RACE, GENDER and VIOLENCE on the TRANSATLANTIC EXTREME-RIGHT, 1969-2009 a Dissertation Presented by Simon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Measurement Study of Genetic Testing Conversations on Reddit and 4Chan

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) “And We Will Fight for Our Race!” A Measurement Study of Genetic Testing Conversations on Reddit and 4chan Alexandros Mittos, Savvas Zannettou,† Jeremy Blackburn,‡ Emiliano De Cristofaro University College London, †Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, ‡Binghamton University {a.mittos, e.decristofaro}@ucl.ac.uk, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Alas, increased popularity of self-administered genetic tests has also been accompanied by media reports of far-right Progress in genomics has enabled the emergence of a boom- ing market for “direct-to-consumer” genetic testing. Nowa- groups using it to attack minorities or prove their genetic days, companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA provide af- “purity” (Reeve 2016), mirroring concerns of a new wave of fordable health, genealogy, and ancestry reports, and have al- scientific racism (Reich 2018). Also, statements from Don- ready tested tens of millions of customers. At the same time, ald Trump led Senator Warren to publicly confirm her Native alt- and far-right groups have also taken an interest in genetic American ancestry via genetic testing (Linskey 2018). testing, using them to attack minorities and prove their ge- Interest in DTC genetic testing by right-wing communi- netic “purity.” In this paper, we present a measurement study ties comes at a time when racism, hate, and antisemitism on shedding light on how genetic testing is being discussed on platforms like 4chan, Gab, and certain communities on Red- Web communities in Reddit and 4chan. We collect 1.3M comments posted over 27 months on the two platforms, us- dit is on the rise (Hine et al. -

What Is Gab? a Bastion of Free Speech Or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?

What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber? Savvas Zannettou Barry Bradlyn Emiliano De Cristofaro Cyprus University of Technology Princeton Center for Theoretical Science University College London [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Haewoon Kwak Michael Sirivianos Gianluca Stringhini Qatar Computing Research Institute Cyprus University of Technology University College London & Hamad Bin Khalifa University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn University of Alabama at Birmingham [email protected] ABSTRACT ACM Reference Format: Over the past few years, a number of new “fringe” communities, Savvas Zannettou, Barry Bradlyn, Emiliano De Cristofaro, Haewoon Kwak, like 4chan or certain subreddits, have gained traction on the Web Michael Sirivianos, Gianluca Stringhini, and Jeremy Blackburn. 2018. What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?. In WWW at a rapid pace. However, more often than not, little is known about ’18 Companion: The 2018 Web Conference Companion, April 23–27, 2018, Lyon, how they evolve or what kind of activities they attract, despite France. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3184558. recent research has shown that they influence how false informa- 3191531 tion reaches mainstream communities. This motivates the need to monitor these communities and analyze their impact on the Web’s information ecosystem. 1 INTRODUCTION In August 2016, a new social network called Gab was created The Web’s information ecosystem is composed of multiple com- as an alternative to Twitter. -

Gerr"1AN IDENT ITV TRANSFORNED

GERr"1AN IDENT ITV TRANSFORNED 1. Is GePmany a SpeciaZ Case? German identity problems are usually viewed as a special case. I do not think it is necessary to argue this point with any elabor ation. It is argued that the Germans' obsessions about identity reached a peak of mental aberration in the Second World War, when in a fit of total national insanity they set about mass murdering most of Europe on the grounds of arbitrary and invented grades of approved and disapproved races, drawn from a misunderstanding of physical anthropology. The sources of the identity problem have been subjected to a great deal of analysis, but remain obscure. l Before I go on to look at how true it is that German identity poses special problems, let me briefly mention a recent example of the extent to which the attitudes drawn from the Second World War have permeated our consciousness. I enjoy science fiction, and last summer I watched a film on TV, made in America by a consortium of apparently largely Mafia money, which concerned the invasion of the earth from outer space. The invaders were lizards from another solar system. They were lizards who were able to make themselves look like people by wearing a synthetic human skin, but underneath were reptiles. Some clever people observed this from the beginning, but were disbelieved. The lizards seemed friendly, and quickly acquired what were called collaborators, drawn from the ambitious and weak elements in society. Lizards played on conservative instincts, such as a desire for law and order. -

Alwin Seifert and Nazi Environmentalism

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 5-2020 Advocates for the Landscape: Alwin Seifert and Nazi Environmentalism Peter Staudenmaier Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/hist_fac Part of the History Commons Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications/College of Arts and Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. German Studies Review, Vol. 43, No. 2 (May 2020): 271-290. DOI. This article is © Johns Hopkins University Press and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. Johns Hopkins University Press does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Johns Hopkins University Press. Advocates for the Landscape: Alwin Seifert and Nazi Environmentalism Peter Staudenmaier ABSTRACT Reexamining debates on ostensibly green facets of Nazism, this article offers a case study of the "landscape advocates" led by Alwin Seifert from 1934 to 1945. In contrast to previous accounts focused on the role of the landscape advocates in the construction of the Autobahn, the article assesses their work on a wide range of projects in Nazi Germany and across occupied Europe. It argues that existing scholarship has not fully recognized the extent of the landscape advocates' involvement in Nazi structures and has sometimes misunderstood the relationship between their environmental activities and blood and soil ideology. Seven decades after the defeat of Hitler's dictatorship, the European landscape still bears the scars of war and genocide. -

How CREEP Hired Nazis for Nixon's Calif

JUNE 22, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37 /NUMBER- 24 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE -page 6 Dean spills beans: ·~. exposes dozens ·~ .· of 'dirty trick~' How CREEP hired Nazis for Nixon's Calif. campaig~ · The Nixon-Brezhnev summit--meaning of international detente -page 3 In Brief STUDENTS REPUDIATE NIXON'S COTERIE: Students St. Cloud State College, and Anoka-Ramsey Junior Col launched protest actions against friends of Nixon on lege, among others. several campuses recently. He explained how the agreement ending the occupa Attorney General Elliot Richardson decided that discre tion of Wounded Knee had resolved none of the major THIS tion is sometimes the better part of valor and cancelled issues. He predicted continued actions demanding the re a commencement address at Georgetown University after mov al of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from the Pine WEEK'S threatened with a massive boycott Ridge Reservation, and enforcement of the 1868 treaty. At Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minn., stu Bellecourt told how supporters of the occupation on MILITANT dents, faculty, and alumni signed a petition repudiating the reservation have been harassed and threatened since the honorary degree awarded to W atergater Maurice Stans the agreement was signed. 5 Move to silence W'gate back in 1970. Six hundred dollars was raised on the tour for the hearings blocked The petition pointed out that even discounting his most legal defense of those victimized for the occupation, but 7 Judge orders disclosure recent criminal dealings, there was "no adequate justifi funds are still needed. Contributions can be sent to: of illegal gov't spying cation for the belief that Mr. -

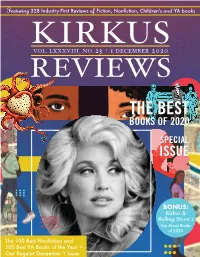

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

Pursuit of an Ethnostate: Political Culture and Violence 22 in the Pacific Northwest Joseph Stabile

GEORGETOWN SECURITY STUDIES REVIEW Published by the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service Editorial Board Rebekah H. Kennel, Editor-in-Chief Samuel Seitz, Deputy Editor Stephanie Harris, Associate Editor for Africa Kelley Shaw, Associate Editor for the Americas Brigitta Schuchert, Associate Editor for Indo-Pacific Daniel Cebul, Associate Editor for Europe Simone Bak, Associate Editor for the Middle East Eric Altamura, Associate Editor for National Security & the Military Timothy Cook, Associate Editor for South and Central Asia Max Freeman, Associate Editor for Technology & Cyber Security Stan Sundel, Associate Editor for Terrorism & Counterterrorism The Georgetown Security Studies Review is the official academic journal of Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program. Founded in 2012, the GSSR has also served as the official publication of the Center for Security Studies and publishes regular columns in its online Forum and occasional special edition reports. Access the Georgetown Security Studies Review online at http://gssr.georgetown.edu Connect on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/GeorgetownUniversityGSSR Follow the Georgetown Security Studies Review on Twitter at ‘@gssreview’ Contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] Table of Contents Understanding Turkey’s National Security Priorities in Syria 6 Patrick Hoover Pursuit of an Ethnostate: Political Culture and Violence 22 in the Pacific Northwest Joseph Stabile Learn to Live With It: The Necessary, But Insufficient, -

White Lies: the Empty Signifier in White Supremacy and the Alt.Right

Chris Knight WHITE LIES: THE EMPTY SIGNIFIER IN WHITE SUPREMACY AND THE ALT.RIGHT The Phenomenology of Whiteness: A Genealogy e begin in darkness. The narrative of whiteness begins in a void, an Wabsence, and myth. In many creation myths, including Genesis and Hesiod’s Theogony, order is wrested from undifferentiated chaos and dark- ness, and order is imposed by a divine enlightenment, a god/monarch who creates light by fiat. “In the beginning . the earth was without form and void and darkness was on the face of the deep.” And by creating light, the god/monarch gives meaning and hierarchy to the world. Whiteness, when it is used to describe skin color, emerges in the language from the Dark Ages and from a multiplicity of ethnicities. A “white race” emerges into a proto- enlightenment and a proto-capitalism and into the uses of pigment. One way to deconstruct the notion of white supremacy is to parse the signification of the word “white.” In order to interrogate the politics of melanin we must confront what James Baldwin called “the lie that is whiteness.” We need to situate this signifier, this whiteness, in myth, ontology, aesthetics, metaphor, and ideology. In a more mundane physical description, white enters the world as light which is parsed by a prism that fractures white light into a spectrum – the colors of the rainbow. Each color of the spectrum vibrates on a different wavelength from infrared to ultraviolet. White and black have no wavelength. White contains and reflects all the colors; black absorbs all light and color. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Friday, June 8, 1973 the House Met at 12 O'clock Noon

r18730 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE JJJ-ne 8, 1973 tion that an employee is going to work for from the pension fund after his 8th year, five, or more jobs during his lifetime one company all or most of his career, and would have 100-percent vestment due to the mobility of this country's job and second, that a company will stay in after 15 years of service. market. Often a person will join a pen business forever in the same or expanded Many private pension plans lack ade sion plan each time he is employed and condition as it was when it installed its quate funding. Some companies put less then forfeits that money when he moves pension plan. money in the fund than they are re to a new place of employment. Conse We must realize, as the American quired to do by the pension agreement. quently, when he retires, all that money worker has realized, that we are in a mo Others switch the money to different ac is lost. This is obviously unfair. Thus, bile job market economy, where men and counts for their own purposes. Conse this bill creates a fund where deposits women frequently change their jobs. We quently, at times of financial crisis, a will be made by a member plan upon must realize too that our economy is go company may not be able to meet its ob request of the participant, equal to the ing through constant overhauling, which ligation to pay the participant the money current discounted value of the partici affects the security and stability of the he is owed. -

Thesis Understandingfootball Hooliganism Amón Spaaij Understanding Football Hooliganism

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Understanding football hooliganism : a comparison of six Western European football clubs Spaaij, R.F.J. Publication date 2007 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Spaaij, R. F. J. (2007). Understanding football hooliganism : a comparison of six Western European football clubs. Vossiuspers. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056294458-understanding- football-hooliganism.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 AUP/Spaaij 11-10-2006 12:54 Pagina 1 R UvA Thesis amón Spaaij Hooliganism Understanding Football Understanding Football Hooliganism Faculty of A Comparison of Social and Behavioural Sciences Six Western European Football Clubs Ramón Spaaij Ramón Spaaij is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and a Research Fellow at the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research. -

CT Ep 112 Transcription.Docx

Close Talking Episode #112 “October (2.)” by Louise Glück 10/23/20 https://soundcloud.com/close-talking/episode-112-october-louise-gluck Show Notes (Close Talking theme music) Connor 0:07 Hello and welcome to Close Talking the world's most popular poetry analysis podcasfrom Cardboardbox Productions Incorporated. I am co-host Connor McNamara Stratton, and with my good friend Jack Rossiter-Munley we read a poem, Jack 0:21 talk about the poem, Connor 0:23 and read the poem again. Jack 0:25 Before we get into today's selection, a quick note that if you like what we do here at Close Talking and you have a spare minute, it would mean the world to us if you would give the podcast a rating and review on Apple podcasts. Connor 0:36 Those ratings and reviews help boost us up the algorithm and find new listeners. And if you have suggestions for future episodes, or comments on this one, you can send us an email at [email protected]. You can also find us on social media; on Twitter the show is @closetalking. I'm @connormstratton and Jack is @jackrossitermun. Jack 1:00 On Instagram, the show is @closetalking and on Facebook it's facebook.com/closetalking. Connor 1:08 And our website where you can find all our past episodes is closetalking.com. And Cardboardbox Productions is going to have a newsletter. Stay tuned on social media for more information on how to subscribe. Jack 1:21 On with the show. Connor 1:31 Hello, and welcome to an all new episode of Close Talking.