The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator: 1990–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

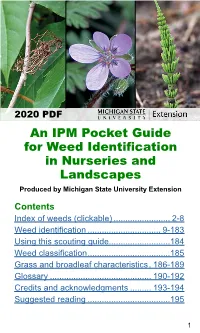

An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension

Back to table of contents Back to index 2020 PDF An IPM Pocket Guide for Weed Identification in Nurseries and Landscapes Produced by Michigan State University Extension Contents Index of weeds (clickable) ........................ 2-8 Weed identification ............................... 9-183 Using this scouting guide..........................184 Weed classification ...................................185 Grass and broadleaf characteristics . 186-189 Glossary ........................................... 190-192 Credits and acknowledgments ......... 193-194 Suggested reading ...................................195 1 Back to table of contents Back to index Index By common name Annual bluegrass ...........................................32-33 Annual sowthistle................................................73 Asiatic (common) dayflower ..........................18-19 Barnyardgrass ....................................................27 Bindweed, field ..........................................101-103 Bindweed, hedge .......................................102-103 Birdseye pearlwort ..............................................98 Birdsfoot trefoil...........................................109-110 Bittercress, hairy ............................................83-85 Bittercress, smallflowered...................................85 Black medic ............................................... 112-113 Blackseed plantain ...........................................150 Bluegrass, annual ..........................................32-33 Brambles ...................................................164-165 -

Pollinator–Friendly Parks

POLLINATOR–FRIENDLY PARKS How to Enhance Parks, Gardens, and Other Greenspaces for Native Pollinator Insects Matthew Shepherd, Mace Vaughan, and Scott Hoffman Black The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, Portland, OR The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation is an international, nonprofit, member–supported organiza- tion dedicated to preserving wildlife and its habitat through the conservation of invertebrates. The Society promotes protection of invertebrates and their habitat through science–based advocacy, conservation, and education projects. Its work focuses on three principal areas—endangered species, watershed health, and pollinator conservation. Copyright © 2008 (2nd Edition) The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. 4828 SE Hawthorne Boulevard, Portland, OR 97215 Tel (503) 232-6639 Fax (503) 233-6794 www.xerces.org Acknowledgements Thank you to Bruce Barbarasch (Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District, OR) and Lisa Hamerlynck (City of Lake Oswego, OR) for reviewing early drafts. Their guidance and suggestions greatly improved these guide- lines. Thank you to Eric Mader and Jessa Guisse for help with the plant lists, and to Caitlyn Howell and Logan Lauvray for editing assistance. Funding for our pollinator conservation program has been provided by the Bradshaw-Knight Foundation, the Bullitt Foundation, the Columbia Foundation, the CS Fund, the Disney Wildlife Conservation Fund, the Dudley Foundation, the Gaia Fund, NRCS Agricultural Wildlife Conservation Center, NRCS California, NRCS West National Technical Support Center, the Panta Rhea Foundation, the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Founda- tion, the Turner Foundation, the Wildwood Foundation, and Xerces Society members Photographs We are grateful to Jeff Adams, Scott Bauer/USDA–ARS, John Davis/GORGEous Nature, Chris Evans/ www.forestryimages.com, Bruce Newhouse, Jeff Owens/Metalmark Images, and Edward S. -

NEWSLETTER Issue 4

NEWSLETTER Issue 4 October 2008 CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Introduction 1&2 Contact Details / Dates for your Diary / EIG Website 3 A Code of Practice for Butterfly Recording and Photography in Europe 4&5 A List of European Butterflies – A Role for EIG 6,7&8 Mount Chelmos, Greece 2008 Visit 9&10 Discovering Butterflies in Turkey’s Kaçkar Mountains 11&12 EIG Surveys in Hungary May – June 2008 13,14&15 Efforts for the Conservation of the Scarce Heath in Bavaria 16,17&18 Jardins de Proserpine 19 Spring into the Algarve 20&21 INTRODUCTION EIG now has 147 members and has had a successful year. In this Newsletter there are two reports of successful trips by EIG members to Mount Chelmos in Greece (Page 9 & 10) and to Hungary (Page 11,12 & 13). These activities are beginning to influence local National Parks and it was encouraging to hear that grazing has resumed in the Latrany Valley in Hungary something that the West Midlands group that went to Hungary in 2006 recommended. It was this group that formed EIG. We are able to organize activities in Europe only if we don’t fall foul of the 1991 EU Travel Directive and the 1993 EU Package Travel Directive. This means for all EIG trips we have to either use a travel company such as Ecotours or book our own flights and accommodation as we did in Greece or to travel independently and meet up at the arranged site as we did in the Ecrins last year. There is however an insurance issue outstanding, which would cover BC from, claims from anyone participating in the same way as they are covered by BC’s insurance for a field event or work party in the UK. -

A Note on the Recent Distribution of Aporia Crataegi (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Czech Republic (Lepidoptera, Pieridae) 453-454 ©Ges

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Atalanta Jahr/Year: 2000 Band/Volume: 31 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fric Zdenek Flatynek, Hula Vladimir, Konvicka Martin, Pavlicko Alois Artikel/Article: A note on the recent distribution of Aporia crataegi (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Czech Republic (Lepidoptera, Pieridae) 453-454 ©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (December 2000) 31 (3/4):453-454, Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 A note on the recent distribution of Aporia crataegi (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Czech Republic (Lepidoptera, Pieridae) by Z d e n e k Fr ic, V l a d im ír H u la , M a r t in K o n v ic k a & A lo is Pa v l ic k o received 20.X.2000 Eitschberger & Steiniger (2000), in their overview of records of Aporia crataegi in Germany, mentioned an interesting occurrence of this species in Wellertal, Silberbach and between Hohenberg, Fichtelgebirge and Dubina, closely to the German-Czech Republic border. The au thors speculated that the individuals originated from Czech territory. To understand the con text of their records, it is necessary to take into account the recent distribution of this species in the Czech Republic. Approximately since the 1950s, this butterfly species had been declining and gradually disap peared from both Bohemia and Moravia (Novak & Liska, 1997; Lastuvka, 1998; Beun, 1999), although there were occasional invasions followed by establishments of transient populations, such as near Pribram in the 1970s (Zeleny, 1977). -

List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017

Washington Natural Heritage Program List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017 The following list of animals known from Washington is complete for resident and transient vertebrates and several groups of invertebrates, including odonates, branchipods, tiger beetles, butterflies, gastropods, freshwater bivalves and bumble bees. Some species from other groups are included, especially where there are conservation concerns. Among these are the Palouse giant earthworm, a few moths and some of our mayflies and grasshoppers. Currently 857 vertebrate and 1,100 invertebrate taxa are included. Conservation status, in the form of range-wide, national and state ranks are assigned to each taxon. Information on species range and distribution, number of individuals, population trends and threats is collected into a ranking form, analyzed, and used to assign ranks. Ranks are updated periodically, as new information is collected. We welcome new information for any species on our list. Common Name Scientific Name Class Global Rank State Rank State Status Federal Status Northwestern Salamander Ambystoma gracile Amphibia G5 S5 Long-toed Salamander Ambystoma macrodactylum Amphibia G5 S5 Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Amphibia G5 S3 Ensatina Ensatina eschscholtzii Amphibia G5 S5 Dunn's Salamander Plethodon dunni Amphibia G4 S3 C Larch Mountain Salamander Plethodon larselli Amphibia G3 S3 S Van Dyke's Salamander Plethodon vandykei Amphibia G3 S3 C Western Red-backed Salamander Plethodon vehiculum Amphibia G5 S5 Rough-skinned Newt Taricha granulosa -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

Dragonflies and Damselflies in Your Garden

Natural England works for people, places and nature to conserve and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and wildlife in rural, urban, coastal and marine areas. Dragonflies and www.naturalengland.org.uk © Natural England 2007 damselflies in your garden ISBN 978-1-84754-015-7 Catalogue code NE21 Written by Caroline Daguet Designed by RR Donnelley Front cover photograph: A male southern hawker dragonfly. This species is the one most commonly seen in gardens. Steve Cham. www.naturalengland.org.uk Dragonflies and damselflies in your garden Dragonflies and damselflies are Modern dragonflies are tiny by amazing insects. They have a long comparison, but are still large and history and modern species are almost spectacular enough to capture the identical to ancestors that flew over attention of anyone walking along a prehistoric forests some 300 million river bank or enjoying a sunny years ago. Some of these ancient afternoon by the garden pond. dragonflies were giants, with This booklet will tell you about the wingspans of up to 70 cm. biology and life-cycles of dragonflies and damselflies, help you to identify some common species, and tell you how you can encourage these insects to visit your garden. Male common blue damselfly. Most damselflies hold their wings against their bodies when at rest. BDS Dragonflies and damselflies belong to Dragonflies the insect order known as Odonata, Dragonflies are usually larger than meaning ‘toothed jaws’. They are often damselflies. They are stronger fliers and referred to collectively as ‘dragonflies’, can often be found well away from but dragonflies and damselflies are two water. When at rest, they hold their distinct groups. -

Integrative Analyses Unveil Speciation Linked to Host Plant Shift in Spialia Butterflies

Molecular Ecology (2016) doi: 10.1111/mec.13756 Integrative analyses unveil speciation linked to host plant shift in Spialia butterflies JUAN L. HERNANDEZ-ROLDAN,*† 1 LEONARDO DAPPORTO,*‡ 1 VLAD DINCA,*§ JUAN C. VICENTE,¶ EMILY A. HORNETT,** JINDRA SICHOVA,†† VLADIMIR A. LUKHTANOV,‡‡§§ GERARD TALAVERA*¶¶ and ROGER VILA* *Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Passeig Marıtim de la Barceloneta 37, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain, †Departamento de Biologıa (Zoologıa), Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, C/ Darwin 2, E-28049 Madrid, Spain, ‡Department of Biology, University of Florence, Via Madonna del Piano 6, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino, FI, Italy, §Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1, ¶C/ Witerico, 9A – Bajo B, E-28025 Madrid, Spain, **Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK, ††Institute of Entomology, Biology Centre ASCR, 370 05 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic, ‡‡Department of Karyosystematics, Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia, §§Department of Entomology, St. Petersburg State University, Universitetskaya nab. 7/9, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia, ¶¶Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Abstract Discovering cryptic species in well-studied areas and taxonomic groups can have pro- found implications in understanding eco-evolutionary processes and in nature conser- vation because such groups often involve research models and act as flagship taxa for nature management. In this study, we use an array of techniques to study the butter- flies in the Spialia sertorius species group (Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae). The integration of genetic, chemical, cytogenetic, morphological, ecological and microbiological data indicates that the sertorius species complex includes at least five species that differen- tiated during the last three million years. -

Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecological Specialization of Baculoviruses: A

Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecological Specialization of Baculoviruses: A Treasure Trove for Future Applied Research Julien Thézé, Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde, Jenny Cory, Elisabeth Herniou To cite this version: Julien Thézé, Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde, Jenny Cory, Elisabeth Herniou. Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecological Specialization of Baculoviruses: A Treasure Trove for Future Applied Research. Viruses, MDPI, 2018, 10 (7), pp.366. 10.3390/v10070366. hal-02140538 HAL Id: hal-02140538 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02140538 Submitted on 26 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License viruses Article Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecological Specialization of Baculoviruses: A Treasure Trove for Future Applied Research Julien Thézé 1,2, Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde 1,3 ID , Jenny S. Cory 4 and Elisabeth A. Herniou 1,* ID 1 Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l’Insecte, UMR 7261, CNRS—Université de Tours, 37200 Tours, France; [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] -

2017, Jones Road, Near Blackhawk, RAIN (Photo: Michael Dawber)

Edited and Compiled by Rick Cavasin and Jessica E. Linton Toronto Entomologists’ Association Occasional Publication # 48-2018 European Skippers mudpuddling, July 6, 2017, Jones Road, near Blackhawk, RAIN (Photo: Michael Dawber) Dusted Skipper, April 20, 2017, Ipperwash Beach, LAMB American Snout, August 6, 2017, (Photo: Bob Yukich) Dunes Beach, PRIN (Photo: David Kaposi) ISBN: 978-0-921631-53-7 Ontario Lepidoptera 2017 Edited and Compiled by Rick Cavasin and Jessica E. Linton April 2018 Published by the Toronto Entomologists’ Association Toronto, Ontario Production by Jessica Linton TORONTO ENTOMOLOGISTS’ ASSOCIATION Board of Directors: (TEA) Antonia Guidotti: R.O.M. Representative Programs Coordinator The TEA is a non-profit educational and scientific Carolyn King: O.N. Representative organization formed to promote interest in insects, to Publicity Coordinator encourage cooperation among amateur and professional Steve LaForest: Field Trips Coordinator entomologists, to educate and inform non-entomologists about insects, entomology and related fields, to aid in the ONTARIO LEPIDOPTERA preservation of insects and their habitats and to issue Published annually by the Toronto Entomologists’ publications in support of these objectives. Association. The TEA is a registered charity (#1069095-21); all Ontario Lepidoptera 2017 donations are tax creditable. Publication date: April 2018 ISBN: 978-0-921631-53-7 Membership Information: Copyright © TEA for Authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Annual dues: reproduced or used without written permission. Individual-$30 Student-free (Association finances permitting – Information on submitting records, notes and articles to beyond that, a charge of $20 will apply) Ontario Lepidoptera can be obtained by contacting: Family-$35 Jessica E. -

Integrative Analyses Unveil Speciation Linked to Host Plant Shift in Spialia

1 Integrative analyses unveil speciation linked to host plant shift in 2 Spialia butterflies 3 4 5 JUAN L. HERNÁNDEZ-ROLDÁN1,2*, LEONARDO DAPPORTO1,3*, VLAD DINCĂ 1,4, JUAN C. 6 VICENTE5, EMILY A. HORNETT6, JINDRA ŠÍCHOVÁ7, VLADIMIR LUKHTANOV8,9, GERARD 7 TALAVERA1,10 & ROGER VILA1 8 9 1Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 10 37, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain 11 2Departamento de Biología (Zoología), Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 12 C/ Darwin, 2, E-28049 Madrid, Spain 13 3Department of Biology, University of Florence, Via Madonna del Piano 6, 50019, Sesto Fiorentino 14 (FI), Italy 15 4Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, N1G 2W1, Canada 16 5C/ Witerico, 9A - Bajo B, E-28025 Madrid, Spain 17 6Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, UK 18 7Institute of Entomology, Biology Centre ASCR, České Budějovice, Czech Republic 19 8Department of Karyosystematics, Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, St. 20 Petersburg, Russia 21 9Department of Entomology, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia 22 10Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Comparative Zoology, 23 Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 24 25 * These authors contributed equally to this work 26 27 Key words: Biogeography, butterflies, Lepidoptera, new species, phylogeny, speciation 28 29 Correspondence: Roger Vila, Fax: +34 932211011; E-mail: [email protected] 30 31 Running title: Speciation linked to host plant shift in Spialia 32 33 Abstract 34 Discovering cryptic species in well-studied areas and taxonomic groups can have profound implications in 35 understanding eco-evolutionary processes and in nature conservation because such groups often involve research 36 models and act as flagship taxa for nature management.