From Polyjurality to Monojurality: the Transformation of Quebec Law, 1875-1929

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Wednesday, October 1, 1997

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 008 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, October 1, 1997 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the followingaddress: http://www.parl.gc.ca 323 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, October 1, 1997 The House met at 2 p.m. Columbians are crying out for federal leadership and this govern- ment is failing them miserably. _______________ Nowhere is this better displayed than in the Liberals’ misman- Prayers agement of the Pacific salmon dispute over the past four years. The sustainability of the Pacific salmon fishery is at stake and the _______________ minister of fisheries sits on his hands and does nothing except criticize his own citizens. D (1400) Having witnessed the Tory government destroy the Atlantic The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesday we will now sing fishery a few years ago, this government seems intent on doing the O Canada, and we will be led by the hon. member for Souris— same to the Pacific fishery. Moose Mountain. It is a simple case of Liberal, Tory, same old incompetent story. [Editor’s Note: Members sang the national anthem] This government had better wake up to the concerns of British Columbians. A good start would be to resolve the crisis in the _____________________________________________ salmon fishery before it is too late. * * * STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS TOM EDWARDS [English] Ms. Judi Longfield (Whitby—Ajax, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I rise today to recognize the outstanding municipal career of Mr. -

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution Armand L. C. de Mestral and William Fraiberg * Introduction An official language may be defined as one ordained by law to be used in the public institutions of a state; more particularly in its legislature and laws, its courts, its public administration and its public schools.1 In Canada, while language rights have historically been an issue of controversy, only a partial provision for official languages as above defined is to be found in the basic constitutional Acts. The British North America Act, in sec. 133,2 gives limited re- cognition to both Engish and French in the courts, laws, and legis- latures of Canada and Quebec. With the possible exception of Quebec, the Provinces would appear to have virtually unlimited freedom to legislate with respect to language in all spheres of public activity within their jurisdiction. English is the "official" language of Mani- toba by statute 3 and is the language of the courts of Ontario.4 While Alberta and Saskatchewan have regu'ated the language of their schools,5 they have not done so with respect to their courts and • Of the Editorial Board, McGill Law Journal; lately third law students. 'The distinction between an official language and that used in private dis- course is clearly drawn by the Belgian Constitution: Art. 23. "The use of the language spoken in Belgium is optional. This matter may be regulated only by law and only for acts of public authority and for judicial proceedings." Peaslee, A. J., Constitutions of Nations, Concord, Rumford Press, 1950, p. -

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to The

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage By The Fédération nationale des communications – CSN April 18, 2016 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The role of the media in our society ..................................................................................................................... 7 The informative role of the media ......................................................................................................................... 7 The cultural role of the media ................................................................................................................................. 7 The news: a public asset ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Recent changes to Quebec’s media landscape .................................................................................................. 9 Print newspapers .................................................................................................................................................... -

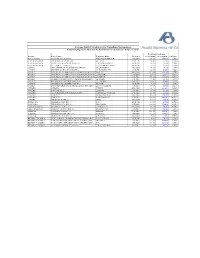

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures As Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures as Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit Total Paid Circulation Province City (County) Newspaper Name Frequency As of 9/30/09 As of 9/30/08 % Change NOVA SCOTIA HALIFAX (HALIFAX CO.) CHRONICLE-HERALD AVG (M-F) 108 182 110 875 -2,43% NEW BRUNSWICK FREDERICTON (YORK CO.) GLEANER MON-FRI 20 863 21 553 -3,20% NEW BRUNSWICK MONCTON (WESTMORLAND CO.) TIMES-TRANSCRIPT MON-FRI 36 115 36 656 -1,48% NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN (ST. JOHN CO.) TELEGRAPH-JOURNAL MON-FRI 32 574 32 946 -1,13% QUEBEC CHICOUTIMI (LE FJORD-DU-SAGUENAY) LE QUOTIDIEN AVG (M-F) 26 635 26 996 -1,34% QUEBEC GRANBY (LA HAUTE-YAMASKA) LA VOIX DE L'EST MON-FRI 14 951 15 483 -3,44% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE -DE-MONTREAL)GAZETTE AVG (M-F) 147 668 143 782 2,70% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LE DEVOIR AVG (M-F) 26 099 26 181 -0,31% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LA PRESSE AVG (M-F) 198 306 200 049 -0,87% QUEBEC QUEBEC (COMMUNAUTE- URBAINE-DE-QUEBEC) LE SOLEIL AVG (M-F) 77 032 81 724 -5,74% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) LA TRIBUNE AVG (M-F) 31 617 32 006 -1,22% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) RECORD MON-FRI 4 367 4 539 -3,79% QUEBEC TROIS-RIVIERES (FRANCHEVILLE CEN. DIV. (MRC) LE NOUVELLISTE AVG (M-F) 41 976 41 886 0,21% ONTARIO OTTAWA CITIZEN AVG (M-F) 118 373 124 654 -5,04% ONTARIO OTTAWA-HULL LE DROIT AVG (M-F) 35 146 34 538 1,76% ONTARIO THUNDER BAY (THUNDER BAY DIST.) CHRONICLE-JOURNAL AVG (M-F) 25 495 26 112 -2,36% ONTARIO TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL AVG (M-F) 301 820 329 504 -8,40% ONTARIO TORONTO NATIONAL POST AVG (M-F) 150 884 190 187 -20,67% ONTARIO WINDSOR (ESSEX CO.) STAR AVG (M-F) 61 028 66 080 -7,65% MANITOBA BRANDON (CEN. -

Prescribed by Law/Une Règle De Droit©

PRESCRIBED BY LAW/UNE RÈGLE © DE DROIT ∗ ROBERT LECKEY In Multani, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Dans l’affaire Multani sur le port du kirpan, les kirpan case, judges disagree over the proper juges de la Cour suprême du Canada exprimèrent approach to reviewing administrative action under leur désaccord au sujet de l’approche adéquate au the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The contrôle des décisions administratives en vertu de la concurring judges questioned the leading judgment, Charte canadienne des droits et libertés. Les juges Slaight Communications, on the basis that it is minoritaires remirent en question l’arrêt Slaight inconsistent with the French text of section 1. This Communications, arguant que ce précédent était disagreement stimulates reflections on language and incompatible avec la version française de l’article culture in Canadian constitutional and administrative premier de la Charte. Ce désaccord soulève des law. A reading of both language versions of section 1, réflexions au sujet du rôle du langage et de la culture Slaight, and the critical scholarship reveals a au sein du droit constitutionnel et administratif linguistic dualism in which scholars read one version canadien. Une lecture des versions anglaise et of the Charter and of the judgment and write about française de l’article premier et de Slaight et de la them in that language. The separate streams doctrine revèle un dualisme linguistique par lequel undermine the idea of a shared, bilingual public law. les juristes lisent une seule version de la Charte et du Yet the differences exceed language. The article jugement et les commentent en cette même langue. -

Sherbrooke : Sa Place Dans La Vie De Relations Des Cantons De L’Est Pierre Cazalis

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:11 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Sherbrooke : sa place dans la vie de relations des Cantons de l’Est Pierre Cazalis Volume 8, numéro 16, 1964 Résumé de l'article Because they are due to economic contingencies rather than to unfavourable URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020498ar natural conditions, present-day regional disparities compel the geographer to DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/020498ar modify his concept of the region. Whereas in the past the region was considered essentially as a physical entity, to many authors it appears today to Aller au sommaire du numéro be « a functional area, based on communication and exchange, and as such defined less by its limits than by its centre » (Juillard). It is this concept which will be used in regional planning. Éditeur(s) Taking the city of Sherbrooke as a nodal centre, the author attempts to define such a region through an analysis and graphical representation of the Département de géographie de l'Université Laval complementary roles in influence and attraction played by the city in the fundamental aspects of employment, trade, finance, education, ISSN communication, health and government. Although it is already well-developed in the secondary sector, with more than 9,000 workers employed in industry 0007-9766 (imprimé) and an annual production worth more than $100 million, Sherbrooke bas a 1708-8968 (numérique) power of attraction and influence which is due essentially to its tertiary sector : wholesale trade, insurance, education, communication. Ac-cording to the Découvrir la revue criteria mentioned above, the area dominated by Sherbrooke includes the whole of the following counties : Sherbrooke, Stanstead, Richmond, Wolfe and Compton ; and the greater part of Frontenac, Mégantic, Artbabaska, Citer cet article Drummond and Brome counties. -

030140236.Pdf

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÈRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES QUÉBÉCOISES PAR CATHERINE LAMPRON-DESAULNIERS LA VIE CULTURELLE À TROIS-RIVIÈRES DANS LES ANNÉES 1960 : DÉMOCRATISA TI ON DE LA CUL TURE, DÉMOCRATIE CUL TU REL LE ET CUL TURE JEUNE. HISTOIRE D'UNE TRANSITION MARS 2010 Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Service de la bibliothèque Avertissement L’auteur de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse a autorisé l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières à diffuser, à des fins non lucratives, une copie de son mémoire ou de sa thèse. Cette diffusion n’entraîne pas une renonciation de la part de l’auteur à ses droits de propriété intellectuelle, incluant le droit d’auteur, sur ce mémoire ou cette thèse. Notamment, la reproduction ou la publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse requiert son autorisation. RÉSUMÉ L'objectif principal de cette recherche vise à mettre en lumière la transition culturelle qui s'effectue à Trois-Rivières au cours des années 1960. Le milieu culturel se transforme à plusieurs niveaux: les lieux de diffusion culturelle, les acteurs ainsi que la programmation culturelle en sont des exemples. L'analyse démontre tout le processus de démocratisation de la culture cultivée pris en charge par l'élite ainsi que l'émergence, à la fin de la décennie, de la démocratie culturelle mise de l'avant par une jeunesse qui sait s'imposer. Ces deux groupes ont su démontrer les caractéristiques dominantes de la diffusion de la culture cultivée dans une ville moyenne comme Trois-Rivières. -

Directors' Report to Shareholders

Directors’ Report to Shareholders The Power Corporation family of companies and investments had a very strong year in 2011, with stable results from the financial services businesses and a meaningful contribution from investing activities. While 2011 showed continued progress in global economic recovery, the year was nonetheless challenging. Interest rates were low and the economy and equity markets showed progress during the first half. This largely reversed itself during the second half of the year. Our results indicate that we have the risk-management culture, capital and liquidity to navigate these economic conditions successfully and that investment gains represent an attractive upside to our business. 2011 $499.6 $1,152 $574 BILLION MILLION MILLION CONSOLIDATED OPERATING DIVIDENDS ASSETS AND EARNINGS DECLARED ASSETS UNDER ATTRIBUTABLE TO MANAGEMENT PARTICIPATING SHAREHOLDERS Mission 13.0% $2.50 $1.16 Enhancing shareholder value RETURN ON OPERATING DIVIDENDS by actively managing operating EQUITY EARNINGS DECLARED BASED ON PER PER businesses and investments which OPERATING PARTICIPATING PARTICIPATING EARNINGS SHARE SHARE can generate long-term, sustainable growth in earnings and dividends. Value is best achieved through a prudent approach to risk and through responsible corporate citizenship. Power Corporation aims to act like an owner with a long-term perspective and a strategic vision anchored in strong core values. 6 POWER CORPORATION OF CANADA 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Power Corporation’s financial services companies are focused on providing protection, asset management, and retirement savings products and services. We continue to believe that the demographic trends affecting retirement savings, coupled with strong evidence that advice from a qualified financial advisor creates added value for our clients, reinforce the soundness of our strategy of building an advice-based multi-channel distribution platform in North America. -

The Day of Sir John Macdonald – a Chronicle of the First Prime Minister

.. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 29 THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD BY SIR JOSEPH POPE Part VIII The Growth of Nationality SIR JOHX LIACDONALD CROSSING L LALROLAILJ 3VER TIIE XEWLY COSSTRUC CANADI-IN P-ICIFIC RAILWAY, 1886 From a colour drawinrr bv C. \TT. Tefferv! THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD A Chronicle of the First Prime Minister of the Dominion BY SIR JOSEPH POPE K. C. M. G. TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1915 PREFATORY NOTE WITHINa short time will be celebrated the centenary of the birth of the great statesman who, half a century ago, laid the foundations and, for almost twenty years, guided the destinies of the Dominion of Canada. Nearly a like period has elapsed since the author's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald was published. That work, appearing as it did little more than three years after his death, was necessarily subject to many limitations and restrictions. As a connected story it did not profess to come down later than the year 1873, nor has the time yet arrived for its continuation and completion on the same lines. That task is probably reserved for other and freer hands than mine. At the same time, it seems desirable that, as Sir John Macdonald's centenary approaches, there should be available, in convenient form, a short r6sum6 of the salient features of his vii viii SIR JOHN MACDONALD career, which, without going deeply and at length into all the public questions of his time, should present a familiar account of the man and his work as a whole, as well as, in a lesser degree, of those with whom he was intimately associated. -

Yes, Your Tweet Could Be Considered Hate Speech,Ontario's

“Equitable Compensation” for a Breach of the Crown’s Fiduciary Duty Towards First Nations The Crown has a fiduciary relationship with Indigenous Peoples. What remedy do Indigenous Peoples have when the Crown breaches its fiduciary duty? The Supreme Court of Canada recently addressed this question in Southwind v Canada, which involved a breach that occurred nearly 100 years ago. In February 1928, the Governments of Canada, Ontario, and Manitoba entered into an agreement to dam Lac Seul in order to generate electricity for the growing city of Winnipeg.[1] The governments planned to raise the water level of Lac Seul by ten feet, which they knew would cause “very considerable” damage to the Lac Seul First Nation (LSFN), whose Reserve was — and still is — located on the southeastern shore of the lake.[2] When the dam was built, “[a]lmost one-fifth of [LSFN’s] best land was flooded and … [LSFN’s] members were deprived of their livelihood, robbed of their natural resources, and driven out of their homes.”[3] LSFN was not consulted on either the project itself,[4] or on the adequacy of the $50,000 compensation package that Canada and Ontario paid into the LSFN’s trust account in 1943.[5] As a general rule, the Crown owes a fiduciary duty towards an Indigenous group when it “assumes discretionary control over a specific Aboriginal interest.”[6] The Crown breached its duty in the Lac Seul dam project.[7] In this case, the remedy for the breach was “equitable compensation,” which the trial judge calculated according to what the Crown would have owed the LSFN under the laws of expropriation in 1929, when the breach occurred.[8] Mr Southwind, who was acting on behalf of the members of the LSFN, disagreed with this calculation and argued that the trial judge failed to consider the doctrine of equitable compensation in light of the constitutional principles of the honour of the Crown and reconciliation.[9] On July 16th, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled on Mr Southwind’s appeal. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982.