The Age of Aquarius: the Reorientation of NASA After 1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

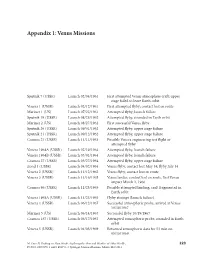

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office May 1988

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE MAY 1988 A SPECIAL STUDY THE NASA PROGRAM IN THE 1990s AND BEYOND The Congress of the United States Congresssional Budget Of'f'ice NOTES All costs are expressed in 1988 dollars of budget authority, unless otherwise noted. All years are fiscal years, except when applied to launch schedules. PREFACE The United States space program stands at a crossroads. The momentum of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) program over the last 20 years has brought NASA to a point where new activities will require substantial increases in the agency's budget. Critics of the NASA program have called for even more ambi- tious goals, most prominently an expansion of manned space flight to the Moon or Mars. Fiscal concerns, however, may limit even the more modest set of activities envisioned by NASA. This special study, requested by the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Trans- portation, examines the broad options for the U.S. space program in the 1990s. In keeping with the mandate of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to provide objective nonpartisan analysis, the report makes no recommendations. David H. Moore, of CBO's Natural Resources and Commerce Division, prepared the report under the supervision of Everett M. Ehrlich. Frances M. Lussier of CBO's National Security Division and Michael Sieverts of CBO's Budget Analysis Division provided valu- able comments and assistance. Many outside reviewers made useful comments and criticisms. Amanda Balestrieri edited the manuscript. Margaret Cromartie prepared early drafts of the report, and Kathryn Quattrone prepared the final draft for publication. -

+ New Horizons

Media Contacts NASA Headquarters Policy/Program Management Dwayne Brown New Horizons Nuclear Safety (202) 358-1726 [email protected] The Johns Hopkins University Mission Management Applied Physics Laboratory Spacecraft Operations Michael Buckley (240) 228-7536 or (443) 778-7536 [email protected] Southwest Research Institute Principal Investigator Institution Maria Martinez (210) 522-3305 [email protected] NASA Kennedy Space Center Launch Operations George Diller (321) 867-2468 [email protected] Lockheed Martin Space Systems Launch Vehicle Julie Andrews (321) 853-1567 [email protected] International Launch Services Launch Vehicle Fran Slimmer (571) 633-7462 [email protected] NEW HORIZONS Table of Contents Media Services Information ................................................................................................ 2 Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................. 3 Pluto at a Glance ...................................................................................................................... 5 Why Pluto and the Kuiper Belt? The Science of New Horizons ............................... 7 NASA’s New Frontiers Program ........................................................................................14 The Spacecraft ........................................................................................................................15 Science Payload ...............................................................................................................16 -

Solar System Exploration: a Vision for the Next Hundred Years

IAC-04-IAA.3.8.1.02 SOLAR SYSTEM EXPLORATION: A VISION FOR THE NEXT HUNDRED YEARS R. L. McNutt, Jr. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Laurel, Maryland, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT The current challenge of space travel is multi-tiered. It includes continuing the robotic assay of the solar system while pressing the human frontier beyond cislunar space, with Mars as an ob- vious destination. The primary challenge is propulsion. For human voyages beyond Mars (and perhaps to Mars), the refinement of nuclear fission as a power source and propulsive means will likely set the limits to optimal deep space propulsion for the foreseeable future. Costs, driven largely by access to space, continue to stall significant advances for both manned and unmanned missions. While there continues to be a hope that commercialization will lead to lower launch costs, the needed technology, initial capital investments, and markets have con- tinued to fail to materialize. Hence, initial development in deep space will likely remain govern- ment sponsored and driven by scientific goals linked to national prestige and perceived security issues. Against this backdrop, we consider linkage of scientific goals, current efforts, expecta- tions, current technical capabilities, and requirements for the detailed exploration of the solar system and consolidation of off-Earth outposts. Over the next century, distances of 50 AU could be reached by human crews but only if resources are brought to bear by international consortia. INTRODUCTION years hence, if that much3, usually – and rightly – that policy goals and technologies "Where there is no vision the people perish.” will change so radically on longer time scales – Proverbs, 29:181 that further extrapolation must be relegated to the realm of science fiction – or fantasy. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

Apollo 13 Mission Review

APOLLO 13 MISSION REVIEW HEAR& BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON AERONAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FIRST CONGRESS SECOR’D SESSION JUR’E 30, 1970 Printed for the use of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 47476 0 WASHINGTON : 1970 COMMITTEE ON AEROKAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES CLINTON P. ANDERSON, New Mexico, Chairman RICHARD B. RUSSELL, Georgia MARGARET CHASE SMITH, Maine WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washington CARL T. CURTIS, Nebraska STUART SYMINGTON, bfissouri MARK 0. HATFIELD, Oregon JOHN STENNIS, Mississippi BARRY GOLDWATER, Arizona STEPHEN M.YOUNG, Ohio WILLIAM B. SAXBE, Ohio THOJfAS J. DODD, Connecticut RALPH T. SMITH, Illinois HOWARD W. CANNON, Nevada SPESSARD L. HOLLAND, Florida J4MES J. GEHRIG,Stad Director EVERARDH. SMITH, Jr., Professional staffMember Dr. GLENP. WILSOS,Professional #tad Member CRAIGVOORHEES, Professional Staff Nember WILLIAMPARKER, Professional Staff Member SAMBOUCHARD, Assistant Chief Clerk DONALDH. BRESNAS,Research Assistant (11) CONTENTS Tuesday, June 30, 1970 : Page Opening statement by the chairman, Senator Clinton P. Anderson-__- 1 Review Board Findings, Determinations and Recommendations-----_ 2 Testimony of- Dr. Thomas 0. Paine, Administrator of NASA, accompanied by Edgar M. Cortright, Director, Langley Research Center and Chairman of the dpollo 13 Review Board ; Dr. Charles D. Har- rington, Chairman, Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel ; Dr. Dale D. Myers, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, and Dr. Rocco A. Petrone, hpollo Director -___________ 21, 30 Edgar 11. Cortright, Chairman, hpollo 13 Review Board-------- 21,27 Dr. Dale D. Mvers. Associate Administrator for Manned SDace 68 69 105 109 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIOSS 1. Internal coinponents of oxygen tank So. 2 ---_____-_________________ 22 2. -

Extensions of Remarks 3561

February 17, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 3561 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE RACE TO THE MOON Space experts say that unless we are will ing from one table to another, looking at a ing to maintain a stable, continuing space large book on each of two tables and shaking program in the coming decade we stand in his head. The Keeper looked and saw that his HON. GEORGE P. MILLER danger of squandering the $32 billion already smart monkey was reading Darwin's "Origin OF CALIFORNIA invested in the U.S. space program. of the Species" on one table and the "Holy Werner von Braun, director of the Mar Bible" on the other. The Keeper then asked IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES shall Space Flight Center, recently predicted the monkey why he kept shaking his head. Monday, February 17, 1969 the U.S. budget reductions will permit the The monkey replied: I'm trying to find out Russians "to fly rings around us in space in if I am my brother's keeper or my keeper's Mr. MILLER of California. Mr. Speak a period of five years." He contended it would brother." er, just before the epoch-making fiight take steady spending of $5 billion to $6 bil The moral for the evening is that back of Saturn V around the moon, the Oak lion a year for the U.S. to pull even; pro here in the State of my birth, Iowa's Gov land Tribune published an editorial en grams costing only up to $4 billion "simply ernor's Committee knows that it is both it's titled, "The Race to the Moon: Will It guarantee our falling back." brother's keeper and it's keeper's brother. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G.