The Big Goodbye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Kit Composite.Indd

August, 2005 Re: The Evolution of The Pilates Method: The Fletcher Work™ To Whom It May Concern, The Fletcher Work is the authentic evolution of the Pilates’ method. To be accurate and legitimate, any journalistic inquiry into contemporary Pilates must necessarily include this dynamic contribution. On behalf of The Ron Fletcher Company, I encourage you to take time to review the enclosed materials. Pilates is more than a contemporary fitness phenomenon. It is an extraordinarily effective conditioning method — nearly a century in development — whose time has finally come. Joseph Pilates’ original principles were absolutely sound, yet his wife, Clara, referred to her husband’s original work as “just the tip of the iceberg.” The development and evolution of the Pilates method over the last 35 years has been, in large part, the result of the work and vision of Ron Fletcher, their protégé and student for nearly three decades. Since Joseph PIlates’ death in 1968, no other individual has played a more pivotal role in the evolution and popularity of the Pilates method. Now in his eighties, Mr. Fletcher is one of only three such masters still teaching the Work. Should you have any questions regarding the enclosed information, or should you wish to pursue a related project, please do not hesitate to contact me. In addition to being one of the great luminaries of the Pilates world, Ron Fletcher is also very much alive, well and active… and he’s a great interview. Sincerely, Kyria Sabin encl The Ron Fletcher Company™ . POB 64971 . Tucson, AZ 85728-4971 . 520.323.7070 . -

DESTINATION: SPA VAC ATION Celebrate Spring—And Remove the Ravages of a Beastly Winter—With a Luxurious Hotel Spa Getaway

First Class DESTINATION: SPA VAC ATION Celebrate spring—and remove the ravages of a beastly winter—with a luxurious hotel spa getaway. Best Hotel Spa for a Spiritual Retreat: Four Seasons Resort Rancho Encantado It makes sense that you’d find a world-class spa in Santa Fe. perhaps more to the point, Santa Fe is a New Age-y kind For one thing, the glamour quotient is high—Ali MacGraw, of town, a place where people come to reinvent themselves Gene Hackman, Tommy Lee Jones, Shirley MacLaine, Alan and leave the stress of their previous lives far behind. With Arkin, Carol Burnett, Val Kilmer, and Ted Turner, the single its grand skies and infinite desert landscape, not to mention largest landowner in New Mexico, all have homes here, a rich history dating back to the arrival of the nomadic and stars like Robert Redford and Jane Fonda are frequent Paleo-Indians around 10,000 B.C., America’s second oldest visitors. (In fact, while we were there, we bumped into the city, founded in 1610, provides the perfect spiritual backdrop cowboy boot-wearing Fonda at Todos Santos, a magical little for a spa vacation. Nestled on 57 acres in Sangre de Cristo chocolate shop in the courtyard at historic Sena Plaza.) But Foothills, just 10 minutes from downtown Santa Fe, the Four APRIL 2014 | SHERIDAN ROAD 95 Rancho Encantado’s outdoor fireplace is the perfect spot to take in the beauty of a Southwestern sunset. Seasons Resort Rancho Encantado offers 65 self-contained ballooning, archeological tours to a variety of cultural events. -

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing?

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing? By Chairman of the U.S. based Romanian National Vanguard©2007 www.ronatvan.com v. 1.6 1 INDEX 1. Are Jews satanic? 1.1 What The Talmud Rules About Christians 1.2 Foes Destroyed During the Purim Feast 1.3 The Shocking "Kol Nidre" Oath 1.4 The Bar Mitzvah - A Pledge to The Jewish Race 1.5 Jewish Genocide over Armenian People 1.6 The Satanic Bible 1.7 Other Examples 2. Are Jews the “Chosen People” or the real “Israel”? 2.1 Who are the “Chosen People”? 2.2 God & Jesus quotes about race mixing and globalization 3. Are they “eternally persecuted people”? 3.1 Crypto-Judaism 4. Is Judeo-Christianity a healthy “alliance”? 4.1 The “Jesus was a Jew” Hoax 4.2 The "Judeo - Christian" Hoax 4.3 Judaism's Secret Book - The Talmud 5. Are Christian sects Jewish creations? Are they affecting Christianity? 5.1 Biblical Quotes about the sects , the Jews and about the results of them working together. 6. “Anti-Semitism” shield & weapon is making Jews, Gods! 7. Is the “Holocaust” a dirty Jewish LIE? 7.1 The Famous 66 Questions & Answers about the Holocaust 8. Jews control “Anti-Hate”, “Human Rights” & Degraded organizations??? 8.1 Just a small part of the full list: CULTURAL/ETHNIC 8.2 "HATE", GENOCIDE, ETC. 8.3 POLITICS 8.4 WOMEN/FAMILY/SEX/GENDER ISSUES 8.5 LAW, RIGHTS GROUPS 8.6 UNIONS, OCCUPATION ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMIA, ETC. 2 8.7 IMMIGRATION 9. Money Collecting, Israel Aids, Kosher Tax and other Money Related Methods 9.1 Forced payment 9.2 Israel “Aids” 9.3 Kosher Taxes 9.4 Other ways for Jews to make money 10. -

HAWK KOCH Producer

HAWK KOCH Producer Selected Credits: SOURCE CODE (Executive Producer) - Summit Entertainment - Duncan Jones, director UNTRACEABLE (Executive Producer) - Screen Gems/Lakeshore - Greg Hoblit, director FRACTURE (Executive Producer) - New Line - Greg Hoblit, director BLOOD AND CHOCOLATE (Producer) - MGM/Lakeshore - Katja von Garnier, director HOSTAGE (Executive Producer) - Miramax - Florent Emelio Siri, director THE RIVERMAN (Executive Producer) - Fox TV / A & E - Bill Eagles, director COLLATERAL DAMAGE (Executive Producer) - Warner Bros. - Andrew Davis, director FREQUENCY (Producer) - New Line - Greg Hoblit, director KEEPING THE FAITH (Producer) - Spyglass - Ed Norton, director THE BEAUTICIAN AND THE BEAST (Producer) - Paramount - Ken Kwapis, director PRIMAL FEAR (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Greg Hoblit, director VIRTUOSITY (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Brett Leonard, director LOSING ISAIAH (Producer) - Paramount - Stephen Gyllenhaal, director WAYNE’S WORLD 2 (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Stephen Surjik, director SLIVER (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Phillip Noyce, director WAYNE’S WORLD (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Penelope Spheeris, director NECESSARY ROUGHNESS (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Stan Dragoti THE LONG WALK HOME (Producer) - Miramax - Richard Pearce, director ROOFTOPS (Producer) - New Visions - Robert Wise, director THE POPE OF GREENWICH VILLAGE (Producer) - United Artists - Stuart Rosenberg, director THE KEEP (Producer) - Paramount - Michael Mann, director GORKY PARK (Producer) - Orion - Michael Apted, director A NIGHT IN HEAVEN (Producer) - Fox - John G. Avildsen, director HOKY TONK FREEWAY (Producer) - Universal - John Schlesinger, director THE IDOLMAKER (Producer) - United Artists - Taylor Hackford, director THE FRISCO KID (Executive Producer) - Warner Bros. - Robert Aldrich, director HEAVEN CAN WAIT (Executive Producer) - Paramount - Warren Beatty/Buck Henry, directors THE DROWNING POOL (Associate Producer) - Warner Bros. - Stuart Rosenberg, director . -

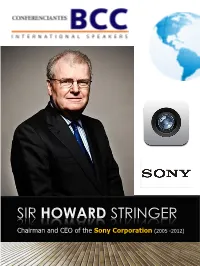

Sir Howard Stringer

SIR HOWARD STRINGER Chairman and CEO of the Sony Corporation (2005 -2012) Sir Howard served as Chairman and CEO of the Sony Corporation from June 2005 until June 2012 when he became Chairman of the Board of Directors, retiring in June 2013. Sir Howard joined Sony in May 1997 and was named Chairman and CEO of the Sony Corporation of America in 1998, responsible for Sony’s entertainment companies, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Sony Music Entertainment, and Sony Music Publishing. Prior to joining Sony, Sir Howard was President of CBS from 1988 to 1995, which became the first network to rise from last to first place in one season. From 1986 to 1988, Sir Howard served as President of CBS News. He was executive producer of the CBS Evening News with Dan Rather from 1981 to 1984, the dominant network evening newscast of its day. From 1976 to 1981, while he was executive producer of the CBS REPORTS, the documentary unit won more than 30 Emmys including nine individual awards. He holds a B.A. and an M.A. in Modern History from Oxford University. He also serves on the Board of Directors for TalkTalk and Time Inc., he is Chair of the School Board at Said Business School, Oxford University, Chair of the Board of Trustees for the American Film Institute and Chairman of Board of Advisors, Department of Opthalmology, Columbia University Medical Centre. Sir Howard has also received Honorary Doctorates from Oxford University, the University of Glamorgan, the University of the Arts London, the American Film Institute and the University of Swansea. -

(XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 22, 2019 (XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Mel Brooks WRITING Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg, Richard Pryor, and Alan Uger contributed to writing the screenplay from a story by Andrew Bergman, who also contributed to the screenplay. PRODUCER Michael Hertzberg MUSIC John Morris CINEMATOGRAPHY Joseph F. Biroc EDITING Danford B. Greene and John C. Howard The film was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Madeline Kahn, Best Film Editing for John C. Howard and Danford B. Greene, and for Best Music, Original Song, for John Morris and Mel Brooks, for the song "Blazing Saddles." In 2006, the National Film Preservation Board, USA, selected it for the National Film Registry. CAST Cleavon Little...Bart Gene Wilder...Jim Slim Pickens...Taggart Harvey Korman...Hedley Lamarr Madeline Kahn...Lili Von Shtupp Mel Brooks...Governor Lepetomane / Indian Chief Burton Gilliam...Lyle Alex Karras...Mongo David Huddleston...Olson Johnson Liam Dunn...Rev. Johnson Shows. With Buck Henry, he wrote the hit television comedy John Hillerman...Howard Johnson series Get Smart, which ran from 1965 to 1970. Brooks became George Furth...Van Johnson one of the most successful film directors of the 1970s, with Jack Starrett...Gabby Johnson (as Claude Ennis Starrett Jr.) many of his films being among the top 10 moneymakers of the Carol Arthur...Harriett Johnson year they were released. -

PAUL HIRSCH, ACE Editor

PAUL HIRSCH, ACE Editor PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS NUTCRACKER AND THE FOUR REALMS Lasse Hallstrom DISNEY / Mark Gordon Add’l Editor THE MUMMY 4 Alex Kurtzman UNIVERSAL / Sarah Bradshaw Alex Kurtzman Roberto Orci WARCRAFT Duncan Jones LEGENDARY / UNIVERSAL PICTURES Stuart Fenegan, Chuck Roven, Jon Jashni THE GREAT GATSBY Add’l Editor Baz Luhrmann RED WAGON / WARNER BROS. Marc Solomon LIFE OF PI Add’l Editor Ang Lee 20TH CENTURY FOX / Ted Gagliano MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE – GHOST Brad Bird BAD ROBOT / PARAMOUNT PROTOCOL J.J. Abrams, Jeffrey Chernov Winner, Best Editing – Saturn Awards SOURCE CODE Duncan Jones SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT Hawk Koch, Mark Gordon DEAD OF NIGHT Kevin Munroe Gil Adler, Ashok Amritraj LOVE RANCH Taylor Hackford DIBELLA ENTERTAINMENT Marty Katz RIGHTEOUS KILL Jon Avnet EMMETT/FURLA FILMS OVERTURE FILMS / Rob Cowan RAY Taylor Hackford UNIVERSAL PICTURES Nomination, Best Editing - Academy Awards Barbara Hall, Howard Baldwin Winner, Best Editing – A.C.E. Eddie Awards MISSION TO MARS Brian De Palma DISNEY / Sam Mercer, Tom Jacobson MIGHTY JOE YOUNG Ron Underwood RKO PICTURES / Michael Fottrell Ralph Winter, Tom Jacobson MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE Brian De Palma PARAMOUNT PICTURES Paula Wagner FALLING DOWN Joel WARNER BROS. Schumacher Bill Beasley, Dan Kolsrud STEEL MAGNOLIAS Herbert Ross TRISTAR / Ray Stark, Victoria White PLANES, TRAINS & AUTOMOBILES John Hughes PARAMOUNT / John Hughes Michael Chinich, Neil Machlis FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF John Hughes PARAMOUNT / Tom Jacobson FOOTLOOSE Herbert Ross PARAMOUNT / Daniel Melnick Lewis Rachmil, Craig Zadan BLOW OUT Brian De Palma CINEMA 77 / Fred Caruso, George Litto STAR WARS V: Irvin Kershner 20TH CENTURY FOX THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK Gary Kurtz, George Lucas THE FURY Brian De Palma 20TH CENTURY FOX Ron Preissman, Frank Yablans STAR WARS IV: A NEW HOPE George Lucas 20TH CENTURY FOX Winner, Best Editing - Academy Awards Gary Kurtz Nomination, Best Editing – BAFTA Awards Nomination, Best Editing – A.C.E. -

Love Letters at the Wallis Directed by Gregory Mosher 16 Performances Only! Oct 13 to 25, 2015

NEWS RELEASE Legendary Hollywood Stars ALI MACGRAW & RYAN O’NEAL Star in A.R. Gurney’s Love Letters At The Wallis Directed by Gregory Mosher 16 performances only! Oct 13 to 25, 2015 Beverly Hills, CA – (Sep 11, 2015) – They made history 45 years ago when they starred in Love Story, the most talked about film of its day--Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal now reunite for Love Letters, a special theatrical tour that will make its official tour launch at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Love Letters by celebrated American playwright A.R. Gurney is an enduring romance about first loves and second chances. It will perform Tuesay, Oct 13 through Sunday, Oct 25, (press opening Oct. 14), onstage at the Bram Goldsmith Theater at The Wallis. Love Letters is directed by two time Tony-winning director Gregory Mosher. Critical praise for Love Letters began in July during the U.S. tour’s preview Florida engagement. “The forever-linked co-stars of the 1970 movie Love Story are delivering something more than Gurney’s 1988 play: long-ago cinematic love and loss, nostalgia, the easy warmth of long-time friends,” said the Miami Herald. “In between, O’Neal and MacGraw bring Gurney’s rich characters to life in heartbreak and tears (and with lots of audible gasps from the audience). Certain truths about the heart don’t change. And neither do the chemistry and charisma of the Love Story/Love Letters stars.” About Love Letters Love Letters is the story of Andrew Makepeace Ladd III (O’Neal) and Melissa Gardner (MacGraw), two young people from similar backgrounds who take very different paths in life. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS Exclusive Auction Event of the Legendary Film Producer and Paramount Studio Executive of Hollywood’s Landmark Films, Chinatown, The Godfather, The Godfather II, Love Story, Rosemary’s Baby, Serpico, True Grit and More Robert Evans’ Fine Art Collection including Works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Helmut Newton, 1995 Jaguar XJS 2+2 Convertible, Furniture from his Beverly Hills Mansion, Film Scripts, Golden Globe Award, Rolodex, and More Offered for the First Time at Auction SATURDAY, OCTOBER 24TH, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (September 8th, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS, a celebration of the dazzling life and singular career of the legendary American film producer and studio executive, Robert Evans, who produced some of American cinema’s finest achievements and championed a new generation of commercial and artistic filmmaking from the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet, Roman Polanski, John Schlesinger and more in Hollywood. This exclusive auction event will take place Saturday, October 24th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2020 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS PRESS RELEASE Evans’ Jaguar convertible On offer is a spectacular collection of the Hollywood titan’s fine/decorative art, classic car, household items, film scripts, memorabilia and awards from Evans’ most iconic film productions, Chinatown, The Godfather, The Godfather II, Love Story, Rosemary’s Baby, Serpico, True Grit, and more.