A City out of Old Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Patrick Street Patrick Street Mp3, Flac, Wma

Patrick Street Patrick Street mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Patrick Street Country: US Released: 1988 Style: Folk, Celtic MP3 version RAR size: 1260 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1266 mb WMA version RAR size: 1193 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 736 Other Formats: MIDI AA MMF VOC APE TTA AAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Patrick Street / The Carraroe Jig 2 Walter Sammon's Grandmother / Concertina Reel / Brenda McMahon's The Holy Ground 3 Written-By – Gerry O'Beirne 4 The Shores Of Lough Gowna / Contentment Is Wealth / Have A Drink With Me 5 French Canadian Set "La Cardeuse" 6 Loftus Jones The Dream 7a Written By – Andy Irvine Indiana 7b Written-By – Andy Mitchell 8 Martin Rochford's Reel / Roll Out The Barrel / The Earl's Chair 9 Mrs. O'Sullivan's Jig / Caliope House The Man With The Cap 10 Written-By – Colum Sands Credits Accordion – Jackie Daly Engineer, Producer – Donal Lunny Fiddle – Kevin Burke Guitar – Arty McGlynn Keyboards, Bodhrán – Donal Lunny Photography By – Colm Henry Vocals, Bouzouki, Mandolin, Harmonica – Andy Irvine Notes Lyrics included. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 048248107129 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Green SIF 1071 Patrick Street Patrick Street (LP, Album) SIF 1071 US 1987 Linnet Kevin Burke , Kevin Burke , Jackie Daly, Jackie Daly, Andy Green CSIF 1071 Andy Irvine, Arty McGlynn CSIF 1071 Ireland 1987 Irvine, Arty Linnet - Patrick Street (Cass) McGlynn Green SIF 1071 Patrick Street Patrick Street (LP, Album) SIF 1071 Ireland 1987 Linnet Green GLCD 1071 Patrick Street Patrick Street (CD, Album) GLCD 1071 US 1988 Linnet Related Music albums to Patrick Street by Patrick Street Capercaillie - Dusk Till Dawn - The Best Of Capercaillie Andy Irvine & Donal Lunny's Mozaik - Changing Trains Patrick Street - No. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

A Farewell to Alms

A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World Draft, 1 October 2006 Forthcoming, Princeton University Press, 2007 He is a benefactor of mankind who contracts the great rules of life into short sentences, that may be easily impressed on the memory, and so recur habitually to the mind --Samuel Johnson Gregory Clark University of California Davis, CA 95616 ([email protected]) 1. Introduction…………………………………….. 1-13 The Malthusian Trap: Economic Life to 1800 2. The Logic of the Malthusian Economy…………. 15-39 3. Material Living Standards……………………….. 40-76 4. Fertility………………………………………….. 78-99 5. Mortality………………………………………… 100-131 6. Malthus and Darwin: Survival of the Richest……. 132-152 7. Technological Advance…………………………..153-179 8. Preference Changes………………………………180-207 The Industrial Revolution 9. Modern Growth: the Wealth of Nations………… 208-227 10. The Problem of the Industrial Revolution……….. 228-256 11. The Industrial Revolution in Britain, 1760-1860…. 257-293 12 Social Consequences of the Industrial Revolution.. 294-330 The Great Divergence 13. The Great Divergence: World Growth since 1800.. 331-364 14. The Proximate Sources of Divergence…………... 365-394 15. Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?.................. 395-420 16. Conclusion: Strange New World………………… 421-422 Technical Appendix……………………………... 423-427 References……………………………………….. 428-451 ii 1 Introduction The basic outline of world economic history is surprisingly simple. Indeed it can be summarized in one diagram: figure 1.1. Before 1800 income per person – the food, clothing, heat, light, housing, and furnishings available per head - varied across socie- ties and epochs. But there was no upward trend. A simple but powerful mechanism explained in this book, the Malthusian Trap, kept incomes within a range narrow by modern standards. -

33 UCLA L. Rev. 379 December, 1985

UCLA LAW REVIEW 33 UCLA L. Rev. 379 December, 1985 RULES AND STANDARDS Pierre J. Schlag a1 © 1985 by the Regents of the University of California; Pierre J. Schlag INTRODUCTION Every student of law has at some point encountered the “bright line rule” and the “flexible standard.” In one torts casebook, for instance, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Benjamin Cardozo find themselves on opposite sides of a railroad crossing dispute.1 They disagree about what standard of conduct should define the obligations of a driver who comes to an unguarded railroad crossing. Holmes offers a rule: The driver must stop and look.2 Cardozo rejects the rule and instead offers a standard: The driver must act with reasonable caution.3 Which is the preferable approach? Holmes suggests that the requirements of due care at railroad crossings are clear and, therefore, it is appropriate to crystallize these obligations into a simple rule of law.4 Cardozo counters with scenarios in which it would be neither wise nor prudent for a driver to stop and look.5 Holmes might well have answered that Cardozo’s scenarios are exceptions and that exceptions prove the rule. Indeed, Holmes might have parried by suggesting that the definition of a standard of conduct by means of a legal rule is predictable and certain, whereas standards and juries are not. This dispute could go on for quite some time. But let’s leave the substance of this dispute behind and consider some observations about its form. First, disputes that pit a rule against a standard are extremely common in legal discourse. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

December 2016

Traditional Folk Song Circle goers to hear Potomac Accordion Ensemble December 10 December 2016 Inside this issue: From the President 2 Open Mics 3 Pics from Sunday Open Stage 4 Traditional Folk Song Circle 5 The Songs We Sing 6 Comfortable Concerts 7 Hill Chapel Concert 9 Gear of the Month 10 Pull up a Chair 12 Other Music Orgs of interest 13 Member Ads 14 Open Mic Photos 16 Board of Directors 18 F.A.M.E. Goals 18 Membership Renewal/App 18 Poster art courtesy of Todd C Walker Page 2 From the President I don’t know whose thought this is, but I read somewhere that “music is the wheels of a movement. I know that music made a tremendous difference in the anti- war movement of the 60s as well as the civil rights movement. Music is a powerful force that is often unrecognized. A song has a way of inspiring folks that nothing else comes even close to. We are in need of inspiring songs. One of the roles of a songwriter is not only to reflect on what is happening in the present but also to provide a vision of the future. What is your vision of the future? For some it is nihilistic bleakness – a very cynical response to our world. For others, it is filled with hope – we are somehow going to be able to figure out how we can live together and with all of creation. If you are a performer, I want to challenge you to get out of yourself and add songs that reflect your vision of the future to your repertoire. -

Everything Useful I Know About Real Life I Know from Movies. Through An

Young adult fiction www.peachtree-online.com Everything useful I know about real ISBN 978-1-56145-742-7 $ life I know from movies. Through an 16.95 intense study of the characters who live and those that die gruesomely in final Sam Kinnison is a geek, and he’s totally fine scenes, I have narrowed down three basic with that. He has his horror movies, approaches to dealing with the world: his nerdy friends, and World of Warcraft. Until Princess Leia turns up in his 1. Keep your head down and your face out bedroom, worry about girls he will not. of anyone’s line of fire. studied cinema and Then Sam meets Camilla. She’s beautiful, MELISSA KEIL 2. Charge headfirst into the fray and friendly, and completely irrelevant to anthropology and has spent time as hope the enemy is too confused to his life. Sam is determined to ignore her, a high school teacher, Middle-Eastern aim straight. except that Camilla has a life of her own— tour guide, waitress, and IT help-desk and she’s decided that he’s going to be a person. She now works as a children’s 3. Cry and hide in the toilets. part of it. book editor, and spends her free time watching YouTube and geek TV. She lives Sam believes that everything he needs to in Australia. know he can learn from the movies…but “Sly, hilarious, and romantic. www.melissakeil.com now it looks like he’s been watching the A love story for weirdos wrong ones. -

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine Remember Planxty Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com 1 [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 Biographie Icônes de la musique irlandaise des années 70, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine proposent un hommage au groupe Planxty, véritable référence de la musique folk irlandaise connue du grand public. Producteurs, managers, leaders de groupes d’anthologie de la musique irlandaise comme Sweeney’s Men , Planxty, The Bothy Band, Mozaik, LAPD et récemment Usher’s Island, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine ont développé à travers les années un style musical unique qui a rendue populaire la musique irlandaise traditionnelle. Andy Irvine est un musicien traditionnel irlandais chanteur et multi-instrumentiste (mandoline, bouzouki, mandole, harmonica et vielle à roue). Il est également l’un des fondateurs de Planxty. Après un voyage dans les Balkans, dans les années 70 il assemble différentes influences musicales qui auront un impact majeur sur la musique irlandaise contemporaine. Dònal Lunny est un musicien traditionnel irlandais, guitariste, bouzoukiste et joueur de bodhrán. Depuis plus de quarante ans, il est à l’avant-garde de la renaissance de la musique traditionnelle irlandaise. Depuis les années 80, il diversifie sa palette d’instruments en apprenant le clavier, la mandoline et devient producteur de musique, l’amenant à travailler avec entre autres Paul Brady, Rod Stewart, Indigo Girls, Sinéad O’Connor, Clannad et Baaba Maal. Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 2 Line Up Andy Irvine : voix, mandoline, harmonica Dònal Lunny : voix, bouzouki, bodhran Paddy Glackin : fiddle Discographie Andy Irvine - 70th Birthday Planxty - A retrospective Concert at Vicar St. -

May 26, 2016 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE MICHIGAN IRISH

May 26, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MICHIGAN IRISH MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2016 LINEUP 4-Day Festival Returns Sept. 15 - 18 The Michigan Irish Music Festival will kick off the 2016 festival with a Pub Preview Party again on Thursday night. The Pub Party will give patrons a preview of the weekend with food, beverage, and entertainment in the pub tent only. Entry is only $5 (cash only Thursday). Three bands will play Thursday. The full festival opens Friday with all five stages and the complete compliment of food, beverages (domestic beer, Irish whiskey, Irish cider and local craft beer), shopping and cultural/dance offerings. The music line-up is being finalized with over 20 bands on tap. Altan – The seeds of Altan lie in the music and spontaneity of sessions in kitchens and pubs in their hometown of Donegal, where their music was heard in an atmosphere of respect and intimacy. It is here that the band's heart still lies, whether they are performing on TV in Australia or jamming with Ricky Skaggs on the west coast of the United States. Andy Irvine – Andy Irvine is one of the great Irish singers, his voice one of a handful of truly great ones that gets to the very soul of Ireland. He has been hailed as "a tradition in himself." Musician, singer and songwriter, Andy has maintained his highly individual performing skills throughout his 45-year career. A festival favorite, Scythian, returns. Named after Ukrainian nomads, Scythian (sith-ee-yin) plays immigrant rock with thunderous energy, technical prowess, and storytelling songwriting, beckoning crowds into a barn-dance rock concert experience. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

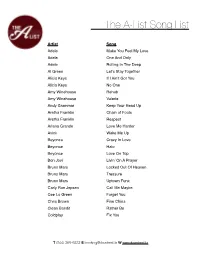

The A-List Songlist 2015

The A-List Song List Artist Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Adele One And Only Adele Rolling In The Deep Al Green Let’s Stay Together Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys No One Amy Winehouse Rehab Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammar Keep Your Head Up Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Respect Ariana Grande Love Me Harder Avicii Wake Me Up Beyonce Crazy In Love Beyonce Halo Beyonce Love On Top Bon Jovi Livin’ On A Prayer Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Cee Lo Green Forget You Chris Brown Fine China Clean Bandit Rather Be Coldplay Fix You T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song Coldplay Viva La Vida Corinne Bailey Rae Put You Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Daft Punk Lose Yourself To Dance David Guetta Ft. Sia Titanium Destiny’s Child Say My Name Earth, Wind, and Fire Let’s Groove Earth, Wind, And Fire September Ed Sheeren Thinking Out Loud Ellie Golding Love Me Like You Do Ellie Golding Need Your Love Emeli Sande Next To Me Estelle American Boy Etta James At Last Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Frank Valli December ’63 (Oh What A Night) Gnarls Barkley Crazy Guns ‘N’ Roses Sweet Child Of Mine Jackson 5 ABC Jackson 5 I Want You Back Jason Mraz I’m Yours Jay Z & Alicia Keys Empire State Of Mind Jazz Standard Summertime Jessie J Domino John Legend All Of Me T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song John Legend Ordinary People Journey Crazy Little Thing Called Love Journey Don’t Stop Believin Justin Timberlake Señorita Justin Timberlake Sexyback Justin Timberlake Suit & Tie Katy Perry California Girls Katy Perry Firework Katy Perry Roar Katy Perry Teenage Dream Kenny Loggins Footloose Lady Gaga Just Dance Lorde Royals Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Sugar Maroon 5 Sunday Morning Marvin Gaye What’s Going On Marvin Gaye Ft.