Linda Lomahaftewa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation

CREATING AN OSAGE FUTURE: ART, RESISTANCE, AND SELF-REPRESENTATION Jami C. Powell A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Jean Dennison Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld Valerie Lambert Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote Chip Colwell © 2018 Jami C. Powell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jami C. Powell: Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation (Under the direction of Jean Dennison and Rudolf Colloredo Mansfeld) Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation, examines the ways Osage citizens—and particularly artists—engage with mainstream audiences in museums and other spaces in order to negotiate, manipulate, subvert, and sometimes sustain static notions of Indigeneity. This project interrogates some of the tactics Osage and other American Indian artists are using to imagine a stronger future, as well as the strategies mainstream museums are using to build and sustain more equitable and mutually beneficial relationships between their institutions and Indigenous communities. In addition to object-centered ethnographic research with contemporary Osage artists and Osage citizens and collections-based museum research at various museums, this dissertation is informed by three recent exhibitions featuring the work of Osage artists at the Denver Art Museum, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma. Drawing on methodologies of humor, autoethnography, and collaborative knowledge-production, this project strives to disrupt the hierarchal structures within academia and museums, opening space for Indigenous and aesthetic knowledges. -

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

Newsletter Fall 2011 DATED Decorative Arts Society Arts Decorative Secretary C/O Lindsy R

newsletter fall 2011 Volume 19, Number 2 Decorative Arts Society DAS Newsletter Volume 19 Editor Gerald W.R. Ward Number 2 Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator Fall 2011 of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture The DAS Museum of Fine Arts, Boston The DAS Newsletter is a publication of Boston, MA the Decorative Arts Society, Inc. The pur- pose of the DAS Newsletter is to serve as a The Decorative Arts Society, Inc., is a not- forum for communication about research, Coordinator exhibitions, publications, conferences and Ruth E. Thaler-Carter in 1990 for the encouragement of interest other activities pertinent to the serious Freelance Writer/Editor in,for-profit the appreciation New York of,corporation and the exchange founded of study of international and American deco- Rochester, NY information about the decorative arts. To rative arts. Listings are selected from press pursue its purposes, the Society sponsors releases and notices posted or received Advisory Board meetings, programs, seminars, and a news- from institutions, and from notices submit- Michael Conforti letter on the decorative arts. Its supporters ted by individuals. We reserve the right to Director include museum curators, academics, col- reject material and to edit materials for Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute lectors and dealers. length or clarity. Williamstown, MA The DAS Newsletter welcomes submis- Officers sions, preferably in digital format, submit- Wendy Kaplan President ted by e-mail in Plain Text or as Word Department Head and Curator, David L. Barquist attachments, or on a CD and accompanied Decorative Arts H. Richard Dietrich, Jr., Curator by a paper copy. -

1Cljqpgni 843713.Pdf

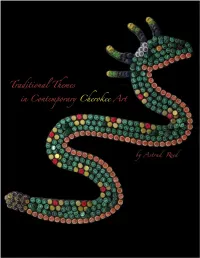

© 2013 University of Oklahoma School of Art All rights reserved. Published 2013. First Edition. Published in America on acid free paper. University of Oklahoma School of Art Fred Jones Center 540 Parrington Oval, Suite 122 Norman, OK 73019-3021 http://www.ou.edu/finearts/art_arthistory.html Cover: Ganiyegi Equoni-Ehi (Danger in the River), America Meredith. Pages iv-v: Silent Screaming, Roy Boney, Jr. Page vi: Top to bottom, Whirlwind; Claflin Sun-Circle; Thunder,America Meredith. Page viii: Ayvdaqualosgv Adasegogisdi (Thunder’s Victory),America Meredith. Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art Traditional Themes in Contemporary Cherokee Art xi Foreword MARY JO WATSON xiii Introduction HEATHER AHTONE 1 Chapter 1 CHEROKEE COSMOLOGY, HISTORY, AND CULTURE 11 Chapter 2 TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTS AND UTILITARIAN ITEMS INTO ART 19 Chapter 3 CONTEMPORARY CHEROKEE ART THEMES, METHODS, AND ARTISTS 21 Catalogue of the Exhibition 39 Notes 42 Acknowledgements and Contributors 43 Bibliography Foreword "What About Indian Art?" An Interview with Dr. Mary Jo Watson Director, School of Art and Art History / Regents Professor of Art History KGOU Radio Interview by Brant Morrell • April 17, 2013 Twenty years ago, a degree in Native American Art and Art History was non-existent. Even today, only a few universities offer Native Art programs, but at the University of Oklahoma Mary Jo Watson is responsible for launching a groundbreaking art program with an emphasis on the indigenous perspective. You expect a director of an art program at a major university to have pieces in their office, but entering Watson’s workspace feels like stepping into a Native art museum. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2010 July 1, 2009–June 30, 2010

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2010 July 1, 2009–June 30, 2010 For the 2009–2010 fiscal year, Tacoma Art Museum presented a series of exhibitions focusing on its mission of “emphasizing the art and artists of the Northwest” alongside nationally and internationally acclaimed artists across all media. The summer of 2009 began with the dynamic pairing of jewelry exhibitions, Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, the only West Coast venue of the major exhibi- tion organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Loud Bones: The Jewelry of Nancy Worden, which was curated by Ta- coma Art Museum. The autumn exhibitions included A Concise History of Northwest Art, featuring highlights of the museum’s Northwest art collection and exploring the development of the region’s art from the 1890s to the present. Joe Feddersen: Vital Signs, organized by Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University, presented a retrospective look at Native American art- ist Joe Feddersen, a nationally acclaimed printmaker, basket maker, and glass artist. One of the museum’s most treasured col- lections was featured in The Movement of Impressionism: Europe, America, and the Northwest, a survey of how a painting style spread from late 19th-century Paris to the Northwest. The museum’s works by Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Au- guste Renoir along with works by Everett Shinn, Maurice Prendergast, and others were supplemented by important loans of Northwest impressionists. The winter season featured The Secret Language of Animals, a two-gallery exhibition exploring the changing ways artists used animals as symbols for human relationships across three centuries of American and European art. -

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

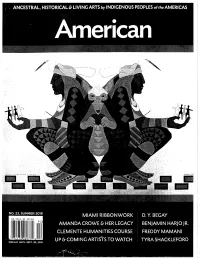

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

FROELICK GALLERY Joe Feddersen Born 1953 Omak, WA

FROELICK GALLERY Joe Feddersen Born 1953 Omak, WA Tribal Affiliation The Confederated Tribes of The Colville Reservation (Okanagan and Lakes) Education 1989 Master of Fine Arts, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WA 1983 BFA Printmaking, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 1979 A.A. Applied Arts, Wenatchee Valley College, Wenatchee, WA Solo Exhibitions 2021 Inhabited Landscapes, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR 2020 Two Generations: Joe Feddersen and Wendy Red Star, Schneider Museum of Art, Southern Oregon University, Ashland, OR 2019 Echo, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR Echo, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR 2018 Cultural Abstractions, curated by Todd Clark, Umpqua Valley Arts Association, Roseburg, OR Joe Feddersen, Graves Gallery, Wenatchee Valley College, Wenatchee, WA 2017 Flotilla, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR 2015 Canoe Journeys, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR 2014 Matrix, Spokane Falls Community College, Spokane ,WA 2013 Charmed, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR 2012 Role Call, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR Terrain, Larson Gallery, Yakima Valley Community College, Yakima, WA (catalogue) Transitions, MAC Gallery, Wenatchee Valley College, Wenatchee, WA 2010 Codex, Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR Codex, Evergreen Gallery, TESC, Olympia WA, (catalogue) Vital Signs, Hallie Ford Museum, Willamette University, Salem, OR 2009 Vital Signs, Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA, organized by Hallie Ford Museum of Art Codex, Evergreen Gallery, Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA 2008 Vital Signs, Missoula Art Museum, Missoula, MT, -

Five-Year Report

five-year report Letter From the Board Chair Dear Friends, he 5th anniversary of our new home interdisciplinary mix, from workshops and is an extraordinary moment for the tours to performances and screenings. Museum of Arts and Design. With a Growing our permanent collection three- dynamic roster of exhibitions and fold, under Holly and David’s leadership, allows programs planned, a loyal base of us to offer richer and deeper exhibitions for our friends and supporters and new visitors. Encompassing traditional forms of Lewis Kruger leadership at the helm, we couldn’t craftsmanship, including works made in clay, chairman, board of trustees; be more excited about all that we glass, wood, metal and fiber, as well as works museum of have ahead. Together with our of art and design created with innovative new arts and design dedicated board, so many important donors, materials and processes, the collection now Tour 8,000-strong base of loyal members and our establishes a bridge between legendary craft talented staff, it has been a remarkable process figures and a new generation of makers. to build not just a new building, but a new It is fully digitized and can be accessed online institution. I want to thank Holly Hotchner, who by our global community as well as through led the Museum for 16 years before stepping innovative in-gallery formats, as so many down this spring, and our chief curator David of you have experienced. McFadden, who will be retiring at the end of Our robust special exhibition program this year after a 16-year tenure; as well as my has transformed traditional ideas about craft, fellow members of our board trustees, especially including a series of critically acclaimed Jerome A. -

PROSPECTUS Entry Guidelines & Form Artwork Entry Date: Saturday, May 12Th, 2018

Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center Presents North Central Washington Juried Art Show June 1st, 2018 to September 8th, 2018 ARTIST PROSPECTUS Entry Guidelines & Form Artwork Entry Date: Saturday, May 12th, 2018 The 3rd NCW Juried Art Show presented by the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center and the Wenatchee Arts, Recreation and Parks Commission showcases quality work by regional artists in a museum gallery. The art show opens during the First Friday Artwalk of June on Friday, June 1st from 5 – 8 p.m. This year’s event highlights area artists of both two-dimensional and three-dimensional original works of art that will be on display and for sale. The reception will take place at Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center, 127 South Mission Street, Wenatchee. The opening reception is free and open to the public. The Juried Fine Art Exhibit will be open to the public regularly beginning Friday June 1st from 10 a.m. – 8 p.m. and continue on display through the first Friday of September. A closing reception with announcement of the People's Choice Award winner (at 6 p.m.) will take place that evening, Friday, September 7th during the Artwalk from 5 – 8 p.m. Admission is free and open to the public. Art will be returned to the artists no earlier than 10 a.m. on Saturday, September 8th at the Wenatchee Valley Museum, 127 S Mission Street, Wenatchee. Artists or their designated representative must be available to pick up their artwork between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. on September 8th to be eligible to enter the show. -

2008-2009 Annual Review

School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience The Long View Santa Fe, New Mexico Annual Review 2008–2009 School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience Santa Fe, New Mexico Annual Review 2009 The School for Advanced Research gratefully acknowledges the very generous support of the Paloheimo Foundation for publication of this report. The foundation’s grant honors the late Leonora Paloheimo and her mother, Leonora Curtin, who served on the Board of Managers of the School from 1933 to 1972. CONTENTS President’s Message: The Long View 4 Cultivating the Long View: SAR Programs 6 TIME Dean Falk: Riddling the Bones 10 Wenda Trevathan: Evolutionary Medicine and Women’s Health 11 Timothy R. Pauketat: An Archaeology of the Cosmos 12 Daniel J. Hoffman: Building the Barracks 13 Audra Simpson: To the Reserve and Back Again 14 Cedar Sherbert, King Native Artist Fellow 15 Jessica Metcalfe, Branigar Native Intern 16 Pat Courtney Gold, Dobkin Native Artist Fellow 17 Ulysses Reid, Dubin Native Artist Fellow 18 NEW BOOKS FROM SAR PRESS Visiting Research Associates 19 Democracy 35 Summer Scholars 20 Confronting Cancer 36 Aboriginal Business 37 CONNECTION The Ancient City 38 Symposium: Corporate Lives 22 Figuring the Future 39 Advanced Seminar: The Middle Classes 23 Timely Assets 40 Advanced Seminar: Markets and Moralities 24 The Great Basin 41 Advanced Seminar: Colonial and Postcolonial Discover the Digital SAR 42 Change in Mesoamerica 25 Indian Arts Research Center: COMMUNITY Connecting Artists, Scholars, and Tradition 26 Off the Beaten Path: -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By DENISE NEIL-BINION Norman, Oklahoma 2017 REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION: DEPICTIONS OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN OKLAHOMA POST OFFICE MURALS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. Mary Jo Watson, Chair ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing III ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Swan © Copyright by DENISE NEIL-BINION 2017 All Rights Reserved. For the many people who instilled in me a thirst for knowledge. Acknowledgements I wish to extend my sincerest appreciation to my dissertation committee; I am grateful for the guidance, support, and mentorship that you have provided me throughout this process. Dr. Mary Jo Watson, thanks for being a mentor and a friend. I also must thank Thomas Lera, National Postal Museum (retired) and RoseMaria Estevez of the National Museum of the American Indian. The bulk of my inspiration and research developed from working with them on the Indians at the Post Office online exhibition. I am also grateful to the Smithsonian Office of Fellowships and Internships for their financial support of this endeavor. To my friends and colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, your friendship and support are truly appreciated. Tammi Hanawalt, heather ahtone, and America Meredith thank you for your encouragement, advice, and most of all your friendship. To the 99s Museum of Women Pilots, thanks for allowing me so much flexibility while I balanced work, school, and life.