Critiques of Cultural Decadence and Decline in British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Date 27/09/2021 00:07:53

The far right in the UK: The BNP in comparative perspective. Examining the development of the British Nation Party within the context of UK and continental far right politics Item Type Thesis Authors Anderson, Richard P. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 27/09/2021 00:07:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/5449 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BRITISH NATIONAL PARTY R.P.ANDERSON PhD UNIVERSITY OF BRADFORD 2011 THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BNP IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Examining the development of the British Nation Party within the context of UK and continental far right politics Richard Paul ANDERSON Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Development and Economic Studies University of Bradford 2011 2 Richard Paul ANDERSON THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BNP IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE British National Party, BNP, UK Politics, European politics, comparative politics, far right, racism, Griffin This thesis examines through the means of a comparative perspective, factors which have allowed the British National Party to enjoy recent electoral success at the local level under the leadership of party chairman Nick Griffin. -

The Local Impact of Falling Agricultural Prices and the Looming Prospect Of

CHAPTER SIX `BARLEY AND PEACE': THE BRITISH UNION OF FASCISTS IN NORFOLK, SUFFOLK AND ESSEX, 1938-1940 1. Introduction The local impact of falling agricultural prices and the looming prospectof war with Germany dominated Blackshirt political activity in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex from 1938. Growing resentment within the East Anglian farming community at diminishing returns for barley and the government's agricultural policy offered the B. U. F. its most promising opportunity to garner rural support in the eastern counties since the `tithe war' of 1933-1934. Furthermore, deteriorating Anglo-German relations induced the Blackshirt movement to embark on a high-profile `Peace Campaign', initially to avert war, and, then, after 3 September 1939, to negotiate a settlement to end hostilities. As part of the Blackshirts' national peace drive, B. U. F. Districts in the area pursued a range of propaganda activities, which were designed to mobilise local anti-war sentiment. Once again though, the conjunctural occurrence of a range of critical external and internal constraints thwarted B. U. F. efforts to open up political space in the region on a `barley and peace' platform. 2. The B. U. F., the `Barley Crisis' and the Farmers' March, 1938-1939 In the second half of 1938, falling agricultural prices provoked a fresh wave of rural agitation in the eastern counties. Although the Ministry of Agriculture's price index recorded a small overall reduction from 89.0 to 87.5 during 1937-1938, cereals due heavy from 1938 and farm crops were particularly affected to the yields the harvests. ' Compared with 1937 levels, wheat prices (excluding the subsidy) dropped by fourteen 2 Malting barley, by 35 per cent, barley by 23 per cent, and oats per cent. -

Propaganda Theatre : a Critical and Cultural Examination of the Work Of

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY PROPAGANDA THEATRE: A CRITICAL AND CULTURAL EXAMINATION OF THE WORK OF MORAL RE-ARMAMENT AT THE WESTMINSTER THEATRE, LONDON. PAMELA GEORGINA JENNER A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of PhD Submitted: June 2016 i Acknowledgements I am grateful to Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) for awarding me a three-year bursary in order to research this PhD. My thanks also go to my supervisory team: first supervisor Dr Susan Wilson, second supervisor Dr Nigel Ward, third supervisor Dr Jonathan Davis, fourth supervisor Dr Aldo Zammit-Baldo and also to IT advisor at ARU, Peter Carlton. I am indebted to Initiatives of Change for permission to access and publish material from its archives and in particular to contributions from IofC supporters including Hilary Belden, Dr Philip Boobbyer, Christine Channer, Fiona Daukes, Anne Evans, Chris Evans, David Hassell, Kay Hassell, Michael Henderson Stanley Kiaer, David Locke, Elizabeth Locke, John Locke; also to the late Louis Fleming and Hugh Steadman Williams. Without their enthusiasm and unfailing support this thesis could not have been written. I would also like to thank my family, Daniel, Moses and Richard Brett and Sanjukta Ghosh for their ongoing support. ii ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROPAGANDA THEATRE: A CRITICAL AND CULTURAL EXAMINATION OF THE WORK OF MORAL RE-ARMAMENT AT THE WESTMINSTER THEATRE, LONDON PAMELA GEORGINA JENNER JUNE 2016 This thesis investigates the rise and fall of the propagandist theatre of Moral Re-Armament (MRA), which owned the Westminster Theatre in London, from 1946 to 1997. -

Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship Between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 Alec J

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2017 Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 Alec J. Warren University of North Florida Suggested Citation Warren, Alec J., "Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951" (2017). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 755. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/755 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2017 All Rights Reserved BRITAIN’S GREEN FASCISTS: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 by Alec Jarrell Warren A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts in History UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES August, 2017 Unpublished work © Alec Jarrell Warren This Thesis of Alec Jarrell Warren is approved: Dr. Charles Closmann Dr. Chau Kelly Dr. Yanek Mieczkowski Accepted for the Department of History: Dr. Charles Closmann Chair Accepted for the College of Arts and Sciences: Dr. George Rainbolt Dean Accepted for the University: Dr. John Kantner Dean of the Graduate School ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family, who have always loved and supported me through all the highs and lows of my journey. Without them, this work would have been impossible. -

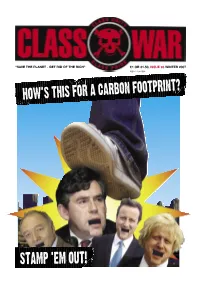

Stamp 'Em Out!

“SAVE THE PLANET - GET RID OF THE RICH” £1 OR €1.50, ISSUE 93 WINTER 2007 ISSN 1754-2804 How’s this for a carbon footprint? STAMp ‘em out! 2 CLASS WAR Winter 2007 being comforted in the arms of Jesse Jackson. Editorial: Now Class War is sure that Ken was genuinely moved to tears at the plight of the millions who were ripped from their homes to work themselves to death in order to enrich the City of London and that his actions HAD priced out NOTHING WHATSOEVER to do with his upcoming re- election campaign and his need to rebuild his support among black Londoners. Interestingly one of the key players at the start of of the market the British involvement in the slave trade was Queen Elizabeth I, as a shareholder and then, when she realised the money to be made, as ship owner. She lent her ship, the Jesus of Lubeck, to slave trader Sir The Bash the Rich demonstration on 3 November John Hawkins. He proudly flew the royal standard above his cargo of slaves. Does anyone think we will isn’t an end, but a beginning. It is the launch of see Queen Elizabeth II blubbing her way through an apology in this years Queens Speech? a new campaign about affordable housing for the working class, and against gentrification and the PC Plod Caught Porking On people who make gentrification possible. From The Job Limehouse to Leeds working class areas are “TAINTED LOVE” MASOOD KHAN, 41, a senior British Transport being invaded by yuppies, amenities sold off for Police inspector responsible for passenger safety across southeast England, has admitted meeting peanuts and communities ripped apart. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 Labour History Archive and Study Centre: Labour Party National Executive Committee Minutes, 1 March 1934. 2 See N. Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 2000), p. 76. 3 See J. Bean, Many Shades of Black: Inside Britain’s Far Right (London: New Millennium, 1999). 4 See Searchlight, no. 128, Feb. 1986, p. 15. 5 See for example, C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’, New Community, vol. 20, no. 4 (1994), pp. 563–79. 6 For discussion of legitimacy as a social-scientific concept, see D. Beetham, The Legitimation of Power (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1991). 7 For earlier work on the BNP by this author, see N. Copsey, ‘Fascism: The Ideology of the British National Party’, Politics, vol. 14, no. 3 (1994), pp. 101–8 and ‘Contemporary Fascism in the Local Arena: The British National Party and “Rights for Whites”’, in M. Cronin (ed.) The Failure of British Fascism: The Far Right and the Fight for Political Recognition (Basingstoke: Macmillan- Palgrave, 1996), pp. 118–40. For earlier work by others, see for example C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’; R. Eatwell, ‘Britain: The BNP and the Problem of Legitimacy’, in H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds), The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Estab- lished Democracies (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1998), pp. 143–55; and D. Renton, ‘Examining the Success of the British National Party, 1999–2003’, Race and Class, vol. -

Holocaust Revisionism

Holocaust Revisionism by Mark R. Elsis This article is dedicated to everyone before me who has been ostracized, vilified, reticulated, set up, threatened, lost their jobs, bankrupted, beaten up, fire bombed, imprisoned and killed for standing up and telling the truth on this historical subject. This is also dedicated to a true humanitarian for the people of Palestine who was savagely beaten and hung by the cowardly agents of the Mossad. Vittorio Arrigoni (February 4, 1975 - April 15, 2011) Holocaust Revisionism has two main parts. The first is an overview of information to help explain whom the Jews are and the death and carnage that they have inflicted on the Gentiles throughout history. The second part consists of 50 in-depth sections of evidence dealing with and repudiating every major facet of the Jewish "Holocaust " myth. History Of The Jews 50 Sections Of Evidence "You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, not holding to the truth, for there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies." Jesus Christ (assassinated after calling the Jews money changers) Speaking to the Jews in the Gospel of St. John, 8:44 I well know that this is the third rail of all third rail topics to discuss or write about, so before anyone takes this piece the wrong way, please fully hear me out. Thank you very much for reading this article and for keeping an open mind on this most taboo issue. -

Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation

STATE OF HATE 2021 BACKLASH, CONSPIRACIES & CONFRONTATION HOPE ACTION FUND We take on and defeat nazis. Will you step up with a donation to ensure we can keep fighting the far right? Setting up a Direct Debit to support our work is a quick, easy, and secure pro- cess – and it will mean you’re directly impacting our success. You just need your bank account number and sort code to get started. donate.hopenothate.org.uk/hope-action-fund STATE OF HATE 2021 Editor: Nick Lowles Deputy Editor: Nick Ryan Contributors: Rosie Carter Afrida Chowdhury Matthew Collins Gregory Davis Patrik Hermansson Roxana Khan-Williams David Lawrence Jemma Levene Nick Lowles Matthew McGregor Joe Mulhall Nick Ryan Liron Velleman HOPE not hate Ltd PO Box 61382 London N19 9EQ Registered office: Suite 1, 3rd Floor, 11-12 St. James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LB United Kingdom Tel.: +44 (207) 9521181 www.hopenothate.org.uk @hope.n.hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate | 3 STATE OF HATE 2021 CONTENTS SECTION 1 – OVERVIEW P6 SECTION 3 – COVID AND CONSPIRACIES P36 38 COVID-19, Conspiracy Theories And The Far Right 44 Conspiracy Theory Scene 48 Life After Q? 6 Editorial 52 UNMASKED: The QAnon ‘Messiah’ 7 Executive Summary 54 The Qanon Scene 8 Overview: Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation 56 From Climate Denial To Blood and Soil SECTION 2 – RACISM P14 16 Hate Crimes Summary: 2020 20 The Hostile Environment That Never Went Away 22 How BLM Changed The Conversation On Race 28 Whitelash: Reaction To BLM And Statue Protests 31 Livestream Against The Mainstream -

The Radical Right in Britain

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Right in Britain Matthew Feldman Director, Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical right has been small, fractious yet British Union of Fascists, including Neil Francis persistent in nearly a century of activism at the furthest Hawkins, E.G. Mandeville Roe, H.J. Donavan, and reaches of the right-wing spectrum. As this collection William Joyce.iv In 1937, the latter would form one of of primary source documents makes plain, moreover, many small fascist parties in interwar Britain, and there are also a number of surprising elements in perhaps the most extreme: the National Socialist British fascism that were not observed elsewhere. League – in the roiling years to come, Joyce took up the While there had long been exclusionary, racist, and mantle of ‘Lord Haw Haw’ for the Nazi airwaves, for anti-democratic groups in Britain, as on the continent, which he would be one of two people hanged for it was the carnage and dislocation of the Great War treason in 1946 (the other was John Amery, who tried (1914-18) that gave fascism its proper push over the to recruit British prisoners of war to fight on behalf of top. Some five years after the 11 November 1918 the Third Reich). Other tiny and, more often than not, armistice – a much longer gestation period than on the aristocratic fascist movements in interwar Britain continent – ‘the first explicitly fascist movement in included The Link, The Right Club, the Anglo-German Britain’ was the British Fascisti (BF).i Highly unusual Fellowship, The Nordic League, and English Mistery for a fascist movement at the time, or since, it was led (and its offshoot movement, English Array).v by a woman, Rotha Linton-Orman. -

British Fascism from a Transnational Perspective, 1923 to 1939

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive Breaking Boundaries: British Fascism from a Transnational Perspective, 1923 to 1939 MAY, Rob Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26108/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version MAY, Rob (2019). Breaking Boundaries: British Fascism from a Transnational Perspective, 1923 to 1939. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Breaking Boundaries: British Fascism from a Transnational Perspective, 1923 to 1939 Robert May A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 I hereby declare that: 1. I have been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. I was an enrolled student for the following award: Postgraduate Certificate in Arts and Humanities Research University of Hull 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Original Flyer for the Last Resort CHAPTER ONE 1977–1979

58 THE WHITE NATIONALIST SKINHEAD MOVEMENT Original flyer for the Last Resort CHAPTER ONE 1977–1979 National Front By the mid-1970s Britain was polarised like never before. The reason for this was the emergence of the National Front. Founded in 1967, the National Front [NF], a right-wing political party, campaigned for an end to ‘coloured’ immigration, the humane repatria- tion of immigrants living in Britain, withdrawal from the European community, and the reintroduction of capital punishment. Even though the NF regarded ‘International Communism as the number one ene- my of civilization’ and ‘International Monopoly Capitalism’ as dangerous an enemy as communism, only one issue was ever likely to arouse the feelings of the masses and that was race. And racial tension was running high because of the large influx of immi- grants from the Commonwealth, which the NF exploited to the full. Indeed, the expul- sion of all Asians with British passports from Uganda by General Idi Amin and their arrival in Britain had ignited widespread popular protests. If ever the political climate was favourable for the growth of an openly racist right-wing party the time was now. The 1973 West Bromwich by-election shocked many when the NF candidate, Martin Webster, managed to poll 16.2 percent of the votes, coming in third and saving his deposit for the first time in the NF’s history. This was a danger sign to the major parties that NF support was on the increase in certain areas, particularly those badly hit by the recession with considerable social problems. -

U.S. Senators: Vote YES on the Disability Treaty! © Nicolas Früh/Handicap International November 2013 Dear Senator

U.S. Senators: Vote YES on the Disability Treaty! © Nicolas Früh/Handicap International November 2013 Dear Senator, The United States of America has always been a leader of the rights of people with disabilities. Our country created the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), ensuring the rights of 57.8 million Americans with disabilities, including 5.5 million veterans. The ADA inspired the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) treaty. The CRPD ensures that the basic rights we enjoy, such as the right to work and be healthy, are extended to all people with disabilities. Last December, America’s leadership diminished when the Senate failed to ratify the CRPD by 5 votes. In the pages that follow, you will find the names of 67,050 Americans who want you to vote Yes on the CRPD. Their support is matched by more than 800 U.S. organizations, including disability, civil rights, veterans’ and faith-based organizations. These Americans know the truth: • Ratification furthers U.S. leadership in upholding, championing and protecting the rights of children and adults with disabilities • Ratification benefits all citizens working, studying, or traveling overseas • Ratification creates the opportunity for American businesses and innovations to reach international markets • Ratification does not require changes to any U.S. laws • Ratification does not jeopardize U.S. sovereignty The Senate has an opportunity that doesn’t come along often in Washington—a second chance to do the right thing and to ratify the CRPD. We urge you and your fellow Senators to support the disability treaty with a Yes vote when it comes to the floor.We must show the world that U.S.