Answer Me That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iceberg and Its Minimalist Implications in Raymond Carver's Fiction

Sinking the Titanic: The Iceberg and its Minimalist Implications In Raymond Carver's Fiction Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Spring 2006 By John Mozley Thesis Reader Deborah James Thesis Advisor Cynn Chadwick Mozley 1 When Raymond Carver died in 1988 of lung cancer, Robert Gotlieb, the then editor of The New Yorker, stated, "America just lost the writer it could least afford to lose" (Max 36). In Carver's mere twenty-year publishing career, he garnered such titles as "the American Chekhov" (London Times), "the most imitated American writer since Hemingway" (Nesset 2), and "as successful as a short story writer in America can be" (Meyer 239). Carver's stories won the O. Henry Award three consecutive years, he was nominated for the National Book Award in 1977 for Will You Please Be Quiet Please?. won two NBA awards for fiction, received a Guggenheim Fellowship as well as the "Mildred and Harold Strauss Living Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters" (Saltzman 3), and his collection of stories, Cathedral was nominated for both National Book Critics Circle award and a Pulitzer Prize (Saltzman 3). Born in Oregon in 1938, Carver grew up in Yakima, Washington where his father worked in the sawmill. At twenty years old, Carver was married to his high school sweetheart, Maryanne, and had two children (Saltzman 1). Plagued by debt and escalating alcoholism, the Carvers moved to California where Raymond "worked a series of low-paying jobs, including deliveryman, gas station attendant and hospital janitor, while his wife waited tables and sold door to door" (1), his jobs also included "sawmill worker. -

Table of Contents

Mechanized Advent Calendar (FDR) December 12, 2019 Team Naughty and Nice By Oma Skyrus [email protected] Tyler Koski [email protected] Danny Clifton [email protected] Sigrid Derickson [email protected] Sponsor Professor Lee McFarland Mechanical Engineering Department College of Engineering California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Cambria Christmas Market History...................................................................................... 1 2.2 Research ......................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2.1 Patents ................................................................................................................................................................................................2 2.2.2 Related Products............................................................................................................................................................................3 2.2.3 Journal Articles ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Bestand Neuware(34563).Xlsx

Best.‐Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0002 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0003 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0004 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0005 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0006 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0007 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0008 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0009 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0010 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0011 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0012 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0013 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0014 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0015 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0016 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0017 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0018 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 CD Box 0019 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0020 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0021 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0022 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0023 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € Dez. 20 0028 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. 20 0029 AC/DC Highway to hell 20,00 € Dez. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis Release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit Weg Von Zu Hause 17,50 € Mai

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von zu Hause 17,50 € Mai. 21 0002 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0003 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0004 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0005 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0006 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0007 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0008 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0009 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0010 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0011 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0012 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0013 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0014 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0015 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0016 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0017 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0018 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0019 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0020 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0021 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0022 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0023 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0028 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0029 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. -

74 Three Phases of Literary Minimalism

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialresearchjournals.com Volume 2; Issue 12; December 2016; Page No. 74-76 Three phases of literary minimalism Shazia Khatoon Department of English and Modern European Languages, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract Literary Minimalism elaborates new method of writing a text that advocates ordinary stuff, simple writing, and common life. It is away from all complex writing of the past that is based on action rather than reflection. It uses a method which eliminates nonessential details of a text and creates a new way of writing identify as Neo-realist, K-mart realism, and Dirty realism. Such writings are characterized by visual quality hence, focuses on visualising the story. This paper discusses the development of three phases of Literary Minimalism. Keywords: minimalism, realism, ordinary stuff, and common man etc. Introduction strong point to a story” (Darzikola 1) [11]. According to him an Minimalism emerges as a movement between 1960s-80s amateurish writer damages a story by omitting vital though it is influenced by the postmodern writing like neo- information without any mark. Whereas, if there is skilled realism, metafiction, and by several other art forms such as writer practices omission, it will strengthen a story as they Painting, Architecture, Music but basically it makes its ground invite readers to apply their own ideas. Moreover, writer also through the writings of Earnest Hemingway. Minimalism provides life experiences and moral values to the work, divides into three phases as first phase of literary Minimalism potentially resulting in deeper and more meaning of the text. -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip. -

Infomail 1456: Dvds Von PAUL Mccartney

Alter Markt 12 • 06 108 Halle (Saale) • Telefon 03 45 - 290 390 0 : Di., Mi., Do., Fr., Sa., So. und an Feiertagen jeweils von 10 bis 20 Uhr InfoMail 1456: DVDs von PAUL McCARTNEY Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan, wir haben folgende DVDs mit PAUL McCARTNEY: 3er DVD THE McCARTNEY YEARS. DVD 1: 1. Tug Of War; 2. Say Say Say; 3. Silly Love Songs; 4. Band On The Run; 5. Maybe I'm Amazed; 6. Heart Of The Country; 7. Mamunia; 8. With A Little Luck; 9. Goodnight Tonight; 10. Waterfalls; 11. My Love; 12. C Moon; 13. Baby's Request; 14. Hi Hi Hi; 15. Ebony And Ivory; 16. Take It Away; 17. Mull Of Kintyre; 18. Helen Wheels; 19. I've Had Enough; 20. Coming Up; 21. Wonderful Christmastime. Extra 1: Juniors Farm. Extra 2: Band On The Run. Extra 3: London Town. Extra 4: Oktober 1977: aus Fernsehsendung THE SOUTH BANK SHOW, Großbritannien: Mull Of Kintyre #2. DVD 2: 1. Pipes Of Peace; 2. My Brave Face; 3. Beautiful Night; 4. Fine Line; 5. No More Lonely Nights; 6. This One; 7. Little Willow; 8. Pretty Little Head; 9. Birthday; 10. Hope Of Deliverance; 11. Once Upon A Long Ago; 12. All My Trials; 13. Brown-Eyed Handsome Man; 14. Press; 15. No Other Baby; 16. Off The Ground; 17. Biker Like An Icon; 18. Spies Like Us; 19. Put It There; 20. Figure Of Eight; 21. C'Mon People. Extras: 1. PARKINSON; 2. So Bad. Extra 3: Donnerstag, 28. Juni 2005: CHAOS AND CREATION AT ABBEY ROAD. -

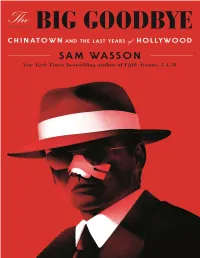

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

PAUL Mccartney: Alben Mccartney Und Mccartney II

Montag, 23. Mai 2011: PAUL McCARTNEY: Alben McCARTNEY und McCARTNEY II Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan, nun doch!!! Zunächst war geplant, die Alben McCARTNEY und McCARTNEY II als einzelne CDs nur in den USA zu veröffentlichen. Nun erscheinen sie - laut Universal Germany - auch in Europa. Nachstehend zwecks Übersicht alle Produkte der beiden Projekte McCARTNEY und McCARTNEY II, nun auch mit den Preisen. Freitag, 10. Juni 2011 (Europa) / Dienstag, 14. Juni 2011 (USA): CD McCARTNEY. 0888072321441, Universal, Deutschland. 12,90 € Track 1: The Lovely Linda. Track 2: That Would Be Something. Track 3: Valentine Day. Track 4: Every Night. Track 5: Hot As Sun / Glasses. Track 6: Junk. Track 7: Man We Was Lonely. Track 8: Oo You. Track 9: Momma Miss America. Track 10: Teddy Boy. Track 11: Singalong Junk. Track 12: Maybe I’m Amazed. Track 13: Kreen-Akrore. Doppel-CD McCARTNEY. 0888072327979, Universal, Deutschland. 22,90 € CD 1: Track 1: The Lovely Linda. Track 2: That Would Be Something. Track 3: Valentine Day. Track 4: Every Night. Track 5: Hot As Sun - Glasses. Track 6: Junk. Track 7: Man We Was Lonely. Track 8: Oo You. Track 9: Momma Miss America. Track 10: Teddy Boy. Track 11: Singalong Junk. Track 12: Maybe I'm Amazed. Track 13: Kreen - Akrore. CD 2: Track 14: Suicide (outtake). Track 15: Maybe I'm Amazed (from Film ONE HAND CLAPPING). Track 16 - 18: Sonntag, 16. Dezember 1979 oder (wahrscheinlicher) Montag, 17. Dezember 1979: Apollo, Glasgow; Schottland: Every Night (live); Hot As Sun (live); Maybe I'm Amazed (live). Track 19: Don't Cry Baby (outtake). -

DOHERTY-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf (733.0Kb)

State-Funded Fictions: The NEA and the Making of American Literature After 1965 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Doherty, Margaret. 2015. State-Funded Fictions: The NEA and the Making of American Literature After 1965. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467197 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA State-Funded Fictions: The NEA and the Making of American Literature After 1965 A dissertation presented by Margaret O’Connor Doherty to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, MA May 2015 © 2015 Margaret O’Connor Doherty All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Professor Louis Menand Margaret O’Connor Doherty State-Funded Fictions: The NEA and the Making of American Literature After 1965 Abstract This dissertation studies the effects of a patronage institution, the National Endowment for the Arts Literature Program, on American literary production in the postwar era. Though American writers had long cultivated informal relationships with government patrons, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) reflected a new investment in the aesthetic life of the nation. By awarding grants to citizens without independent resources for work yet to be produced, it changed both the demographics of authorship and the idea of the “professional” writer. -

LOCAL CROSSWORD NATE UTESCH NOMADLAND PUZZLE FEATURES CLUES BASED on WHAT’S LOCAL GRAPHIC FRANCES Mcdormand STARS in CAPTIVATING Give It up for

February 18-24, 2021 THINGS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND FREE Your source for local music and entertainment SWEETWATER ALL STARS MUSICAL DREAM TEAM PLAYS SOUL, R&B AT THE CLUB ROOM · PAGE 3 LOCAL CROSSWORD NATE UTESCH NOMADLAND PUZZLE FEATURES CLUES BASED ON WHAT’S LOCAL GRAPHIC FRANCES MCDORMAND STARS IN CAPTIVATING Give it up for ... GOING ON IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND / PAGE 14 DESIGNER CREATES ALBUM COVERS FOR MOVIE ABOUT Across 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 NATIONAL BANDS, TRANSIENCE, TRAUMA 1. Technical drawer 13 14 8. Go with the flow LIKE SMASHING starstarstarstarStar-half-alt 15 16 13. Shine PUMPKINS / PAGE 4 REEL VIEWS, PAGE 15 14. More tender 17 18 19 15. Rare 20 21 22 23 16. Latin word for horn 24 25 26 17. Dissolve 27 28 29 30 31 32 18. A doctrine that 33 34 35 the physical and mental universe is 36 37 38 39 40 41 composed of simple 42 43 44 indivisible minute particles 45 46 47 48 20. Arrangement 49 50 22. Tit for ___ 23. Big shot 51 52 24. Place for a boutonniere 26. Map abbr. 44. ___ vera 5. Fraternity letter 32. Ancient fertility 27. * "Bob Bailey, 45. Ness of "The 6. Pilot's goddess Lisa McDavid, and Untouchables" announcement, 35. "The magic word" Don Carr on __" 46. Attribute briefly 37. Sedans, 30. Swiss cottage 49. Copy 7. Pertain Compacts, etc. 33. Portfolio part, in 8. Fancy tie 39. Roswell crash brief 50. Quick fried 9.