The Inception of the Society Was A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Concerning the Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 Affaire Relative a L'incident Aérien Du 27 Juillet 195 5

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS CASE CONCERNING THE AERIAL INCIDENT OF 27 JULY 1955 (UNITED KINGDOM v. BULGARIA) OBDER OF 3 AUGUST 1959 COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRETS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES AFFAIRE RELATIVE A L'INCIDENT AÉRIEN DU 27 JUILLET 195 5 (ROYAUME-UNI C. BULGARIE) ORDONNANCE DU 3 AOÛT 1959 This Order should be cited as follows: "Case concerning the Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 (United Kingdom v. Bulgaria) , Order of 3 August 1959: I.C.J. Reports 19-59, p. 264." La présente ordonnance doit être citée comme suit: Afa.ire relative à l'incident aérien du 27 juillet 1955 (Royaume-Uni c. Bulgarie), Ordonnance dzt 3 août 1959: C. I. J. Recueil 1959, p. 264. » -- - -- Sales number NO de vente : 2'11 INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE 1959 YEAR 1959 3 Augus: General List: 3 August 1959 CASE CONCERNING THE AERIAL INCIDENT OF 27 JuLy 1911 (UNITED KINGDOM v. BULGARIA) ORDER The President of the International Court of Justice, having regard to Article 48 of the Statute of the Court and to Article 69 of the Rules of Court; Having regard to the Application, dated 19 November 1957 and filed in the Registry of the Court on 22 November 1957, by which the Govemment of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Nor- them Ireland instituted proceedings before the Court against the Govemment of the People's Republic of Bulgaria with regard to the losses sustained by citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies by reason of the destruction, on 27 July 1955, by the Bulgarian anti- aircraft defence forces, of an aircraft belonging to El Al Israel Airlines Ltd. -

Department of Finance and Administration Correspondence 1959-1962

DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATION CORRESPONDENCE 1959-1962 RECORD GROUP 272 by Ted Guillaum Archival Technical Services Tennessee State Library & Archives Date Completed: September 28,1999 MICROFILM ONLY INTRODUCTION Record Group 272, Department of Finance and Administration, Correspondence, spans the years 1959 through 1962 with the majority of the records focusing on the years 1959 through 1961. The correspondence of two commissioners of the Department of Finance and Administration is represented in this collection. The commissioners were Edward J. Boling and Harlan Mathews. Edward J. Boling served from February, 1959 through August, 1961. Harlan Mathews was appointed commissioner in September of 1961. These records reflect the various activities connected with the administration of financial and budgetary matters of the Executive branch. Original order was maintained during processing. These records were transferred to the archives in good condition in 1983. The original size of the collection was about eight cubic feet but was reduced to seven cubic feet by the elimination of duplicate copies and extraneous material. The collection was microfilmed and all documents were destroyed. There are no restrictions to access. SCOPE AND CONTENT Record Group 272, Department of Finance and Administration, Correspondence, spans the period 1959 through 1962, although the bulk of the collection is concentrated within the period 1959 through 1961. The collection consists of seven cubic feet of material that has been microfilmed and the originals were destroyed. The original order of this collection was maintained during processing. The arrangement of this collection is chronological for the period of 1959 through 1960. The remainder of the collection is chronological, then alphabetical by topics. -

Alain Locke Faith and Philosophy

STUDIES IN THE BÁBÍ AND Bahá’í Religions Volume Eighteen Alain Locke Faith and Philosophy Studies in the Bábí and Bahá’í Religions (formerly Studies in Bábí and Bahá’í History) ANTHONY A. LEE, General Editor Studies in Bábí and Bahá’í History, Volume One, edited by Moojan Momen (1982). From Iran East and West, Volume Two, edited by Juan R. Cole and Moojan Momen (1984). In Iran, Volume Three, edited by Peter Smith (1986). Music, Devotions and Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, Volume Four, by R. Jackson Armstrong-Ingram (1987). Studies in Honor of the Late H. M. Balyuzi, Volume Five, edited by Moojan Momen (1989). Community Histories, Volume Six, edited by Richard Hollinger (1992). Symbol and Secret: Qur’an Commentary in Bahá’u’lláh’s Kitáb-i Íqán, Volume Seven, by Christopher Buck (1995). Revisioning the Sacred: New Perspectives on a Bahá’í Theology, Volume Eight, edited by Jack McLean (1997). Modernity and the Millennium: The Genesis of the Baha’i Faith in the Nineteenth-Century Middle East, distributed as Volume Nine, by Juan R. I. Cole, Columbia University Press (1999). Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Bahá’í Faith, distributed as Volume Ten, by Christopher Buck, State University of New York Press (1999). Religion in Iran: From Zoroaster to Bahau’llah, distributed as Volume Eleven, by Alessandro Bausani, Bibliotheca Persica Press (2000). Evolution and Bahá’í Belief: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Response to Nineteenth-Century Darwinism, Volume Twelve, edited by Keven Brown (2001). Reason and Revelation, Volume Thirteen, edited by Seena Fazel and John Danesh (2002). -

KENTUCKY in AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I by JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND

KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I BY JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS JOHN FILSON John Filson, the first Kentucky historian, was born at East Fallowfield, Pennsylvania, in 1747. He was educated at the academy of the Rev. Samuel Finley, at Nottingham, Maryland. Finley was afterwards president of Princeton University. John Filson looked askance at the Revolutionary War, and came out to Kentucky about 1783. In Lexington he conducted a school for a year, and spent his leisure hours in collecting data for a history of Kentucky. He interviewed Daniel Boone, Levi Todd, James Harrod, and many other Kentucky pioneers; and the information they gave him was united with his own observations, forming the material for his book. Filson did not remain in Kentucky much over a year for, in 1784, he went to Wilmington, Delaware, and persuaded James Adams, the town's chief printer, to issue his manuscript as The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke; and then he continued his journey to Philadelphia, where his map of the three original counties of Kentucky—Jefferson, Fayette, and Lincoln— was printed and dedicated to General Washington and the United States Congress. This Wilmington edition of Filson's history is far and away the most famous history of Kentucky ever published. Though it contained but 118 pages, one of the six extant copies recently fetched the fabulous sum of $1,250—the highest price ever paid for a Kentucky book. The little work was divided into two parts, the first part being devoted to the history of the country, and the second part was the first biography of Daniel Boone ever published. -

Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints

De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers 415 7th Street S. E., Washington, DC 20003 [email protected] (202) 578-4803 List 30, New Series Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints 19th C. American Paper ⸙ African Americana, Banking, Masons, Medical Americana, Steam Navigation, Temperance & U. S. Election History, De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers MANUSCRIPT LETTER WRITTEN FOR PUBLICATION ATTACKING J. Q. ADAMS AND PRAISING HENRY CLAY 1. (Adams, John Quincy) Open Letter Sent to the Philadelphia Newspaper, The American Sentinel, addressed “To John Q. Adams, President of the United States, & signed Lysimachus”. ca. 1828. $ 750.00 Two folio sheets of manuscript. 325 x 220 mm., [12 ¾ x 8 inches]. 4 pp., approximately 1500 words of text, written in ink in a mostly legible hand. Letter previously folded with minor tears to edges. Autograph Letter Signed with a pseudonym “Lysimachus”, known in history as a revered bodyguard of Alexander the Great. At the very top of the first leaf the words “For the A S” are written and believed to mean American Sentinel. Written by a partisan defender of Henry Clay, the author castigates John Quincy Adams for using his power to hire only those “whom you are indebted for your election. those that support you are the old hangers on.” I have been amongst the slaves, the very serfs from Europe. I have witnessed their drunken _____? and mock election but have never seen a man more perfectly worshipped and more obediently served than yourself. The slaves that now uphold you be assured will not continue their support when it most will be needed. Their obligation will terminate with your downfall. -

Index to Volume 3

Index to Volume 3 OHIO VALLEY HISTORY 2003 Apelt, Brian, The Corporation: A Centennial Biography of A United States Steel Corporation, 1901 -2001, (3) 79 81 Appaiachia, 11) 31-43 Abington School District u. Schempp, (3)34 Appalachia: A History, John Alexander Williams, (3) A & I Wolf and Co, (1)2 77-78 abolitionism, (1)6-12, 14; Old Line abolitionism, (1) 10 Appalachian Committee for Full Employment (ACFE), (1) abolitionists, (1)3-4, (2)3, 10, 12 37,38 activism, grass-roots, (1)31-43; social, (1)31 Appalachian Mountains, (4)4, 13 Adams, James, (2) 11 App&&an Regional Commission (ARC), (1)34 Adams, John, (4)26 Appalachian Volunteers (Avs), (1) 39 Adams, John Quincy, (3) 63 Appleby, Monica, (4) 62 Adams, Luther, (3) 37 apprentices, acts concernifig, (1) 11 Adjutant General of Georgia, (4) 48 Area Development Administration of the Department of adultery, (4) 6-7 Commerce, (1)39,41 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2) 13 Armed Forces, (3) 44 African Americarls, (1) 3-4, 7-8, 26, (2) 3-15, 31-43, 50, (7) Army of the Ohio, (4)47 37-50, (4) 38-39; as slaves, (2) 3-15; as fugitive slave, Army of the West, (4) 13 3-8; and cxodus from Cincirinati, (2) 8; and Art as Image: Prints and Promotion in Cincinnati, Ohio, Underground Railroad, (2) 12; women, (2)13; Alice Cornell, ed., (3)74-76 Cincinnatians, (2) 13; as solcliers, (2)35,37-39; and artiller~: (4) 40 religion, (2)31-32; conversions, (2)32, 35; and artisans, German-born, (1)19 Christianity, (2)38; and chuickes, \I\$0; as Ba@h, Ashendel, Anita, (1)1-2, 17 (2)42; migrants, (3) 37-50; conception of South, (3) Athenaeum, (3) 20 3 7; and their neighborhoods, (3)39; racial Atlanta, Georgia, (3)43 discrimination of, (3) 40; and employment, (3) 45; Attorney General, (4) 29-30 and civil fights movement, (1)42, (3)47-48 auctions, land, (4) 25-27 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2)40,42 Austin, Stephen, (3)53 Afro-Christianity, (2) 3 1 hyddort, Dr. -

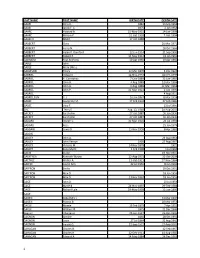

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

LAST NAME FIRST NAME BIRTH DATE DEATH DATE GAAEI Dora K

LAST NAME FIRST NAME BIRTH DATE DEATH DATE GAAEI Dora K. 1882 13 Sep 1968 GAAEI Jacob F. C. 1875 2 Jan 1958 GAARE Howard A. 15-May-1915 14-Jan-1998 GAARE Miriam K. 31-Oct-1918 7-Oct-1994 GAASCH Albert 17 Oct 1888 GABBERT Clara 20 Mar 1971 GABBERT Harry N. 18 Oct 1966 GABBERT Helen P. Rumford 12 Jun 1914 21 Sep 1992 GABBERT Robert E. 11 May 1912 24 Jan 1991 GABHARD Paul Anthony 10 Apr 1960 10 Apr 1960 GABLE John GABLE Mary (Mrs.) GABLESON Henry 12 Mar 1870 6 Dec 1924 GABRIEL Edward 12-Nov-1937 April 9, 1995 GABRIEL H. Constance 7-Dec-1889 31-Jan-1985 GABRIEL John A. 4 Aug 1889 12 Mar 1968 GABRIEL John A. 4-Aug-1889 12-Mar-1968 GABRIEL John P. 31-Mar-1923 2-Jun-1993 GABRIEL 4 Aug 1911 GABRIELSON H. J. 10 Jan 1867 8 Mar 1918 GABSE Josephine M. 17 Feb 1904 27 Feb 1980 GABSE Otto F. 23 Jul 1960 GAC Terry S. Aug. 12, 1948 24-Aug-2003 GACKEY Sarah Ann 27 Oct 1887 30 Jan 1930 GACKEY Sarah Ann 27 Oct 1887 30 Jan 1930 GADARD Joseph C. 30-Mar-1901 26-Jul-1994 GADARD Rose 25 Jan 1979 GADBAW Lewis B. 15 Nov 1909 8 Apr 1982 GADDIS GADLEY John A. 24 Aug 1964 GADLEY John Vernon 1950 27 Aug 1967 GADLEY Victoria M. 24 Nov 1878 1921 GADLEY Zona Myrle 2 Feb 1908 1 Jul 1994 GAENI Crape 19 Nov 1907 GAERTNER Kenneth Wayne 22-Aug-1931 31-Oct-2009 GAETHLE Walter A. -

Fall-2003.Pdf

OHIO ALLEY EDITORIAL BOARD HIS'/ORY · STAFF Compton Allyn Christine 1..Heyrman joseph R Reidy Cincimiati Museum Center Editors University of Delaware Howard University History Advisory Board Wayne K. Durrill J. Blaine Hudson Steven J. Ross Christopher Phillips Stephen Aron University of 1 ouisuille University of ilitbern Department of History University of Califoynia Califwma R. Douglas Hurt University of Cincinnati al Los Angeles Iowa State University Harry N. Scheiber Joan E. Cashin University of Calif,) Managing Editors James C. Klotter rnia Obio State Umversity Berkeley Jennifer Reiss Georgetown College at The Filson Historical Society Andrew R. L. Cayton Steven M. S[o,ve Bruce I.evine Mioinj University indiana Uliwer:ity Ruby Rogers University of California Cincinnati Museum Center R. David Edmunds at Santa Ci·Hz Roger D. Tate University of Texas at Dallas Somerset Commitility Editon'at Assistant Zane L. Miller College Kelly Wright Ellen T. Eslinger Ultiversit,of Cincinnati DePatil Uiliversity Joe W.Trotter,Jr. Department of History Elizabeth A. Perkins University of Cilicilinati Caniegie Mellon University Craig T Friend Centre College University of Central Florida Altina Waller A. Ramage James University of Connecticut Northern Kentucky U,iiversity C]NCINNATI MUSEUM CENTER THE F[i.SON HIS7'ORICAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES SOC[ETY BOAR!)01: DIRECTORS Cbair Helen Black Robert E Kistinger President H. C. Buck Niehoff David Bohi Laura Long Dr. R. Ted Steinbock Ronald D. Brown Steven R. Love Past Chair Vice-President Otto M. Budig,Jr. Craig Maier Valerie L. Newell Emily S. Bingham Brian Carley Shenan R Murphy Chairs Vice Richard 0. Coleman Robert Olson Secretary-Treasurer Ken Lowe Bob Coughlin Scott Robertson Henry Ormsby Greg Kenny Diane L. -

Early Literary Magazines in Kentucky, 1800-1900 Robert M

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School Summer 1934 Early Literary Magazines in Kentucky, 1800-1900 Robert M. Ferry Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Ferry, Robert M., "Early Literary Magazines in Kentucky, 1800-1900" (1934). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 2401. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/2401 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITJiJRARY J\1fAGAznms nr ICE:UTUCKY, 1800-1900 55#1 0 0 ·1 SID3MITT1tJD PARTIAL FULFILUIBUT OF THE REQPIR.EMEUTS FOR DEGREE OF ][ASTER OF KENTUCKY STATE COLLEGE AUGUST, 1934 Approved: ... Jill.a j or Pro fess or and Department of English History Graduate Committee iv r:wrHODUCTION V CHAPTlTIR I THE====~~ 1 , FIONTI:ER JOURNALIST 7 ~::'~~.:;.:;.!.:. AND 28 IV 41 V 5? 66 PREFACE This study of the literary magazines published in Kentucky between 1800 and 1900 consists of material derived from. the following sources: The Louisville Public Library; ti1e and Kentucky Sta.te Historical Society libraries, ]'rankfort; the Lexington Public Li.brary, Transylvania, and University of ntucky li.braries, Lexington; the public libraries of .Faris, Covington, Newport, Cincinnati, and Nashville; the stern Kentucky State Teachers College library, Bowling Green; and also the newspaper files of the Nashville Banner, the Lexington Herald, the Paris Kentuckian-Citizen, and the Courier-,Tournal. I wish to thank Dr. -

Views and Experiences from a Colonial Past to Their Unfamiliar New Surroundings

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Matthew David Smith Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ Director Dr. Carla Gardina Pestana _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Andrew R.L. Cayton _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Mary Kupiec Cayton ____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Katharine Gillespie ____________________________________________ Dr. Peter Williams Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT "IN THE LAND OF CANAAN:" RELIGIOUS REVIVAL AND REPUBLICAN POLITICS IN EARLY KENTUCKY by Matthew Smith Against the tumult of the American Revolution, the first white settlers in the Ohio Valley imported their religious worldviews and experiences from a colonial past to their unfamiliar new surroundings. Within a generation, they witnessed the Great Revival (circa 1797-1805), a dramatic mass revelation of religion, converting thousands of worshipers to spiritual rebirth while transforming the region's cultural identity. This study focuses on the lives and careers of three prominent Kentucky settlers: Christian revivalists James McGready and Barton Warren Stone, and pioneering newspaper editor John Bradford. All three men occupy points on a religious spectrum, ranging from the secular public faith of civil religion, to the apocalyptic sectarianism of the Great Revival, yet they also overlap in unexpected ways. This study explores how the evangelicalism -

NSC Series, Subject Subseries

WHITE HOUSE OFFICE, OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS: Records, 1952-61 NSC Series, Subject Subseries CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Arms Control, U.S. Policy on [1960] Atomic Energy-The President [May 1953-March 1956] (1)(2) [material re the function of the special NSC committee to advise the President on use of atomic weapons] Atomic Weapons, Presidential Approval and Instructions for use of [1959-1960] (1)- (5) Atomic Weapons, Correspondence and Background for Presidential Approval and Instructions for use of [1953-1960] (1)-(6) Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (1) [1953-1954] [nuclear powered aircraft; Nevada atomic weapons tests; Department of Defense participation in the weapons program] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (2) [1952-54] [custody of atomic weapons] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (3) [1953-54] [transfer and deployment of nuclear weapons; operation TEAPOT] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (4) [1953-54] [safety tests; weapons program; development of fuel elements for nuclear reactors] Atomic Weapons and Classified Intelligence-Misc. (1) [1955-1957] [test moratorium on nuclear weapons; development of a high yield weapon] Atomic weapons and Classified Intelligence-Misc. (2) [1954-1960] [disclosures of classified intelligence; downgrading, declassification and publication of NSC papers] 2 Base Rights [November 1957-November 1960] (1)-(4) [U.S. overseas military bases] Study of Continental Defense, by Robert C. Sprague [February 26, 1954] Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1953-1954) (1)-(8) 3 Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1953-1954) (9)-(12) Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1955) (1)-(9) Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C.