Messiaen's Rhythmical Organisation and Classical Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdsong in the Music of Olivier Messiaen a Thesis Submitted To

P Birdsongin the Music of Olivier Messiaen A thesissubmitted to MiddlesexUniversity in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy David Kraft School of Art, Design and Performing Arts Nfiddlesex University December2000 Abstract 7be intentionof this investigationis to formulatea chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'streatment of birdsong,taking into accountthe speciesinvolved and the composer'sevolving methods of motivic manipulation,instrumentation, incorporation of intrinsic characteristicsand structure.The approachtaken in this studyis to surveyselected works in turn, developingappropriate tabular formswith regardto Messiaen'suse of 'style oiseau',identified bird vocalisationsand eventhe frequentappearances of musicthat includesfamiliar characteristicsof bird style, althoughnot so labelledin the score.Due to the repetitivenature of so manymotivic fragmentsin birdsong,it has becomenecessary to developnew terminology and incorporatederivations from other research findings.7be 'motivic classification'tables, for instance,present the essentialmotivic featuresin somevery complexbirdsong. The studybegins by establishingthe importanceof the uniquemusical procedures developed by Messiaen:these involve, for example,questions of form, melodyand rhythm.7he problemof is 'authenticity' - that is, the degreeof accuracywith which Messiaenchooses to treat birdsong- then examined.A chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'suse of birdsongin selectedmajor works follows, demonstratingan evolutionfrom the ge-eralterm 'oiseau' to the preciseattribution -

Aspects of Structure in Olivier Messiaen's Vtngt Regards Sur L'enfant-Jesus

ASPECTS OF STRUCTURE IN OLIVIER MESSIAEN'S VTNGT REGARDS SUR L'ENFANT-JESUS by DAVID ROGOSIN B.Mus., l'Universite de Montreal, 1978 M.Mus., l'Universite de Montreal, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 1996 © David Rogosin, 1996 AUTHORIZATION In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ASPECTS OF STRUCTURE IN OLIVIER MESSIAEN'S "VINGT REGARDS SUR L'ENFANT-JESUS" ABSTRACT The paper explores various structural aspects of the 1944 masterwork for piano, Vingt Regards sur I'Enfant-Jesus, by Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992). Part One examines elements of the composer's style in isolation, focusing prin• cipally on the use of the modes of limited transposition to generate diverse tonal styles, as well as the use of form and "cyclical" or recurring themes and motifs to both unify and diversify the work. -

Messiaen's Influence on Post-War Serialism Thesis

3779 N8! RI. oIo MESSIAEN'S INFLUENCE ON POST-WAR SERIALISM THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Thomas R. Muncy, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1984 Muncy, Thomas R., Messiaen's Influence on Post-'gar Serialism. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1984, 106 pp., 76 examples, biblio- graphy, 44 titles. The objective of this paper is to show how Olivier Messiaen's Mode de valeurs et d'intensites influenced the development of post- war serialism. Written at Darmstadt in 1949, Mode de valeurs is considered the first European work to organize systematically all the major musical parameters: pitch, duration, dynamics, articulation, and register. This work was a natural step in Messiaen's growth toward complete or nearly complete systemization of musical parameters, which he had begun working towards in earlier works such as Vingt regards sur 1'Enfant-Jesus (1944), Turangalila-symphonie (1946-8), and Cantyodjaya (1949), and which he continued to experiment with in later works such as Ile de Feu II (1951) and Livre d'orgue (1951). The degree of systematic control that Messiaen successfully applied to each of the musical parameters influenced two of the most prominent post-war serial composers, Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, to further develop systematic procedures in their own works. This paper demonstrates the degree to which both Boulez' Structures Ia (1951) and Stockhausen's Kreuzspiel (1951) used Mode de valeurs as a model for the systematic organization of musical parameters. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF EXAMPLES..-.........-... -

A Musical and Theological Discussion of Olivier Messiaen’S Vingt Regards Sur L’Enfant-Jésus

The Theme of God: A Musical and Theological Discussion of Olivier Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus By © 2017 Heekyung Choi Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Kirkendoll ________________________________ Dr. Richard Reber ________________________________ Dr. Scott Murphy ________________________________ Dr. Scott McBride Smith ________________________________ Dr. Jane Barnette Date Defended: 1 May 2017 The Dissertation Committee for Heekyung Choi certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Theme of God: A Musical and Theological Discussion of Olivier Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Kirkendoll Date approved: 1 May 2017 ii Abstract The purpose of this research is to help both performers and liturgical musicians to better understand Messiaen’s musical style and theological inspiration. Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) is one of the most important composers of French keyboard music in the twentieth century. He composed numerous works in nearly every musical genre, many inspired by his Catholic faith. Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus) is a two-hour masterpiece for solo piano written in 1944, and is one of the most significant of his works. The piece is constructed by using three main themes: the Thème de Dieu (Theme of God), Thème de l’étoile et de la Croix (Theme of the Star and of the Cross), and Thème d’accords (Theme of Chords). The “Theme of God” is based on an F-sharp major chord with chromatic passing tones in the inner voice. -

Messiaen Fiche

Histoire des esthétiques (crr_bordeaux) #7 Olivier Messiaen Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) - Repères Né d’un père professeur d’anglais et d’une mère poétesse, Olivier Messiaen acquiert jeune une foi catholique prononcée. Après ses premières leçons de piano et d’harmonie, il entre au Conservatoire de Paris en 1919, à 11 ans. Il a pour professeurs Maurice Emmanuel, Marcel Dupré, Paul Dukas, Charles-Marie Widor. En l’espace de six ans, il obtient des premiers prix en harmonie, fugue, contrepoint, accompagnement au piano, histoire de la musique, orgue, improvisation à l’orgue, et enfin composition. En 1931, Olivier Messiaen prend le poste d’organiste à l’église de la Trinité, à Paris. Il improvise, compose beaucoup, expérimente ses idées musicales, inspirées par le plain-chant, les rythmes anciens et asiatiques, et les chants des oiseaux qui le fascinent – il décide même de devenir ornithologue. Il commence à enseigner en 1934, à l’Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris et à la Schola Cantorum. Il devient professeur d’harmonie au Conservatoire en 1942, après la Seconde guerre mondiale, durant laquelle il est fait prisonnier et compose son Quatuor pour la fin du temps. A cette période, il rencontre Yvonne Loriod, qui devient sa femme et l’interprète principale de ses œuvres pour piano. Progressivement, Olivier Messiaen se met à donner des cours d’analyse, d’esthétique, de rythme, au Conservatoire et à l’étranger. En 1966, sa classe d’analyse est instituée en tant que classe de composition. Elle attire des élèves du monde entier, parmi lesquels Pierre Boulez, Pierre Henry, George Benjamin, Karlheinz Stockhausen ou encore Iannis Xenakis. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Oliver Messiaen: Structural aspects of the pianoforte music Macdougall, Ian C. How to cite: Macdougall, Ian C. (1972) Oliver Messiaen: Structural aspects of the pianoforte music, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10211/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk OLIVIER MESSlAEN : STRUCTURAL ASPECTS OF THE PIANOFORTE MUSIC by IAN C. MACDOUGALL B. Mus. (Hons.) A Thesis presented for the Degree of : Master" of A~rts ! to the ' Faculty of Music at the University, of Durham. Durham, Glasgow & Dunblane 1st September, 1971. V • 1 v Olivier Messiaen .TABLE OF CONTENTS Frontispiece : Olivier Messiaen Summary Declaration of Originality Table of Acknowledgements Preface Chapter 1 Preliminary survey : An introduction to Messiaen's style, creed and musical language. Chapter 2 The 'Preludes' of 1929 and their importance in a continuing line of development. -

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA LAUNCHES MESSIAEN CELEBRATIONS a Major Festival to Celebrate the 100 Th Anniversary of the Composer’S Birth

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA LAUNCHES MESSIAEN CELEBRATIONS A major festival to celebrate the 100 th Anniversary of the composer’s birth The Philharmonia Orchestra is mounting a significant celebration of the 1 00th Annive rsary of Messiaen’s birth (1908 -1992 ), from 4 February to 23 October . Esa -Pekka Salonen, who becomes Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor in September , conducts the first part in February with concerts in London, Basingstoke, Cardiff, Southend -on - Sea, Bari, Luxembourg, Parma and Palermo and featuring two iconic works : Messiaen’s Turangalîla -symphonie and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring . Both works are iconic pieces in Salonen’s own history; indeed Messiaen’s Turangal îla -symphonie was the piece th at inspired him to take up music. "I was about 11 and couldn't believe there was music like that… if that's what you could produce, I thought it must be the most fascinating thing on earth." The exploration of Messiaen’s work throughout the festival hig hlights the sheer range of the composer’s output from the chamber music ( Quatuor pour la fin du Temps ) to song cycles ( Poèmes pour Mi ), from works for solo piano and small ensemble ( Oiseaux exotiques ) to the two very gigantic but very different masterpiece s: Turangalîla -symphonie and La Transfiguration de Notre -Seigneur Jésus Christ. The Philharmonia is proud to bring together an array of performers who are not only the very finest exponents of Messiaen’s music, but who knew and admired him as a friend, tea cher or mentor : Pierre -Laurent Aimard, George Benjamin, Sylvain Cambreling, Roger Muraro, Cynthia Mill ar and Kent Nagano. -

Messiaen - L’Essentiel De L’Oeuvre Jacques Amblard

Messiaen - l’essentiel de l’oeuvre Jacques Amblard To cite this version: Jacques Amblard. Messiaen - l’essentiel de l’oeuvre. 2019. hal-02293601 HAL Id: hal-02293601 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02293601 Preprint submitted on 20 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Jacques Amblard (Aix-Marseille Université) Messiaen – L’essentiel de l’œuvre Ce texte est publié dans Brahms (encyclopédie en ligne de l’IRCAM, voit « Messiaen : parcours de l’œuvre »), mais dans une version considérablement réduite, et finalement nettement distincte de celle-ci. La musicographie a souvent dépeint le Messiaen catholique. On a beaucoup évoqué l’ornithologue passionné. Il est parfois question du « rythmicien », du goût pour les modes rythmiques du Moyen Âge, de l’Inde, pour les « rythmes non-rétrogradables », les « modes à transpositions limitées ». Or, tous ces discours reconduisent surtout ceux d’un musicologue célèbre : Messiaen lui- même, discours qu’il semble – de nos jours encore – difficile de contredire, voire simplement de compléter. Peter Hill et Nigel Simeone remarquent à la première page de leur ouvrage que « plus d’une décennie après sa mort, notre connaissance [de Messiaen] est toujours largement conditionnée par ce qu’il a dit de lui-même ». -

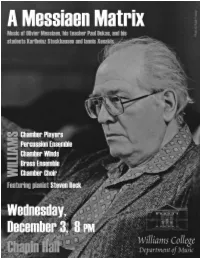

12-3 Massaen Matrix Program

PROGRAM Paul Dukas Fanfare pour preceder La Péri (1912) (1865-1935) Olivier Messiaen “Les oiseaux de Karuizawa” (1908-1992) from Sept Haikai (1962) Karlheinz Stockhausen Refrain (1959) (1928-2007) Olivier Messiaen “Regard de la Vierge” from Vingt Regards sur l'Enfant Jesus (1944) Julian Mesri ’09, piano Olivier Messiaen O sacrum convivium! (1937) Eric Kang ’09, student conductor Olivier Messiaen from Petite esquisses d’oiseaux (1985) I. Le Rouge Gorge II. Le Merle Noir Tiffany Yu ’12, piano Iannis Xenakis Plektó (1993) (1922-2001) Olivier Messiaen Oiseaux exotiques (1956) ___________________________ No photography or recording without permission. Please turn off or mute cell phones, audible pagers, etc. PERFORMERS Chamber Choir Brad Wells, director Augusta Caso ’09 & Eric Kang ’09, student conductors Soprano Alto Tenor Baritone Chloe Blackshear ’10 Augusta Caso ’09 Eric Kang ’09 Chaz Lee ’11 Yanie Fecu ’10 Marni Jacobs ’12 Rob Silversmith ’11 Tim Lengel ’11 Sarah Riskind ’09 Devereux Powers ’10 Richard McDowell ’09 Katie Yosua ’11 Anna Scholtz ’09 Scott Smedinghoff ’09 Chamber Players/Chamber Winds/ Percussion Ensemble/Brass Ensemble Steven Dennis Bodner, Matthew Gold,Thomas Bergeron, directors Aaron Bauer ’11, tuba ∗ Susan Martula, clarinet ∼ξ Steve Beck, piano ∼ξ Lia McInerney ’12, piccolo ∼ Thomas Bergeron, trumpet ∗∼ξ Libby Miles ’09, bassoon ∼ Steven Bodner, conductor ∗∼ℵξ Elise Piazza ’09, Bb/Eb clarinets ℵξ Alex Creighton ’10, percussion ∼ξ Nina Piazza ’12, percussion ∼ξ Aaron Freedman ’12, clarinet ∼ Thomas Sikes ’11, trumpet -

AQA, Edexcel & OCR: Olivier Messiaen

KSKS55 AQA, Edexcel & OCR: Olivier Messiaen David Kettle is resources editor by David Kettle of Music Teacher magazine, and a journalist and writer on music with a special interest in WHY STUDY MESSIAEN? 20th- and 21st- century music. Olivier Messiaen was quite simply one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. As a teacher, he taught many of the figures who became giants in the post-war avant-garde – among them Boulez, Stockhausen and Xenakis. And as a composer, he sits on a line from Debussy to Boulez and beyond, creating music of such sensuality and religious devotion that we’re still coming to terms with it today. Perhaps that’s why his music inspires fervid devotion in some – and downright incredulity in others. In any case, encountering the works of Messiaen as part of a school course can have a transformative effect on students’ understanding of music’s power, can capture their imagination, and can provide entirely new ways of looking at music in terms of symbolism, colour, time and spirituality. Messiaen is included in three of the current KS5 specifications (detailed below), and his music can provide countless starting points for composing activites, a few ideas for which are also included in this resource. We’ll look at four key works from across Messiaen’s career – Le banquet céleste, the Quartet for the End of Time, the Turangalîla Symphony and Des canyons aux étoiles… – and examine key elements of Messiaen’s style that are apparent in each of them. AQA Messiaen is one of four named composers specified for study in AQA’s AoS7: Art music since 1910. -

Cycle Messiaen.Pdf

Série d'émissions sur l'œuvre d'Olivier Messiaen Témoignage du P.Jean Rodolphe Kars Liste des titres de cette série Télécharger la série Messiaen Ecouter Radio Espérance Cette série d'émissions, a été enregistrée en 1997 pour Radio Espérance. La qualité technique laisse parfois amplement à désirer, l'objectif de l'émission ayant été plutôt axé sur l'aspect pédagogique. En outre, les exemples musicaux sont donnés par le père Kars sur un synthétiseur de qualité très moyenne. On ne sera pas étonné de mentions d'événements maintenant passés (années préparatoires du Jubilé de l'an 2000 etc.), ce qui ne saurait diminuer l'intérêt global de l'émission. Ce cycle d'émissions est d'abord orienté vers un public de culture catholique. Ceci explique l'accent prépondérant mis sur la spiritualité mystique et théologique - par rapport à l'aspect purement musicologique - de l'œuvre d'Olivier Messiaen. PERE JEAN-RODOLPHE KARS Chapelain de Paray-le-Monial, Ancien Pianiste-Concertiste, Premier Prix du Concours de Piano Olivier Messiaen (1968), Conférencier du Festival Messiaen à l’Eglise de la Ste Trinité, Paris (1995). TEMOIGNAGE DU PERE Jean-Rodolphe KARS SUR L’ŒUVRE D’OLIVIER MESSIAEN Né en 1947 de parents juifs autrichiens non pratiquants, qui s'établirent en France en 1948, je commence le piano à sept ans, étudie au Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris, et commence une carrière en 1967, après avoir été finaliste au concours international de piano de Leeds (Angleterre). Renforcée par la réception du 1er prix du concours Olivier Messiaen, en 1968, ma carrière devient internationale. -

Messiaen, Saint Francis, and the Birds of Faith CHARLES H

Messiaen, Saint Francis, and the Birds of Faith CHARLES H. J. PELTZ I have been asked to deliver a confession of my faith, that is, to talk about what I believe, what I love, what I hope for. What do I believe? That doesn’t take long to say and in it everything is said at once: I believe in God. And because I believe in God I believe likewise in the Holy Trinity and [especially] the Holy Spirit.1 I have read that quotation many times and I am still astounded. I am astounded by the strength in its delivery and the personal submission in its substance. Olivier Messiaen offered it in 1971 to assembled dignitaries upon receipt of the Praemium Erasmianum, an honor acknowledging his status as an artist. Like the irresistible utterances of truth by Daniel to the Babylonians, Paul to the Corinthians, and Christ to the Pharisees, the words were out of fashion for both the moment and the era. As with his biblical predecessors, the career risks were high for a musician of his stature to openly proclaim God. His age was not one of sorting through conflicting passions about God’s truth. Rather it was a century of hoping that God would evaporate through disinterest, wherein musicians spent great energy denying the Gott of “Götterfunken.” A composer of some of the twentieth century’s most important works, Messiaen was both a giant of music and a devout Christian Catholic apologist. His was a highly original voice marked by an extraordinary use of time and its active offspring, rhythm, and a use of color more vivid than one could have imagined even with his French birthright of iridescent sound.