Passive Citizen Science: the Role of Social Media in Wildlife Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Skipper Butterfly (Thymelicus Lineola) Associated

European Skipper Butterfly ( Thymelicus lineola ) Associated with Reduced Seed Development of Showy Lady’s-slipper Orchid (Cypripedium reginae ) PETER W. H ALL 1, 5, P AUL M. C ATLING 2, P AUL L. M OSQUIN 3, and TED MOSQUIN 4 124 Wendover Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 4Z7 Canada 2170 Sanford Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K2C 0E9 Canada 3Research Triangle International, 3040 East Cornwallis Road, P.O. Box 12194, Raleigh, North Carolina 27709-2194 USA 43944 McDonalds Corners Road, Balderson, Ontario K0G 1A0 Canada 5Corresponding author: [email protected] Hall, Peter W., Paul M. Catling, Paul L. Mosquin, and Ted Mosquin. 2017. European Skipper butterfly ( Thymelicus lineola ) associated with reduced seed development of Showy Lady’s-slipper orchid ( Cypripedium reginae ). Canadian Field- Naturalist 131(1): 63 –68. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v 131i 1. 1952 It has been suggested that European Skipper butterflies ( Thymelicus lineola ) trapped in the lips of the Showy Lady’s-slipper orchid ( Cypripedium reginae ) may interfere with pollination. This could occur through blockage of the pollinator pathway, facilitation of pollinator escape without pollination, and/or disturbance of the normal pollinators. A large population of the orchid at an Ottawa Valley site provided an opportunity to test the interference hypothesis. The number of trapped skippers was compared in 475 post-blooming flowers with regard to capsule development and thus seed development. The presence of any skippers within flowers was associated with reduced capsule development ( P = 0.0075), and the probability of capsule development was found to decrease with increasing numbers of skippers ( P = 0.0271). The extent of a negative effect will depend on the abundance of the butterflies and the coincidence of flowering time and other factors. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

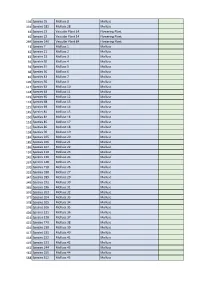

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Endangered Species (Protection, Conser Va Tion and Regulation of Trade)

ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSER VA TION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) THE ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Preliminary Short title. Interpretation. Objects of Act. Saving of other laws. Exemptions, etc., relating to trade. Amendment of Schedules. Approved management programmes. Approval of scientific institution. Inter-scientific institution transfer. Breeding in captivity. Artificial propagation. Export of personal or household effects. PART I. Administration Designahem of Mana~mentand establishment of Scientific Authority. Policy directions. Functions of Management Authority. Functions of Scientific Authority. Scientific reports. PART II. Restriction on wade in endangered species 18. Restriction on trade in endangered species. 2 ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULA TION OF TRADE) Regulation of trade in species spec fled in the First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedules Application to trade in endangered specimen of species specified in First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Importation of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Introduction from the sea certificate for specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Introduction from the sea of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Export of specimens specified in Fourth Schedule. PART 111. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update

Secretariat provided by the Workshop 3 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Doc TC 8.25 21 February 2008 8th MEETING OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE 03 - 05 March 2008, Bonn, Germany ___________________________________________________________________________ Review of the Status of Introduced Non-Native Waterbird Species in the Area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 Update Authors A.N. Banks, L.J. Wright, I.M.D. Maclean, C. Hann & M.M. Rehfisch February 2008 Report of work carried out by the British Trust for Ornithology under contract to AEWA Secretariat © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................5 List of Figures.........................................................................................................................................7 List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................................9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................11 RECOMMENDATIONS .....................................................................................................................13 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................15 -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

SICHUAN (Including Northern Yunnan)

Temminck’s Tragopan (all photos by Dave Farrow unless indicated otherwise) SICHUAN (Including Northern Yunnan) 16/19 MAY – 7 JUNE 2018 LEADER: DAVE FARROW The Birdquest tour to Sichuan this year was a great success, with a slightly altered itinerary to usual due to the closure of Jiuzhaigou, and we enjoyed a very smooth and enjoyable trip around the spectacular and endemic-rich mountain and plateau landscapes of this striking province. Gamebirds featured strongly with 14 species seen, the highlights of them including a male Temminck’s Tragopan grazing in the gloom, Chinese Monal trotting across high pastures, White Eared and Blue Eared Pheasants, Lady Amherst’s and Golden Pheasants, Chinese Grouse and Tibetan Partridge. Next were the Parrotbills, with Three-toed, Great and Golden, Grey-hooded and Fulvous charming us, Laughingthrushes included Red-winged, Buffy, Barred, Snowy-cheeked and Plain, we saw more Leaf Warblers than we knew what to do with, and marvelled at the gorgeous colours of Sharpe’s, Pink-rumped, Vinaceous, Three-banded and Red-fronted Rosefinches, the exciting Przevalski’s Finch, the red pulse of Firethroats plus the unreal blue of Grandala. Our bird of the trip? Well, there was that Red Panda that we watched for ages! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Sichuan Including Northern Yunnan 2018 www.birdquest-tours.com Our tour began with a short extension in Yunnan, based in Lijiang city, with the purpose of finding some of the local specialities including the rare White-speckled Laughingthrush, which survives here in small numbers. Once our small group had arrived in the bustling city of Lijiang we began our birding in an area of hills that had clearly been totally cleared of forest in the fairly recent past, with a few trees standing above the hillsides of scrub. -

Ecography E4831 Yamaura, Y., Katoh, K

Ecography E4831 Yamaura, Y., Katoh, K. and Takahashi, T. 2006. Reversing habitat loss: deciduous habitat fragmentation matters to birds in a larch plantation matrix. – Ecography 29: 827–834. Appendix. Assignment of bird species to groups. Common name Scientific name Season Winter guild Breeding guild Nest location Black-faced bunting Emberiza spodocephala Breeding Ground, Ground, early successional shrub Blue-and-white flycatcher Cyanoptila cyanomelana Breeding Flycatcher Ground Brambling Fringilla montifringilla Winter Seed Shrub Brown thrush Turdus chrysolaus Breeding Ground Shrub Brown-eared bulbul Hypsipetes amaurotis Breeding Omnivore Shrub Bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula Both Seed Canopy, Shrub hemlock-fir Bush warbler Cettia diphone Breeding Shrub Shrub Coal tit Parus ater Both Canopy, Canopy, Tree hemlock-fir hemlock-fir Copper pheasant Phasianus soemmerringii Breeding Ground Ground Eastern crowned warbler Pylloscopus coronatus Breeding Shrub Ground Goldcrest Regulus regulus Winter Canopy, Tree hemlock-fir Great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major Winter Stem Tree Great tit Parus major Both Canopy Canopy Tree Indian tree pipit Anthus hodgsoni Breeding Ground, Ground early successional Japanese grey thrush Turdus cardis Breeding Ground Shrub Japanese grosbeak Eophona personata Both Seed Canopy Tree Japanese pygmy woodpecker Dendrocopos kizuki Both Stem Stem Tree Japanese white-eye Zosterops japonica Both Canopy Canopy Shrub Jay Garrulus glandarius Both Seed Omnivore Tree “Large woodpeckers” Breeding Stem Tree Long-tailed tit Aegithalos -

The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011

EEA Technical report No 11/2013 The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011 ISSN 1725-2237 EEA Technical report No 11/2013 The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011 Cover design: EEA Cover photo © Chris van Swaay, Orangetip (Anthocharis cardamines) Layout: EEA/Pia Schmidt Copyright notice © European Environment Agency, 2013 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Information about the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 ISBN 978-92-9213-402-0 ISSN 1725-2237 doi:10.2800/89760 REG.NO. DK-000244 European Environment Agency Kongens Nytorv 6 1050 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel.: +45 33 36 71 00 Fax: +45 33 36 71 99 Web: eea.europa.eu Enquiries: eea.europa.eu/enquiries Contents Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Summary .................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 9 2 Building the European Grassland Butterfly Indicator ........................................... 12 Fieldwork .............................................................................................................. 12 Grassland butterflies ............................................................................................. -

Alopochen Aegyptiaca) Para La Jurisdicción De La Corporación Autónoma Regional De Cundinamarca CAR

Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca CAR 9 1 Biodiversidad 20 Biodiversidad - DRN - Fuente: CAR CAR Fuente: 2019 Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca-CAR Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca CAR 2 DIRECCIÓN DE RECURSOS NATURALES DRN NÉSTOR GUILLERMO FRANCO GONZÁLES Director General CESAR CLAVIJO RÍOS Director Técnico DRN JOHN EDUARD ROJAS ROJAS Coordinador Grupo de Biodiversidad DRN DIANA PAOLA ROMERO CUELLAR Zoot-Esp. Grupo de Biodiversidad DRN CORPORACIÓN AUTÓNOMA REGIONAL DE CUNDINAMARCA CAR 2019 Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca-CAR 3 Los textos de este documento podrán ser utilizados total o parcialmente siempre y cuando sea citada la fuente. Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca Bogotá-Colombia Diciembre 2019 Este documento deberá citarse como: Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca CAR. 2019. Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca CAR. 30p. 2019. Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca CAR. Todos los derechos reservados Plan de Prevención, Control y Manejo del Ganso del Nilo (Alopochen aegyptiaca) para la jurisdicción de la Corporación Autónoma Regional de Cundinamarca-CAR Contenido 1. -

Wild China – Sichuan's Birds & Mammals

Wild China – Sichuan’s Birds & Mammals Naturetrek Tour Report 9 - 24 November 2019 Golden snub-nosed Monkey White-browed Rosefinch Himalayan Vulture Red Panda Report and images compiled by Barrie Cooper Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Wild China – Sichuan’s Birds & Mammals Tour participants: Barrie Cooper (leader), Sid Francis (Local Guide), with six Naturetrek clients. Summary Sichuan is a marvellous part of China with spectacular scenery, fine food and wonderful wildlife. We had a rich variety of mammals and birds on this trip. Mammals included Red Panda, Golden Snub-nosed Monkey, the endemic Chinese Desert Cat, Pallas’s Cat on two days, including during the daytime. The “golden fleece animal” –Takin never fails to attract the regular attention of cameras. A good range of bird species, including several endemics, was also recorded and one lucky group member now has Temminck’s Tragopan on his list. Day 1 Saturday 9th November The Cathay Pacific flight from Heathrow to Hong Kong had its usual good selection of films and decent food. Day 2 Sunday 10th November The group of three from London, became seven when we met the others at the gate for the connecting flight to Chengdu the following morning. Unfortunately, the flight was delayed by an hour but we had the compensation of warm, sunny weather at Chengdu where we met up with our local guide Sid. After a couple of hours of driving, we arrived at our hotel in Dujiangyan.