The Rise and Fall of the British National Party, 2009-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandatory Data Retention by the Backdoor

statewatch monitoring the state and civil liberties in the UK and Europe vol 12 no 6 November-December 2002 Mandatory data retention by the backdoor EU: The majority of member states are adopting mandatory data retention and favour an EU-wide measure UK: Telecommunications surveillance has more than doubled under the Labour government A special analysis on the surveillance of telecommunications by states have, or are planning to, introduce mandatory data Statewatch shows that: i) the authorised surveillance in England, retention (only two member states appear to be resisting this Wales and Scotland has more than doubled since the Labour move). In due course it can be expected that a "harmonising" EU government came to power in 1997; ii) mandatory data retention measure will follow. is so far being introduced at national level in 9 out of 15 EU members states and 10 out of 15 favour a binding EU Framework Terrorism pretext for mandatory data retention Decision; iii) the introduction in the EU of the mandatory Mandatory data retention had been demanded by EU law retention of telecommunications data (ie: keeping details of all enforcement agencies and discussed in the EU working parties phone-calls, mobile phone calls and location, faxes, e-mails and and international fora for several years prior to 11 September internet usage of the whole population of Europe for at least 12 2000. On 20 September 2001 the EU Justice and Home Affairs months) is intended to combat crime in general. Council put it to the top of the agenda as one of the measures to combat terrorism. -

Far-Right Anthology

COUNTERINGDEFENDING EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDTHE THEFAR FUTURE RIGHT: OFAN EUROPEAN ANTHOLOGY GEOPOLITICSEDITED BY DR RAKIB EHSAN AND DR PAUL STOTT BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportApril No 2020. 2018/1 Published in 2020 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank London SW1P 4QP Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2020. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its Trustees. Title: “COUNTERING THE FAR RIGHT: AN ANTHOLOGY” Edited by Dr Rakib Ehsan and Dr Paul Stott Front Cover: Edinburgh, Scotland, 23rd March 2019. Demonstration by the Scottish Defence League (SDL), with supporters of National Front and white pride, and a counter demonstration by Unite Against Facism demonstrators, outside the Scottish Parliament, in Edinburgh. The Scottish Defence League claim their protest was against the sexual abuse of minors, but the opposition claim the rally masks the SDL’s racist beliefs. Credit: Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Alamy Live News. COUNTERINGDEFENDING EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDTHE THEFAR FUTURE RIGHT: OFAN EUROPEAN ANTHOLOGY GEOPOLITICSEDITED BY DR RAKIB EHSAN AND DR PAUL STOTT BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportApril No 2020. 2018/1 Countering the Far Right: An Anthology About the Editors Dr Paul Stott joined the Henry Jackson Society’s Centre on Radicalisation and Terrorism as a Research Fellow in January 2019. An experienced academic, he received an MSc in Terrorism Studies (Distinction) from the University of East London in 2007, and his PhD in 2015 from the University of East Anglia for the research “British Jihadism: The Detail and the Denial”. -

Internal Brakes the British Extreme Right (Pdf

FEBRUARY 2019 The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation The British extreme right in the 1990s ANNEX B Joel Busher, Coventry University Donald Holbrook, University College London Graham Macklin, Oslo University This report is the second empirical case study, produced out of The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation: A Descriptive Typology programme, funded by CREST. You can read the other two case studies; The Trans-national and British Islamist Extremist Groups and The Animal Liberation Movement, plus the full report at: https://crestresearch.ac.uk/news/internal- brakes-violent-escalation-a-descriptive-typology/ To find out more information about this programme, and to see other outputs from the team, visit the CREST website at: www.crestresearch.ac.uk/projects/internal-brakes-violent-escalation/ About CREST The Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) is a national hub for understanding, countering and mitigating security threats. It is an independent centre, commissioned by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and funded in part by the UK security and intelligence agencies (ESRC Award: ES/N009614/1). www.crestresearch.ac.uk ©2019 CREST Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC-SA licence. www.crestresearch.ac.uk/copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................5 2. INTERNAL BRAKES ON VIOLENCE WITHIN THE BRITISH EXTREME RIGHT .................10 2.1 BRAKE 1: STRATEGIC LOGIC .......................................................................................................................................10 -

British National Party: the Roots of Its Appeal Contents Contents About the Authors 4 TABLES and FIGURES

The BNP: the roots of its appeal Peter John, Helen Margetts, David Rowland and Stuart Weir Democratic Audit, Human Rights Centre, University of Essex Published by Democratic Audit, Human Rights Centre, University of Essex, Colchester, Essex CO4 3SQ, and based on research carried out at the School of Public Policy, University College London, The Rubin Building, 29-30 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9QU.The research was sponsored by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, The Garden House, Water End, York YO30 6WQ. Copies of the report may be obtained for £10 from the Trust office. Democratic Audit is a research organisation attached to the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex. The Audit specialises in auditing democracy and human rights in the UK and abroad and has developed a robust and flexible framework for democracy assessment in cooperation with the inter-governmental International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), Stockholm. The Audit carries out periodic research projects as part of its longitudinal studies of British democracy. The latest audit of the UK, Democracy under Blair, is published by Politico’s. University College London’s Department of Political Science and School of Public Policy is focused on graduate teaching and research, and offers an environment for the study of all fields of politics, including international relations, political theory and public policy- making and administration 2 The British National Party: the roots of its appeal Contents Contents About the Authors 4 TABLES AND FIGURES -

Download Date 27/09/2021 00:07:53

The far right in the UK: The BNP in comparative perspective. Examining the development of the British Nation Party within the context of UK and continental far right politics Item Type Thesis Authors Anderson, Richard P. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 27/09/2021 00:07:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/5449 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BRITISH NATIONAL PARTY R.P.ANDERSON PhD UNIVERSITY OF BRADFORD 2011 THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BNP IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Examining the development of the British Nation Party within the context of UK and continental far right politics Richard Paul ANDERSON Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Development and Economic Studies University of Bradford 2011 2 Richard Paul ANDERSON THE FAR RIGHT IN THE UK: THE BNP IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE British National Party, BNP, UK Politics, European politics, comparative politics, far right, racism, Griffin This thesis examines through the means of a comparative perspective, factors which have allowed the British National Party to enjoy recent electoral success at the local level under the leadership of party chairman Nick Griffin. -

BNP ––– the Ugly Truth

BNP ––– The ugly truth By Charles Walker MP A Cornerstone Paper Despite a disastrous performance in terms of new seats gained (early analysis of results suggests a net gain of one has already been cancelled out by a defection in Stoke) at the recent May 3 rd Poll in England and Wales, the BNP continues to retain a toehold in British politics. Of course, we should not over play the importance of a political movement that struggles to hold its deposit at general elections and still only has a handful of councillors. However, having polled over 300,000 votes in the English local elections and 42,000 votes in the Welsh Assembly poll, the night was not a total washout for Mr Griffin and his colleagues. Such is the creeping malevolence of the BNP, it would be grossly negligent of mainstream political parties if they did not take the threat it poses seriously. One only has to look across the Channel towards mainland Europe to realise that wishing fascists away does not work. The BNP had been emboldened by its November 2006 courtroom success that saw its Leader Nick Griffin cleared of preaching and promoting racial hatred. The prosecution of Griffin was wholly misconceived and looked likely to end in failure from the moment charges were laid. It can only be hoped that lessons have been learnt by the “establishment” and such cack-handedness will be avoided in the future. Despite the continued efforts of Griffin to reposition his party away from its thuggish past, the BNP remains a deeply flawed and racist organisation. -

'Nationalist' Economic Policy John E. Richardson

The National Front, and the search for a ‘nationalist’ economic policy John E. Richardson (forthcoming 2017) To be included in Copsey, N. & Worley, M. (eds) 'Tomorrow Belongs to Us': The British Far- Right Since 1967 Summarizing the economic policies of the National Front (NF) is a little problematic. Compared to their copious discussion of race and nation, of immigration, culture, history and even the environment, British fascists since WWII have had little to say, in detail, on their political-economic ideology. In one of the first content analytic studies of the NF’s mouthpiece Spearhead, for example, Harris (1973) identified five themes which dominated the magazine’s all pervasive conspiracy thinking: authoritarianism, ethnocentrism, racism, biological naturalism and anti-intellectualism. The economy was barely discussed, other than in the context of imagined generosity of the welfare state. The topic is so under-developed that even Rees’ (1979) encyclopaedic bibliography on British fascism, covering over 800 publications on and by fascists (between 1923-1977) doesn’t include a section on political economy. Frequently, the closest fascists get to outlining their political-economic ideology is to identify ‘the problem’: the forces of ‘cosmopolitan internationalism’ (that is: the Jews) importing migrants, whose cheap labour threatens white livelihoods, and whose physical presence threatens the racial purity of the nation. ‘The solution’, on the other hand, is far less frequently spelled out. In essence, fascist parties, like the NF, are comparatively clear about what political economies they oppose – international capitalism and international communism – but are far less clear or consistent about the political economy they support. -

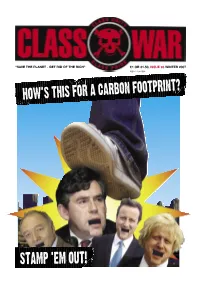

Stamp 'Em Out!

“SAVE THE PLANET - GET RID OF THE RICH” £1 OR €1.50, ISSUE 93 WINTER 2007 ISSN 1754-2804 How’s this for a carbon footprint? STAMp ‘em out! 2 CLASS WAR Winter 2007 being comforted in the arms of Jesse Jackson. Editorial: Now Class War is sure that Ken was genuinely moved to tears at the plight of the millions who were ripped from their homes to work themselves to death in order to enrich the City of London and that his actions HAD priced out NOTHING WHATSOEVER to do with his upcoming re- election campaign and his need to rebuild his support among black Londoners. Interestingly one of the key players at the start of of the market the British involvement in the slave trade was Queen Elizabeth I, as a shareholder and then, when she realised the money to be made, as ship owner. She lent her ship, the Jesus of Lubeck, to slave trader Sir The Bash the Rich demonstration on 3 November John Hawkins. He proudly flew the royal standard above his cargo of slaves. Does anyone think we will isn’t an end, but a beginning. It is the launch of see Queen Elizabeth II blubbing her way through an apology in this years Queens Speech? a new campaign about affordable housing for the working class, and against gentrification and the PC Plod Caught Porking On people who make gentrification possible. From The Job Limehouse to Leeds working class areas are “TAINTED LOVE” MASOOD KHAN, 41, a senior British Transport being invaded by yuppies, amenities sold off for Police inspector responsible for passenger safety across southeast England, has admitted meeting peanuts and communities ripped apart. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 Labour History Archive and Study Centre: Labour Party National Executive Committee Minutes, 1 March 1934. 2 See N. Copsey, Anti-Fascism in Britain (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 2000), p. 76. 3 See J. Bean, Many Shades of Black: Inside Britain’s Far Right (London: New Millennium, 1999). 4 See Searchlight, no. 128, Feb. 1986, p. 15. 5 See for example, C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’, New Community, vol. 20, no. 4 (1994), pp. 563–79. 6 For discussion of legitimacy as a social-scientific concept, see D. Beetham, The Legitimation of Power (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1991). 7 For earlier work on the BNP by this author, see N. Copsey, ‘Fascism: The Ideology of the British National Party’, Politics, vol. 14, no. 3 (1994), pp. 101–8 and ‘Contemporary Fascism in the Local Arena: The British National Party and “Rights for Whites”’, in M. Cronin (ed.) The Failure of British Fascism: The Far Right and the Fight for Political Recognition (Basingstoke: Macmillan- Palgrave, 1996), pp. 118–40. For earlier work by others, see for example C.T. Husbands, ‘Following the “Continental Model”?: Implications of the Recent Electoral Performance of the British National Party’; R. Eatwell, ‘Britain: The BNP and the Problem of Legitimacy’, in H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds), The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Estab- lished Democracies (Basingstoke: Macmillan-Palgrave, 1998), pp. 143–55; and D. Renton, ‘Examining the Success of the British National Party, 1999–2003’, Race and Class, vol. -

European Parliament Information Office in the Uk Media Guide 2011

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT INFORMATION OFFICE IN THE UK MEDIA GUIDE 2011 www.europarl.org.uk 2011 01 02 03 52 1 2 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 12 13 1 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 7 14 21 28 2 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 1 8 15 22 29 3 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 2 9 16 23 30 4 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 3 10 17 24 31 5 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 4 11 18 25 6 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 5 12 19 26 7 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 6 13 20 27 04 05 06 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 22 23 24 25 26 1 4 11 18 25 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 2 5 12 19 26 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 3 6 13 20 27 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 4 7 14 21 28 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 5 1 8 15 22 29 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 6 2 9 16 23 30 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 7 3 10 17 24 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 07 08 09 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 35 36 37 38 39 1 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 2 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 3 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 4 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 5 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 6 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 7 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 10 11 12 39 40 41 42 43 44 44 45 46 47 48 48 49 50 51 52 1 3 10 17 24 31 7 14 21 28 5 12 19 26 2 4 11 18 25 1 8 15 22 29 6 13 20 27 3 5 12 19 26 2 9 16 23 30 7 14 21 28 4 6 13 20 27 3 10 17 24 1 8 15 22 29 5 7 14 21 28 4 11 18 25 2 9 16 23 30 6 1 8 15 22 29 5 12 19 26 3 10 17 24 31 7 2 9 16 23 30 6 13 20 27 4 11 18 25 Неделя / Domingo / Nedĕle / Søndag / Sonntag / pühapäev / Κυριακή / Sunday / Dimanche / Domhnach / Domenica / svētdiena / sekmadienis / 7 Vasárnap / II-Ħadd / Zondag / Niedziela / Domingo / duminică / nedeľa / nedelja -

Nazis and the Far Right Today

NAZIS AND THE FAR RIGHT TODAY Compiled by Campbell M Gold (2010) CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- American Nazi Party (1959 - 1967) - USA The American Nazi Party was an American Neo-Nazi political party formed in February 1959 by George Lincoln Rockwell. The organization was headquartered in Arlington, Virginia and maintained a visitor's centre at 2507 North Franklin Road (now a coffeehouse). The organization was based largely upon the ideals and policies of the NSDAP in Germany during the Third Reich. Following the assassination of Rockwell in 1967 by a disgruntled party member, the group was taken over by Matt Koehl who renamed it the National Socialist White People's Party. --()-- National Socialist White People's Party (1967 - ?) - USA The National Socialist White People's Party was originally founded in 1958 by the late U.S. Navy Commander George Lincoln Rockwell (1918-1967) as the American Nazi Party. The name was changed to the National Socialist White People's Party in 1967, in order to better reflect the true nature and purpose of the organization. Commander Rockwell's subsequent assassination in August of that year led to a lengthy period of confusion and dormancy for the Party, but in the 1990's it has revived and is gaining ground steadily in numbers and influence among racially conscious White Americans. --()-- National Socialist Party of America (1970 - Date (2010)) The National Socialist Party of America was an extremist Chicago-based organization founded in 1970 by Frank Collin shortly after he left the National Socialist White People's Party. The NSWPP had been the American Nazi Party until shortly after the assassination of leader George Lincoln Rockwell in 1967. -

Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media

JASON LEE Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Nazism and Neo-Nazism in Film and Media Jason Lee Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Girl Scout confronts neo-Nazi at Czech rally. Photo: Vladimir Cicmanec Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 936 2 e-isbn 978 90 4852 829 5 doi 10.5117/9789089649362 nur 670 © J. Lee / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Acknowledgements 7 1. Introduction – Beliefs, Boundaries, Culture 9 Background and Context 9 Football Hooligans 19 American Separatists 25 2. Film and Television 39 Memory and Representation 39 Childhood and Adolescence 60 X-Television 66 Conclusions 71 3. Nazism, Neo-Nazism, and Comedy 75 Conclusions – Comedy and Politics 85 4. Necrospectives and Media Transformations 89 Myth and History 89 Until the Next Event 100 Trump and the Rise of the Right 107 Conclusions 116 5. Globalization 119 Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America 119 International Nazi Hunters 131 Video Games and Conclusions 135 6. Conclusions – The Infinitely Other 141 Evil and Violence 141 Denial and Memorial 152 Europe’s New Far Right and Conclusions 171 Notes 189 Bibliography 193 Index 199 Acknowledgements A special thank you to Stuart Price, Chair of the Media Discourse Group at De Montfort University (DMU).