What's Inside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology of the River Cooter, Pseudemys Concinna, in a Southern Illinois Floodplain Lake

He!peto!ogica! Nalllral Historv, 5(2), 1997, pages 135-145. 135 ©1997 by the International Herpetological Symposium. Inc. ECOLOGY OF THE RIVER COOTER, PSEUDEMYS CONCINNA, IN A SOUTHERN ILLINOIS FLOODPLAIN LAKE Michael J. Dreslikl Department of Zoology, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois 61920, USA Abstract. In Illinois, the river cooter, Pseudemys concinna. is a poorly studied endangered species. During 1994-1996. I quantified growth, population size and structure. and diet of a population from a floodplain lake in Gallatin County, Illinois. For males and females. growth slowed between 8-15 and 13-24 years, respectively. Comparisons between male and female curves revealed that growth parameters and proportional growth toward the asymptote were not significantly different, while asymptotes differed significantly. Differences of scute ring- and Sexton-aged individuals from von Bertalanffy model estimates were not significant through age five for males and six for females. I estimated that 153, !57, and 235 individuals were found in the lake at densities of 5.1, 5.2, and 7.8 turtles/ha in 1994. 1995, and 1996, respectively. Associated biomass estimates were 3.84, 3.94, and 5.90 kg/ha, respectively. The overall sex ratio was female-biased, whereas the adult sex ratio was male-biased; both were not significantly different from equality. Key Words: Population ecology: Growth: Diet: Population structure; Tcstudines; Emydidae: Pseudemys concinna. Ecological studies can elucidate specific life its state-endangered status in Illinois (Herkert history traits which can be utilized in conservation 1992), and because of the scarcity of information and management planning. Many chelonian ecology concerning its natural history and ecology. -

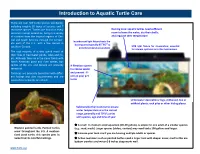

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Year of the Turtle News No

Year of the Turtle News No. 1 January 2011 Basking in the Wonder of Turtles www.YearoftheTurtle.org Welcome to 2011, the Wood Turtle, J.D. Kleopfer Bog Turtle, J.D. Willson Year of the Turtle! Turtle conservation groups in partnership with PARC have designated 2011 as the Year of the Turtle. The Chinese calendar declares 2011 as the Year of the Rabbit, and we are all familiar with the story of the “Tortoise and the Hare”. Today, there Raising Awareness for Turtle State of the Turtle Conservation is in fact a race in progress—a race to extinction, and turtles, unfortunately, Trouble for Turtles Our Natural Heritage of Turtles are emerging in the lead, ahead The fossil record shows us that While turtles (which include of birds, mammals, and even turtles, as we know them today, have tortoises) occur in fresh water, salt amphibians. The majority of turtle been on our planet since the Triassic water, and on land, their shells make threats are human-caused, which also Period, over 220 million years ago. them some of the most distinctive means that we can work together to Although they have persisted through animals on Earth. Turtles are so address turtle conservation issues many tumultuous periods of Earth’s unique that some scientists argue that and to help ensure the continued history, from glaciations to continental they should be in their own Class of survival of these important animals. shifts, they are now at the top of the vertebrates, Chelonia, separate from Throughout the year we will be raising list of species disappearing from the reptiles (such as lizards and snakes) awareness of the issues surrounding planet: 47.6% of turtle species are and other four-legged creatures. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

The Western Pond Turtle (Emys Marmorata) in the San Diego MSCP and Surrounding Areas Melanie Madden-Smith

The Western Pond Turtle (Emys marmorata) in the San Diego MSCP and Surrounding Areas Melanie Madden-Smith U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Purpose Determine the current distribution and population status of the western pond turtle in the San Diego MSCP and surrounding areas. Determine wetland and upland habitat value. Provide management recommendations for the San Diego MSCP. Background- Western Pond Turtle Decline in Southern California Only turtle native to coastal California. Historically occurred in most major coast facing drainages from northern Baja to Washington (Jennings and Hayes 1994). Work by Brattstrom and Messer (1988) suggested only a few populations of pond turtles remained in Southern California and those that did were comprised of few individuals. Background- Western Pond Turtle Decline in Southern California Principal cause of pond turtle decline is riparian habitat loss and alteration. Exotic turtles thought to out-compete for resources (food and basking spots), transmit diseases. Other introduced species, such as large mouth bass and crayfish. Habitat Decline or Destruction Study Area Types of Surveys Trapping Visual Checking Traps by Land Checking Traps by Boat Removing Pond Turtles (7) from Trap Pond Turtle Processing Shell measurements Weight Sex Deformities Injuries Assigned Unique ID Marking Rt Femoral Scute Front Carapace Plastron Other Animals Captured Exotic Turtle Species Captured Red-eared Slider Yellow-bellied Slider Unknown Slider Species Painted Turtle Mud Turtle Exotic Turtle Species Captured False Map Turtle Mississippi Map Turtle Spiny Softshell Snapping Turtle Results- Turtle Detections San Diego County: June - October 2002/2003 336 total (7 species; 10 subspecies) 263 exotics (6 species, 9 subspecies) 73 pond turtles Pond Turtle and Exotic Turtle Locations Pond Turtles Exotic Turtles Habitat Types and Human Access Habitat Types: Natural- ponds, wetlands, etc. -

Caring for Your River Cooter Turtles

caring for your River Cooter Turtles Scientific Name: Pseudemys concinna Native to: Central and Eastern United States Maximum Length: Females up to 16 inches, males up to 10 inches Life Span: 40 + years characteristics: River Cooters are large turtles with relatively flat shells. River Cooters have a brown to black carapace, with reddish tinges, and the plastron is yellow, orange or reddish with prominent patterns of orange and black. Their head stripes are yellow, but may even seem orange. These gorgeous turtles are good for a beginner. River Cooters are typically found in large rivers with clear water, gravel river beds, and aquatic plants. care tips: Enclosure: Juvenile River Cooters can be kept in a 20 – 30 gallon long tank, adults require much larger accommodations. A minimum 300 gallon tank is needed to house an adult River Cooter. Substrate: Reptile sand or even fine pea gravel. Habitat: Cooters do well in aquariums when the water is kept clean and filtered. Make sure to provide plenty of space for your River Cooter including a basking area where they can get completely out of the water and swimming area with water deep enough to swim. Temperature and Lighting: Provide UVB lighting, a basking area of 85 degrees and water temperature of 75 degrees are recommended for these turtles. The basking platform must allow River Cooters enough room to stretch out and fully dry their shell and plastron to avoid shell rot. Food and Water: River Cooters are omnivores. Their diet should consist of a mix of pelleted turtle food, crickets, mealworms, and leafy greens such as romaine, collard, and turnip greens.. -

Invasion of the Turtles? Wageningen Approach

Alterra is part of the international expertise organisation Wageningen UR (University & Research centre). Our mission is ‘To explore the potential of nature to improve the quality of life’. Within Wageningen UR, nine research institutes – both specialised and applied – have joined forces with Wageningen University and Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences to help answer the most important questions in the domain of healthy food and living environment. With approximately 40 locations (in the Netherlands, Brazil and China), 6,500 members of staff and 10,000 students, Wageningen UR is one of the leading organisations in its domain worldwide. The integral approach to problems and the cooperation between the exact sciences and the technological and social disciplines are at the heart of the Invasion of the turtles? Wageningen Approach. Alterra is the research institute for our green living environment. We offer a combination of practical and scientific Exotic turtles in the Netherlands: a risk assessment research in a multitude of disciplines related to the green world around us and the sustainable use of our living environment, such as flora and fauna, soil, water, the environment, geo-information and remote sensing, landscape and spatial planning, man and society. Alterra report 2186 ISSN 1566-7197 More information: www.alterra.wur.nl/uk R.J.F. Bugter, F.G.W.A. Ottburg, I. Roessink, H.A.H. Jansman, E.A. van der Grift and A.J. Griffioen Invasion of the turtles? Commissioned by the Invasive Alien Species Team of the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority Invasion of the turtles? Exotic turtles in the Netherlands: a risk assessment R.J.F. -

The Natural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2010 The aN tural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia Linh Diem Phu Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Phu, Linh Diem, "The aN tural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia" (2010). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 787. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia Thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences By Linh Diem Phu Dr. Thomas K. Pauley, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Dr. Dan Evans, Ph.D. Dr. Suzanne Strait, Ph.D. Marshall University May 2010 Abstract Turtles are unique evolutionary marvels that evolved from amphibians and developed their protective shelled form more than 200 million years ago. In West Virginia, there are 10 native species of turtles, 9 of which are aquatic. Most of these aquatic turtles feed on carrion and dead plant matter, in the water and essentially "clean" our water systems. Turtles are long-lived animals with sensitive life stages that can serve as both long-term and short-term bioindicators of environmental health. With the increase in commercial trade, habitat fragmentation, degradation, destruction, there has been a marked decline in turtle species. -

Turtles of the Upper Mississippi River System

TURTLES OF THE UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER SYSTEM Tom R. Johnson and Jeffrey T. Briggler Herpetologists Missouri Department of Conservation Jefferson City, MO March 27, 2012 Background: A total of 13 species and subspecies of turtles are known to live in the Upper Mississippi River, its backwaters and tributaries. There are a few species that could be found occasionally, but would likely account for less than 5% of the species composition of any area. These species are predominantly marsh animals and are discussed in a separate section of this paper. For additional information on turtle identification and natural history see Briggler and Johnson (2006), Christiansen and Bailey (1988), Conant and Collins (1998), Ernst and Lovich (2009), Johnson (2000), and Vogt (1981). This information is provided to the fisheries field staff of the LTRM project so they will be able to identify the turtles captured during fish monitoring. The most current taxonomic information of turtles was used to compile this material. The taxonomy followed in this publication is the Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with comments regarding confidence in our understanding (6th edition) by Crothers (2008). Species Identification, Natural History and Distribution: What follows is a synopsis of the 13 turtle species and subspecies which are known to occur in the Upper Mississippi River environs. Species composition changes between the upper and lower reaches of the LTRM study area (Wisconsin/Minnesota state line and southeastern Missouri) due to changes in aquatic habitats. For example, the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica) is abundant in the northern portion of the river with clearer water and abundant snail prey. -

North Louisiana Refuges Complex: Freshwater Turtle Inventory

NORTH LOUISIANA REFUGES COMPLEX: FRESHWATER TURTLE INVENTORY USFWS Award No: F17PX01556 John L. Carr, Aaron C. Johnson & J. Benjamin Grizzle November 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Inventory and Monitoring Branch for USFWS Award No. F17PX01556, “Freshwater Turtle Inventory of the North Louisiana Refuges Complex”. In addition, this report incorporates data from other, complementary projects that were funded by a variety of sources. This has been done in order to provide a more fulsome picture of knowledge on the turtle fauna of the refuges within the Complex. These other projects were funded in part by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Aid, through the State Wildlife Grants Program (series of projects targeting the Alligator Snapping Turtle and map turtles). Other sources include data collected for grant activities funded by USGS-BRD (Cooperative Agreement No. 99CRAG0017), funding from the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Foundation beginning in 1998, funding directly from LDWF (2000-2002), The Nature Conservancy (contract #LAFO_022309), Friends of Black Bayou, the Turtle Research Fund of the University of Louisiana at Monroe Foundation, and the Kitty DeGree Professorship in Biology (2011-2017). U.S. Fish and Wildlife personnel helped facilitate our work by granting access to all parts of the refuges at various times, and providing a series of Special Use Permits over 20+ years. We acknowledge Lee Fulton, Joe McGowan, Brett Hortman, Kelby Ouchley, and George Chandler for facilitating our work on refuges over the years; in particular, we thank Gypsy Hanks for long-sustained support and cooperation, especially during the course of the current project.