The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature Must Be Drastically Improved Before It Is Too Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

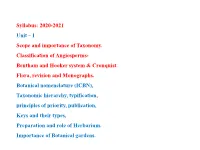

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 ISBN 0 85301 006 4 The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. Ride, Chairman H.G. Cogger C. Dupuis O. Kraus A. Minelli F. C. Thompson P.K. Tubbs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Explanatory Note This Code has been adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and has been ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) acting on behalf of the Union's General Assembly. The Commission may authorize official texts in any language, and all such texts are equivalent in force and meaning (Article 87). The Code proper comprises the Preamble, 90 Articles (grouped in 18 Chapters) and the Glossary. Each Article consists of one or more mandatory provisions, which are sometimes accompanied by Recommendations and/or illustrative Examples. In interpreting the Code the meaning of a word or expression is to be taken as that given in the Glossary (see Article 89). -

Comparative Functional Morphology of Attachment Devices in Arachnida

Comparative functional morphology of attachment devices in Arachnida Vergleichende Funktionsmorphologie der Haftstrukturen bei Spinnentieren (Arthropoda: Arachnida) DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Jonas Otto Wolff geboren am 20. September 1986 in Bergen auf Rügen Kiel, den 2. Juni 2015 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Stanislav N. Gorb _ Zweiter Gutachter: Dr. Dirk Brandis _ Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Juli 2015 _ Zum Druck genehmigt: 17. Juli 2015 _ gez. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang J. Duschl, Dekan Acknowledgements I owe Prof. Stanislav Gorb a great debt of gratitude. He taught me all skills to get a researcher and gave me all freedom to follow my ideas. I am very thankful for the opportunity to work in an active, fruitful and friendly research environment, with an interdisciplinary team and excellent laboratory equipment. I like to express my gratitude to Esther Appel, Joachim Oesert and Dr. Jan Michels for their kind and enthusiastic support on microscopy techniques. I thank Dr. Thomas Kleinteich and Dr. Jana Willkommen for their guidance on the µCt. For the fruitful discussions and numerous information on physical questions I like to thank Dr. Lars Heepe. I thank Dr. Clemens Schaber for his collaboration and great ideas on how to measure the adhesive forces of the tiny glue droplets of harvestmen. I thank Angela Veenendaal and Bettina Sattler for their kind help on administration issues. Especially I thank my students Ingo Grawe, Fabienne Frost, Marina Wirth and André Karstedt for their commitment and input of ideas. -

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Fall Webworm, Hyphantria

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 6 172 International Journal of Biological Sciences 2010; 6(2):172-186 © Ivyspring International Publisher. All rights reserved Research Paper The complete mitochondrial genome of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) Fang Liao1,2, Lin Wang3, Song Wu4, Yu-Ping Li4, Lei Zhao1, Guo-Ming Huang2, Chun-Jing Niu2, Yan-Qun Liu4, , Ming-Gang Li1, 1. College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin 300071, China 2. Tianjin Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Tianjin 300457, China 3. Beijing Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Beijing 101113, China 4. College of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Shenyang Agricultural University, Liaoning, Shenyang 110866, China Corresponding author: Y. Q. Liu, College of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Shenyang Agricultural University, Liaoning, Shenyang 110866, China; Tel: 86-24-88487163; E-mail: [email protected]. Or to: M. G. Li, College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin 300071, China; Tel: 86-22-23508237; E-mail: [email protected]. Received: 2010.02.03; Accepted: 2010.03.26; Published: 2010.03.29 Abstract The complete mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) was determined. The genome is a circular molecule 15 481 bp long. It presents a typical gene organization and order for completely sequenced lepidopteran mitogenomes, but differs from the insect ancestral type for the placement of tRNAMet. The nucleotide composition of the genome is also highly A + T biased, accounting for 80.38%, with a slightly positive AT skewness (0.010), indicating the occurrence of more As than Ts, as found in the Noctuoidea species. All protein-coding genes (PCGs) are initiated by ATN codons, except for COI, which is tentatively designated by the CGA codon as observed in other le- pidopterans. -

First Report of Ancylostoma Ceylanicum in Wild Canids Q ⇑ Felicity A

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 2 (2013) 173–177 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Brief Report First report of Ancylostoma ceylanicum in wild canids q ⇑ Felicity A. Smout a, R.C. Andrew Thompson b, Lee F. Skerratt a, a School of Public Health, Tropical Medicine and Rehabilitation Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia b School of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia article info abstract Article history: The parasitic nematode Ancylostoma ceylanicum is common in dogs, cats and humans throughout Asia, Received 19 February 2013 inhabiting the small intestine and possibly leading to iron-deficient anaemia in those infected. It has pre- Revised 23 April 2013 viously been discovered in domestic dogs in Australia and this is the first report of A. ceylanicum in wild Accepted 26 April 2013 canids. Wild dogs (dingoes and dingo hybrids) killed in council control operations (n = 26) and wild dog scats (n = 89) were collected from the Wet Tropics region around Cairns, Far North Queensland. All of the carcasses (100%) were infected with Ancylostoma caninum and three (11.5%) had dual infections with A. Keywords: ceylanicum. Scats, positively sequenced for hookworm, contained A. ceylanicum, A. caninum and Ancylos- Ancylostoma ceylanicum toma braziliense, with A. ceylanicum the dominant species in Mount Windsor National Park, with a prev- Dingo Canine alence of 100%, but decreasing to 68% and 30.8% in scats collected from northern and southern rural Hookworm suburbs of Cairns, respectively. -

Two New Species of Gaeolaelaps (Acari: Mesostigmata: Laelapidae)

Zootaxa 3861 (6): 501–530 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3861.6.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:60747583-DF72-45C4-AE53-662C1CE2429C Two new species of Gaeolaelaps (Acari: Mesostigmata: Laelapidae) from Iran, with a revised generic concept and notes on significant morphological characters in the genus SHAHROOZ KAZEMI1, ASMA RAJAEI2 & FRÉDÉRIC BEAULIEU3 1Department of Biodiversity, Institute of Science and High Technology and Environmental Sciences, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, Kerman, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Gorgan, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] 3Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling avenue, Ottawa, ON K1A 0C6, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two new species of laelapid mites of the genus Gaeolaelaps Evans & Till are described based on adult females collected from soil and litter in Kerman Province, southeastern Iran, and Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Gaeolaelaps jondis- hapouri Nemati & Kavianpour is redescribed based on the holotype and additional specimens collected in southeastern Iran. The concept of the genus is revised to incorporate some atypical characters of recently described species. Finally, some morphological attributes with -

Partial Report of Activities Carried out in the Masako Forest Reserve

PARTIAL REPORT OF ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT IN THE MASAKO FOREST RESERVE PROJECT ID: 27590-1 By Franck Masudi Muenye Mali May 2019 The project is funded by the Rufford Foundation “Amphibian diversity and environmental education for local people and capacity building for decision makers for the survival of Masako Forest Reserve in the DRC” PROJECT ID: 27590-1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. FIELD METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Investigation ............................................................................................................................ 3 2.2. Amphibian inventory .................................................................................................................... 4 3. PRELIMINARY RESULTS .................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. Views and proposals collected from the local community on the destruction of the Masako forest reserve ...................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1.1. Summary of responses to questions submitted to the local community ....................... 5 3.1.2. Immediate consequences observed following the destruction of the Masako reserve . 5 3.2. List of direct consequences -

On Predation in Epicriidae (Gamasida, Anactinotrichida) and Fine- Structural Details of Their Forelegs

SOIL ORGANISMS Volume 82 (2) August 2010 pp. 179–192 ISSN: 1864 - 6417 On predation in Epicriidae (Gamasida, Anactinotrichida) and fine- structural details of their forelegs Gerd Alberti Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald, J.-S.-Bach-Str. 11/12, 17489 Greifswald, Germany; Tel.: +49 38351-305; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The present study reveals, based on video-recording, that Epicriidae are predators using their long forelegs provided with a number of long clubbed setae for the capture of small arthropods. The mite walks slowly with raised and probing forelegs. Upon contact with a small isotomid springtail, the forelegs rapidly touch the prey with the tips of the elongated, clubbed setae. The prey evidently adheres to these setae and is drawn back to the mouthparts. The epicriid feeds for a considerable time on its prey whereby the mite can move around until it finds a shelter. The clubs represent spinose setal ends which are loaded with a granular secretion. The origin of the secretion could not yet be clarified definitely. Since the setae contain a lumen it might be that the secretion reaches the club through the seta. The secretion which covers the surface of the mite as a cerotegument is fine structurally distinctly different and is most likely produced by typical anactinotrichid dermal glands, which also occur in the forelegs. Some details of the fine structure of legs I are demonstrated. Since these clubbed setae occur in all Epicriidae it seems likely that all are predators feeding on small, weakly sclerotised arthropods. Keywords: adhesive setae, dermal glands, mites, sensory setae, video recording 1. -

The Endangered Butterfly Charonias Theano (Boisduval)(Lepidoptera

Neotropical Entomology ISSN: 1519-566X journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ne ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND BIONOMICS The Endangered Butterfly Charonias theano (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae): Current Status, Threats and its Rediscovery in the State of São Paulo, Southeastern Brazil AVL Freitas1, LA Kaminski1, CA Iserhard1, EP Barbosa1, OJ Marini Filho2 1 Depto de Biologia Animal & Museu de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Univ Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brasil 2Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação do Cerrado e Caatinga – CECAT, Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Brasília, DF, Brasil Keywords Abstract Aporiina, Atlantic Forest, endangered species, Pierini, Serra do Japi The pierid Charonias theano Correspondence (Boisduval), an endangered butterfly André V L Freitas, Depto de Biologia Animal & species, has been rarely observed in nature, and has not been recorded Museu de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Univ in the state of CSão. theano Paulo in the last 50 years despite numerous efforts Estadual de Campinas, CP6109, 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brasil; [email protected] to locate extant colonies. Based on museum specimens and personal information, was known from 26 sites in southeastern Edited by Kleber Del Claro – UFU and southern Brazil. Recently, an apparently viable population was recorded in a new locality, at Serra do Japi, Jundiaí, São Paulo, with Received 26 May 2011 and accepted 03 severalsince this individuals site represents observed one of during the few two large weeks forested in April, protected 2011. areas The August 2011 existence of this population at Serra do Japi is an important finding, São Paulo, but within its entire historical distribution. where the species could potentially persist not only in the state of Introduction In the last Brazilian red list of endangered fauna (Machado intensively sampled from 1987 to 1991, resulting in a list et al of 652 species (Brown 1992). -

The Impact of Edge Effect on Termite Community (Blattodea: Isoptera) in Fragments of Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest C

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.17815 Original Article The impact of edge effect on termite community (Blattodea: Isoptera) in fragments of Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest C. S. Almeidaa,b, P. F. Cristaldob, D. F. Florencioc, E. J. M. Ribeirob, N. G. Cruza,b, E. A. Silvad, D. A. Costae and A. P. A. Araújob* aPrograma de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Conservação, Universidade Federal de Sergipe – UFS, Av. Marechal Rondon, s/n, Jardim Rosa Elze, CEP 49100-000, São Cristóvão, SE, Brazil bLaboratório de Interações Ecológicas, Departamento de Ecologia, Universidade Federal de Sergipe – UFS, Av. Marechal Rondon, s/n, Jardim Rosa Elze, CEP 49100-000, São Cristóvão, SE, Brazil cDepartamento de Agrotecnologia e Ciências Sociais, Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido – UFERSA, BR 110, Km 47, Bairro Pres. Costa e Silva, CP 137, CEP 59625-900, Mossoró, RN, Brazil dPrograma de Pós-graduação em Ciências Ambientais, Universidade Federal de Rondônia – UNIR, Av. Norte Sul, 7300, Bairro Nova Morada, CEP 76940-000, Rolim de Moura, RO, Brazil eDepartamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso – UNEMAT, Rod. MT. 358, Km 07, Jd. Aeroporto, CEP 78300-000, Tangará da Serra, MT, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: October 29, 2015 – Accepted: April 13, 2016 – Distributed: August 31, 2017 (With 1 figure) Abstract Habitat fragmentation is considered to be one of the biggest threats to tropical ecosystem functioning. In this region, termites perform an important ecological role as decomposers and ecosystem engineers. In the present study, we tested whether termite community is negatively affected by edge effects on three fragments of Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest.