (14°12'47" S, 68°03'14" W; 520 m a.s.l). -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

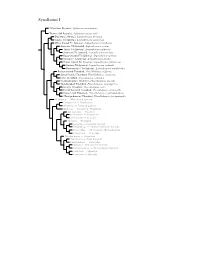

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied -

Northern Argentina Tour Report 2016

The enigmatic Diademed Sandpiper-Plover in a remote valley was the bird of the trip (Mark Pearman) NORTHERN ARGENTINA 21 OCTOBER – 12 NOVEMBER 2016 TOUR REPORT LEADER: MARK PEARMAN Northern Argentina 2016 was another hugely successful chapter in a long line of Birdquest tours to this region with some 524 species seen although, importantly, more speciality diamond birds were seen than on all previous tours. Highlights in the north-west included Huayco Tinamou, Puna Tinamou, Diademed Sandpiper-Plover, Black-and-chestnut Eagle, Red-faced Guan, Black-legged Seriema, Wedge-tailed Hilstar, Slender-tailed Woodstar, Black-banded Owl, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Black-bodied Woodpecker, White-throated Antpitta, Zimmer’s Tapaculo, Scribble-tailed Canastero, Rufous-throated Dipper, Red-backed Sierra Finch, Tucuman Mountain Finch, Short-tailed Finch, Rufous-bellied Mountain Tanager and a clean sweep on all the available endemcs. The north-east produced such highly sought-after species as Black-fronted Piping- Guan, Long-trained Nightjar, Vinaceous-breasted Amazon, Spotted Bamboowren, Canebrake Groundcreeper, Black-and-white Monjita, Strange-tailed Tyrant, Ochre-breasted Pipit, Chestnut, Rufous-rumped, Marsh and Ibera Seedeaters and Yellow Cardinal. We also saw twenty-fve species of mammal, among which Greater 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Northern Argentina 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com Naked-tailed Armadillo stole the top slot. As usual, our itinerary covered a journey of 6000 km during which we familiarised ourselves with each of the highly varied ecosystems from Yungas cloud forest, monte and badland cactus deserts, high puna and altiplano, dry and humid chaco, the Iberá marsh sytem (Argentina’s secret pantanal) and fnally a week of rainforest birding in Misiones culminating at the mind-blowing Iguazú falls. -

Association with Trypanosoma Cruzi, Different Habitats

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 48(5):532-538, Sep-Oct, 2015 Major Article http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0184-2015 Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) in the Pantanal region: association with Trypanosoma cruzi, diff erent habitats and vertebrate hosts Filipe Martins Santos[1], Ana Maria Jansen[2], Guilherme de Miranda Mourão[3], José Jurberg[4], Alessandro Pacheco Nunes[5] and Heitor Miraglia Herrera[1] [1]. Laboratório de Parasitologia Animal, Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. [2]. Laboratório de Biologia de Tripanossomatídeos, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [3]. Laboratório de Vida Selvagem, Centro de Pesquisa Agropecuária do Pantanal/Embrapa-Pantanal, Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. [4]. Laboratório Nacional e Internacional de Referência em Taxonomia de Triatomíneos, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [5]. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. ABSTRACT Introduction: The transmission cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi in the Brazilian Pantanal region has been studied during the last decade. Although considerable knowledge is available regarding the mammalian hosts infected by T. cruzi in this wetland, no studies have investigated its vectors in this region. This study aimed to investigate the presence of sylvatic triatomine species in different habitats of the Brazilian Pantanal region and to correlate their presence with the occurrences of vertebrate hosts and T. cruzi infection. Methods: The fi eldwork involved passive search by using light traps and Noireau traps and active search by visual inspection. -

A New Genus and Species of Furnariid (Aves: Furnariidae) from the Cocoa-Growing Region of Southeastern Bahia, Brazil

THEWILSONBULLETIN A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF ORNITHOLOGY Published by the Wilson Ornithological Society VOL. 108, No. 3 SEPTEMBER 1996 PAGES 397-606 Wilson Bull., 108(3), 1996, pp. 397-433 A NEW GENUS AND SPECIES OF FURNARIID (AVES: FURNARIIDAE) FROM THE COCOA-GROWING REGION OF SOUTHEASTERN BAHIA, BRAZIL Jose FERNANDO PACHECO,’ BRET M. WHITNEY,‘J AND LUIZ P. GONZAGA’ ABSTRACT.-we here describe Acrobatomis fonsecai, a new genus and species in the Furnariidae, from the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Bahia, Brazil. Among the outstanding features of this small, arboreal form are: black-and-gray definitive plumage lacking any rufous: juvenal plumage markedly different from adult; stout, bright-pink legs and feet; and its acrobatic foraging behavior involving almost constant inverted hangs on foliage and scansorial creeping along the undersides of canopy limbs. Analysis of morphology, vocal- izations, and behavior suggest to us a phylogenetic position close to Asfhenes and Crani- oleuca; in some respects, it appears close to the equally obscure Xenerpesres and Meto- pothrix. New data on the morphology, vocalizations, and behavior of several furuariids possibly related to Acrobatornis are presented in the context of intrafamilial relationships. We theorize that Acrobatornis could have colonized its current range during an ancient period of continental semiaridity that promoted the expansion of stick-nesting prototypes from a southern, Chaco-PatagonianE’antanal center, and today represents a relict that sur- vived by adapting to build its stick-nest in the relatively dry, open, canopy of leguminaceous trees of the contemporary humid forest in southeastern Bahia. Another theory of origin places emphasis on the fact that the closest relatives of practically all (if not all) other birds syntopic with Acrobatomis are of primarily Amazonian distribution.