Countering Insecurity in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptions of the Impact of Informal Peace Education Training in Uganda

International School for Humanities and Social Sciences Prins Hendrikkade 189-B 1011 TD Amsterdam The Netherlands Masters Thesis for the MSc Programme International Development Studies Field Research carried out in Uganda 30th January - 27th May 2006 Teaching Peace – Transforming Conflict? Exploring Participants’ Perceptions of the Impact of Informal Peace Education Training in Uganda Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed. (Constitution of UNESCO, 1945) First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. G.C.A. Junne Second Supervisor: Dr. M. Novelli Anika May Student Number: 0430129 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 Chapter One: Introduction – Subject of Research 6 1.1 Purpose of the Study 8 1.2 Research Questions 9 1.3 Relevance of the Study 9 1.4 Structure of Thesis 12 Chapter Two: Background of the Research/Research Setting 14 2.1 Violence and Conflict in the History of Uganda 14 2.2 The Legacy of Violence in Ugandan Society 18 2.2.1 The Present State of Human Rights and Violence in Uganda 18 2.2.2 Contemporary Ugandan Conflicts 20 2.2.2.1 The Case of Acholiland 20 2.2.2.2 The Case of Karamoja 22 2.2.3 Beyond the Public Eye – The Issue of Gender-Based Domestic Violence in Uganda 23 Chapter Three: Theoretical Framework - Peace Education 25 3.1 The Ultimate Goal: a Peaceful Society 25 3.1.1 Defining Peace 26 3.1.2 Defining a Peaceful Society 27 3.2 Education for Peace: Using Education to Create a Peaceful Society 29 3.2.1 A Short History of Peace Education -

Education in Emergencies, Food Security and Livelihoods And

D e c e m b e r 2 0 1 5 Needs Assessment Report Education in Emergencies, Food Security, Livelihoods & Protection Fangak County, Jonglei State, South Sudan Finn Church Aid By Finn Church Aid South Sudan Country Program P.O. Box 432, Juba Nabari Area, Bilpham Road, Juba, South Sudan www.finnchurchaid.fi In conjunction with Ideal Capacity Development Consulting Limited P.O Box 54497-00200, Kenbanco House, Moi Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected], [email protected] www.idealcapacitydevelopment.org 30th November to 10th December 2015 i Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... VII 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 FOOD SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD, EDUCATION AND PROTECTION CONTEXT IN SOUTH SUDAN ............................... 1 1.2 ABOUT FIN CHURCH AID (FCA) ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT IN FANGAK COUNTY .................................................................................................. 2 1.4 PURPOSE, OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................... -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 December 7, 2018

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 DECEMBER 7, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Relief actor records at least 150 GBV cases in Bentiu during a 12-day period 5% 7% 20% UN records two aid worker deaths, 60 7 million 7% Estimated People in South humanitarian access incidents in October 10% Sudan Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP partner reaches 2.3 million Assistance 19% 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan – people with assistance in October December 2017 15% 17% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE 6.1 million Health (17%) Nutrition (15%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/FFP $402,253,743 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) September 2018 Shelter & Settlements (5%) 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $628,994,9784 2 million BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 Estimated IDPs in 84% 9% 5% South Sudan OCHA – November 8, 2018 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,760,121,951 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES 194,900 Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases KEY DEVELOPMENTS UNMISS – November 15, 2018 During a 12-day period in late November, non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recorded at least 150 gender-based violence (GBV) cases in Unity State’s Bentiu town, representing a significant increase from the approximately 2.2 million 100 GBV cases that MSF recorded in Bentiu between January and October. -

Knowledge Sovereignty Among African Cattle Herders

Knowledge Sovereignty ‘This ground-breaking ethnography of Beni-Amer pastoralists in the Horn of Africa shows how a partnership of conventional science and local indigenous knowledge can generate a hybrid knowledge system which underpins a productive cattle economy. This has implications for sustainable pastoral development around the world.’ Knowledge Jeremy Swift, Emeritus Fellow, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex ‘Indigenous knowledge and the sovereignty issues addressed in the book are hallmarks to Sovereignty recognize African cattle herders and also to use this knowledge to mitigate climate change and appreciate the resilience of these herders. The book will be a major resource for students, researchers among and policy makers in Africa and worldwide.’ Mitiku Haile, Professor of Soil Science and Sustainable Land Management, Mekelle University ‘This important book arrives at a key moment of climate and food security challenges. Fre deploys among African great wisdom in writing about the wisdom of traditional pastoralists, which – refl ecting the way complex natural systems really work – has been tested through history, and remains capable of future evolution. The more general lesson is that both land, and ideas, should be a common treasury.’ Cattle African Cattle Herders Cattle African Robert Biel, Senior Lecturer, the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, UCL Beni-Amer cattle owners in the western part of the Horn of Africa are not only masters in cattle Herders breeding, they are also knowledge sovereign, in terms of owning productive genes of cattle and the cognitive knowledge base crucial to sustainable development. The strong bonds between the Beni- Amer, their animals, and their environment constitute the basis of their ways of knowing, and much of their knowledge system is built on experience and embedded in their cultural practices. -

Interethnic Conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging Ethnic Hatred Between the Lou Nuer and the Murle

Interethnic conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging ethnic hatred between the Lou Nuer and the Murle Yuki Yoshida* Abstract This article analyses the escalation of interethnic confl icts between the Lou Nuer and the Murle in Jonglei State of South Sudan. Historically, interethnic confl icts in Jonglei were best described as environmental confl icts, in which multiple ethnic groups competed over scarce resources for cattle grazing. Cattle raiding was commonly committed. The global climate change exacerbated resource scarcity, which contributed to intensifying the confl icts and developing ethnic cleavage. The type of confl ict drastically shifted from resource-driven to identity-driven confl ict after the 2005 government-led civilian disarmament, which increased the existing security dilemma. In the recent confl icts, there have been clear demonstrations of ethnic hatred in both sides, and arguably the tactics used amounted to acts of genocide. The article ends with some implications drawn from the Jonglei case on post-confl ict reform of the security sector and management of multiple identities. * Yuki Yoshida is a graduate student studying peacebuilding and conflict resolution at the Center for Global Affairs, New York University. His research interests include UN peacekeeping, post-conflict peacebuilding, democratic governance, humanitarian intervention, and the responsibility to protect. He obtained his BA in Liberal Arts from Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, CA, in 2012. 39 Yuki Yoshida Introduction After decades of civil war, the Republic of South Sudan achieved independence in July 2011 and was recognised as the newest state by the international community. However, South Sudan has been plagued by the unresolved territorial dispute over the Abyei region with northern Sudan, to which the world has paid much attention. -

1 South Sudan 2016 Common

SOUTH SUDAN 2016 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND: FIRST ROUND STANDARD ALLOCATION RECOMMENDED PROJECTS FOR FUNDING TOTAL AMOUNT: USD 4,747,751.41 1 NAMES OF INGOs and NGOs FUNDED Organization Project title Duration Budget Location Beneficiaries CCM (Comitato Improve the 6 months $199,562.52 Lakes -> Awerial 69248 Collaborazione quality of Medica) essential health service delivery (safety nets) and strengthen the emergency response to the humanitarian needs, including obstetric services and supportive care to GBV victims in Mingkamann and underserved area of selected counties of Lakes. CMA (Christian Strengthening 6 months $199,999.91 Jonglei -> Fangak 96196 Mission Aid) the capacity of primary health care facilities to deliver life saving emergency health services integrated with nutrition services in Fangak county of Jonglei State 2 CUAMM Improving host 6 months $276,978.21 Western Equatoria - 45375 (Collegio and displaced > Mundri East Universitario population and Aspirante e other Medici vulnerable Missionari) groups’ access to and utilization of quality essential and emergency health services in Mundri East County (Western Equatoria State) GOAL (GOAL) Provision of 6 months $300,000.00 Warrap -> Twic; 64782 integrated and Upper Nile -> Melut; lifesaving Upper Nile -> Primary Health Maiwut; Upper Nile Care (PHC) -> Ulang; Warrap services for conflict affected and vulnerable populations and strengthening emergency responses in Baliet, Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties, Upper Nile State (UNS), Twic, Warrap State and Agok: Abyei Administrative -

South Sudan Arabica Coffee Land Race Survey in Boma Germplasm Assessment and Conservation Project Report Dr

South Sudan Arabica Coffee Land Race Survey in Boma Germplasm Assessment and Conservation Project Report Dr. Sarada Krishnan Dr. Aaron P. Davis 1. Introduction and Background: Coffee is an extremely important agricultural commodity (Vega et al. 2003) produced in about 80 tropical countries, with an annual production of nearly seven million tons of green beans (Musoli et al. 2009). It is the second most valuable commodity exported by developing countries after oil, with over 75 million people depending on it for their livelihood (Vega et al. 2003; Pendergrast 2009). It is thought that coffee was introduced to Yemen from its origins in Ethiopia around the sixth century (Pendergrast 1999). From Yemen, two genetic bases spread giving rise to most of the present commercial cultivars of Arabica coffee grown worldwide (Anthony et al. 2002). The two sub-populations of wild coffee introduced from Ethiopia to Yemen underwent successive reductions in genetic diversity with the first reduction occurring with the introduction of coffee to Yemen 1,500 to 300 years ago (Anthony et al. 2002). Introduction of coffee to Java, Amsterdam, and La Réunion at the beginning of the 18th century led to further reductions in genetic diversity (Anthony et al. 2002). In addition to Ethiopia, wild plants of C. arabica were observed in the Boma Plateau of South Sudan (Thomas 1942; Meyer 1965) and Mount Marsabit in northern Kenya (Meyer 1965). A consortium led by Texas A&M University’s Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture has been commissioned to support the John Garang University of Science and Technology (JG-MUST) of South Sudan. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute a Thesis Submitted in Parti

University of Nevada, Reno Persistence in Aurora, Nevada: Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Lauren Walkling Dr. Carolyn White/Thesis Advisor May 2018 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by LAUREN WALKLING Entitled Persistence in Aurora, Nevada: Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Carolyn L White, Ph.D., Advisor Sarah Cowie, Ph.D, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2018 i Abstract Negotiation and agency are crucial topics of discussion, especially in areas of colonial and cultural entanglement in relation to indigenous groups. Studies of agency explore the changes, or lack thereof, in material culture use and expression in response to colonial intrusion and cultural entanglement. Agency studies, based on dominance and resistance, use material and documentary evidence on varying scales of analysis, such as group and individual scales. Agency also discusses how social aspects including gender, race, and socioeconomic status affect decision making practices. One alternative framework to this dichotomy is that of persistence, a framework that focuses on how identity and cultural practices were modified or preserved as they were passed on (Panich 2013: 107; Silliman 2009: 212). Using the definition of persistence as discussed by Lee Panich (2013), archaeological evidence surveyed from a group of historic Paiute sites located outside of the mining town, Aurora, Nevada, and historical documentation will be used to track potential persistence tactics. -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

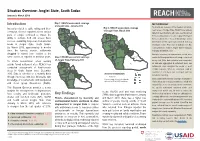

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

The Origin of the Maasai and Kindred African Tribes and of Bornean Tribes

ct (MEMO' 5(t(I1MET• fiAltOtOHHE4GfO HATHOl\-ASMTAi\f 0E\I1l: HALF MAti AtSO '''fJ1nFHH> \.,/i1'~ NUT. t1At~ Bl~t),WHO HEAD OF· PROPElS HIM:. ENtiAt 5ftFwITI'f ("ufCn MATr4OR, (OW ~F f1AA~AI PLATE: .0'\. PREFACE. The research with which this review deals having been entirely carried out here in Central Africa, far away from all centres of science, the writer is only too well aware that his work must shown signs of the inadequacy of the material for reference at his disposal. He has been obliged to rely entirely on such literature as he could get out from Home, and, in this respect, being obliged for the most psrt to base his selection on the scanty information supplied by publishers' catalogues, he has often had many disappointments when, after months of waiting, the books eventually arrived. That in consequence certain errors may have found their way into the following pages is quite posaible, but he ventures to believe that they are neither many nor of great importance to the subject as a whole. With regard to linguistic comparisons, these have been confined within restricted limits, and the writer has only been able to make comparison with Hebrew, though possibly Aramaic and other Semitic dialects might have carried him further. As there is no Hebrew type in this country he has not been able to give the Hebrew words in their original character as he should have wished. All the quotations from Capt. M. Merker in the following pages are translations of the writer; he is aware that it would have been more correct to have given them in the original German, but in this case they would have been of little value to the majority of the readers of this Journal in Kenya.