Ecri Report on Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom of Religion and Other Human Rights for Non-Muslim Minorities in Turkey and for the Muslim Minority in Thrace (Eastern Greece)

Doc. 11860 21 April 2009 Freedom of religion and other human rights for non-Muslim minorities in Turkey and for the Muslim minority in Thrace (Eastern Greece) Report Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Rapporteur: Mr Michel HUNAULT, France, European Democrat Group Summary In the opinion of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, Greece and Turkey should have all their citizens belonging to religious minorities treated in accordance with the provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, rather than rely on the “reciprocity” principle stated by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne to withhold the application of certain rights. The committee acknowledges that the question is “emotionally very highly charged”, but it asserts that the two countries should treat all their citizens without discrimination, regardless of the way in which the neighbouring state may treat its own citizens. The committee considers that the recurrent invoking by Greece and Turkey of the principle of reciprocity as a basis for refusing to implement the rights secured to the minorities concerned by the Treaty of Lausanne is “anachronistic” and could jeopardise each country's national cohesion. However, it welcomes some recent indications that the authorities of the two countries have gained a certain awareness, with a view to finding appropriate responses to the difficulties faced by the members of these minorities, and encourages them to continue their efforts in that direction. The committee therefore urges the two countries to take measures for the members of the religious minorities – particularly as regards education and the right to own property – and to ensure that the members of these minorities are no longer perceived as foreigners in their own country. -

2020 Issued by Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion Or Belief Purpose Preparation for the Report to the 46Th Session of Human Rights Council

Avrupa Batı Trakya Türk Federasyonu Föderation der West-Thrakien Türken in Europa Federation of Western Thrace Turks in Europe Ευρωπαϊκή Ομοσπονδία Τούρκων Δυτικής Θράκης Fédération des Turcs de Thrace Occidentale en Europe NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations Member of the Fundamental Rights Platform (FRP) of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Member of the Federal Union of European Nationalities (FUEN) Call for input: Report on Anti-Muslim Hatred and Discrimination Deadline 30 November 2020 Issued by Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief Purpose Preparation for the report to the 46th Session of Human Rights Council Submitted by: Name of the Organization: Federation of Western Thrace Turks in Europe (ABTTF) Main contact person(s): Mrs. Melek Kırmacı Arık E-mail: [email protected] 1. Please provide information on what you understand by the terms Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hatred; on the intersection between anti-Muslim hatred, racism and xenophobia and on the historical and modern contexts, including geopolitical, socio-and religious factors, of anti-Muslim hatred. There are numerous definitions of Islamophobia which are influenced by different theoretical approaches. The Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, which annualy publish European Islamophobia Report, uses the working definition of Islamophobia that theorizes Islamophobia as anti-Muslim racism. The Foundation notes that Islamophobia is about a dominant group of people aiming at seizing, stabilizing and widening their power by means of defining a scapegoat – real or invented – and excluding this scapegoat from the resources/rights/definition of a constructed ‘we’. -

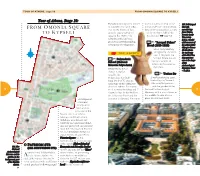

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Americans in Athens: Learning from Documenta 14

14 Essay Americans in Athens: learning Adrian Anagnost and from documenta 14 Manol Gueorguiev Authors: Adrian Anagnost and Manol Gueorguiev Erschienen in : all-over 14, Spring/Summer 2018 Publikationsdatum : 5. Juli 2018 URL : http://allover-magazin.com/?p=3150 ISSN 2235-1604 Quellennachweis : Adrian Anagnost and Manol Gueorguiev, Americans in Athens: learning from documenta 14, in : all-over 14, Spring Summer 2018, URL: http://allover-magazin.com/?p=3150 Abstract This essay offers a critical account of socially-engaged works by Verwendete Texte, Fotos und grafische Gestaltung sind United States artists at documenta in Athens, Greece, in 2017. urheberrechtlich geschützt. Eine kommerzielle Nutzung der Texte Focusing on William Pope.L’s Whispering Campaign and Rick Lowe’s und Abbildungen – auch auszugsweise – ist ohne die vorherige Victoria Square Project, this article examines the status of Greek schriftliche Genehmigung der Urheber oder Urheberinnen history for works by international artists and the challenges of trans- nicht erlaubt. Für den wissenschaftlichen Gebrauch der Inhalte planting long-running artistic strategies to new locations. It argues empfehlen wir, sich an die vorgeschlagene Zitationsweise that social practices face the same challenges of translation as artworks zu halten, mindestens müssen aber Autor oder Autorin, Titel des in other media, and that social practice is, ultimately, site specific. Aufsatzes, Titel des Magazins und Permalink des Aufsatzes angeführt werden. Keywords social practice, social sculpture, migration, Athens, documenta, © 2018 all-over | Magazin für Kunst und Ästhetik, Wien / Basel site specificity 14 Essay Americans in Athens: learning Adrian Anagnost and from documenta 14 Manol Gueorguiev A claim: Social practice is site specific. -

Religious Education in Greece - Orthodox Christianity, Islam and Secularism

ISSN 2411-9563 (Print) European Journal of Social Sciences September-December 2015 ISSN 2312-8429 (Online) Education and Research Volume 2, Issue 4 Religious Education in Greece - Orthodox Christianity, Islam and Secularism Marios Koukounaras Liagkis Lecturer in Religious Education, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens [email protected] Angeliki Ziaka Assistant Professor in the Study of Religion, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki [email protected] Abstract This study is an attempt to address the issue of religion in the public sphere and secularism. Since the Eastern Orthodox Church has been established by the Greek constitution (1975) as the prevailing religion of Greece, there are elements of legal agreements- which inevitably spawn interactions- between state and Church in different areas. One such area is Religious Education. This article focuses on Religious Education (RE) in Greece which is a compulsory school subject and on two important interventions that highlight the interplay between religion, politics and education: firstly the new Curriculum for RE (2011) and secondly the introduction of an Islamic RE (2014) in a Greek region (Thrace) where Christians and Muslims have lived together for more than four centuries. The researches are based on fieldwork research and they attempt to open the discussion on the role of RE in a secular education system and its potential for coexistence and social cohesion. Key words: religious education, secularism, curriculum, Islam, public sphere Introduction This article is focused -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

Genetic Characterization of Greek Population Isolates Reveals Strong Genetic Drift at Missense and Trait-Associated Variants

ARTICLE Received 22 Apr 2014 | Accepted 22 Sep 2014 | Published 6 Nov 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6345 OPEN Genetic characterization of Greek population isolates reveals strong genetic drift at missense and trait-associated variants Kalliope Panoutsopoulou1,*, Konstantinos Hatzikotoulas1,*, Dionysia Kiara Xifara2,3, Vincenza Colonna4, Aliki-Eleni Farmaki5, Graham R.S. Ritchie1,6, Lorraine Southam1,2, Arthur Gilly1, Ioanna Tachmazidou1, Segun Fatumo1,7,8, Angela Matchan1, Nigel W. Rayner1,2,9, Ioanna Ntalla5,10, Massimo Mezzavilla1,11, Yuan Chen1, Chrysoula Kiagiadaki12, Eleni Zengini13,14, Vasiliki Mamakou13,15, Antonis Athanasiadis16, Margarita Giannakopoulou17, Vassiliki-Eirini Kariakli5, Rebecca N. Nsubuga18, Alex Karabarinde18, Manjinder Sandhu1,8, Gil McVean2, Chris Tyler-Smith1, Emmanouil Tsafantakis12, Maria Karaleftheri16, Yali Xue1, George Dedoussis5 & Eleftheria Zeggini1 Isolated populations are emerging as a powerful study design in the search for low-frequency and rare variant associations with complex phenotypes. Here we genotype 2,296 samples from two isolated Greek populations, the Pomak villages (HELIC-Pomak) in the North of Greece and the Mylopotamos villages (HELIC-MANOLIS) in Crete. We compare their genomic characteristics to the general Greek population and establish them as genetic isolates. In the MANOLIS cohort, we observe an enrichment of missense variants among the variants that have drifted up in frequency by more than fivefold. In the Pomak cohort, we find novel associations at variants on chr11p15.4 showing large allele frequency increases (from 0.2% in the general Greek population to 4.6% in the isolate) with haematological traits, for example, with mean corpuscular volume (rs7116019, P ¼ 2.3 Â 10 À 26). We replicate this association in a second set of Pomak samples (combined P ¼ 2.0 Â 10 À 36). -

Curriculum Vitae

CHRISTOS N. KALFAS Dr. CIVIL ENGINEER - MATHEMATICIAN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR CIVIL ENGINEERING FACULTY, DEMOCRITUS UNIVERSITY OF THRACE CURRICULUM VITAE BIO STUDIES TEACHING, PROFESSIONAL AND RESEARCH WORK ANALYSIS OF SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS XANTHI, 2012 1 2 CONTENTS 1. Brief Curriculum Vitae 5 2. Foreign Languages 6 3. Teaching Experience 7 3.1 Graduate courses 7 3.2 Postgraduate courses 8 4. Doctoral Theses 8 5. Postgraduate Theses 10 6. Dissertations 10 7. Research Projects 10 8. Books – Notes 11 8.1 Books 11 8.2 Notes 12 9. Seminars - Lectures 12 10. Conferences 13 10.1 Participation in Conferences 13 10.2 Conference Organisation 14 10.3 Editing of Conference Proceedings 14 11. Participation in Societies 14 12. Participation in Committees 15 13. Participation in Committees for the selection of 15 Members of Teaching and Research Staff 14. Professional Work 15 14.1 Design of works 15 14.2 Propositions and Preliminary Designs for Various Projects 18 14.3 Technical Consultant for the Implementation of Projects 19 3 14.4 Expert Reports 19 15. List of Scientific Publications 19 15.1 Doctoral Thesis 19 15.2 Publications in International Magazines 19 15.3 Papers for Judged Conferences 20 15.4 Articles in Greek Magazines 26 16. Publication References 27 4 1. BRIEF CURRICULUM VITAE Surname : KALFAS Name : CHRISTOS Father’s Name : NIKOLAOS Place of Birth : Drama, Greece Date of Birth : 4 November 1947 Family Status : Married. Father to 2 boys, aged 20 and 24. 1953 - 1959 : Iliokomi Primary School, Prefecture of Serres 1959 - 1965 : 2nd Boys’ Secondary School of Thessaloniki 1965 -1970 : University studies in the Mathematics Dept. -

Ethnic Turks in Greece, a Muslim Minority

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels Phone/Fax: 32 2 3456145 Email: [email protected] – Website: http://www.hrwf.net Ethnic Turks in Greece, a Muslim Minority Preliminary Report By Willy Fautré Executive Summary Recommendations Introduction The Identity and Identification Issue Official Position of Greece on Issues Related to Ethnic Turks Mission of Human Rights Without Frontiers: Report and State of Play School Education of Minority Children in Turkish and in Greek Freedom of Association Freedom of Religion Freedom of the Turkish-Language Community Media Conclusion November 2012 Executive Summary In this report, Human Rights Without Frontiers (HRWF), an independent nongovernmental organisation, raises concerns for basic freedoms and human rights for the ethnic Turkish minority in Greece. In order to investigate these charges, HRWF participated in a fact-finding mission to Thrace from 16th to 20th October 2012. The findings of this mission are included in this report. Chapter 1 describes the historical background of identity issues for ethnic Turks in Thrace, who have lived in the region for centuries. After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, agreements made under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne sought to protect the cultural integrity of the ethnic Turkish community in terms of language, religion and culture; however, since the 1990s the Greek government has sought to promote a policy of national assimilation, even to the point of denying the existence of any such ethnic minorities within its borders. Turkish identity has been systematically suppressed in favour of a homogenised view of Greek society. The use of the term “Turkish minority” is thus officially banned in Greece. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January 2015

CURRICULUM VITAE Dimitris Papageorgiou Professor Department of Cultural Technology and Communication University of the Aegean January 2015 1 Table of Contents RESEARCH INTERESTS 3 ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS 3 TEACHNING EXPERIENCE AND EDUCATIONAL WORK 5 Α) Coordinator of the Social and Cultural Communication and Documentation Lab, 5 University of the Aegean Β) Tutor (on a contract) and then an elected member of the Academic and Scientific 6 Staff of the University of the Aegean 1) Undergraduate level 6 2) Postgraduate level 6 3) Supervision of doctoral theses 7 C) Other educational activities 8 D) Open Lectures & Presentations 9 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES 10 A) As a Researcher 10 B) As Coordinator of the Social and Cultural Communication and Documentation Lab, 12 University of the Aegean C) As Director and Scientific Responsible of the institutionalized Sound, Image and 14 Cultural Representation Lab of the Department of Cultural Technology and Communication C1) Co-funded Research Projects 14 C2) Funded Research Projects 27 PUBLICATIONS 29 A) PhD thesis 29 B) Books 29 B1) Monographs 29 B2) Editing of collective volumes 30 B3) Co-editing of collective volumes 31 C) Chapters in Greek books 32 D) Chapters in English/foreign language books 38 E) Articles in journals (reviewed) 40 PAPERS PRESENTATED AT CONFERENCES 44 A) Papers Presented at Greek Conferences 44 B) Papers Presented at International Conferences 48 PUBLICATIONS IN PROCEEDINGS OF GREEK CONFERENCES 63 PUBLICATIONS IN PROCEEDINGS OF INTERNATIONAL 63 CONFERENCES ADDITIONAL PUBLICATIONS 66 DOCUMENTARY -

Infrastructure in Greece Funding the Future

Infrastructure in Greece Funding the future March 2017 PwC Content overview 1 Executive 2 Infrastructure summary investment The investment gap in Greek 3 Greek 4 Funding of infrastructure infrastructure Greek projects infrastructure is around pipeline projects Conclusion 5 1.4pp of GDP Infrastructure March 2017 PwC 2 Executive Summary Funding the future • According to OECD, global infrastructure needs* are expected to increase along the years to around $ 41 trln by 2030 • In Greece, the infrastructure investments were affected by the deep economic recession. The infrastructure investment gap is between 0.8 pp of GDP (against the European average) or 1.4 pp of GDP (against historical performance) translating into 1.1% or € 2bln new spending per year • Infrastructure investments have an economic multiplier of 1.8x** which can boost demand of other sectors. The construction sector will be enhanced creating new employment opportunities on a regular basis, attracting foreign investors and improving economic growth • Greece is ranked 26th among the E.U. countries in terms of infrastructure quality, along with systematic low infrastructure quality countries, mostly in Southern Europe • Greek infrastructure backlog has grown enormously during the crisis. The value of 69 projects, which are in progress or upcoming is amounting to €21.4bln – 42% accounting for energy projects, while 46% coming from rail and motorway projects • Announced tourist infrastructure and waste management projects (latter are financed through PPPs), estimated at 13% of total pipeline budget, are key to development and improvement of quality of life • Between 2014-2017(February) 16 of the infrastructure projects have been completed • Traditional funding sources, such as loan facilities and Public Investments Program are becoming less sustainable over the years, shifting the financing focus to the private sector. -

The Egnatia Motorway

EX POST EVALUATION OF INVESTMENT PROJECTS CO-FINANCED BY THE EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND (ERDF) OR COHESION FUND (CF) IN THE PERIOD 1994-1999 THE EGNATIA MOTORWAY PREPARED BY: CSIL, CENTRE FOR INDUSTRIAL STUDIES, MILAN PREPARED FOR: EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL REGIONAL POLICY POLICY DEVELOPMENT EVALUATION MILAN, SEPTEMBER 5, 2012 This study is carried out by a team selected by the Evaluation Unit, DG Regional Policy, European Commission, through a call for tenders by open procedure no 2010.CE.16.B.AT.036. The consortium selected comprises CSIL – Centre for Industrial Studies (lead partner – Milan) and DKM Economic Consultants (Dublin). The Core Team comprises: - Scientific Director: Massimo Florio, CSIL and University of Milan; - Project Coordinators: Silvia Vignetti and Julie Pellegrin, CSIL; - External experts: Ginés de Rus (University of Las Palmas, Spain), Per-Olov Johansson (Stockholm School of Economics, Sweden) and Eduardo Ley (World Bank, Washington, D.C.); - Senior experts: Ugo Finzi, Mario Genco, Annette Hughes and Marcello Martinez; - Task managers: John Lawlor, Julie Pellegrin and Davide Sartori; - Project analysts: Emanuela Sirtori, Gelsomina Catalano and Rory Mc Monagle. A network of country experts provides the geographical coverage for the field analysis: Roland Blomeyer, Fernando Santos (Blomeyer and Sanz – Guadalajara), Andrea Moroni (CSIL – Milano), Antonis Moussios, Panos Liveris (Eurotec - Thessaloniki), Marta Sánchez-Borràs, Mateu Turró (CENIT – Barcelona), Ernestine Woelger (DKM – Dublin). The authors of this report are Gelsomina Catalano and Davide Sartori of CSIL who were also responsible for the field research. Useful research assistance has been provided by Chiara Pancotti and Stathis Karapanos. The authors are grateful for the very helpful comments from the EC staff and particularly to Veronica Gaffey, José-Luís Calvo de Celis and Kai Stryczynski.