Pericles Coastal Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Sound of Arisaig (Loch Ailort to Loch Ceann Traigh) Sac

Conservation and Management Advice SOUND OF ARISAIG (LOCH AILORT TO LOCH CEANN TRAIGH) SAC MARCH 2021 This document provides advice to Public Authorities and stakeholders about the activities that may affect the protected features of Sound of Arisaig Special Area of Conservation (SAC). It provides advice from Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) (operating under the name of and hereinafter referred to as NatureScot) under Regulation 33(2) of the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994 (as amended in Scotland) to other relevant authorities about any activities/operations which may cause deterioration of the habitats or species, or disturbance of species protected in the SAC, and the Conservation Objectives for the site. It covers a range of different activities and developments but is not exhaustive. It focuses on where there is a risk to achieving the Conservation Objectives. The paper does not attempt to cover all possible future activities or eventualities (e.g. as a result of accidents), and does not consider cumulative effects. Further information on marine protected areas and management is available at - https://www.gov.scot/policies/marine-environment/marine-protected-areas/ For the full range of MPA site documents and more on the fascinating range of marine life to be found in Scotland’s seas, please visit - www.nature.scot/mpas or https://jncc.gov.uk/advice/marine-protected-areas/ Document version control Version Date Author Reason / Comments 1 01/08/2018 Laura Steel 1st draft. 2 09/03/2020 Sarah Review and edit. Cunningham 3 30/03/2020 Sarah Review of Corrina’s comments. Cunningham 4 31/03/2020 Emma Philip Review before sign-off 5 21/09/2020 Katherine Rebranding and text formatting Smailes Distribution list Format Version Issue date Issued to Electronic 1 09/03/2020 Corrina Mertens Electronic 2 31/03/2020 Greg Mudge and Chris Donald 2 Contents 1 OVERVIEW OF DOCUMENT ....................................................................................... -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons the Lords of the Isles and the Church

CHAPTER 5 Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons The Lords of the Isles and the Church Sarah Thomas Whilst the MacDonald contribution to the Church, and in particular to Iona, has been discussed, their involvement in the patronage of parish churches and secular clergy has up until now been neglected.1 This is an area of immense potential, given the surviving source material in the papal archives; through the study of clerical identities, building on the work of John Bannerman, we are able to identify connections between the clergy and the Lords of the Isles.2 The Lordship of the Isles incorporated two bishoprics, four monastic houses and approximately 64 parish churches of which the Lords had patronage of 41.3 In an age where the appropriation of parish churches to monastic and ecclesias- tical authorities was widespread, the Lordship’s patronage of so many parish churches meant that they had considerable influence over clerical careers and had significant scope to reward kindreds. However, that amount of control over ecclesiastical benefices might strain relations between lord and bishop. Relations with the monastic institutions were not always smooth either; a par- ticular issue was the admission of MacKinnons into the monastery of Iona. The Lordship lands lay within two dioceses; their lands in the Hebrides in the diocese of Sodor and their lands in Kintyre, Knapdale, Lochaber, Moidart, 1 Steer and Bannerman, Late Medieval Monumental Sculpture; Bannerman, ‘Lordship of the Isles’; M. MacGregor, ‘Church and Culture in the late medieval Highlands’ in J. Kirk (ed), The Church in the Highlands (Edinburgh, 1998); R.D. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010)

Department for Culture, Media and Sport Architecture and Historic Environment Division Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010) Compiled by English Heritage for the Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites. Text was also contributed by Cadw, Historic Scotland and the Environment and Heritage Service, Northern Ireland. s e vi a D n i t r a M © Contents ZONE ONE – Wreck Site Maps and Introduction UK Designated Shipwrecks Map ......................................................................................3 Scheduled and Listed Wreck Sites Map ..........................................................................4 Military Sites Map .................................................................................................................5 Foreword: Tom Hassall, ACHWS Chair ..........................................................................6 ZONE TWO – Case Studies on Protected Wreck Sites The Swash Channel, by Dave Parham and Paola Palma .....................................................................................8 Archiving the Historic Shipwreck Site of HMS Invincible, by Brandon Mason ............................................................................................................ 10 Recovery and Research of the Northumberland’s Chain Pump, by Daniel Pascoe ............................................................................................................... 14 Colossus Stores Ship? No! A Warship Being Lost? by Todd Stevens ................................................................................................................ -

Suibne Mac Cináeda from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

11/4/2015 4:33 PM https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suibne_mac_Cináeda Suibne mac Cináeda From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Suibne mac Cináeda (died 1034),[2] also known as Suibne mac Cinaeda,[3] Suibne mac Cinaedh,[4] and Suibhne mac Cináeda,[5][note 1] was an Suibne mac Cináeda eleventh-century ruler of the Gall Gaidheil, a population of mixed King of the Gall Gaidheil Scandinavian and Gaelic ethnicity. There is little known of Suibne, as he is only attested in three sources that record the year of his death. He seems to have ruled in a region where Gall Gaidheil are known to have dwelt: either the Hebrides, the Firth of Clyde region, or somewhere along the south- Suibne's name as it appears on folio 16v of Oxford western coast of Scotland from the firth southwards into Galloway. Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B 488 (the Annals of Tigernach).[1] Suibne's patronym, meaning "son of Cináed", could be evidence that he was a Died 1034 brother of the reigning Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Scotland, and thus a member of the royal Alpínid dynasty. Suibne's career appears to have Dynasty possibly Alpínid dynasty coincided with an expansion of the Gall Gaidheil along the south-west coast Father possibly Cináed mac Maíl Choluim of what is today Scotland. This extension of power may have partially contributed to the destruction of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, an embattled realm which then faced aggressions from Dublin Vikings, Northumbrians, and Scots as well. The circumstances of Suibne's death are unknown, although one possibility could be that he was caught up in the vicious dynastic-strife endured by the Alpínids. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

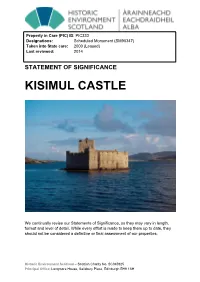

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c.