Download Date 27/09/2021 00:07:53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal Brakes the British Extreme Right (Pdf

FEBRUARY 2019 The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation The British extreme right in the 1990s ANNEX B Joel Busher, Coventry University Donald Holbrook, University College London Graham Macklin, Oslo University This report is the second empirical case study, produced out of The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation: A Descriptive Typology programme, funded by CREST. You can read the other two case studies; The Trans-national and British Islamist Extremist Groups and The Animal Liberation Movement, plus the full report at: https://crestresearch.ac.uk/news/internal- brakes-violent-escalation-a-descriptive-typology/ To find out more information about this programme, and to see other outputs from the team, visit the CREST website at: www.crestresearch.ac.uk/projects/internal-brakes-violent-escalation/ About CREST The Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) is a national hub for understanding, countering and mitigating security threats. It is an independent centre, commissioned by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and funded in part by the UK security and intelligence agencies (ESRC Award: ES/N009614/1). www.crestresearch.ac.uk ©2019 CREST Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC-SA licence. www.crestresearch.ac.uk/copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................5 2. INTERNAL BRAKES ON VIOLENCE WITHIN THE BRITISH EXTREME RIGHT .................10 2.1 BRAKE 1: STRATEGIC LOGIC .......................................................................................................................................10 -

The European Election Results 2009

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION FOR THE EASTERN REGION 4TH JUNE 2009 STATEMENT UNDER RULE 56(1)(b) OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS RULES 2004 I, David Monks, hereby give notice that at the European Parliamentary Election in the Eastern Region held on 4th June 2009 — 1. The number of votes cast for each Party and individual Candidate was — Party or Individual Candidate No. of Votes 1. Animals Count 13,201 2. British National Party – National Party – Protecting British Jobs 97,013 3. Christian Party ―Proclaiming Christ’s Lordship‖ The Christian Party – CPA 24,646 4. Conservative Party 500,331 5. English Democrats Party – English Democrats – ―Putting England First!‖ 32,211 6. Jury Team 6,354 7. Liberal Democrats 221,235 8. NO2EU:Yes to Democracy 13,939 9 Pro Democracy: Libertas.EU 9,940 10. Social Labour Party (Leader Arthur Scargill) 13,599 11. The Green Party 141,016 12. The Labour Party 167,833 13. United Kingdom First 38,185 14. United Kingdom Independence Party – UKIP 313,921 15. Independent (Peter E Rigby) 9,916 2. The number of votes rejected was: 13,164 3. The number of votes which each Party or Candidate had after the application of subsections (4) to (9) of Section 2 of the European Parliamentary Elections Act 2002, was — Stage Party or Individual Candidate Votes Allocation 1. Conservative 500331 First Seat 2. UKIP 313921 Second Seat 3. Conservative 250165 Third Seat 4. Liberal Democrat 221235 Fourth Seat 5. Labour Party 167833 Fifth Seat 6. Conservative 166777 Sixth Seat 7. UKIP 156960 Seventh Seat 4. The seven Candidates elected for the Eastern Region are — Name Address Party 1. -

British National Party: the Roots of Its Appeal Contents Contents About the Authors 4 TABLES and FIGURES

The BNP: the roots of its appeal Peter John, Helen Margetts, David Rowland and Stuart Weir Democratic Audit, Human Rights Centre, University of Essex Published by Democratic Audit, Human Rights Centre, University of Essex, Colchester, Essex CO4 3SQ, and based on research carried out at the School of Public Policy, University College London, The Rubin Building, 29-30 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9QU.The research was sponsored by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, The Garden House, Water End, York YO30 6WQ. Copies of the report may be obtained for £10 from the Trust office. Democratic Audit is a research organisation attached to the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex. The Audit specialises in auditing democracy and human rights in the UK and abroad and has developed a robust and flexible framework for democracy assessment in cooperation with the inter-governmental International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), Stockholm. The Audit carries out periodic research projects as part of its longitudinal studies of British democracy. The latest audit of the UK, Democracy under Blair, is published by Politico’s. University College London’s Department of Political Science and School of Public Policy is focused on graduate teaching and research, and offers an environment for the study of all fields of politics, including international relations, political theory and public policy- making and administration 2 The British National Party: the roots of its appeal Contents Contents About the Authors 4 TABLES AND FIGURES -

Direct Download

The Journal of Public Space 2018 | Vol. 3 n. 1 https://www.journalpublicspace.org EDITORIAL TEAM Editor in Chief Luisa Bravo, City Space Architecture, Italy Scientific Board Davisi Boontharm, Meiji University, Japan Simone Brott, Queensland University of Technology, Australia SPACE Julie-Anne Carroll, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Margaret Crawford, University of California Berkeley, United States of America Philip Crowther, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Simone Garagnani, University of Bologna, Italy PUBLIC Pietro Garau, University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Italy Carl Grodach, Monash University, Australia OF Chye Kiang Heng, National University of Singapore, Singapore Miquel Marti, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Spain Maggie McCormick, RMIT University, Australia Darko Radovic, Keio University, Japan Estanislau Roca, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Spain JOURNAL Joaquin Sabate, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Spain Robert Saliba, American University of Beirut, Lebanon Claudio Sgarbi, Carleton University, Canada THE Hendrik Tieben, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Strategic Advisory Board Cecilia Andersson, UN-Habitat Global Public Space Programme, Kenya Tigran Haas, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden Michael Mehaffy, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden Laura Petrella, UN-Habitat Global Public Space Programme, Kenya Advisory Board for Research into Action Ethan Kent, Project for Public Spaces, United States of America Gregor Mews, Urban Synergies Group, Australia Luis -

Critiques of Cultural Decadence and Decline in British

Purifying the Nation: British Neo-Fascist Ideas on Representations of Culture Steven Woodbridge, Kingston University Paper for the ‘Dangerous Representations’ multi-disciplinary Conference, Sussex University, June, 2001 Introduction Although fascism and neo-fascism have emphasised ‘action’ in politics, we should not underestimate the extent to which far right ideologues have sought to engage in the intellectual and cultural arena. This paper investigates the ideas, attitudes and discourse of the post-1945 British far right concerning representations of culture. I will argue that the ideological texts of the far right show a recurrent concern with the need for the so-called ‘purification’ of national culture. In essence, there is a belief expounded by the extreme right that ‘liberal’ cultural forms have resulted in national decadence, in turn showing the extent to which the nation itself is in serious decline. Consequently, there has been a consistent call in far right texts and statements for the ‘regeneration’ of the nation, together with the expression of a conviction that national culture requires ‘cleansing’ as part of this ambitious project. The far right’s key ideologues in Britain have regularly expressed views on what constitutes ‘true’, legitimate and authentically ‘British’ cultural representations, and they have often pointed to what is (in their estimation) ‘decadent’ versus ‘healthy’ cultural and national identities. It is intended in this paper to illustrate the far right’s prescription for political and cultural renewal through a brief exploration of the intellectual texts of three neo- fascist movements operating after 1945: the Union Movement (UM), formed in 1948, the National Front (NF), formed in 1967, and the British National Party (BNP), 1 formed in 1982. -

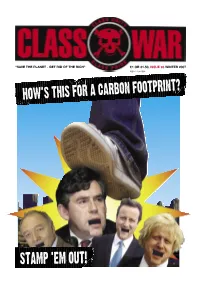

Stamp 'Em Out!

“SAVE THE PLANET - GET RID OF THE RICH” £1 OR €1.50, ISSUE 93 WINTER 2007 ISSN 1754-2804 How’s this for a carbon footprint? STAMp ‘em out! 2 CLASS WAR Winter 2007 being comforted in the arms of Jesse Jackson. Editorial: Now Class War is sure that Ken was genuinely moved to tears at the plight of the millions who were ripped from their homes to work themselves to death in order to enrich the City of London and that his actions HAD priced out NOTHING WHATSOEVER to do with his upcoming re- election campaign and his need to rebuild his support among black Londoners. Interestingly one of the key players at the start of of the market the British involvement in the slave trade was Queen Elizabeth I, as a shareholder and then, when she realised the money to be made, as ship owner. She lent her ship, the Jesus of Lubeck, to slave trader Sir The Bash the Rich demonstration on 3 November John Hawkins. He proudly flew the royal standard above his cargo of slaves. Does anyone think we will isn’t an end, but a beginning. It is the launch of see Queen Elizabeth II blubbing her way through an apology in this years Queens Speech? a new campaign about affordable housing for the working class, and against gentrification and the PC Plod Caught Porking On people who make gentrification possible. From The Job Limehouse to Leeds working class areas are “TAINTED LOVE” MASOOD KHAN, 41, a senior British Transport being invaded by yuppies, amenities sold off for Police inspector responsible for passenger safety across southeast England, has admitted meeting peanuts and communities ripped apart. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 Labour History Archive and Study Centre: Labour Party National Executive Committee Minutes, 1 March 1934. 2 See N. Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 2000), p. 76. 3 See J. Bean, Many Shades of Black: Inside Britain’s Far Right (London: New Millennium, 1999). 4 See Searchlight, no. 128, Feb. 1986, p. 15. 5 See for example, C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’, New Community, vol. 20, no. 4 (1994), pp. 563–79. 6 For discussion of legitimacy as a social-scientific concept, see D. Beetham, The Legitimation of Power (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1991). 7 For earlier work on the BNP by this author, see N. Copsey, ‘Fascism: The Ideology of the British National Party’, Politics, vol. 14, no. 3 (1994), pp. 101–8 and ‘Contemporary Fascism in the Local Arena: The British National Party and “Rights for Whites”’, in M. Cronin (ed.) The Failure of British Fascism: The Far Right and the Fight for Political Recognition (Basingstoke: Macmillan- Palgrave, 1996), pp. 118–40. For earlier work by others, see for example C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’; R. Eatwell, ‘Britain: The BNP and the Problem of Legitimacy’, in H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds), The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Estab- lished Democracies (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1998), pp. 143–55; and D. Renton, ‘Examining the Success of the British National Party, 1999–2003’, Race and Class, vol. -

Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation

STATE OF HATE 2021 BACKLASH, CONSPIRACIES & CONFRONTATION HOPE ACTION FUND We take on and defeat nazis. Will you step up with a donation to ensure we can keep fighting the far right? Setting up a Direct Debit to support our work is a quick, easy, and secure pro- cess – and it will mean you’re directly impacting our success. You just need your bank account number and sort code to get started. donate.hopenothate.org.uk/hope-action-fund STATE OF HATE 2021 Editor: Nick Lowles Deputy Editor: Nick Ryan Contributors: Rosie Carter Afrida Chowdhury Matthew Collins Gregory Davis Patrik Hermansson Roxana Khan-Williams David Lawrence Jemma Levene Nick Lowles Matthew McGregor Joe Mulhall Nick Ryan Liron Velleman HOPE not hate Ltd PO Box 61382 London N19 9EQ Registered office: Suite 1, 3rd Floor, 11-12 St. James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LB United Kingdom Tel.: +44 (207) 9521181 www.hopenothate.org.uk @hope.n.hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate @hopenothate HOPE not hate | 3 STATE OF HATE 2021 CONTENTS SECTION 1 – OVERVIEW P6 SECTION 3 – COVID AND CONSPIRACIES P36 38 COVID-19, Conspiracy Theories And The Far Right 44 Conspiracy Theory Scene 48 Life After Q? 6 Editorial 52 UNMASKED: The QAnon ‘Messiah’ 7 Executive Summary 54 The Qanon Scene 8 Overview: Backlash, Conspiracies & Confrontation 56 From Climate Denial To Blood and Soil SECTION 2 – RACISM P14 16 Hate Crimes Summary: 2020 20 The Hostile Environment That Never Went Away 22 How BLM Changed The Conversation On Race 28 Whitelash: Reaction To BLM And Statue Protests 31 Livestream Against The Mainstream -

The Radical Right in Britain

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Right in Britain Matthew Feldman Director, Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical right has been small, fractious yet British Union of Fascists, including Neil Francis persistent in nearly a century of activism at the furthest Hawkins, E.G. Mandeville Roe, H.J. Donavan, and reaches of the right-wing spectrum. As this collection William Joyce.iv In 1937, the latter would form one of of primary source documents makes plain, moreover, many small fascist parties in interwar Britain, and there are also a number of surprising elements in perhaps the most extreme: the National Socialist British fascism that were not observed elsewhere. League – in the roiling years to come, Joyce took up the While there had long been exclusionary, racist, and mantle of ‘Lord Haw Haw’ for the Nazi airwaves, for anti-democratic groups in Britain, as on the continent, which he would be one of two people hanged for it was the carnage and dislocation of the Great War treason in 1946 (the other was John Amery, who tried (1914-18) that gave fascism its proper push over the to recruit British prisoners of war to fight on behalf of top. Some five years after the 11 November 1918 the Third Reich). Other tiny and, more often than not, armistice – a much longer gestation period than on the aristocratic fascist movements in interwar Britain continent – ‘the first explicitly fascist movement in included The Link, The Right Club, the Anglo-German Britain’ was the British Fascisti (BF).i Highly unusual Fellowship, The Nordic League, and English Mistery for a fascist movement at the time, or since, it was led (and its offshoot movement, English Array).v by a woman, Rotha Linton-Orman. -

Local Election Results 2006

Local Election Results May 2006 Andrew Teale July 29, 2013 2 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2006 Typeset by LATEX Compilation and design © Andrew Teale, 2011. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. This file is available for download from http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/ The LATEX source code is available for download at http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/pdf/2006/2006-source.zip Please advise the author of any corrections which need to be made by email: [email protected] Change Log 29 July 2013: Corrected gain information for Derby. Chaddesden ward was a Labour hold; Chellaston ward was a Labour gain from Conservative. 23 June 2013: Corrected result for Plymouth, Southway. The result previously shown was for a June 2006 by-election. Contents I London Boroughs 11 1 North London 12 1.1 Barking and Dagenham....................... 12 1.2 Barnet.................................. 14 1.3 Brent.................................. 17 1.4 Camden................................ 20 1.5 Ealing.................................. 23 1.6 Enfield................................. 26 1.7 Hackney................................ 28 1.8 Hammersmith and Fulham...................... 31 1.9 Haringey................................ 33 1.10 Harrow................................. 36 1.11 Havering................................ 39 1.12 Hillingdon............................... 42 1.13 Hounslow............................... 45 1.14 Islington................................ 47 1.15 Kensington and Chelsea....................... 50 1.16 Newham................................ 52 1.17 Redbridge............................... 56 1.18 Tower Hamlets........................... -

Ratnoff Euroscepticism Thesis

The Long Brexit: Postwar British Euroscepticism By David Ratnoff Peter C. Caldwell, Ph.D. A thesis submitted to the Undergraduate Studies Committee of the Department of History of Rice University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History with Honors. Houston 2018 Table of Contents Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................ii Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Disunion on the Right: Britain’s Relationship with Europe in the Early Postwar Period ...... 9 2. Labour’s Euroscepticism and the Heightened Lure of 1960s Europe.................................. 25 3. Resurgent British Nationalism During European Integration, 1973-1992 ........................... 41 4. After Thatcher: From Europhilic Government to Eurosceptic Consensus........................... 66 5. From Bloomberg to Brexit ................................................................................................ 95 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 115 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

European Parliament Information Office in the Uk Media Guide 2011

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT INFORMATION OFFICE IN THE UK MEDIA GUIDE 2011 www.europarl.org.uk 2011 01 02 03 52 1 2 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 12 13 1 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 7 14 21 28 2 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 1 8 15 22 29 3 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 2 9 16 23 30 4 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 3 10 17 24 31 5 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 4 11 18 25 6 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 5 12 19 26 7 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 6 13 20 27 04 05 06 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 1 4 11 18 25 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 2 5 12 19 26 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 3 6 13 20 27 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 4 7 14 21 28 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 5 1 8 15 22 29 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 6 2 9 16 23 30 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 7 3 10 17 24 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 07 08 09 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 35 36 37 38 39 1 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 2 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 3 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 4 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 5 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 6 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 7 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 10 11 12 39 40 41 42 43 44 44 45 46 47 48 48 49 50 51 52 1 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 5 12 19 26 2 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 6 13 20 27 3 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 7 14 21 28 4 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 1 8 15 22 29 5 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 2 9 16 23 30 6 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 3 10 17 24 31 7 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 4 11 18 25 Неделя / Domingo / Nedĕle / Søndag / Sonntag / pühapäev / Κυριακή / Sunday / Dimanche / Domhnach / Domenica / svētdiena / sekmadienis / 7 Vasárnap / II-Ħadd / Zondag / Niedziela / Domingo / duminică / nedeľa / nedelja