Dismantling the Myth of ‘

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Mystici Corporis Christi

MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE MISTICAL BODY OF CHRIST TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN, PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES ENJOYING PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE June 29, 1943 Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church,[1] was first taught us by the Redeemer Himself. Illustrating as it does the great and inestimable privilege of our intimate union with so exalted a Head, this doctrine by its sublime dignity invites all those who are drawn by the Holy Spirit to study it, and gives them, in the truths of which it proposes to the mind, a strong incentive to the performance of such good works as are conformable to its teaching. For this reason, We deem it fitting to speak to you on this subject through this Encyclical Letter, developing and explaining above all, those points which concern the Church Militant. To this We are urged not only by the surpassing grandeur of the subject but also by the circumstances of the present time. 2. For We intend to speak of the riches stored up in this Church which Christ purchased with His own Blood, [2] and whose members glory in a thorn-crowned Head. The fact that they thus glory is a striking proof that the greatest joy and exaltation are born only of suffering, and hence that we should rejoice if we partake of the sufferings of Christ, that when His glory shall be revealed we may also be glad with exceeding joy. -

The Mediation of the Church in Some Pontifical Documents Francis X

THE MEDIATION OF THE CHURCH IN SOME PONTIFICAL DOCUMENTS FRANCIS X. LAWLOR, SJ. Weston College N His recent encyclical letter, Hurnani generis, of Aug. 12, 1950, the I Holy Father reproves those who "reduce to a meaningless formula the necessity of belonging to the true Church in order to achieve eternal salvation."1 In the light of the Pope's insistence in the same encyclical letter on the ordinary, day-by-day teaching office of the Roman Pontiffs, it will be useful to select from the infra-infallible but authentic teaching of the Popes some of the abundant material touching the question of the mediatorial function of the Church in the order of salvation. The Popes, to be sure, do not speak and write after the manner of theo logians but as pastors of souls, and it is doubtless not always easy to transpose to a theological level what is contained in a pastoral docu ment and expressed in a pastoral method of approach. Yet the authentic teaching of the Popes is both a guide to, and a source of, theological thinking. The documents cited are of varying solemnity and doctrinal importance; an encyclical letter is clearly of greater magisterial value than, let us say, an occasional epistle to some prelate. It is not possible here to situate each citation in its documentary context; but the force and point of a quotation, removed from its documentary perspective, is perhaps as often lessened as augmented. Those who wish may read them in their context, if they desire a more careful appraisal of evidence. -

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents Introduction: When reviewing Angelo Roncalli's activities in favor of the Jewish people across many years, one may distinguish three parts; the first, during the years 1940-1944, when he served as Apostolic Delegate of the Vatican in Istanbul, Turkey, with responsibility over the Balkan region. The second, as a Nuncio in France, in 1947, on the eve of the United Nations decision on the creation of a Jewish state. Finally, in 1963, as Pope John XXIII, when he brought about a radical positive change in the Church's position of the Jewish people. 1) As the Apostolic Delegate in Istanbul, during the Holocaust years, Roncalli aided in various ways Jewish refugees who were in transit in Turkey, including facilitating their continued migration to Palestine. His door was always open to the representatives of Jewish Palestine, and especially to Chaim Barlas, of the Jewish Agency, who asked for his intervention in the rescue of Jews. Among his actions, one may mention his intervention with the Slovakian government to allow the exodus of Jewish children; his appeal to King Boris II of Bulgaria not to allow his country's Jews to be turned over to the Germans; his consent to transmit via the diplomatic courier to his colleague in Budapest, the Nuncio Angelo Rotta, various documents of the Jewish Agency, in order to be further forwarded to Jewish operatives in Budapest; valuable documents to aid in the protection of Jews who were authorized by the British to enter Palestine. Finally, above all -- his constant pleadings with his elders in the Vatican to aid Jews in various countries, who were in danger of deportation by the Nazis. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

'Owned' Vatican Guilt for the Church's Role in the Holocaust?

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Madigan CP 1-18 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Has the Papacy ‘Owned’ Vatican Guilt for the Church’s Role in the Holocaust? Kevin Madigan Harvard Divinity School Plenary presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Council of Centers on Christian-Jewish Relations November 1, 2009, Florida State University, Boca Raton, Florida Given my reflections in this presentation, it is perhaps appropriate to begin with a confession. What I have written on the subject of the papacy and the Shoah in the past was marked by a confidence and even self-righteousness that I now find embarrassing and even appalling. (Incidentally, this observation about self-righteousness would apply all the more, I am afraid, to those defenders of the wartime pope.) In any case, I will try and smother those unfortunate qualities in my presentation. Let me hasten to underline that, by and large, I do not wish to retract conclusions I have reached, which, in preparation for this presentation, have not essentially changed. But I have come to perceive much more clearly the need for humility in rendering judgment, even harsh judgment, on the Catholic actors, especially the leading Catholic actors of the period. As José Sanchez, with whose conclusions in his book on understanding the controversy surrounding the wartime pope I otherwise largely disagree, has rightly pointed out, “it is easy to second guess after the events.”1 This somewhat uninflected observation means, I take it, that, in the case of the Holy See and the Holocaust, the calculus of whether to speak or to act was reached in the cauldron of a savage world war, wrought in the matrix of competing interests and complicated by uncertainty as to whether acting or speaking would result in relief for or reprisal. -

Godność Człowieka I Dobro Wspólne W Papieskim Nauczaniu Społecznym

Rozdział III Godność człowieka i dobro wspólne w nauczaniu papieskim w latach 1878−1958 1. Leon XIII i fundamenty papieskiego nauczania o godności człowieka i dobru wspólnym Nikomu nie wolno naruszać bezkarnie tej godności człowie- ka, którą sam Bóg z wielka czcią rozporządza899. Cel bowiem wytknięty państwu dotyczy wszystkich oby- wateli, bo jest nim dobro powszechne, w którym uczestni- czyć mają prawo wszyscy razem i każdy z osobna, w części należnej900. Uczestnicy współczesnego dyskursu politycznego w poszukiwaniu aksjologicznych fun- damentów dla ustawodawstwa krajowego czy ponadnarodowego odwołują się do takich kategorii, jak: wolność, równość, prawa człowieka. Do tych fundamentalnych idei zaliczyć należy również dignitas humana i bonum commune901. Wydaje się poza dyskusją, że wielką rolę w przetrwaniu i rozwoju tych idei odegrała katolicka nauka społeczna, co uzasadnia poddanie analizie poglądów w tej materii twórcy papieskiego nauczania społecznego Le- ona XIII. Wybrany 20 lutego 1878 r. na papieża arcybiskup Perugii, kardynał Vincenzo Gioacchi- no Aloiso Pecci (1810−1903) przybrał imię Leona XIII. Nowy papież rozbudził w środowi- skach katolickich, zwłaszcza w kręgach zajmujących się problemami społecznymi, wielkie nadzieje na zmiany, które byłyby w stanie dostosować Kościół katolicki do istniejących 899 Rerum novarum Jego Świątobliwości Leona, z opatrzności Bożej papieża XIII, encyklika o robot- nikach z 15 maja 1891 r. Osobne odbicie z „Notyfi kacyj” Kuryi Książęco-Biskupiej w Krakowie, nr VII i VIII z roku 1891, Kraków 1891, s. 27. 900 Ibidem, s. 33. 901 Szerzej na ten temat por. M. Sadowski, Godność człowieka – aksjologiczna podstawa państwa i prawa, [w:] Studia Erasmiana Wratislaviensia − Wrocławskie Studia Erazmiańskie, Zeszyt Naukowy Studentów, Doktorantów i Pracowników Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, Wrocław 2007, s. -

The Lateran Pacts and the Debates in the Italian Constituent Assembly with Reference to Religious Freedom, and the Consequences for Religious Minorities (1946-1948)

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The Lateran Pacts and the debates in the Italian Constituent Assembly with reference to religious freedom, and the consequences for religious minorities (1946-1948). Thomas, Huw Martin How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Huw Martin (2005) The Lateran Pacts and the debates in the Italian Constituent Assembly with reference to religious freedom, and the consequences for religious minorities (1946-1948).. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43092 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

G L O S S a R Y O F T E R

GLOSSARY OF TERMS ● anti-Judaism: hostility toward the Jewish religion, usually based on Christian theological principles. ● antisemitism: term created in 1879 by Wilhelm Marr in Germany. Jews were defined as a distinct “race”; a contemporary name for “Jew-hatred” or “Judeophobia.” ● Black Nobility: the papal aristocracy who remained loyal to the Holy See after the abolition of the papal states in 1870. ● congregation: a Vatican department supervising a specific part of church government: for example, Congregation for the Sacraments supervised the liturgical life of the church. ● Curia: the governing body of the Catholic Church. ● deicide: literally “the murder of God”; a charge levelled against the Jews by many of the Church Fathers. Officially rejected by the Catholic Church in 1965. ● dicastery: subsection of a congregation. ● Diocese: geographical region governed by a bishop. ● diplomatic note: a less formal communication between governments. ● encyclical: formal papal letter addressed to the whole church or, in special cases, addressed to a particular country, specifying an area of Catholic faith and morals. ● Endlösung: The “Final Solution”; Nazi euphemism for the murder of the Jews. It was the “Final Solution” of the Judenfrage (the Jewish question). ● Holy See: the seat of the bishop of Rome, the symbol of unity within the Catholic Church. Often used interchangeably with Vatican. ● Holy Week: most sacred week in the Christian calendar stretching from Palm Sunday through to the Easter Triduum (Holy or Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday, Easter Sunday). It recalls the last days of Christ and is marked with liturgies of special solemnity. ● legate: papal representative in a country without formal diplomatic relations with the Holy See. -

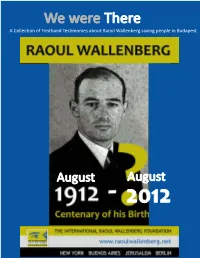

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27