FIGHTING AGAINST INDIGENOUS STEREOTYPES and INVISIBILITY: GREGG DEAL's USE of HUMOR and IRONY by Emily Mullen B.A., Regis Univ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

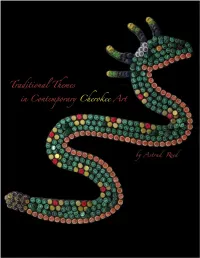

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

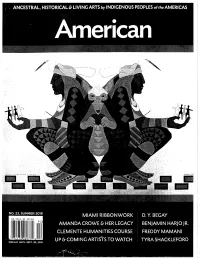

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By DENISE NEIL-BINION Norman, Oklahoma 2017 REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. Mary Jo Watson, Chair ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing III ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Swan © Copyright by DENISE NEIL-BINION 2017 All Rights Reserved. For the many people who instilled in me a thirst for knowledge. Acknowledgements I wish to extend my sincerest appreciation to my dissertation committee; I am grateful for the guidance, support, and mentorship that you have provided me throughout this process. Dr. Mary Jo Watson, thanks for being a mentor and a friend. I also must thank Thomas Lera, National Postal Museum (retired) and RoseMaria Estevez of the National Museum of the American Indian. The bulk of my inspiration and research developed from working with them on the Indians at the Post Office online exhibition. I am also grateful to the Smithsonian Office of Fellowships and Internships for their financial support of this endeavor. To my friends and colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, your friendship and support are truly appreciated. Tammi Hanawalt, heather ahtone, and America Meredith thank you for your encouragement, advice, and most of all your friendship. To the 99s Museum of Women Pilots, thanks for allowing me so much flexibility while I balanced work, school, and life. -

2021 Symposium on the American Indian Program

www.nsuok.edu/symposium · 48TH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM ON THE AMERICAN INDIAN · The 48th Annual Symposium on the American Indian will be held on April 13-17, 2020, centered on the theme, “Visionaries of Indian Country”. American Indians carry with them the knowledge, traditions, and language of their ancestors as they serve as leaders within their family, Tribe, and community. These visionaries are not just focused on the here and now, but are cognizant of how decisions made today will impact future genera- tions. This concept of the 7th generation is a way of life for many Indigenous people, a method of integrating the past, present and future. The visionaries of Indian Country are vital to the preservation and sustainability of our languages, community, environment and sovereignty. CONTENTS Agenda Overview................... 4 Symposium Film Series.......... 5 Symposium Sessions........ 6-11 SAVE THE DATE! NSU Powwow....................... 11 49th Annual Symposium on the American Indian: Keynote Speakers...........12-13 Fulfilling our Ancestors Dreams April 4-9, 2022 Breaking the Silence: .......... 14 #MMIWG #MeToo Art Show Sponsors..........................15-23 2 48th Annual Symposium on the American Indian | Visionaries of Indian Country DR. STEVE TURNER, President DR. DEBBIE LANDRY, Vice-President For Academic Affairs SARA BARNETT, Director, Center For Tribal Studies ABOUT THE SYMPOSIUM In 1972, a program of distinguished Native American lecturers was presented on the Northeastern State Univer- sity campus, laying the foundation for what has become the Annual Symposium on the American Indian. The symposium, nationally known in the Native American academic community, attracts visitors from across the United States and includes a growing number of international visitors each year. -

Inspirational Leadership Curriculum for Grades 8-12

The National Native American Hall of Fame recognizes and honors the inspirational achievements of Native Americans in contemporary history For Teachers This Native American biography-based curriculum is designed for use by teachers of grade levels 8-12 throughout the nation, as it meets national content standards in the areas of literacy, social studies, health, science, and art. The lessons in this curriculum are meant to introduce students to noteworthy individuals who have been inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame. Students are meant to become inspired to learn more about the National Native American Hall of Fame and the remarkable lives and contributions of its inductees. Shane Doyle, EdD From the CEO We, at the National Native American Hall of Fame are excited and proud to present our “Inspirational Leadership” education curriculum. Developing educational lesson plans about each of our Hall of Fame inductees is one of our organization’s key objectives. We feel that in order to make Native Americans more visible, we need to start in our schools. Each of the lesson plans provide educators with great information and resources, while offering inspiration and role models to students. We are very grateful to our supporters who have funded the work that has made this curriculum possible. These funders include: Northwest Area Foundation First Interstate Bank Foundation NoVo Foundation Dennis and Phyllis Washington Foundation Foundation for Community Vitality O.P. and W.E. Edwards Foundation Tides Foundation Humanities Montana National Endowment for the Humanities Chi Miigwech! James Parker Shield Watch our 11-minute introduction to the National Native American Hall of Fame “Inspirational Leadership Curriculum” featuring Shane Doyle and James Parker Shield at https://vimeo.com/474797515 The interview is also accessible by scanning the Quick Response (QR) code with a smartphone or QR Reader. -

Bacone College's

EVOLVING STATES Michael Elizondo Jr. and the Reemergence of the Bacone College School of Indian Art By Cedar Marie (Standing Rock Lakota descent) ACONE COLLEGE’S Peoria) depicted images and stories of the INFLUENCE on Michael Native American Church, a regular and Elizondo Jr. has evolved over important influence for Elizondo’s family. Btime. The oldest continuing As a young man and art student, Elizondo American Indian college in what is looked to these artists for inspiration. now Oklahoma, Bacone College was He wanted to express himself in his own chartered in 1880 and its campus was way while also keeping his culture as the later established in Muskogee within central subject matter in his artwork. the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Unlike Even though he did not attend Bacone’s many schools for Native students of its art school, when Elizondo researched time, Bacone College supported expres- artists and artworks that he could relate to sions of Native identity, cultures, and and learn from, his research nearly always visual arts. Its storied School of Art was led him back to Bacone College and the directed by Native artists and gave birth art department’s history of prominent to the Bacone school, a form of Flatstyle directors. painting that flourished in the 20th Elizondo received his BFA from century and continues today. Michael Oklahoma Baptist University (OBU) in Elizondo Jr. (Cheyenne/Kaw/Chumash) 2008 and his MFA from the University now serves as the new art director of the of Oklahoma (OU) in 2011. At OBU Bacone College School of Indian Art. -

America Meredith

AMERICA MEREDITH Tribal Affiliation: Cherokee Contact Exhibit C Native Gallery & Gifts for pricing America Meredith is the publishing editor of First American Magazine and is an educator, author, artist and independent curator whose curatorial practice spans more than two decades. Meredith earned her Master of Fine Arts degree from San Francisco Art Institute and her Bachelor of Fine Arts with distinction from the University of Oklahoma. She has taught art history courses at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe Community College and the Cherokee Humanities Clemente Program. Meredith has exhibited across the United States as well as internationally. Her work is in major public collections including those of the National Museum of the American Indian, National Collection of Contemporary Indian Arts, Cherokee Nation Historical Society, Eiteljorg Museum, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Heard Museum, Red Cloud Heritage Center, Southern Plains Indian Museum, St. Paul’s Cathedral, Sequoyah National Research Center and Tweed Museum of Art. In the last 20 years, Meredith has won numerous awards at the Heard Museum, SWAIA’s Indian Market, Cherokee Heritage Center, Cahokia Mounds and other competitive shows. She was a National Museum of the American Indian Fellow in 2009, won the IAIA Distinguished Alumni Award for Excellence in Contemporary Native American Arts in 2007 and was voted SF Weekly’s Painter of the Year in 2006. Currently, Meredith serves on the board of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian and the Cherokee Arts and Humanities Council. She is represented by Spider Gallery in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and Rainmaker Art Gallery in Bristol, England, United Kingdom. -

Studio School Multi-Week Classes Syllabi and Supply Lists Spring Session (April–June 2021) Updated 2/26/21

Studio School Multi-Week Classes Syllabi and Supply Lists Spring Session (April–June 2021) Updated 2/26/21 Table of Contents Click on links below OR use your computer’s find function (CTRL+F) to jump to your desired course listing. Sections are ordered in alphabetical order and/or by day of class. GENERAL INFORMATION ...................................................................................... 3 Class Cancellations and Makeup Days ............................................................................ 3 COVID-19 Safety Guidelines ............................................................................................. 3 Online Courses .................................................................................................................... 4 Outdoor Classes ................................................................................................................. 4 Registration in Studio School .......................................................................................... 4 Rentals and Onsite Purchases .......................................................................................... 5 Studio Policies .................................................................................................................... 5 2-D MEDIA ................................................................................................................ 6 Beginning Acrylic Painting ............................................................................................... 6 Beginning Drawing -

The Rebirth of Southeastern Woodlands Beadwork

garters are primarily sewn on blue or red brought in 18th-century southeastern wool stroud, backed by calico. beadwork from Scotland that had not been in the Americas in over two centuries. She White is the predominant color for the brought in the work of other southeastern beads; imported glass beads replaced beadworkers, such as Jerry Ingram and precontact pearl and shell beads. Many Brian Zepeda. designs are simply red, blue, and black, but others have wild palettes of pinks, Seeing was believing. While still only Stitches greens, golds, pastels—all arranged for a few dozen people bead Southeastern maximum visual impact. The fluid designs Woodlands-style beadwork, the are abstract, floral, zoomorphic, and very numbers are far larger than they were rarely anthropomorphic. They have been 15 years ago, and the knowledge of the compared to one-celled organisms viewed beadwork among the tribes has jumped through a microscope. exponentially. I interviewed four beadwork artists instrumental in this in Time: The “Golden Era” of Southeastern remarkable revival to get their stories. Woodlands beadwork was the late 18th century until the Removal Era in the The Rebirth of 1830s. Alabama, Koasati, Cherokee, Jerry Ingram Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, “When I was a kid, I was interested in Natchez, Seminole, and Yuchi people were beadwork,” says Jerry Ingram, “and the forcibly removed from their southeastern Southeastern only place I saw any was the department homelands to Indian Territory, now Jerry Ingram (Choctaw). Photo: A. Meredith store in Idabel.” An enrolled member of Oklahoma. Some tribes stayed in the the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Ingram southeast, and today Southeastern with Powwow Highway. -

JOHN HITCHCOCK • Hybridpress • University of Wisconsin-Madison

JOHN HITCHCOCK • Hybridpress • University of Wisconsin-Madison 455 North Park Street • 6101 Mosse Humanities Building• Madison, Wisconsin 53706 • [email protected] www.hybridpress.net EDUCATION 1997 M.F.A. Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas. Printmaking/Photography/Painting 1990 B.F.A. Cameron University Lawton, Oklahoma. Printmaking/Drawing. CURRENT EMPLOYMENT 2016- present University of Wisconsin-Madison Associate Dean for the Arts, School of Education 2014- 2016 University of Wisconsin-Madison Faculty Director, The Studio-Creative Arts & Design Community 2001-present University of Wisconsin-Madison Professor (2011-present), Associate Professor of Art (2006- 2011), Assistant Professor (2001-2006). Relief/Screenprinting/Installation Art GRANTS, HONORS, AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS RESIDENCIES (SELECTED) 2016-18 Emily Mead Baldwin Award in the Creative Arts University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2012-15 The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Artistic Innovation and Collaboration grant, New York. 2011-13 Arts Institute Creative Arts Award, University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2011 Venice Printmaking Studio, Venice, Italy. (Residency) 2009 Frans Masereel Centrum for Graphix Kasterlee, Belgium. (Residency) 2008 Proyecto’ace, International Center for Visual arts in South America Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Residency) 2007 Vermont Studios Center Residency Full Fellowship, Johnson, Vermont. (Residency) 2005 Cultural Collision! U.S.–N.Z. Arts Residency/Workshop at the ‘Te Kura Toi O Buck Nin –Buck Nin School of Arts’ Te Wananga O Aotearoa, Auckland, New Zealand. (Residency) 2005 Te Mata Gathering of Contemporary Indigenous Visual Artists Residency/Workshop/Exhibition, Toimairangi School of Maori Visual Culture Te Wananga o Aotearoa, Hastings, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. 2004 CitiArts Grant Shared with Derrick Busich. Madison, Wisconsin. 03-05 Vilas Associate Grant The Graduate School, University of Wisconsin-Madison. -

Linda Lomahaftewa

PROFILE LINDA LOMAHAFTEWA to painting and began working in oils. Astonishingly, Hopi Spirits and Unknown Spirits are two of her first paintings, HOPI/CHOCTAW PRINTMAKER AND PAINTER completed when she was only 18 years old. They each express her connection to place through absence and presence. LINDA LOMAHAFTEWA An abstract vision of Hopi spirits gaze from an intimate distance outward and By Jean Merz-Edwards amplify Lomahaftewa’s absence from her home in Arizona. In contrast, a distant “For decades Linda has been a promi- Lomahaftewa, in the spring of 1961, “I got view of mountains—much like the Sangre nent figure in contemporary Native art. a phone call from my mom, and she read de Cristo Mountains visible from Santa Her paintings demonstrate a wonderful in the paper that they would be opening Fe—solidify Lomahaftewa’s presence in a strength informed by her culture placed up this new Indian art school in Santa Fe, place with unknown spirits. Finally, they in a contemporary context.”1 and it’ll be headed up by Lloyd New, who denote the starting point of a journey —Joe Feddersen (Okanagan/Sinixt) was one of her teachers when she went centering Lomahaftewa within the story [to the] Phoenix Indian School.”3 That of Native American art. PPORTUNITY RARELY summer Lomahaftewa and her mother AFFORDS us the benefit of filled out the application. In the fall of CALIFORNIA DAYS visiting with a living legend. 1962, Lomahaftewa began her sophomore “I WAS TAUGHT to believe in myself, Whether it be the scarcity O year in the first high school class at the that’s how I grew up,” Lomahaftewa of such individuals or our proximity to Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA).