CT Ep 112 Transcription.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

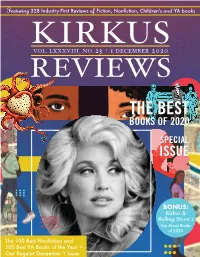

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

Culture Warlords, Such As It Is, Be Part Revenge, Part Explainer, and Partly the Story of What Hate Does to Those Who Observe It and Those Who Manufacture It

Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph Introduction Chapter 1: On Hating Chapter 2: The Jews Chapter 3: Boots on for the Boogaloo Chapter 4: Operation Ashlynn Chapter 5: Adventures with Incels Chapter 6: That Good Old-Time Religion Chapter 7: Tween Racists, Bad Beanies, and the Great Casino Chase Chapter 8: Getting to the Boom: On Accelerationism and Violence Chapter 9: Antifa Civil War Chapter 10: We Keep Us Safe Afterword Discover More Acknowledgments Endnotes Copyright © 2020 by Talia Lavin Cover design by Keith Hayes Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Hachette Books Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10104 HachetteBooks.com Twitter.com/HachetteBooks Instagram.com/HachetteBooks First Edition: October 2020 Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. -

Culture Warlords: My Journey Into the Dark Web of White Supremacy

Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 5(1), 15 ISSN: 2468-4414 Book Review Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacy Hope Kitts 1* Published: March 5, 2021 Book’s Author: Talia Lavin Publication Date: October 2020 Publisher: Hachette Books Price (Hardcover): $27/$34 (CAD) Number of Pages: 288 pp. ISBN-13: 9780306846434 With Culture Warlords (2020), Lavin ventures down the rabbit hole of hatred, misogyny and bigotry to re-emerge with knowledge you never knew you did not want to know. Lavin, a prolific freelance writer based in New York, begins with what seems to be individual antifascist sabotage of right-wing online communities, and proceeds to encompass a collective and common project. Her work builds to reveal law enforcement’s complicity with fascist organising and condemns major technology companies such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Telegram, and YouTube, which profit from underground international domestic terrorist networking. She clarifies the loose movement, known as Antifa, and aims to mobilise others to subvert fascist organising. She speaks to radicals, liberals and moderates alike – anyone who might defend hate speech on the basis of free speech, thus becoming complicit in the legacy of violence enacted in the name of the so-called pure, white race. Although focusing on white supremacy, she shows how misogyny intimately connects with ideologies promoting white supremacist violence. Lavin works in the company of her feminist predecessors, radical activist scholars who articulated the intertwined relationship between racism and misogyny (Combahee River Collective, 1979; Crenshaw, 1991; Davis, 1983; Lorde, 1984). -

HBG USA Fall 2021 - Page 1

GRAND CENTRAL PUBLISHING The Antisocial Network The GameStop Short Squeeze and the Ragtag Group of Amateur Traders That Brought Wall Street to Its Knees Ben Mezrich Summary The definitive account of the story of the year, the can’t-make-this-up Gamestop short squeeze—a David vs. Goliath tale of fortunes won and lost overnight that changed Wall Street forever. In The Antisocial Network, bestselling author Ben Mezrich tells the true story of the subreddit WallStreetBets, a loosely affiliated group of private investors and internet trolls who took down one of the biggest hedge funds on Wall Street, and in so doing, fired the first shot in a revolution that threatens to upend the financial establishment. Told with deep access, from multiple angles, it examines the culmination of a populist movement that began with the intersection of social media and the growth of simplified, democratizing financial Grand Central Publishing portals—represented by the biggest upstart in the business, RobinHood, and its millions of mostly millennial 9781538707555 Pub Date: 9/7/21 devotees. $28.00 USD/$35.00 CAD Hardcover The unlikely focus of the battle: GameStop, a flailing brick and mortar dinosaur catering to teenagers and 288 Pages outsiders, that had somehow outlived forbearers like Blockbuster Video and Petsmart as the world rapidly Carton Qty: 20 moved online. The story comes to a ... Print Run: 75K Business & Economics / Consumer Behavior Contributor Bio BUS016000 Ben Mezrich is the New York Times bestselling author of The Accidental Billionaires (adapted by Aaron Sorkin 9 in H | 6 in W into the David Fincher film The Social Network) and Bringing Down the House (adapted into the #1 box office hit film 21), as well as many other bestselling books. -

MZ 1/2016 Kern V11.Indd

ISSN 0259-7446 EUR 6,50 medienmedien Kommunikation in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart && zeitzeit Topic: The Balkans as the European Inner Otherness Being-with(out) Balkan Between Ethnic and Civic Nationalism Serbia‘s In-Betweenness Europe through the Gaze of the “Illustrirte Zeitung” Anno 1858 New Crisis, Old Perception? Research Corner: The Political Element in Serbian Public Discourse 11/2016/2016 Jahrgang 31 m&z 1/2016 medien & zeit Impressum MEDIENINHABER, HERAUSGEBER UND VERLEGER Verein „Arbeitskreis für historische Kommunikationsforschung Inhalt (AHK)“, Währinger Straße 29, 1090 Wien, ZVR-Zahl 963010743 http://www.medienundzeit.at © Die Rechte für die Beiträge in diesem Heft liegen beim „Arbeitskreis für historische Kommunikationsforschung (AHK)“ Being-with(out) Balkan HERAUSGEBERINNEN Rainer Gries, Christina Krakovsky, Eva Tamara Asboth; Eulogy for the Excess REDAKTION BUCHBESPRECHUNGEN Gaby Falböck, Roland Steiner, Thomas Ballhausen Mirjana Stošić 5 REDAKTION RESEARCH CORNER Rainer Gries LEKTORAT & LAYOUT Between Ethnic and Civic Nationalism Diotima Bertel, Barbara Metzler, Judith Rosenkranz, Catherine Sark; Census and Nation Building in Diotima Bertel, Catherine Sark Bosnia and Herzegovina PROOF READING Charlotte Eckler Anida Sokol 12 PREPRESS Grafikbüro Ebner, Wiengasse 6, 1140 Wien, VERSAND Serbia’s In-Betweenness ÖHTB – Österreichisches Hilfswerk für Taubblinde und hochgradig Hör- und Sehbehinderte The Interplay of Balkanism, Europeanness Werkstätte Humboldtplatz 7, 1100 Wien, ERSCHEINUNGSWEISE & BEZUGSBEDINGUNGEN and Disappointed Expectations in Serbia’s medien & zeit erscheint vierteljährlich gedruckt und digital. EU Integration Process Heftbestellungen: Einzelheft (exkl. Versand): 6,50 Euro Silvia Nadjivan 23 Jahresabonnement: Österreich (inkl. Versand): 22,00 Euro Ausland (inkl. Versand auf dem Landweg): 30,00 Euro Jahresabonnement für StudentInnen: Europe through the Gaze of the Österreich (inkl. -

Ponderthescriptures.Com Just Reporting American Democracy and Culture (Legislation, Budget Priorities, Voting Laws & Suppression, Corruption) R

ponderthescriptures.com just reporting american democracy and culture (legislation, budget priorities, voting laws & Suppression, corruption) r. scott burton “This is the Republicans’ back-up plan in case they can’t suppress enough votes,” Fred Hiatt, washingtonpost “‘The commitment of many state legislatures to attacking the foundations of our democracy appears to have deepened,’ says the report from Protect Democracy, States United Democracy Center and Law Forward. ‘The trend toward threatening election administrators with criminal penalties is more pronounced and aggressive, and attempts by legislatures to perform core elections functions has grown more brazen’... “Potentially most dangerous, legislatures are giving themselves the right to interfere in vote-counting and election disputes while tying the hands of secretaries of state to rule impartially or even in some cases to seek legal advice... “But bills giving legislators more oversight of elections, allowing them to interfere in the running of elections and otherwise injecting partisanship into the process, already have passed in Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas, according to the report. These could dramatically alter the outcome when a fraudster such as Trump comes calling... “It’s bad enough that most Republicans continue to defend Trump’s slander on American democracy and use it as a pretext to suppress the vote, instead of looking for ways to appeal to more voters. “It’s even scarier that they are trying to write themselves an insurance policy so that, if their vote suppression strategy fails in 2024, they can nonetheless reclaim power. “That should be unacceptable to every patriotic American.” “I Can’t Just Forgive Trump Supporters,” Jonathan Rigsby, medium “Every time I stop in traffic and see a Trump sticker on the car in front of me, I’m not struck by a sense that we have a disagreement over the details of policies. -

Tana French the Bestselling Crime Writer Had an Unexpected Inspiration for Her New Stand-Alone Novel P

Featuring 244 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 20 | 15 OCTOBER 2020 REVIEWS Tana French The bestselling crime writer had an unexpected inspiration for her new stand-alone novel p. 14 Also in the issue: Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Kwame Mbalia, and Tamara Payne from the editor’s desk: Don’t Know Much About History Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Last month, at a White House history conference, President Donald Trump Chief Executive Officer attacked the 1619 Project, a series of essays published in the New York Times MEG LABORDE KUEHN Magazine. The project—conceived by staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, with [email protected] Editor-in-Chief contributions by Matthew Desmond, Wesley Morris, and others—explores TOM BEER the centrality of slavery to the story of America. Trump claimed that the 1619 [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Project has been “discredited”—in fact, Hannah-Jones’ own essay won a Pulitzer SARAH KALINA Prize for Commentary—and groused that the “left has warped, distorted, and [email protected] defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies.” He called for Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU the establishment of a “1776 commission” to promote “patriotic education.” [email protected] Leaving aside the matter of nationally mandated “patriotic education”— Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK which sounds like something out of Stalin’s Soviet Union—the president clearly [email protected] Tom Beer misunderstands the nature of historiography, which involves not simply a fixed Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH set of facts, but an ongoing dialogue with historians past and present. -

Sea Change Talking Turkey

1 TALKING SEA CHANGE TURKEY Downsized Thanksgiving meals offer the opportunity for experimentation. NOVEMBER 12, 2020 / 25 CHESHVAN 5781 PAGE 19 JEWISHEXPONENT.COM WHAT IT MEANS TO BE JEWISH IN PHILADELPHIA $1.00 OF NOTE Palliative LOCAL Care Takes Havurah Marks 50th Anniversary on Added Strong friendships formed over the decades. Importance Page 4 During OBITUARY Len Barry Pandemic Dies at 78 The Dovells singer JESSE BERNSTEIN | JE STAFF had solo hits, too. DR. MARI SIEGEL FEELS fortunate to Page 6 be in palliative care, the eld of medicine BOOKS and health care dedicated to the mitiga- Joe Biden supporters celebrate outside of City Hall on Nov. 7. Photo by Gordon Cohen tion of su ering for patients with serious Complicated Life illnesses. It makes her feel like she’s invited of Max Jacob into a holy space — a space that’s usually Explored only shared with a rabbi. Biden Supporters Detail Also reviewed: “People trust me with their secrets, with world of white their feelings, with their loved one’s care,” Roles in Election Triumph supremacists. said Siegel, a palliative care physician at Temple University Hospital, and a member Page 21 of Adath Israel of the Main Line. “It really JESSE BERNSTEIN | JE STAFF president-elect and gave a victory speech does give me balance and ll my soul.” that night in Wilmington, Delaware. In the last few months, Siegel’s work AFTER ELECTION DAY, Jewish Pennsylvania has more than 430,000 Volume 133 has taken on a new element. Because the Philadelphians who worked on behalf of Joe Jewish residents, and many people played a Number 31 COVID-19 pandemic has put dangerously Biden’s campaign marched and danced, but role in getting that vote out. -

Full Text (Pdf)

FEMINIST ENCOUNTERS A JOURNAL OF CRITICAL STUDIES IN CULTURE AND POLITICS e-ISSN: 2542-4920 Volume 5, Issue 1 Spring 2021 Editor-in-Chief Sally R. Munt Sussex Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Sussex (UK) Guest Editors Amanda Gouws SARChI: Gender Politics, Stellenbosch University (SOUTH AFRICA) Deirdre Byrne University of South Africa (SOUTH AFRICA) Azille Coetzee Centre for Historical Trauma and Transformation, Stellenbosch University (SOUTH AFRICA) This page intentionally left blank. Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 1(1) ISSN: 2542-4920 CHIEF EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION FEMINIST ENCOUNTERS: A JOURNAL OF CRITICAL STUDIES IN CULTURE AND POLITICS Founded in 2017, Feminist Encounters is a journal committed to argument and debate, in the tradition of historical feminist movements. In the wake of the growing rise of the Right across the world, openly neo-fascist national sentiments, and rising conservative populism, we feminists all over the world are needing to remobilise our energies to protect and advance gender rights. Feminist Encounters provides a forum for feminist theorists, scholars, and activists to communicate with each other, to better educate ourselves on international issues and thus promote more global understanding, and to enhance our critical tools for fighting for human rights. Feminism is an intellectual apparatus, a political agenda, and a programme for social change. Critical analysis of how gender discourses produce cultural identities and social practices within diverse lived realities is key to this change. We need to think more sharply in order to strategise well: as the discourses of conservatism renew and invigorate themselves, so we as feminist scholars need to be refining our amazonic swords in order not just to respond effectively but also to innovate our own ideas for equality and social justice. -

RACE, GENDER and VIOLENCE on the TRANSATLANTIC EXTREME-RIGHT, 1969-2009 a Dissertation Presented by Simon

INTERSECTIONAL HATE: RACE, GENDER AND VIOLENCE ON THE TRANSATLANTIC EXTREME-RIGHT, 1969-2009 A dissertation presented By Simon A. Purdue To The Department of History In partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy In the fieLd of World History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts ApriL 2021 1 INTERSECTIONAL HATE: RACE, GENDER AND VIOLENCE ON THE TRANSATLANTIC EXTREME-RIGHT, 1969-2009 A dissertation presented By Simon A. Purdue ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION To The Department of History Submitted in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy in World History in the ColLege of SociaL Science and the Humanities of Northeastern University ApriL 2021 2 Abstract This dissertation seeks to get to the core of the racist extremist sociaL structure, focusing on the intimate and personaL politics of the movement and shifting our understanding of the neo-fascist weltanschauung on a globaL leveL. I explore the sociaL, politicaL and ideologicaL motivators that drive people towards the extreme-right and ultimateLy dictate their actions and beLiefs once they are firmLy within the movement, and my research highlights important trends and patterns that can have reaL-World impacts. For example, by exploring the intricacies of far-right masculinities in historicaL context we can determine key factors contributing to radicaLization towards violence, and can isolate particular warning signs that may be of great use to the professionaL Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) community. This dissertation is highly interdisciplinary and bridges the gap betWeen academia and an important nexus of policy, violence prevention, and security. My dissertation research has explored the intersection betWeen race and gender on the globaL extreme-right betWeen 1969 and 2009. -

978-1-59148-141-6-Telltruthshamedevil-2Nd-Lowres.Pdf

T ELL THE T RUTH AND S HAME THE D EVIL DEDICATION: For Germany. For Germans who still want to be German. For Humanity. Tell the Truth and Shame the Devil Recognize the True Enemy and Join to Fight Him !"# $ %&'( Gerard Menuhin: Tell the Tuth and Shame the Devil: Recognize the True Enemy and Join to Fight Him 2nd, expanded and corrected edition Uckfield, East Sussex: CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS PO Box 243, Uckfield, TN22 9AW, UK July 2016 ISBN10: 1-59148-141-4 ISBN13: 978-1-59148-141-6 Published by CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS Manufactured in the United States of America and in the UK © by Gerard Menuhin Distribution: Castle Hill Publishers, PO Box 243 Uckfield, TN22 9AW, UK shop.codoh.com Set in Garamond Cover Illustration: Man ripping off ivy from an oak tree; see pages 11 and 378f. of the present book. GERARD MENUHIN · TELL THE TRUTH & SHAME THE DEVIL 5 Table of Contents PREFACE 9 I THWARTED: HUMANITY’S LAST GRASP FOR FREEDOM 11 II IDENTIFIED: ILLUMINATION OR THE DIAGNOSTIC OF DARKNESS 155 III EXTINGUISHED: CIVILIZATION 265 IV FINAL STAGE: COMMUNIST VASSALAGE 325 Bibliography 401 Index of Names 415 GERARD MENUHIN · TELL THE TRUTH & SHAME THE DEVIL 7 “Sorrow is knowledge; they who know the most, must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth, the Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life.” —Manfred BYRON “Books are not memorials of the past, but weapons of the present age.” —Heinrich LAUBE GERARD MENUHIN · TELL THE TRUTH & SHAME THE DEVIL 9 Preface (Inspired by the description of the condemnation of Louis XVI) This book spans the time between 600 BC and the present day, and yet is also a personal journey. -

Christian Identity: an American Heresy

Christian Identity: An American Heresy Rev. David Ostendorf* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................ 24 II. BRITISH ISRAELISM AND THE ROOTS OF WHITE SUPREMACIST THEOLOGY IN AMERICA ................................ 26 A. An Ideology for Empire: British Israelism in the Nineteenth Century .......................................................... 27 B. The Leap of the Atlantic: Henry Ford and the Cauldrons of Anti-Semitism........................................................ 28 C. The Church of Jesus Christ Christian: Wesley Swift and American Identity ........................................... 29 III. “CHRISTIAN ISRAEL:” THE IDENTITY NOTION OF THE BIBLICAL TRIBES OF ISRAEL............................................................. 30 A. Name Games: The Re-Formation of Israel in the West ........................................................................ 31 B. The Tribes of Israel: The Heart of Identity’s Identity ........................................................................ 32 IV. OF JEWS AND (WHITE) CHRISTIANS: SEEDS OF SUPERIORITY .................................................................... 33 A. Adam: God’s White Man.......................................................... 34 B. Racial Purity: Fixed on Exclusion........................................... 35 C. Jews: The “Seed of Satan”...................................................... 36 V. J ESUS WAS AN ISRAELITE: IDENTITY CHRISTOLOGY .................... 37 A. Jesus: An Aryan Israelite,