Americans in Athens: Learning from Documenta 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

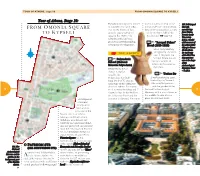

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January 2015

CURRICULUM VITAE Dimitris Papageorgiou Professor Department of Cultural Technology and Communication University of the Aegean January 2015 1 Table of Contents RESEARCH INTERESTS 3 ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS 3 TEACHNING EXPERIENCE AND EDUCATIONAL WORK 5 Α) Coordinator of the Social and Cultural Communication and Documentation Lab, 5 University of the Aegean Β) Tutor (on a contract) and then an elected member of the Academic and Scientific 6 Staff of the University of the Aegean 1) Undergraduate level 6 2) Postgraduate level 6 3) Supervision of doctoral theses 7 C) Other educational activities 8 D) Open Lectures & Presentations 9 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES 10 A) As a Researcher 10 B) As Coordinator of the Social and Cultural Communication and Documentation Lab, 12 University of the Aegean C) As Director and Scientific Responsible of the institutionalized Sound, Image and 14 Cultural Representation Lab of the Department of Cultural Technology and Communication C1) Co-funded Research Projects 14 C2) Funded Research Projects 27 PUBLICATIONS 29 A) PhD thesis 29 B) Books 29 B1) Monographs 29 B2) Editing of collective volumes 30 B3) Co-editing of collective volumes 31 C) Chapters in Greek books 32 D) Chapters in English/foreign language books 38 E) Articles in journals (reviewed) 40 PAPERS PRESENTATED AT CONFERENCES 44 A) Papers Presented at Greek Conferences 44 B) Papers Presented at International Conferences 48 PUBLICATIONS IN PROCEEDINGS OF GREEK CONFERENCES 63 PUBLICATIONS IN PROCEEDINGS OF INTERNATIONAL 63 CONFERENCES ADDITIONAL PUBLICATIONS 66 DOCUMENTARY -

46Haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·2 46Haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·3

46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·2 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·3 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 46th INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR YOUNG PARTICIPANTS 19 JUNE – 3 JULY 2006 PROCEEDINGS ANCIENT OLYMPIA 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·4 The commemorative seal of the Session. Published by the International Olympic Academy and the International Olympic Committee 2007 International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue 152 33 Halandri – Athens GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6878809-13, +30 210 6878888 Fax: +30 210 6878840 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ioa.org.gr Editor Assoc. Prof. Konstantinos Georgiadis, IOA Honorary Dean Photographs Giorgos Spiliopoulos Production: Livani Publishing Organization ISBN: 978-960-14-1716-5 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·5 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY FOURTY-SIXTH INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR YOUNG PARTICIPANTS SPECIAL SUBJECT: SPORT AND ETHICS ANCIENT OLYMPIA 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·6 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·7 ∂PHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2006) President ªinos X. KYRIAKOU Vice-President πsidoros ∫√UVELOS ªembers Lambis V. NIKOLAOU (IOC Vice-President) ∂mmanuel ∫ATSIADAKIS ∞ntonios ¡IKOLOPOULOS ∂vangelos SOUFLERIS Panagiotis ∫ONDOS Leonidas VAROUXIS Georgios FOTINOPOULOS Honorary President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH Honorary Vice-President ¡ikolaos YALOURIS Honorary Dean ∫onstantinos GEORGIADIS 7 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·8 46haggliko002s024 10-06-09 12:12 ™ÂÏ›‰·9 HELLENIC OLYMPIC COMMITTEE (2006) President Minos X. KYRIAKOU 1st Vice-President Isidoros KOUVELOS 2nd Vice-President Spyros ZANNIAS Secretary General Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS Δreasurer Pavlos KANELLAKIS Deputy Secretary General Antonios NIKOLOPOULOS Deputy Treasurer Ioannis KARRAS IOC Member ex-officio Lambis V. -

Fulltext Thesis (1.293Mb)

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, GALWAY European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation A.Y. 2015/2016 „As long as we are visible“ Refugees, Rights and Political Community Author: Jana Loew Supervisor: Ekaterina Yahyaoui Krivenko 1 Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Yorgos for his help in finding interview partners, many coffees and the interesting discussions on the way, those who were kind enough to take the time to speak to me, and the many things I learned from them, Ekaterina for her guidance, Brian, Mandy, Dan and Brenton for proofreading and motivation. 1 „as long as we are visible“ Larry (see annex 12) 1 Abstract In the year of 2015, due mainly to unrest in the Middle East, more refugees arrived in Europe than ever before. They have been met with national and EU policies that emphasise border control and deterrence rather than human rights and dignity. I argue here that the human rights regime has proven to be insufficient to ensure refugees’ rights are protected, owing to the inherent contradictions of sovereignty, citizenship, and universal rights by referring in particular to Arendt’s description of the complete rightlessness of refugees. However, drawing on field research and interviews in Athens and Hamburg, this thesis counters the description of refugees as passive and essentially non-political, showing that refugees in fact constitute themselves as political subjects. They do this in small ways through place-making and inserting themselves into the social fabric of everyday life, as well as more through more overtly political acts. By insisting on being seen and heard, they disrupt the mainstream discourse and framing of social reality. -

Why We Set Your Nights on Fire

Why we set your nights on fi re Communiques of greek nihilists (Conspiracy of Cells of Fire) Content Communique on the arson against the french press agency (Athens, 3/12/2008) Notes of the editors (Page 4) While the peaceful citizens where enjoying the coffee break of their in- existance in the paved street of Kolonaki, we set ourselves for once again un- This is how it is… if that‘s what you think… der the „services“ of destruction and prepared a new gift out of idyllic ashes. (Page 5) With these, we send our revolutionary greetings to the French comrades that selected to attack the network of the high speed trains, sabotaging the routes „... And death will no longer have any power ...“ of everyday hurry and anxiety, of a determined pre-set life imposed by the bio- (Page 11) authority to its subjects. Striking at the ordinary fl aw of the system, using aggresive means in the Declaration for the 1st November letter-bombing midst of the servitude suggested by the social actuality, for once again proving against European State targets in vivo the vulnerable structure of the fortifi ed uniformity of this world. We (Page 19) despise the cowardice of the crowds that is so welcome within this enslaved society and strive to point that society exists for us and not the opposite. Communique for the 12-13 January arson barrage in Thessaloniki, Greece Thus we will invade repeatedly and suddenly, eroding and poisoning its inner (Page 31) core, in order to eliminate everything that isn‘t us, by our very selves. -

Athens Constituted the Cradle of Western Civilisation

GREECE thens, having been inhabited since the Neolithic age, is considered Europe’s historical capital. During its long, Aeverlasting and fascinating history the city reached its zenith in the 5th century B.C (the “Golden Age of Pericles”), when its values and civilisation acquired a universal significance and glory. Political thought, theatre, the arts, philosophy, science, architecture, among other forms of intellectual thought, reached an epic acme, in a period of intellectual consummation unique in world history. Therefore, Athens constituted the cradle of western civilisation. A host of Greek words and ideas, such as democracy, harmony, music, mathematics, art, gastronomy, architecture, logic, Eros, eu- phoria and many others, enriched a multitude of lan- guages, and inspired civilisations. Over the years, a multitude of conque - rors occupied the city and erected splendid monuments of great signifi- cance, thus creating a rare historical palimpsest. Driven by the echo of its classical past, in 1834 the city became the capital of the modern Greek state. During the two centuries that elapsed however, it developed into an attractive, modern metropolis with unrivalled charm and great interest. Today, it offers visitors a unique experience. A “journey” in its 6,000-year history, including the chance to see renowned monu- ments and masterpieces of art of the antiquity and the Middle Ages, and the architectural heritage of the 19th and 20th cen- turies. You get an uplifting, embracing feeling in the brilliant light of the attic sky, surveying the charming landscape in the environs of the city (the indented coastline, beaches and mountains), and enjoying the modern infrastructure of the city and unique verve of the Athenians. -

Patterns of Contentious Politics Concentration

The London School of Economics and Political Science Patterns of contentious politics concentration as a ‘spatial contract’; a spatio-temporal study of urban riots and violent protest in the neighbourhood of Exarcheia, Athens, Greece (1974-2011) Antonios Vradis A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, December 2012. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 70,472 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I hereby state that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Douglas Michael Massing and Ailsa Campbell. ESRC PhD funding is hereby gratefully acknowledged (reference number: ES/F02214X/1). Abstract Existing studies of urban riots, violent protest and other instances of contentious politics in urban settings have largely tended to be either event- or time-specific in their scope. -

ECRE Urgently Calls on the EU and Member States for More Robust Solidarity As the Refugee Crisis in Greece Deepens

ECRE urgently calls on the EU and Member States for more robust solidarity as the refugee crisis in Greece deepens The current exceptional situation in Greece requires additional measures by the European Union and EU Member States to further support the initiatives taken by the Greek authorities and civil society organisations to address the increasing numbers of refugees arriving in Greece (for an overview of the current situation, please see the synopsis at the end of this call). In particular at the EU level, immediate and substantial efforts are needed to address the current situation in Greece through three types of concrete action: An immediate and substantial increase in emergency support to those assisting newly arriving refugees More financial and technical support is needed for the relentless efforts of the many volunteers, local organisations and NGOs in Greece, who are working under very difficult conditions and whose resources and capacity are already stretched. In addition to the first basic needs in terms of access to accommodation, nutrition and health care, there is a need to increase the provision of accurate information and access to legal assistance and counselling for the newly arriving refugees. This would allow refugees who may wish to enter the asylum procedure in Greece to gain effective access thereto. Additional funding is needed to strengthen the capacity of Greek NGOs specialised in the area of asylum and migration to provide such services, particularly on entry points including Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Kos and Leros and where relevant with the support of NGOs in other European countries. Continued support for the provision of reception conditions and legal assistance and information to refugees arriving in Athens and Thessaloniki is also needed. -

Athens • Attica Athens

FREE COPY ATHENS • ATTICA ATHENS MINISTRY OF TOURISM GREEK NATIONAL TOURISM ORGANISATION www.visitgreece.gr ATHENS • ATTICA ATHENS • ATTICA CONTENTS Introduction 4 Tour of Athens, stage 1: Antiquities in Athens 6 Tour of Athens, stage 2: Byzantine Monuments in Athens 20 Tour of Athens, stage 3: Ottoman Monuments in Athens 24 The Architecture of Modern Athens 26 Tour of Athens, stage 4: Historic Centre (1) 28 Tour of Athens, stage 5: Historic Centre (2) 37 Tour of Athens, stage 6: Historic Centre (3) 41 Tour of Athens, stage 7: Kolonaki, the Rigillis area, Metz 44 Tour of Athens, stage 8: From Lycabettus Hill to Strefi Hill 52 Tour of Athens, stage 9: 3 From Syntagma sq. to Omonia sq. 56 Tour of Athens, stage 10: From Omonia sq. to Kypseli 62 Tour of Athens, stage 11: Historical walk 66 Suburbs 72 Museums 75 Day Trips in Attica 88 Shopping in Athens 109 Fun-time for kids 111 Night Life 113 Greek Cuisine and Wine 114 Information 118 Michalis Panayotakis, 6,5 years old. The artwork on the cover is courtesy of the Museum of Greek Children’s Art. Maps 128 ATTICA • ATHENS Athens, having been inhabited since the Neolithic age, Driven by the echo of its classical past, in 1834 the is considered Europe’s historical capital and one of the city became the capital of the modern Greek state. world’s emblematic cities. During its long, everlasting During the two centuries that elapsed however, it and fascinating history the city reached its zenith in the developed into an attractive, modern metropolis with 5th century B.C (the “Golden Age of Pericles”), when its unrivalled charm and great interest. -

CITY BREAK Athens

CITY BREAK Athens www.visitgreece.gr So old yet so modern The Greek capital is a city that has it all; a vibrant cosmopolitan hub with a rich culture, a long history, and a mild climate; one that possesses an unfading allure, attracting tourists from all over the world and promising a memorable stay whether as a short break or a longer trip. Enjoy Athens’ high standard hotel services and facilities, and make the most of the wide range of choice you have as regards recreation, nightlife, shopping and dining. Use the modern metro, tram and railway system to reach most destinations. Walk along the promenade by the foot of the Acropolis, visit the city The Athenian Riviera Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre The Acropolis Museum centre and its traditional neighbourhoods, the museums, the ancient sites and monuments, the theatres and art galleries, but save some of your time for the suburbs as well. The north suburbs are green and more spacious than other areas; you will find great restaurants, malls, nightclubs and sports facilities. Head south and follow the coastline, along the Athenian Riviera, discover the sunny shores of south Attica, visit historic sights, relax by the seaside, have a refreshing swim or practice your favourite water sport. The list of alternatives you have is a long one. Whether you travel for business or for pleasure, Athens is the perfect choice for mixing these two, any time of the year! Peireos Street The Academy of Athens A walk in ancient Athens Ancient Athens is one of Europe’s oldest cities, one with a continuous history whose beginnings can be traced some 5,000 years ago. -

Athens the New York Times

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps “In Your Pocket: A cheeky, well- written series of guidebooks.” ATHENS The New York Times April - May 2011 Greek Easter A survival guide Gardens & Parks Spring in the city N°18 - €2 inyourpocket.com \ CONTENTS T H E M O S T C H I C B O U T I Q U E - K I T O N - S A R T O R I A P A R T E N O P E A - A L D E N - J O O P ! - R E N E L E Z A R D - W I N D S O R - S A I N T A N D R E W S - S E R A P H I N - I N C O T E X - B I E L L A C O L L E Z I O N I M E N ' S & L A D I E S F A S H I O N : 1 4 K A N A R I S T R . K O L O N A K I / 1 0 6 7 4 A T H E N S / T E L . : 2 1 0 3 6 2 2 8 6 0 CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Gardens and Parks Spring in the city 14 Greek Easter A surnival guide 15 Culture & Events Posing under the Acropolis What’s on 16 Dining & Nightlife Where to stay Restaurants 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 Blooming flowers in Thissio athens.inyourpocket.com April - May 2011 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS A constant rise in living standards, was taken for granted by the Greek population for decades.