Drewreview V11.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1961 Climbers Outing in the Icefield Range of the St

the Mountaineer 1962 Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. Clubroom is at 523 Pike Street in Seattle. Subscription price is $3.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of Northwest America; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfillment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor Zif e. EDITORIAL STAFF Nancy Miller, Editor, Marjorie Wilson, Betty Manning, Winifred Coleman The Mountaineers OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES Robert N. Latz, President Peggy Lawton, Secretary Arthur Bratsberg, Vice-President Edward H. Murray, Treasurer A. L. Crittenden Frank Fickeisen Peggy Lawton John Klos William Marzolf Nancy Miller Morris Moen Roy A. Snider Ira Spring Leon Uziel E. A. Robinson (Ex-Officio) James Geniesse (Everett) J. D. Cockrell (Tacoma) James Pennington (Jr. Representative) OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES : TACOMA BRANCH Nels Bjarke, Chairman Wilma Shannon, Treasurer Harry Connor, Vice Chairman Miles Johnson John Freeman (Ex-Officio) (Jr. Representative) Jack Gallagher James Henriot Edith Goodman George Munday Helen Sohlberg, Secretary OFFICERS: EVERETT BRANCH Jim Geniesse, Chairman Dorothy Philipp, Secretary Ralph Mackey, Treasurer COPYRIGHT 1962 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS The Mountaineer Climbing Code· A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. -

Short Film Programme

SHORT FILM PROGRAMME If you’d like to see some of the incredible short films produced in Canada, please check out our description of the Short Film Programme on page 50, and contact us for advice and assistance. IM Indigenous-made films (written, directed or produced by Indigenous artists) Films produced by the National Film Board of Canada NFB CLASSIC ANIMATIONS BEGONE DULL CARE LA FAIM / HUNGER THE STREET Norman McLaren, Evelyn Lambart Peter Foldès 1973 11 min. Caroline Leaf 1976 10 min. 1949 8 min. Rapidly dissolving images form a An award-winning adaptation of a An innovative experimental film satire of self-indulgence in a world story by Canadian author Mordecai consisting of abstract shapes and plagued by hunger. This Oscar- Richler about how families deal with colours shifting in sync with jazz nominated film was among the first older relatives, and the emotions COSMIC ZOOM music performed by the Oscar to use computer animation. surrounding a grandmother’s death. Peterson Trio. THE LOG DRIVER’S WALTZ THE SWEATER THE BIG SNIT John Weldon 1979 3 min. Sheldon Cohen 1980 10 min. Richard Condie 1985 10 min. The McGarrigle sisters sing along to Iconic author Roch Carrier narrates A wonderfully wacky look at two the tale of a young girl who loves to a mortifying boyhood experience conflicts — global nuclear war and a dance and chooses to marry a log in this animated adaptation of his domestic quarrel — and how each is driver over more well-to-do suitors. beloved book The Hockey Sweater. resolved. Nominated for an Oscar. -

Annual Report 2010-2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2010-2011 HEAD OFFICE P.O. BOX 2398 UNIT 111-EIGHT STOREY 8 ASTRO HILL IQALUIT, NUNAVUT, CANADA The Nunavut Film Development Corporation (NFDC) is a non-governmental organization, established by the Government of Nunavut to provide training and funding though various programs for the production and marketing of film, television and digital media. In meeting its mandate, NFDC's vision is to position Nunavut as a competitive, circumpolar production centre, where Nunavummiut and guests can create quality production that is marketed and distributed to both the domestic and global market. Our policies and programs reflect the six guiding principles of Inuit Quajimajatuqangit. OUR MANDATE The mandate of the Nunavut Film Development Corporation is to increase economic and artistic opportunities for Nunavummiut in the film television and digital media industries and to promote Nunavut as a world-class circumpolar production centre. CORE RESPONSIBILITIES The Nunavut Film Development Corporation embraces and accepts that it is responsible to: Ensure that all activities undertaken by to organization will be carried out under the principals of Inuit Quajimajatuqangit (IQ) Work with the community to sustain and grow a competitive Nunavut owned and controlled film, television and digital media industry. Enable Nunavut production companies to foster existing relationships and to equip same with the tools and resources necessary to establish new relationships with national and international co-financing partners. Assist and enhance the ability of the Nunavut film, television and digital media industry to secure development, production, distribution and marketing financing. To utilize best management practices to administer territorial funding programs in an open, equitable and effective manner. -

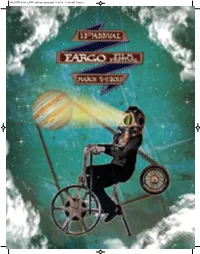

FFF 2004 Program.Qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 1 2013 FFF8.5X11 Fff2004program.Qxd2/20/1311:18Ampage2 1

2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 1 2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 2 DAN FRANCIS PHOTOGRAPHY 1 2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 3 ONCE UPON A TIME, MOTION PICTURES WERE ENORMOUS THINGS. Massive amounts of 35mm film were packed neatly in unwieldy padlocked metal cans and sent to a world’s worth of neighborhood cinemas. During my tenure at a local multiplex, a particularly long movie about a boy wizard resulted in a particularly massive film print. I managed to get this print halfway up a particularly steep staircase before tumbling bow-tie first down to what I feared was my doom but was, in fact, a conveniently placed pile of industrial sized bags of Orville Redenbacher. After that, I left it to our fearless projectionists to struggle them up the stairs to dimly lit projection booths. There, hunched over miles of celluloid, they would work into the wee hours of the morning – steady hands and bleary eyes assembling a new adventure. Such was the weight of storytelling. And the enormity of it made sense to me. Should one be able to lose the life and times of Charles Foster Kane if it slides down into that little space between the entertainment center and the wall? Emily Beck FARGO THEATRE Should the battle against an evil galactic empire be shipped in a standard packing envelope lined with those delicious little bubbles? Executive Director Isn’t it only fitting that the epic journey to return The One Ring (back to the fiery chasm from whence it came) be so enormous it could topple a teenager in an usher’s tuxedo made entirely of polyester? But the world turned. -

New Arrivals August 2020

EMMA STEWART RESOURCES CENTRE New Arrivals August 2020 Emma Stewart Resources Centre Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation Mail: 2317 Arlington Avenue, Saskatoon, SK S7J 2H8 Office: Arbos Centre for Learning, 2311 Arlington Ave, Saskatoon, SK Telephone: 306-373-1660 Email: [email protected] Please note: Annotations have been excerpted and/or adapted from descriptions provided by the publishers. 004.678083 K15 Kamenetz, Anya The art of screen time : how your family can balance digital media and real life New York, NY : Public Affairs, 2018. Subjects: Families. Information technology—Social aspects. Internet addiction. Internet and children. Internet and families. Summary: Many have been quick to declare this the dawn of a neurological and emotional crisis, but solid science on the subject is surprisingly hard to come by. In this book, the author takes a refreshingly practical look at the subject. Surveying hundreds of fellow parents on their practices and ideas, and cutting through a thicket of inconclusive studies and overblown claims, she hones a simple message, a riff on Michael Pollan's well-known "food rules": Enjoy Screens. Not too much. Mostly with others. 026.7415 P574 Phoenix, Jack Maximizing the impact of comics in your library : graphic novels, manga, and more Santa Barbara, CA : Libraries Unlimited, 2020. Subjects: Libraries—Activity programs. Libraries—Special collections—Comic books, strips, etc. Libraries—Special collections—Graphic novels. Summary: This unique guide offers fresh insights on how graphic novels and comics differ from traditional books and require different treatment in the library, from purchasing, shelving, and cataloging to readers' advisory services, programs, and curriculum. 027.625 T459 Thomas, Nancy Pickering; Crow, Sherry R. -

A City out of Old Songs

A City Out of Old Songs: The influence of ballads, hymns and children’s songs on an Irish writer and broadcaster Catherine Ann Cullen Context Statement for PhD by Public Works Middlesex University Director of Studies: Dr Maggie Butt Co-Supervisor: Dr Lorna Gibb Contents: Public Works Presented as Part 1 of this PhD ............................................................ iii List of Illustrations ....................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... v Preface: Come, Gather Round ..................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Singing Without Ceasing .................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: A Tune That Could Calm Any Storm ......................................................... 23 Chapter 3: Something Rich and Strange .................................................................... 47 Chapter 4: We Weave a Song Beneath Our Skins ...................................................... 66 Chapter 5: To Hear the Nightingale Sing ................................................................... 98 Conclusion: All Past Reflections Shimmer into One ............................................... 108 Works Cited .............................................................................................................. 112 Appendix 1: Index of Ballads and Songs used -

April 2001 J 0 Urnal

A forum for Christian school educators Christian Educators Volume 40 No. 4 April 2001 J 0 urnal When t:vetJJtltiufl Is a SOHfl Editorial My sister-in-law's mother died Why Do We Sing? my boss in a church in the Neth of Alzheimer's disease several erlands. He could sing really years ago. To wards the end of her mother's life, communica well, and he knew it too. I sat next to him doing my best. After tion was almost non-existent, except when my sister-in-law church he said to me, 'The way you sing, you may as well keep would sing songs her mother had learned earlier in life, espe your mouth shut.' That really happened to me, and it hurt. It cially psalms and hymns. These songs elicited a response where took me a long time to get over that. Why do we sing anyway? otherwise eyes remained blank, and mouth still. Babies notice When I was young, I used to sing when no one heard me, and ably respond to singing, and children love to engage in it. One then I could sing to my heart's content." The man's voice broke might conclude from this and many other examples that sing when he told me this, and his eyes filled with tears at the pain ing is very basic to our existence. It seems to go to and come ful memory of that insensitive and arrogant remark. He has from the core of our being. since departed this world and may well be giving singing les But something happens to most children on their way to sons to his former boss in heaven, provided the man has soft adulthood. -

The Film Festival Fills the Ballroom

The WEDNESDAY, APRIL 18, 2012 • VOL. 24, NO. 25 $1.25 Edmunston, N.B. won the Live Right Now contest, but didn't we have KLONDIKE fun trying? SUN The Film Festival Fills the Ballroom There were lots of bottoms on seats at the annual short film festival. See story on page 5. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue Muesum flooding 3 Ducks Unlimited 6 River Breakup Stats 9 Come check out Artifacts were damaged but prompt The auction is a great success for Stephen Johnson predicts Breakup action was crucial in preventing the organization and the town. with better odds than Lotto 649. our great selection more problems. of sale books! See & Do in Dawson 2 Yukon Queen II gone 8 DCA AGM 16 The Cookshack (NEW!) 20 Uffish Thoughts 4 TV Guide 10-14 HACES Graduation 18 Kids' Corner 22 Larry Hil on Berton House 7 Fast Track Mining Report 15 AN Irish Nugget 19 City of Dawson 24 P2 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 18, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to Get the Rec & Leisure Newsletter & stay up to date. Website: www. cityofdawson.ca. Facebook: "City of Dawson Recreation". Contact us at SEE AND DO 993-2353.The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to in DAWSON now: close. More live entertainment in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 p.m.The toDowntown 8:30 p.m. Hotel LIVE MusIC - : Barnacle Bob is now playing in the Sourdough Saloon ev This free public service helps our readers find their way through CRIBBAGE TOURNAMENTS the many activities all over town. -

Voice in the Poetry of Selected Native American

SPEAKING THROUGH THE SILENCE: VOICE IN THE POETRY OF SELECTED NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN POETS by D’JUANA ANN MONTGOMERY Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON MAY 2009 Copyright © by D’Juana Ann Montgomery 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Knowing where to actually begin in acknowledging all of those who have helped make completing this process possible is daunting—there are so many who have contributed in so many ways. Dr. Kenneth Roemer, my dissertation chair, has been an invaluable source of guidance and encouragement throughout the course of my doctoral work. Dr. Tim Morris and Dr. Laurin Porter have also been invaluable in helping me complete the final drafts of this project. I must also acknowledge my English Department colleagues Diane Lewis, Dessita Rury, and Dr. Amy Alexander at Southwestern Assemblies of God University. These wonderful friends have been a continual source of strength and encouragement and have seemingly never tired of listening to me talk about the ups and downs of my project. My heartfelt thanks also goes to Kathy Hilbert, my good friend and colleague from Hill College who has read the drafts of my chapters almost as many times as I have. Finally, and perhaps, most importantly, I must acknowledge the support and sacrifices of my family. My husband Max has always been my biggest supporter; he has never failed to encourage and support me in any way possible. -

The Second Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Second Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Second Jungle Book Author: Rudyard Kipling Release Date: September 21, 2008 [EBook #1937] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK *** Produced by An Anonymous Volunteer, and David Widger THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK By Rudyard Kipling Contents HOW FEAR CAME THE LAW OF THE JUNGLE THE MIRACLE OF PURUN BHAGAT A SONG OF KABIR LETTING IN THE JUNGLE MOWGLI'S SONG AGAINST PEOPLE THE UNDERTAKERS A RIPPLE SONG THE KING'S ANKUS THE SONG OF THE LITTLE HUNTER QUIQUERN 'ANGUTIVAUN TAINA' RED DOG CHIL'S SONG THE SPRING RUNNING THE OUTSONG HOW FEAR CAME The stream is shrunk—the pool is dry, And we be comrades, thou and I; With fevered jowl and dusty flank Each jostling each along the bank; And by one drouthy fear made still, Forgoing thought of quest or kill. Now 'neath his dam the fawn may see, The lean Pack-wolf as cowed as he, And the tall buck, unflinching, note The fangs that tore his father's throat. The pools are shrunk—the streams are dry, And we be playmates, thou and I, Till yonder cloud—Good Hunting!—loose The rain that breaks our Water Truce. -

3-6 Oct . 2019 Montréal

3-6 OCT. 2019 MONTRÉAL 2 21st Inuit Studies Conference 21e Congrès d’Études Inuit October 3rd–6th, 2019 | du 3 au 6 octobre 2019 Université du Québec à Montréal Montréal, Québec, Canada Final Programme | Programme définitive (October 3, 2019 3 octobre 2019) 2 3 General Information | Informations générales PDF Version of Programme | Version PDF du programme Additional information can be found on the Des informations supplémentaires se trou- conference website. vent sur le site Web du congrès. Conference Logo | Logo du congrès The conference logo was designed by Le logo du congrès a été conçu par le graphic artist/designer Thomassie Mangiok: graphiste et designer Thomassie Mangiok : https://twitter.com/mangiok/. Check out https://twitter.com/mangiok/. Décou- his new board game, Nunami: https://www. vrez son nouveau jeu de société, Nunami : kickstarter.com/projects/nunamigame/ https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/ nunami-an-inuit-game nunamigame/nunami-an-inuit-game Digital Version | Version numérique An interactive version of the schedule is Une version interactive de lʼhoraire est available online and on the Grenadine Event disponible en ligne, ainsi quʼavec lʼappli Guide app (App Store and Google Play), us- «Grenadine Event Guide» (App Store et ing the code ISC2019. Google Play), en utilisant le code ISC2019. Smart Phone App | Appli pour téléphone intelligente Vous pouvez télécharger et obtenir des Vous pouvez télécharger et receveoir ver- mises à jour sur la conférence à lʼaide sion interactive de lʼhoraire est disponible en de lʼapplication pour smartphone Grenadine ligne, ainsi quʼavec lʼappli «Grenadine Event Event Guide (App Store et Google Play), en Guide» (App Store et Google Play), en utilisant saisissant le code ISC2019. -

Associate Professor in Art and Music Honors Adviser

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC HEARING VOICES IN SHOSTAKOVICH UNCOVERING HIDDEN MEANINGS IN THE FILM ODNA CAROLE CHRISTIANA SMITH Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Music with honors in Music Reviewed and approved* by the following: Eric J. McKee Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Charles D. Youmans Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Mark E. Ballora Associate Professor in Art and Music Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT While the concert works of Dmitri Shostakovich have been subject to much research and analysis by scholars, his works for film remain largely unknown and unappreciated. Unfortunately so, since Shostakovich was involved with many of the projects that are hallmarks of Soviet Cinema or that changed the course of the country‘s cinematic development. One such project, the film Odna (1931), was among the first sound films produced in the Soviet Union and exhibits the innovative methods of combining sound and image in order enhance to audience‘s understanding of the films message. This thesis will examine the use and representation of the human voice in the sound track of Odna and how its interaction with the visual track produces deeper levels of meaning. In designing the sound track, Shostakovich employs the voice in several contexts: recorded dialogue, songs, and vocal ―representations‖ whereby music mimics speech. These vocal elements will be examined through theoretical analysis in the case of music, and dramatic importance in the case of dialogue and sound effects.