On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSAP Madagascar Pond Heron

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 15 th MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Rome, Italy, 27-28 November 2008 UNEP/CMS/ScC15/Doc.6 DRAFT INTERNATIONAL SINGLE SPECIES ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OF THE MADAGASCAR POND HERON ARDEOLA IDAE (Introductory note prepared by the Secretariat) 1. The Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Madagascar Pond Heron Ardeola idae was initiated jointly by CMS and AEWA in 2007 upon a recommendation of the 14 th Meeting of the CMS Scientific Council. 2. The plan covers the entire range of this intra-African migrant. The drafting of the Plan was commissioned to the BirdLife International Africa Partnership Secretariat with financial support provided by the Ministry of Environment of Italy and was compiled by a team under the management of Paul Kariuki Ndang’ang’a. Earlier drafts of the Plan have been consulted extensively with experts and governmental officials at the Range States. 3. The Plan has already been adopted by the 4 th Meeting of the Parties to AEWA (Antananarivo, Madagascar, 15-19 September 2008). Action requested: The Scientific Council is requested to: a. review and endorse the Plan; and b. transmit the Plan to the Conference of the Parties for adoption. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/CMS concerning the legal status of any State, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers and boundaries. -

Territory Size and Stability in a Sedentary Neotropical Passerine: Is Resource Partitioning a Necessary Condition?

J. Field Ornithol. 76(4):395±401, 2005 Territory size and stability in a sedentary neotropical passerine: is resource partitioning a necessary condition? Janet V. Gorrell,1 Gary Ritchison,1,3 and Eugene S. Morton2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Kentucky 40475 USA 2 Hemlock Hill Field Station, 22318 Teepleville Flats Road, Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania 16403 USA Received 9 April 2004; accepted 11 April 2005 ABSTRACT. Long-term pair bonds and defense of territories year-round are common among tropical passer- ines. The boundaries of these territories tend to be stable, perhaps re¯ecting the need to defend an area that, regardless of conditions, provides suf®cient food resources. If, however, these stable territories are not, even tem- porarily, suf®ciently large, then intra-pair competition for available food may result, particularly in species with no sexual size dimorphism. With such competition, sex-speci®c differences in foraging behavior may result. Male and female Dusky Antbirds (Cercomacra tyrannina) are not size dimorphic, and pairs jointly defend territories throughout the year. Our objective was to determine if paired Dusky Antbirds exhibited sex-speci®c differences in foraging behavior. Foraging antbirds were observed in central Panama from February±July 2002 to determine if pairs par- titioned food resources. Males and females exhibited no differences in foraging behavior, with individuals of both sexes foraging at similar heights and using the same foraging maneuvers (glean, probe, and sally) and substrates (leaves, rolled leaves, and woody surfaces). These results suggest that Dusky Antbirds do not partition resources and that territory switching, rather than resource partitioning, may be the means by which they gain access to additional food resources. -

Antbird Guilds in the Lowland Caribbean Rainforest of Southeast Nicaragua1

The Condor 102:7X4-794 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 2000 ANTBIRD GUILDS IN THE LOWLAND CARIBBEAN RAINFOREST OF SOUTHEAST NICARAGUA1 MARTIN L. CODY Department of OrganismicBiology, Ecology and Evolution, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1606, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Some 20 speciesof antbirdsoccur in lowland Caribbeanrainforest in southeast Nicaragua where they form five distinct guilds on the basis of habitat preferences,foraging ecology, and foraging behavior. Three guilds are habitat-based,in Edge, Forest, and Gaps within forest; two are behaviorally distinct, with species of army ant followers and those foraging within mixed-species flocks. The guilds each contain 3-6 antbird species. Within guilds, species are segregatedby body size differences between member species, and in several guilds are evenly spaced on a logarithmic scale of body mass. Among guilds, the factors by which adjacent body sizes differ vary between 1.25 and 1.75. Body size differ- ences may be related to differences in preferred prey sizes, but are influenced also by the density of the vegetation in which each speciescustomarily forages. Resumen. Unas 20 especies de aves hormiguerasviven en el bosque tropical perenni- folio, surestede Nicaragua, donde se forman cinquo gremios distinctos estribando en pre- ferencias de habitat, ecologia y comportamiento de las costumbresde alimentacion. Las diferenciasentre las varias especiesson cuantificadaspor caractaristicasde1 ambiente vegetal y por la ecologia y comportamientode la alimentaci6n, y usadospara definir cinco grupos o gremios (“guilds”). Tres gremios se designanpor las relacionesde habitat: edge (margen), forest (selva), y gaps (aberturasadentro la selva); dos mas por comportamiento,partidarios de army ants (hormigasarmadas) y mixed-speciesflocks (forrejando en bandadasde especies mexcladas). -

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

MADAGASCAR: the Wonders of the “8Th Continent” a Tropical Birding Custom Trip

MADAGASCAR: The Wonders of the “8th Continent” A Tropical Birding Custom Trip October 20—November 6, 2016 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken during this trip by Ken Behrens Annotated bird list by Jerry Connolly TOUR SUMMARY Madagascar has long been a core destination for Tropical Birding, and with the opening of a satellite office in the country several years ago, we further solidified our expertise in the “Eighth Continent.” This custom trip followed an itinerary similar to that of our main set-departure tour. Although this trip had a definite bird bias, it was really a general natural history tour. We took our time in observing and photographing whatever we could find, from lemurs to chameleons to bizarre invertebrates. Madagascar is rich in wonderful birds, and we enjoyed these to the fullest. But its mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects are just as wondrous and accessible, and a trip that ignored them would be sorely missing out. We also took time to enjoy the cultural riches of Madagascar, the small villages full of smiling children, the zebu carts which seem straight out of the Middle Ages, and the ingeniously engineered rice paddies. If you want to come to Madagascar and see it all… come with Tropical Birding! Madagascar is well known to pose some logistical challenges, especially in the form of the national airline Air Madagascar, but we enjoyed perfectly smooth sailing on this tour. We stayed in the most comfortable hotels available at each stop on the itinerary, including some that have just recently opened, and savored some remarkably good food, which many people rank as the best Madagascar Custom Tour October 20-November 6, 2016 they have ever had on any birding tour. -

Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds

ES48CH11-Jonsson ARI 9 October 2017 7:38 Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds Knud Andreas Jønsson,1 Michael Krabbe Borregaard,1 Daniel Wisbech Carstensen,1 Louis A. Hansen,1 Jonathan D. Kennedy,1 Antonin Machac,1 Petter Zahl Marki,1,2 Jon Fjeldsa˚,1 and Carsten Rahbek1,3 1Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, 0318 Oslo, Norway 3Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot SL5 7PY, United Kingdom Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017. 48:231–53 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on Corvides, diversity assembly, evolution, island biogeography, Wallacea August 11, 2017 The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Abstract Systematics is online at ecolsys.annualreviews.org The archipelagos that form the transition between Asia and Australia were https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316- immortalized by Alfred Russel Wallace’s observations on the connections 022813 between geography and animal distributions, which he summarized in Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. what became the first major modern biogeographic synthesis. Wallace All rights reserved traveled the island region for eight years, during which he noted the marked Access provided by Copenhagen University on 11/19/17. For personal use only. faunal discontinuity across what has later become known as Wallace’s Line. Wallace was intrigued by the bewildering diversity and distribution of Annu. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

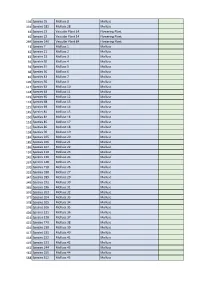

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Systematic Notes on Asian Birds. 28

ZV-340 179-190 | 28 04-01-2007 08:56 Pagina 179 Systematic notes on Asian birds. 28. Taxonomic comments on some south and south-east Asian members of the family Nectariniidae C.F. Mann Mann, C.F. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 28. Taxonomic comments on some south and south-east Asian members of the family Nectariniidae. Zool. Verh. Leiden 340, 27.xii.2002: 179-189.— ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-84-2. Clive F. Mann, 53 Sutton Lane South, London W4 3JR, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]). Keywords: Asia; Nectariniidae; taxonomy. Certain taxonomic changes made by Cheke & Mann (2001) are here explained and justified. Dicaeum haematostictum Sharpe, 1876, is split from D. australe (Hermann, 1783). D. aeruginosum Bourns & Worcester, 1894 is merged into D. agile (Tickell, 1833). The genus Chalcoparia Cabanis, 1851, is re-estab- lished for (Motacilla) singalensis Gmelin, 1788. The taxon Leptocoma sperata marinduquensis (duPont, 1971), is shown to be based on a specimen of Aethopyga siparaja magnifica Sharpe, 1876. Aethopyga vigor- sii (Sykes, 1832) is split from A. siparaja (Raffles, 1822). Cheke & Mann (op. cit.) mistakenly omitted two forms, Anthreptes malacensis erixanthus Oberholser, 1932 and Arachnothera longirostra zarhina Ober- holser, 1912. Five subspecies are removed from Aethopyga shelleyi Sharpe, 1876 to create the polytypic A. bella, Tweeddale, 1877. The Arachnothera affinis (Horsfield, 1822)/modesta (Eyton, 1839)/everetti (Sharpe, 1893) complex is re-evaluated in the light of the revision by Davison in Smythies (1999). Introduction In a recent publication (Cheke & Mann, 2001) some taxonomic changes were made to members of this family occurring in Asia. -

Sericornis, Acanthizidae)

GENETIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND PHYLOGENY IN THE AUSTRALO-PAPUAN SCRUBWRENS (SERICORNIS, ACANTHIZIDAE) LESLIE CHRISTIDIS,1'2 RICHARD $CHODDE,l AND PETER R. BAVERSTOCK 3 •Divisionof Wildlifeand Ecology, CSIRO, P.O. Box84, Lyneham,Australian Capital Territory 2605, Australia, 2Departmentof EvolutionaryBiology, Research School of BiologicalSciences, AustralianNational University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia, and 3EvolutionaryBiology Unit, SouthAustralian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia ASS•CRACr.--Theinterrelationships of 13 of the 14 speciescurrently recognized in the Australo-Papuan oscinine scrubwrens, Sericornis,were assessedby protein electrophoresis, screening44 presumptivelo.ci. Consensus among analysesindicated that Sericorniscomprises two primary lineagesof hithertounassociated species: S. beccarii with S.magnirostris, S.nouhuysi and the S. perspicillatusgroup; and S. papuensisand S. keriwith S. spiloderaand the S. frontalis group. Both lineages are shared by Australia and New Guinea. Patternsof latitudinal and altitudinal allopatry and sequencesof introgressiveintergradation are concordantwith these groupings,but many featuresof external morphologyare not. Apparent homologiesin face, wing and tail markings, used formerly as the principal criteria for grouping species,are particularly at variance and are interpreted either as coinherited ancestraltraits or homo- plasies. Distribution patternssuggest that both primary lineageswere first split vicariantly between -

12(3) Island Representative Reports—St

ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE REPORTS— DOMINICA lands are expected to be included as part of the Wren Troglodytes aedon, Broad Wing Hawk Buteo Morne Diablotin National Park. platypterus, and Bananaquit Coereba flaveola). BIRD NEST MONITORING OTHER ACTITIES Bird nest monitoring was conducted by Benito • Overseas visit – November 1998, Trinidad – Espinal and Bertrand Jno Baptiste, who expect to FAO Workshop on Management of wild bird publish their data later this year. This research activ- population in the West Indies. ity has resulted in an exciting discovery for Domin- • ica; i.e., it has been confirmed that the Bare-eyed Training for Tour Guides in Fauna and Flora of Thrush (Turdus nidigenis) is a resident breeder in an Dominica. area known as Pentiwax. This study also confirmed • Participation in International Migratory Bird that both the Bare-eyed Thrush and the Red-legged Day and World Birdwatch Day. Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) are using soil in the con- • Search for Bare-eyed Thrush in several habitats struction of their nest. Several other bird nests were around the island. observed (including Barn Owl Tyto alba, House ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE REPORT ST. LUCIA DONALD ANTHONY ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE—ST. LUCIA Forestry Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Castries, St. Lucia This report is a summary of the main activities Three tree top observation platforms were replaced in within the Wildlife Section of the Forestry Depart- Quilesse. They had been in place since September ment in St. Lucia from August 1998 to July 1999. 1994, but succumbed to the elements in the forest ca- nopy. PARROT PROJECT For the first time ever the fully decomposed re- mains of an adult parrot were found in the wild. -

Predation on Vertebrates by Neotropical Passerine Birds Leonardo E

Lundiana 6(1):57-66, 2005 © 2005 Instituto de Ciências Biológicas - UFMG ISSN 1676-6180 Predation on vertebrates by Neotropical passerine birds Leonardo E. Lopes1,2, Alexandre M. Fernandes1,3 & Miguel Â. Marini1,4 1 Depto. de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, 31270-910, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Current address: Coleções Zoológicas, Aves, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Avenida André Araújo, 2936, INPA II, 69083-000, Manaus, AM, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 4 Current address: Lab. de Ornitologia, Depto. de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de Brasília, 70910-900, Brasília, DF, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We investigated if passerine birds act as important predators of small vertebrates within the Neotropics. We surveyed published studies on bird diets, and information on labels of museum specimens, compiling data on the contents of 5,221 stomachs. Eighteen samples (0.3%) presented evidence of predation on vertebrates. Our bibliographic survey also provided records of 203 passerine species preying upon vertebrates, mainly frogs and lizards. Our data suggest that vertebrate predation by passerines is relatively uncommon in the Neotropics and not characteristic of any family. On the other hand, although rare, the ability to prey on vertebrates seems to be widely distributed among Neotropical passerines, which may respond opportunistically to the stimulus of a potential food item. -

Passive Citizen Science: the Role of Social Media in Wildlife Observations

Passive citizen science: the role of social media in wildlife observations 1Y* 1Y 1Y Thomas Edwards , Christopher B. Jones , Sarah E. Perkins2, Padraig Corcoran 1 School Of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK 2 School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF10 3AX YThese authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract Citizen science plays an important role in observing the natural environment. While conventional citizen science consists of organized campaigns to observe a particular phenomenon or species there are also many ad hoc observations of the environment in social media. These data constitute a valuable resource for `passive citizen science' - the use of social media that are unconnected to any particular citizen science program, but represent an untapped dataset of ecological value. We explore the value of passive citizen science, by evaluating species distributions using the photo sharing site Flickr. The data are evaluated relative to those submitted to the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Atlas, the largest collection of species distribution data in the UK. Our study focuses on the 1500 best represented species on NBN, and common invasive species within UK, and compares the spatial and temporal distribution with NBN data. We also introduce an innovative image verification technique that uses the Google Cloud Vision API in combination with species taxonomic data to determine the likelihood that a mention of a species on Flickr represents a given species. The spatial and temporal analyses for our case studies suggest that the Flickr dataset best reflects the NBN dataset when considering a purely spatial distribution with no time constraints.