Four Quarters Volume 8 Article 1 Number 4 Four Quarters: May 1959 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bestand Neuware(34563).Xlsx

Best.‐Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0002 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0003 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0004 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0005 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0006 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0007 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0008 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0009 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0010 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0011 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0012 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0013 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0014 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0015 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0016 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0017 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0018 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0019 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0020 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0021 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0022 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0023 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € Dez. 20 0028 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. 20 0029 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. -

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis Release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit Weg Von Zu Hause 17,50 € Mai

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von zu Hause 17,50 € Mai. 21 0002 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0003 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0004 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0005 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0006 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0007 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0008 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0009 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0010 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0011 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0012 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0013 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0014 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0015 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0016 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0017 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0018 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0019 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0020 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0021 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0022 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0023 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0028 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0029 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. -

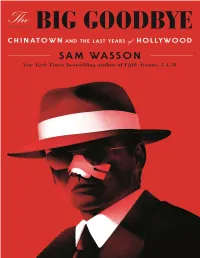

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

LOCAL CROSSWORD NATE UTESCH NOMADLAND PUZZLE FEATURES CLUES BASED on WHAT’S LOCAL GRAPHIC FRANCES Mcdormand STARS in CAPTIVATING Give It up for

February 18-24, 2021 THINGS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND FREE Your source for local music and entertainment SWEETWATER ALL STARS MUSICAL DREAM TEAM PLAYS SOUL, R&B AT THE CLUB ROOM · PAGE 3 LOCAL CROSSWORD NATE UTESCH NOMADLAND PUZZLE FEATURES CLUES BASED ON WHAT’S LOCAL GRAPHIC FRANCES MCDORMAND STARS IN CAPTIVATING Give it up for ... GOING ON IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND / PAGE 14 DESIGNER CREATES ALBUM COVERS FOR MOVIE ABOUT Across 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 NATIONAL BANDS, TRANSIENCE, TRAUMA 1. Technical drawer 13 14 8. Go with the flow LIKE SMASHING starstarstarstarStar-half-alt 15 16 13. Shine PUMPKINS / PAGE 4 REEL VIEWS, PAGE 15 14. More tender 17 18 19 15. Rare 20 21 22 23 16. Latin word for horn 24 25 26 17. Dissolve 27 28 29 30 31 32 18. A doctrine that 33 34 35 the physical and mental universe is 36 37 38 39 40 41 composed of simple 42 43 44 indivisible minute particles 45 46 47 48 20. Arrangement 49 50 22. Tit for ___ 23. Big shot 51 52 24. Place for a boutonniere 26. Map abbr. 44. ___ vera 5. Fraternity letter 32. Ancient fertility 27. * "Bob Bailey, 45. Ness of "The 6. Pilot's goddess Lisa McDavid, and Untouchables" announcement, 35. "The magic word" Don Carr on __" 46. Attribute briefly 37. Sedans, 30. Swiss cottage 49. Copy 7. Pertain Compacts, etc. 33. Portfolio part, in 8. Fancy tie 39. Roswell crash brief 50. Quick fried 9. -

130Db Metal Top 40-Vorige Week-SITE

Deze Vorige Aantal Hoogste Band Single Album YT views Release week week weken notering afgelopen Datum week Album 322 282 4 179 Hildr Valkyrie We Are Heathens Revealing The Heathen Sun 13 14-05-2021 321 283 3 218 Von Veh Openly Remember Openly Remember (Single) 27 21-02-2021 320 246 2 246 Dormanth Odyssey in Time Complete Downfall 44 15-12-2020 319 267 3 202 Heavy Sentence Cold Reins Bang to Rights 63 28-05-2021 318 261 2 261 Bunker 66 The Ride of the Goat Beyond the Help of Prayers 72 30-04-2021 317 280 3 211 Mindless Sinner We go Together Turn on the Power 73 30-04-2021 316 272 6 186 Heavy Sentence Age of Fire Bang to Rights 74 20-05-2021 315 281 7 183 Herzel L’épée des Dieux Le Dernier Rempart 74 19-03-2021 314 231 2 231 Lucifuge Black Light of the Evening Star Infernal Power 78 10-04-2021 313 156 2 156 Eisenhand Dead of Night Fires Within 100 28-05-2021 312 274 3 197 Ossaert De Geest en de Vervoering Pelgrimsoord 104 04-06-2021 311 277 6 181 Miasmata Unlight: Songs of Earth and Unlight: Songs of Earth and 106 14-03-2021 Atrophy Atrophy 310 264 2 264 Backwood Spirit Catch Your Fire Fresh From the Can 118 23-04-2021 309 273 3 165 Necrophagous Order of the Lion In Chaos Ascend 121 Soon 308 252 2 252 Insane At Dawn They Die Victims 130 30-04-2021 307 269 5 178 Nordsind For Evigt Forblændet Lys 134 26-03-2021 306 275 4 125 Abyssus The Beast Within Death Revival 169 Onbekend 305 270 4 171 Backwood Spirit Witchwood Fresh From the Can 170 23-04-2021 304 196 2 196 Ande De Messentrekker Bos 173 18-04-2021 303 271 3 195 Axewitch The Pusher Out -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

INSIDE: DAVID HILLIARD SPEAKS on B.S.U.'S the BLACK PANTHER

STITUCT CHIEDENIS 3AM Black Community News Service VOL. IV NO. 4 SATURDAY^ DECEMBER 27, 19694 MINISTRY OF INFORMATION PUBLISHED BOX 2967, CUSTOM HOUSE WEEKLY THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94126 "Although my body may be bound and shackled, the driving force cannot be held down by chains and will always pick freedom and dignity." LANDON WILLIAMS, B.P.P. POLITICAL PRISONER DENVER, COLORADO 0 4'**' "Only with the Death of fascist America can we be free." RORY HITHE, B.P.P. POLITICAL PRISOHER DENVER, COLORADO MO JUSTICE IM AMERIKKKA STATEMENT TO TNE P.R.G. of S.V. FROM ELDRIDGE CLEAVER INSIDE: DAVID HILLIARD SPEAKS ON B.S.U.'s THE BLACK PANTHER. SATURDAY. DECEMBER 27, 1969 PAGE 2 L. A. PIGS CONDEMN PEOPLES' OFFICE Press Release culated to bring about its physical ples generally have been subjected Southern California Chapter, destruction. to for 400 hundred years, a farce Black Panther Party In cohesion with the rest of the and a poor joke. December i9, 1969 various governmental agencies, the The brothers and sisters who defended the office on December 8, Los Angeles Department of Building As part ofthe national conspiracy and Public Safety has joined the ef who defended the liberated terri to wipe out the Black Panther Party, forts of eradicating the Black tory that belongs to the people, efforts are now being made to lit Panther Party ( at least in Los would be very disappointed if we erally put us out, evict us from the Angeles). And are forcing absentee, moved. And the Black Panther Party premises at 4115 South Central slumlord Morris Rosen to serve is here to serve notice along with Avenue, site of our Central Head- us notice to quit the premises. -

JIM SHOOTER! JIM GO BACK to the to BACK GO Comics�BY Legionnaires! Finding FATE of FATE 1960 1 S 8 2 6 5 8 2 7 7 6 3 in the USA the in $ 5 8.95 1 2

LEGiONNAiRES! GO BACK TO THE 1960s AND ALTER THE FATE OF No.137 COMiCSBY FiNDiNG January 2016 JIM SHOOTER! $8.95 In the USA 1 2 Characters TM & © DC Comics 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 137 / January 2016 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck If you’re viewing a Digital J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Edition of this publication, Comic Crypt Editor PLEASE READ THIS: Michael T. Gilbert This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our Editorial Honor Roll website or Apps. If you downloaded it from another website or torrent, go ahead and Jerry G. Bails (founder) read it, and if you decide to keep it, DO THE RIGHT THING and buy a legal down- Ronn Foss, Biljo White load, or a printed copy. Otherwise, DELETE Mike Friedrich IT FROM YOUR DEVICE and DO NOT SHARE IT WITH FRIENDS OR POST IT Proofreader ANYWHERE. If you enjoy our publications enough to download them, please pay for William J. Dowlding them so we can keep producing ones like this. Our digital editions should ONLY be Cover Artists downloaded within our Apps and at www.twomorrows.com Curt Swan & George Klein Cover Colorist Unknown With Special Thanks to: Paul Allen Paul Levitz Heidi Amash Mark Lewis Ger Apeldoorn Alan Light Contents Richard J. Arndt Doug Martin Bob Bailey Robert Menzies Writer/Editorial: “It Was 50 Years Ago Today…”. 2 Steven Barry Dusty Miller Alberto Becattini Will Murray “The Kid Who Wrote Comic Books” Speaks Out . -

Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note

Hard Rock / Heavy Metal www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 311 Down (1 track) 7870 1xCDs Capricorn EU CDPR001.311 USED 3,60 € PRO Mercury 311 Evolver 12533 1xCD Music for UK 5016583130329 USED 8,00 € nations 7 MONTHS 7 months 16423 1xCD Frontiers IT 8024391012123 5,90 € 700 MILES Dirtbomb 8951 1xCD RCA BMG USA 078636638829 USED 8,00 € 700 MILES 700 Miles 19281 1xCD RCA BMG USA 078636608129 USED 8,00 € A FOOT IN All around us 16234 1xCD Wounded bird USA WOU1025 10,90 € COLDWATER A PERFECT CIRCLE So long, and thanks for 22203 1x7" BMG Warner EU 4050538439427 NEW SS 13,90 € Black friday record all the fish \ Dog eat dog store day 2018 ABORTED Maniacult 33967 1xLP, 1xCD Century media GER 194398906010 NEW SS 30,00 € Deluxe edition 180g - Sony GF + poster AC/DC Back in black 4039 1xCD Epic Sony EU 5099751076520 13,90 € Remastered-Digipack AC/DC Stiff upper lip 5623 1xLP Albert EU 888430492813 NEW SS 22,00 € RE 180gm Columbia Sony AC/DC If you want 7605 1xCD Albert Epic EU 5099751076322 13,90 € Remastered-Digipack blood...you've got it Sony AC/DC Let there be rock 10281 1xDVD Warner EU 5051891025578 10,90 € Live Paris 09/12/1979 AC/DC Fly on the wall 10933 1xLP Atlantic Sony EU 5107681 NEW 23,00 € RE 180gm AC/DC For those about to rock 11128 1xCD Columbia EU 888750366627 13,90 € Remastered Sony AC/DC High voltage 12104 1xCD Epic Sony EU 5099751075929 13,90 € Remastered Digipack AC/DC Fly on the wall 12245 1xCD Albert Epic EU 5099751076827 12,90 € Remastered Digipack Sony Fri, 01 Oct 2021 21:00:37 +0000 Page 1 Hard Rock / Heavy Metal www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note AC/DC Dirty deeds done dirty 12425 1xCD Albert Epic EU 888750365927 13,90 € Remastered cheap Sony AC/DC Who made who 12548 1xLP Albert EU 5099751076919 NEW SS 22,00 € RE 180g - O.s.t. -

The Blue Guitar Magazine Staff Biographies

Table Of Contents “Garden Tattooed Roman” – Kip Sudduth ....................................46 Fiction “Chocolate Diva,” “Masquerade,” “Madd Skillz Poet,” “Trout Fishing in Alaska,” “Bubba Wingate” “Celebrate,” “Recognition of Haitian Heritage” – – J. Michael Green ...................................................................... 29-31 Cathy Delaleu ..........................................................................47-51 “Goodbye Marla”– Brittany Zelkovich ..................................... 41-43 “Bringing Out the Artist in Others” – Debra Lee Murrow ........73 “El Corrido de Panchiyo Gutierrez,” “The Junction” “Children of Bora Bora” – Mike Rothmiller .................................79 – Hugo Estrada Duran ................................................................ 63-72 News Non-Fiction Open Mic: A celebration of the arts .............................................74 “My Reunion With Truth” – Susan Bennett ............................ 11-12 All about The Arizona Consortium for the Arts ..........................74 “Arizona Winter Sunrise” – Michaele Lockhart ..................... 14-15 The Blue Guitar Spring Festival of the Arts ...............................75 “Last Gasp Love” – Kaitlin Meadows ...................................... 44-45 A thank-you to friends, contributors, supporters ........................80 “The Band Plays On” – Barclay Franklin ............................... 52-53 Sign up for consortium’s newsletter ..............................................81 The Blue Guitar magazine staff biographies -

Answer Me That

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2009 Answer Me That Catherine Davis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Catherine, "Answer Me That" (2009). Dissertations. 1074. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1074 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi ANSWER ME THAT by Catherine Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 COPYRIGHT BY CATHERINE DAVIS 2009 The University of Southern Mississippi ANSWER ME THAT by Catherine Davis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 ABSTRACT ANSWER ME THAT by Catherine Davis December 2009 This is a collection of five works of short fiction and one creative non-fiction essay. 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my dissertation director, Steven Barthelme, and my other committee members, Frederick Barthelme, Julia Johnson, Dr. Angela Ball, Dr. Kenneth Watson, and Dr. Charles Sumner for their advice and support regarding my work. I give special thanks to Steven Barthelme and Frederick Barthelme as my primary teachers and guides, for hundreds of hours of their workshop time, and for the compelling inspiration of their own work. -

God Did It: a History

GOD DID IT: A HISTORY The Words & Deeds of the Followers of Jesus Christ By: Peter Bormuth Copyright 2011 – all rights reserved “But a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit.” -Jesus of Nazareth Matthew (7: 17-18) 2000 BC – Luxor On the walls of the temple of Luxor are images of the conception, birth, and adoration of the divine child god Horus with Thoth announcing to the virgin (unmarried) Isis that she will conceive Horus with Kneph, the Holy Ghost impregnating the virgin, and with the infant being attended by three kings or magi bearing gifts. The Egyptians knew that the three wise men were the stars Mintaka, Anilam, and Alnitak in the belt of Orion but the star wisdom that is the basis of the story fails to be transferred into the Christian myth. Everything else is plagiarized. 780 BC – Dodona She was a priestess who came from Thebes to set up an oracle for the barbarian Greeks who did not remember their own history. In an oak forest she finds a clearing with a single oak tree that has an intermittent spring gushing forth at its feet. It also happens to be at a certain latitude. Here she founds the shrine of Zeus and trains three priestesses, called doves, who enter a trance and prophesize without remembering what they have said. 2 BC – Qumran While the Jesus myth is borrowed from the Egyptians the morality of Christianity comes from the Essenes.