Influencers on Thyroid Cancer Onset: Molecular Genetic Basis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Genome-Wide Analysis of Host-Chromosome Binding Sites For

Lu et al. Virology Journal 2010, 7:262 http://www.virologyj.com/content/7/1/262 RESEARCH Open Access Genome-wide analysis of host-chromosome binding sites for Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) Fang Lu1, Priyankara Wikramasinghe1, Julie Norseen1,2, Kevin Tsai1, Pu Wang1, Louise Showe1, Ramana V Davuluri1, Paul M Lieberman1* Abstract The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein is required for the establishment of EBV latent infection in proliferating B-lymphocytes. EBNA1 is a multifunctional DNA-binding protein that stimulates DNA replication at the viral origin of plasmid replication (OriP), regulates transcription of viral and cellular genes, and tethers the viral episome to the cellular chromosome. EBNA1 also provides a survival function to B-lymphocytes, potentially through its ability to alter cellular gene expression. To better understand these various functions of EBNA1, we performed a genome-wide analysis of the viral and cellular DNA sites associated with EBNA1 protein in a latently infected Burkitt lymphoma B-cell line. Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) combined with massively parallel deep-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) was used to identify cellular sites bound by EBNA1. Sites identified by ChIP- Seq were validated by conventional real-time PCR, and ChIP-Seq provided quantitative, high-resolution detection of the known EBNA1 binding sites on the EBV genome at OriP and Qp. We identified at least one cluster of unusually high-affinity EBNA1 binding sites on chromosome 11, between the divergent FAM55 D and FAM55B genes. A con- sensus for all cellular EBNA1 binding sites is distinct from those derived from the known viral binding sites, sug- gesting that some of these sites are indirectly bound by EBNA1. -

Genotyping of Breech Flystrike Resource – Update

Project No: ON-00515 Contract No: PO4500010753 AWI Project Manager: Bridget Peachey Contractor Name: CSIRO Agriculture and Food Prepared by: Dr Sonja Dominik Publication Date: July 2019 Genotyping of breech flystrike resource – update Published by Australian Wool Innovation Limited, Level 6, 68 Harrington Street, THE ROCKS, NSW, 2000 This publication should only be used as a general aid and is not a substitute for specific advice. To the extent permitted by law, we exclude all liability for loss or damage arising from the use of the information in this publication. AWI invests in research, development, innovation and marketing activities along the global supply chain for Australian wool. AWI is grateful for its funding, which is primarily provided by Australian woolgrowers through a wool levy and by the Australian Government which provides a matching contribution for eligible R&D activities © 2019 Australian Wool Innovation Ltd. All rights reserved. Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction/Hypothesis .................................................................................................... 5 2 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 6 3 Project Objectives .............................................................................................................. 8 4 Success in Achieving Objectives ........................................................................................ -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

RET/PTC Activation in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

European Journal of Endocrinology (2006) 155 645–653 ISSN 0804-4643 INVITED REVIEW RET/PTC activation in papillary thyroid carcinoma: European Journal of Endocrinology Prize Lecture Massimo Santoro1, Rosa Marina Melillo1 and Alfredo Fusco1,2 1Istituto di Endocrinologia ed Oncologia Sperimentale del CNR ‘G. Salvatore’, c/o Dipartimento di Biologia e Patologia Cellulare e Molecolare, University ‘Federico II’, Via S. Pansini, 5, 80131 Naples, Italy and 2NOGEC (Naples Oncogenomic Center)–CEINGE, Biotecnologie Avanzate & SEMM, European School of Molecular Medicine, Naples, Italy (Correspondence should be addressed to M Santoro; Email: [email protected]) Abstract Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is frequently associated with RET gene rearrangements that generate the so-called RET/PTC oncogenes. In this review, we examine the data about the mechanisms of thyroid cell transformation, activation of downstream signal transduction pathways and modulation of gene expression induced by RET/PTC. These findings have advanced our understanding of the processes underlying PTC formation and provide the basis for novel therapeutic approaches to this disease. European Journal of Endocrinology 155 645–653 RET/PTC rearrangements in papillary growth factor, have been described in a fraction of PTC thyroid carcinoma patients (7). As illustrated in figure 1, many different genes have been found to be rearranged with RET in The rearranged during tansfection (RET) proto-onco- individual PTC patients. RET/PTC1 and 3 account for gene, located on chromosome 10q11.2, was isolated in more than 90% of all rearrangements and are hence, by 1985 and shown to be activated by a DNA rearrange- far, the most frequent variants (8–11). They result from ment (rearranged during transfection) (1).As the fusion of RET to the coiled-coil domain containing illustrated in Fig. -

Application of a MYC Degradation

SCIENCE SIGNALING | RESEARCH ARTICLE CANCER Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; Application of a MYC degradation screen identifies exclusive licensee American Association sensitivity to CDK9 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant for the Advancement of Science. No claim pancreatic cancer to original U.S. Devon R. Blake1, Angelina V. Vaseva2, Richard G. Hodge2, McKenzie P. Kline3, Thomas S. K. Gilbert1,4, Government Works Vikas Tyagi5, Daowei Huang5, Gabrielle C. Whiten5, Jacob E. Larson5, Xiaodong Wang2,5, Kenneth H. Pearce5, Laura E. Herring1,4, Lee M. Graves1,2,4, Stephen V. Frye2,5, Michael J. Emanuele1,2, Adrienne D. Cox1,2,6, Channing J. Der1,2* Stabilization of the MYC oncoprotein by KRAS signaling critically promotes the growth of pancreatic ductal adeno- carcinoma (PDAC). Thus, understanding how MYC protein stability is regulated may lead to effective therapies. Here, we used a previously developed, flow cytometry–based assay that screened a library of >800 protein kinase inhibitors and identified compounds that promoted either the stability or degradation of MYC in a KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line. We validated compounds that stabilized or destabilized MYC and then focused on one compound, Downloaded from UNC10112785, that induced the substantial loss of MYC protein in both two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cell cultures. We determined that this compound is a potent CDK9 inhibitor with a previously uncharacterized scaffold, caused MYC loss through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, and suppresses PDAC anchorage- dependent and anchorage-independent growth. We discovered that CDK9 enhanced MYC protein stability 62 through a previously unknown, KRAS-independent mechanism involving direct phosphorylation of MYC at Ser . -

RET Gene Fusions in Malignancies of the Thyroid and Other Tissues

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review RET Gene Fusions in Malignancies of the Thyroid and Other Tissues Massimo Santoro 1,*, Marialuisa Moccia 1, Giorgia Federico 1 and Francesca Carlomagno 1,2 1 Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnology, University of Naples “Federico II”, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (F.C.) 2 Institute of Endocrinology and Experimental Oncology of the CNR, 80131 Naples, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 March 2020; Accepted: 12 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Abstract: Following the identification of the BCR-ABL1 (Breakpoint Cluster Region-ABelson murine Leukemia) fusion in chronic myelogenous leukemia, gene fusions generating chimeric oncoproteins have been recognized as common genomic structural variations in human malignancies. This is, in particular, a frequent mechanism in the oncogenic conversion of protein kinases. Gene fusion was the first mechanism identified for the oncogenic activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase RET (REarranged during Transfection), initially discovered in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). More recently, the advent of highly sensitive massive parallel (next generation sequencing, NGS) sequencing of tumor DNA or cell-free (cfDNA) circulating tumor DNA, allowed for the detection of RET fusions in many other solid and hematopoietic malignancies. This review summarizes the role of RET fusions in the pathogenesis of human cancer. Keywords: kinase; tyrosine kinase inhibitor; targeted therapy; thyroid cancer 1. The RET Receptor RET (REarranged during Transfection) was initially isolated as a rearranged oncoprotein upon the transfection of a human lymphoma DNA [1]. -

RET Aberrations in Diverse Cancers: Next-Generation Sequencing of 4,871 Patients Shumei Kato1, Vivek Subbiah2, Erica Marchlik3, Sheryl K

Published OnlineFirst September 28, 2016; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1679 Personalized Medicine and Imaging Clinical Cancer Research RET Aberrations in Diverse Cancers: Next-Generation Sequencing of 4,871 Patients Shumei Kato1, Vivek Subbiah2, Erica Marchlik3, Sheryl K. Elkin3, Jennifer L. Carter3, and Razelle Kurzrock1 Abstract Purpose: Aberrations in genetic sequences encoding the tyrosine (52/88)], cell cycle–associated genes [39.8% (35/88)], the PI3K kinase receptor RET lead to oncogenic signaling that is targetable signaling pathway [30.7% (27/88)], MAPK effectors [22.7% with anti-RET multikinase inhibitors. Understanding the compre- (20/88)], or other tyrosine kinase families [21.6% (19/88)]. hensive genomic landscape of RET aberrations across multiple RET fusions were mutually exclusive with MAPK signaling cancers may facilitate clinical trial development targeting RET. pathway alterations. All 72 patients harboring coaberrations Experimental Design: We interrogated the molecular portfolio had distinct genomic portfolios, and most [98.6% (71/72)] of 4,871 patients with diverse malignancies for the presence of had potentially targetable coaberrations with either an FDA- RET aberrations using Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amend- approved or an investigational agent. Two cases with lung ments–certified targeted next-generation sequencing of 182 or (KIF5B-RET) and medullary thyroid carcinoma (RET M918T) 236 gene panels. thatrespondedtoavandetanib(multikinase RET inhibitor)- Results: Among diverse cancers, RET aberrations were iden- containing regimen are shown. tified in 88 cases [1.8% (88/4, 871)], with mutations being Conclusions: RET aberrations were seen in 1.8% of diverse the most common alteration [38.6% (34/88)], followed cancers, with most cases harboring actionable, albeit dis- by fusions [30.7% (27/88), including a novel SQSTM1-RET] tinct, coexisting alterations. -

Identification and Characterization of RET Fusions in Advanced Colorectal Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 6, No. 30 Identification and characterization of RET fusions in advanced colorectal cancer Anne-France Le Rolle1,2,*, Samuel J. Klempner1,2,*, Christopher R. Garrett3, Tara Seery1,2, Eric M. Sanford4, Sohail Balasubramanian4, Jeffrey S. Ross4,5, Philip J. Stephens4, Vincent A. Miller4, Siraj M. Ali4 and Vi K. Chiu1,2 1 Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA 2 Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California Irvine, Orange, CA, USA 3 The Division of Cancer Medicine, Department of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA 4 Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA 5 Albany Medical College, Albany, NY, USA * These authors have contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: Vi K. Chiu, email: [email protected] Keywords: RET fusion kinase, RET kinase inhibitor, comprehensive genomic profiling, colorectal cancer Received: April 02, 2015 Accepted: May 12, 2015 Published: May 30, 2015 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT There is an unmet clinical need for molecularly directed therapies available for metastatic colorectal cancer. Comprehensive genomic profiling has the potential to identify actionable genomic alterations in colorectal cancer. Through comprehensive genomic profiling we prospectively identified 6 RET fusion kinases, including two novel fusions of CCDC6-RET and NCOA4-RET, in metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. RET fusion kinases represent a novel class of oncogenic driver in CRC and occurred at a 0.2% frequency without concurrent driver mutations, including KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA or other fusion tyrosine kinases. -

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Innate Immune Kinase

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS UNDERLYING INNATE IMMUNE KINASE TBK1-DRIVEN ONCOGENIC TRANSFORMATION APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Michael A White, Ph.D. Melanie H. Cobb, Ph.D. Lawrence Lum, Ph.D. John D. Minna, M.D. DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my mother and Arlene for their love and support. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to my mentor, Dr. Michael White, for his continuous support and guidance through the entire study. I really appreciate his inspiration, patience, and generosity. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Cobb, Dr. Lum, and Dr. Minna, for their invaluable advice and discussion. I thank all the White lab members and my friends for their help, suggestion, and discussion. Particularly, I would like to thank Rosie, Michael, Brian, Tzuling, and Malia for their long-term support and collaboration. I would also like to thank my friends, Veleka, Pei-Ling, Jen-Chieh, Shu-Yi, Chih-Chiang, Jen-Shuan, Yi-Chun, and Yu-San for their friendship. I am grateful to Drs. Rolf Brekken, Zhijian James Chen, Xuetao Cao, Philip Tsichlis, Charles Yeaman, William Hahn, Keqiang Ye, and Shu-Chan Hsu, Bing Su, Dos Sarbassov, Mark Magnuson, David Sabatini, Thomas Tan, and Bert Vogelstein for many of the reagents used in these studies. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my mother and Arlene for their unending support and encouragement. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS UNDERLYING INNATE IMMUNE KINASE TBK1-DRIVEN ONCOGENIC TRANSFORMATION by YI-HUNG OU DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Dallas, Texas April, 2013 Copyright by YI-HUNG OU, 2013 All Rights Reserved MOLECULAR MECHANISMS UNDERLYING INNATE IMMUNE KINASE TBK1-DRIVEN ONCOGENIC TRANSFORMATION Publication No. -

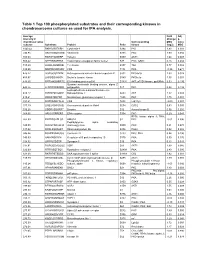

Table 1 Top 100 Phosphorylated Substrates and Their Corresponding Kinases in Chondrosarcoma Cultures As Used for IPA Analysis

Table 1 Top 100 phosphorylated substrates and their corresponding kinases in chondrosarcoma cultures as used for IPA analysis. Average Fold Adj intensity in Change p- chondrosarcoma Corresponding MSC value cultures Substrate Protein Psite kinase (log2) MSC 1043.42 RKKKVSSTKRH Cytohesin-1 S394 PKC 1.83 0.001 746.95 RKGYRSQRGHS Vitronectin S381 PKC 1.00 0.056 709.03 RARSTSLNERP Tuberin S939 AKT1 1.64 0.008 559.42 SPPRSSLRRSS Transcription elongation factor A-like1 S37 PKC; GSK3 0.18 0.684 515.29 LRRSLSRSMSQ Telethonin S157 Titin 0.77 0.082 510.00 MQPDNSSDSDY CD5 T434 PKA -0.35 0.671 476.27 GGRGGSRARNL Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K S302 PKCdelta 1.03 0.028 455.97 LKPGSSHRKTK Bruton's tyrosine kinase S180 PKCbeta 1.55 0.001 444.65 RRRMASMQRTG E1A binding protein p300 S1834 AKT; p70S6 kinase; pp90Rsk 0.53 0.195 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha Z 440.26 HLRSESQRQRR polypeptide S27 PKC 0.88 0.199 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6- 424.12 RPRNYSVGSRP biphosphatase 2 S483 AKT 1.32 0.003 419.61 KKKIATRKPRF Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 T695 PKC 1.75 0.001 391.21 DNSSDSDYDLH CD5 T453 Lck; Fyn -2.09 0.001 377.39 LRQLRSPRRAQ Ras associated protein Rab4 S204 CDC2 0.63 0.091 376.28 SSQRVSSYRRT Desmin S12 Aurora kinase B 0.56 0.255 369.05 ARIGGSRRERS EP4 receptor S354 PKC 0.29 0.543 RPS6 kinase alpha 3; PKA; 367.99 EPKRRSARLSA HMG14 S7 PKC -0.01 0.996 Peptidylglycine alpha amidating 349.08 SRKGYSRKGFD monooxygenase S930 PKC 0.21 0.678 347.92 RRRLSSLRAST Ribosomal protein S6 S236 PAK2 0.02 0.985 346.84 RSNPPSRKGSG Connexin -

The Clinical Utility of Optical Genome Mapping for the Assessment of Genomic Aberrations in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

cancers Article The Clinical Utility of Optical Genome Mapping for the Assessment of Genomic Aberrations in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Jonathan Lukas Lühmann 1,† , Marie Stelter 1,†, Marie Wolter 1, Josephine Kater 1, Jana Lentes 1, Anke Katharina Bergmann 1, Maximilian Schieck 1 , Gudrun Göhring 1, Anja Möricke 2, Gunnar Cario 2, Markéta Žaliová 3 , Martin Schrappe 2, Brigitte Schlegelberger 1, Martin Stanulla 4 and Doris Steinemann 1,* 1 Department of Human Genetics, Hannover Medical School, 30625 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] (J.L.L.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (M.W.); [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (A.K.B.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (B.S.) 2 Department of Pediatrics I, ALL-BFM Study Group, Christian-Albrechts University Kiel and University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, 24105 Kiel, Germany; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (M.S.) 3 Department of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and University Hospital Motol, CZ-15006 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Hannover Medical School, 30625 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors equally contributed to this work. Citation: Lühmann, J.L.; Stelter, M.; Wolter, M.; Kater, J.; Lentes, J.; Bergmann, A.K.; Schieck, M.; Simple Summary: The stratification of childhood ALL is currently based on various diagnostic Göhring, G.; Möricke, A.; Cario, G.; assays.