No.679 (August Issue)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

The Dogen Canon D 6 G E N ,S Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1997 24/1-2 The Dogen Canon D 6 g e n ,s Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works Steven H eine Recent scholarship has focused on the question of whether, and to what extent, Dogen underwent a significant change in thought and attitudes in nis Later years. Two main theories have emerged which agree that there was a decisive change although they disagree about its timing and meaning. One view, which I refer to as the Decline Theory, argues that Dogen entered into a prolonged period of deterioration after he moved from Kyoto to Echizen in 1243 and became increasingly strident in his attacks on rival lineages. The second view, which I refer to as the Renewal Theory, maintains that Dogen had a spiritual rebirth after returning from a trip to Kamakura in 1248 and emphasized the priority of karmic causality. Both theories, however, tend to ignore or misrepresent the early writings and their relation to the late period. I will propose an alternative Three Periods Theory suggesting that the main change, which occurred with the opening of Daibutsu-ji/Eihei-ji in 1245, was a matter of altering the style of instruc tion rather than the content of ideology. At that point, Dogen shifted from the informal lectures (jishu) of the Shdbdgenzd,which he stopped deliver ing, to the formal sermons (jodo) in the Eihei koroku, a crucial later text which the other theories overlook. I will also point out that the diversity in literary production as well as the complexity and ambiguity of historical events makes it problematic for the Decline and Renewal theories to con struct a view that Dogen had a single, decisive break with his previous writings. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1996 23/3-4 The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law Kuroda Toshio Translated by Jacqueline I. Stone Buddhism has often been regarded in purely intellectual or spiritual terms. However, especially in its institutional dimensions, Buddhism like other religious traditions has been closely associated with political authority, and to ignore this is to distort its history. To begin redressing scholarly neglect of this subject, the late Kuroda Toshio explores in this article the paired concepts of the obo (imperial law) and the buppo (Buddhist law) as an interpretive framework for investigating Buddhism's political role in the Japanese historical context. The doctrine of the mutual dependence of the imperial law and the Buddhist law (obo buppo sdiron) emerged toward the latter part of the eleventh century, in connection with the development of the estate system (shoen seido) of land tenure. As powerful landholders, the major temple-shrlne complexes of Japan's early medieval period consti tuted a political force that periodically challenged the authority of the emperor, the court, and the leading warrior houses, but on the other hand cooperated with these influential parties in a system of shared rule. This system actively involved Buddhist institutions in maintenance of the sta tus quo and was criticized in various ways by the leaders of the Kamakura new Buddhist movements, who asserted that the buppo should transcend worldly authority. However, such criticisms were never fully implemented, and after the medieval period, Buddhism came increasingly under the domination of central governing powers. The relationship of Buddhism to political authority is a troubling problem in Japanese history and remains unresolved to this day. -

No.729 (October Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 729 October, 2017 MEITO KANSHO: EXAMINATION OF IMPORTANT SWORDS Juyo Bunkazai Type: Tachi Mei: Chikakane Owner: Hayashibara Museum Length: 2 shaku 5 sun 3 bu 1 rin (76.7 cm) Sori: 7 bu 6 rin (2.3 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 2 rin (2.8 cm) Sakihaba: 5 bu 6 rin (1.7 cm) Motokasane: 2 bu 3 rin (0.7 cm) Sakikasane: 1 bu 2 rin (0.35 cm) Kissaki length: 9 bu 9 rin (3.0 cm) Nakago length: 7 sun 5 bu 9 rin (23.0 cm) Nakago sori: 5 rin (0.15 cm) Commentary This is a shinogi zukuri tachi with an ihorimune, a standard width, and the widths at the moto and saki are different. The tachi is slightly thick for its width. There is a large koshi-zori with funbari and there is a small kissaki. The jihada is ko-itame mixed with itame and mokume, and the jihada is barely visible. There are ji-nie, fine chikei, and utsuri. The hamon is a wide suguha, At the koshimoto, it is mixed with ko-gunome with vertical undulations. There is a dense nioiguchi. Above the koshimoto there is a shallow and small notare with a tight nioiguchi. There are ashi and yo, mainly at the bottom half of the tachi, and the entire hamon is nioi-deki (based on nioi). The boshi is straght and almost yakizume, and the entire boshi is yaki-kuzure (composed of crumbled nie) with hakikake, and a very small return. The nakago is ubu, and the nakago tip is ha-agari kuri-jiri. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Tsuda Sōkichi Vs. Orikuchi Shinobu

Japanese G9040 Graduate Seminar on Premodern Japanese Literature, Spring 2016: Tsuda Sōkichi vs. Orikuchi Shinobu Wednesdays 4:10-6:00pm; 522A Kent Hall David Lurie <[email protected]> Office Hours: Tues. 2-3 & Thurs. 11-12 in 500C Kent Hall Course Rationale: This course treats Tsuda Sōkichi (1873-1961) and Orikuchi Shinobu (1887-1953) as twin titans of twentieth-century scholarship on ancient Japan. In fields as diverse as literature, history of thought, religious studies, mythology, ancient history, poetry, Chinese studies, and drama, their influence remains strong today. Tsuda’s ideas still shape mainstream approaches to Japanese mythology and early historical works, and terms and concepts created by Orikuchi are central to national literary studies (kokubungaku), even if their derivation from his work is often forgotten. It is hard to imagine two scholars more different in approach and style: Tsuda the systematic, skeptical positivist versus Orikuchi the intuitive, speculative romantic. And yet they repeatedly addressed similar questions and problems, and despite Tsuda’s earlier birth and longer life, their periods of greatest productivity (Taishō to early Shōwa, with important codas in the decade or so after the war) also overlapped. Accordingly this syllabus imagines a dialogue between them by juxtaposing selections from key works. Because the oeuvres of Tsuda and Orikuchi are so enormous (put together, their collected works reach 75 volumes) and their interests so varied, it is impossible to provide a systematic overview here. The selection is focused on early Japan, and much has been left out, such as Orikuchi’s work on poetry and drama, or Tsuda’s studies of Buddhism and classical Chinese philosophy. -

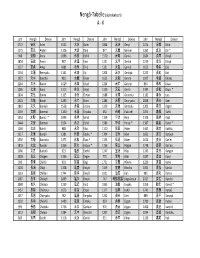

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Bungei Shunjū in the Early Years and the Emergence

THE EARLY YEARS OF BUNGEI SHUNJŪ AND THE EMERGENCE OF A MIDDLEBROW LITERATURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Minggang Li, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Richard Torrance, Adviser Professor William J. Tyler _____________________________ Adviser Professor Kirk Denton East Asian Languages and Literatures Graduate Program ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the complex relationship that existed between mass media and literature in pre-war Japan, a topic that is largely neglected by students of both literary and journalist studies. The object of this examination is Bungei shunjū (Literary Times), a literary magazine that played an important role in the formation of various cultural aspects of middle-class bourgeois life of pre-war Japan. This study treats the magazine as an organic unification of editorial strategies, creative and critical writings, readers’ contribution, and commercial management, and examines the process by which it interacted with literary schools, mainstream and marginal ideologies, its existing and potential readership, and the social environment at large. In so doing, this study reveals how the magazine collaborated with the construction of the myth of the “ideal middle-class reader” in the discourses on literature, modernity, and nation in Japan before and during the war. This study reads closely, as primary sources, the texts that were published in the issues of Bungei shunjū in the 1920s and 1930s. It then contrasts these texts with ii other texts published by the magazine’s peers and rivals. -

The Ichikawa and Warrior Family Dynamics In

ALPINE SAMURAI: THE ICHIKAWA AND WARRIOR FAMILY DYNAMICS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL JAPAN by KEVIN L. GOUGE A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2009 ii “Alpine Samurai: The Ichikawa and Warrior Family Dynamics in Early Medieval Japan,” a thesis prepared by Kevin L. Gouge in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Goble, Chair of the Examining Committee ________________________________________ Date Committee in Charge: Dr. Andrew Goble, Chair Dr. Jeffrey Hanes Dr. Peggy Pascoe Accepted by: ____________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School iii © 2009 Kevin L. Gouge iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Kevin L. Gouge for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History to be taken June 2009 Title: ALPINE SAMURAI: THE ICHIKAWA AND WARRIOR FAMILY DYNAMICS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL JAPAN Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Goble This study traces the property lineage of the Ichikawa family of Japan’s Shinano province from the early 1200s through the mid-1300s. The property portfolio originated in complicated inheritance dynamics in the Nakano family, into which Ichikawa Morifusa was adopted around 1270. It is evident that Morifusa, family head for the next fifty years, was instrumental in establishing a solid foundation for the Ichikawa’s emergence as a powerful warrior clan by 1350. This study will begin with a broad interpretation of the concept of warrior “family” as reflected in a variety of primary sources, followed by an in-depth case study of six generations of the Nakano/Ichikawa lineage.