Chapter 2 a Slow Start for Kentucky Children Richard E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Reform and Reaction: Education Policy in Kentucky

Reform and Reaction Education Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins Copyright © 2017 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com Cover Photos “Colored School” at Anthoston, Henderson County, Kentucky, 1916. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/ncl2004004792/PP/ Beechwood School, Kenton County Kentucky, 1896. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry. com/~kykenton/beechwood.school.html Washington Junior High School at Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky, 1950s. http://www. topix.com/album/detail/paducah-ky/V627EME3GKF94BGN Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 Reform and Reaction: Fragmentation and Tarnished 1 Idylls 2 Reform Thwarted: The Trap of Tradition 13 3 Advent for Reform: Moving Toward a Minimum 30 Foundation 4 Reluctant Reform: A.B. ‘Happy” Chandler, 1955-1959 46 5 Dollars for Reform: Bert T. Combs, 1959-1963 55 6 Reform and Reluctant Liberalism: Edward T. Breathitt, 72 1963-1967 7 Reform and Nunn’s Nickle: Louie B. Nunn, 1967-1971 101 8 Child-focused Reform: Wendell H. Ford, 1971-1974 120 9 Reform and Falling Flat: Julian Carroll, 1974-1979 141 10 Silent Reformer: John Y. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Alain Locke Faith and Philosophy

STUDIES IN THE BÁBÍ AND Bahá’í Religions Volume Eighteen Alain Locke Faith and Philosophy Studies in the Bábí and Bahá’í Religions (formerly Studies in Bábí and Bahá’í History) ANTHONY A. LEE, General Editor Studies in Bábí and Bahá’í History, Volume One, edited by Moojan Momen (1982). From Iran East and West, Volume Two, edited by Juan R. Cole and Moojan Momen (1984). In Iran, Volume Three, edited by Peter Smith (1986). Music, Devotions and Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, Volume Four, by R. Jackson Armstrong-Ingram (1987). Studies in Honor of the Late H. M. Balyuzi, Volume Five, edited by Moojan Momen (1989). Community Histories, Volume Six, edited by Richard Hollinger (1992). Symbol and Secret: Qur’an Commentary in Bahá’u’lláh’s Kitáb-i Íqán, Volume Seven, by Christopher Buck (1995). Revisioning the Sacred: New Perspectives on a Bahá’í Theology, Volume Eight, edited by Jack McLean (1997). Modernity and the Millennium: The Genesis of the Baha’i Faith in the Nineteenth-Century Middle East, distributed as Volume Nine, by Juan R. I. Cole, Columbia University Press (1999). Paradise and Paradigm: Key Symbols in Persian Christianity and the Bahá’í Faith, distributed as Volume Ten, by Christopher Buck, State University of New York Press (1999). Religion in Iran: From Zoroaster to Bahau’llah, distributed as Volume Eleven, by Alessandro Bausani, Bibliotheca Persica Press (2000). Evolution and Bahá’í Belief: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Response to Nineteenth-Century Darwinism, Volume Twelve, edited by Keven Brown (2001). Reason and Revelation, Volume Thirteen, edited by Seena Fazel and John Danesh (2002). -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota. -

Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints

De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers 415 7th Street S. E., Washington, DC 20003 [email protected] (202) 578-4803 List 30, New Series Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints 19th C. American Paper ⸙ African Americana, Banking, Masons, Medical Americana, Steam Navigation, Temperance & U. S. Election History, De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers MANUSCRIPT LETTER WRITTEN FOR PUBLICATION ATTACKING J. Q. ADAMS AND PRAISING HENRY CLAY 1. (Adams, John Quincy) Open Letter Sent to the Philadelphia Newspaper, The American Sentinel, addressed “To John Q. Adams, President of the United States, & signed Lysimachus”. ca. 1828. $ 750.00 Two folio sheets of manuscript. 325 x 220 mm., [12 ¾ x 8 inches]. 4 pp., approximately 1500 words of text, written in ink in a mostly legible hand. Letter previously folded with minor tears to edges. Autograph Letter Signed with a pseudonym “Lysimachus”, known in history as a revered bodyguard of Alexander the Great. At the very top of the first leaf the words “For the A S” are written and believed to mean American Sentinel. Written by a partisan defender of Henry Clay, the author castigates John Quincy Adams for using his power to hire only those “whom you are indebted for your election. those that support you are the old hangers on.” I have been amongst the slaves, the very serfs from Europe. I have witnessed their drunken _____? and mock election but have never seen a man more perfectly worshipped and more obediently served than yourself. The slaves that now uphold you be assured will not continue their support when it most will be needed. Their obligation will terminate with your downfall. -

Statement, June 1978

MOREHEAD STATE!NjJ~fl)Jl: People, Programs and Progress at Morehead State Univers ity Vol. 1, N o. 5 M orehead, Ky. 4035 1 June, 1978 To find,get and hold a job It's official name is the "employability skil ls project" Essential ly, the program teaches individuals to use but to the growing number of persons benefiting from various sources of job information, to plan personal and Morehead State University's newest regional service vocational goals, to effectively present themselves to effort, it is the "job course." prospective employers and to develop good work habits. In simple terms, its purpose is to help Kentuckians Since its beginning last fall under a grant from the choose, f ind, get and keep a job of their choice. It is the U.S. Office of Education, the program has enrolled 170 first program of MSU's new Appalachian Development students at 10 locations, including Morehead, Mt. Center and, if the growing demand for the instruction is Sterling, Ashland, Lexington, Louisville and Beattyville. an indication of success, the "job course" is on target. The Lexington and Louisville classes were required by ''Our goal is to help our people be more competitive the funding agency for comparative purposes. in today's job market," said Gary Wilson, project The project utilizes the Adkins Life Skills Program, a coordinator and one of three instructors. "Our clientele series of 10 units of instruction developed by Dr. Win range from high school and college students to senior Adkins of Columbia University. Refined over a citizens but all have determined that they need to seven-year period, the program uses a multi-media improve t heir job-related skills." approach and other teaching techniques. -

(Kentucky) Democratic Party : Political Times of "Miss Lennie" Mclaughlin

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-1981 The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin. Carolyn Luckett Denning 1943- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Denning, Carolyn Luckett 1943-, "The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin." (1981). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 333. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/333 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: " POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 1981 © 1981 CAROLYN LUCKETT DENNING All Rights Reserved THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Approved on <DatM :z 7 I 8 I By the Following Reading Committee Carol Dowell, Thesis Director Joel /Go]tJstein Mary K.:; Tachau Dean Of (j{airman ' ii ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to examine the role of the Democratic Party organization in Louisville, Kentucky and its influence in primary elections during the period 1933 to 1963. -

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY in 2019, We Provided Selected Museum Student Workers a List of Twenty Women

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY In 2019, we provided selected Museum student workers a list of twenty women and asked them to do initial research, and to identify items in the Rather-Westerman Collection related to women in Kentucky political life. Page Mary Barr Clay 2 Laura Clay 4 Lida (Calvert) Obenchain 7 Mary Elliott Flanery 9 Madeline McDowell Breckinridge 11 Pearl Carter Pace 13 Thelma Stovall 15 Amelia Moore Tucker 18 Georgia Davis Powers 20 Frances Jones Mills 22 Martha Layne Collins 24 Patsy Sloan 27 Crit Luallen 30 Anne Northup 33 Sandy Jones 36 Elaine Walker 38 Jenean Hampton 40 Alison Lundergan Grimes 42 Allison Ball 45 1 Political Bandwagon: Biographies of Kentucky Women Mary Barr Clay b. October 13, 1839 d. October 12, 1924 Birthplace: Lexington, Kentucky (Fayette County) Positions held/party affiliation • Vice President of the American Woman Suffrage Association • Vice President of the National Woman Suffrage Association • President of the American Woman Suffrage Association; 1883-? Photo Source: Biography https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Barr_Clay Mary Barr Clay was born on October 13th, 1839 to Kentucky abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay and Mary Jane Warfield Clay in Lexington, Kentucky. Mary Barr Clay married John Francis “Frank” Herrick of Cleveland, Ohio in 1839. They lived in Cleveland and had three sons. In 1872, Mary Barr Clay divorced Herrick, moved back to Kentucky, and took back her name – changing the names of her two youngest children to Clay as well. In 1878, Clay’s mother and father also divorced, after a tenuous marriage that included affairs and an illegitimate son on her father’s part. -

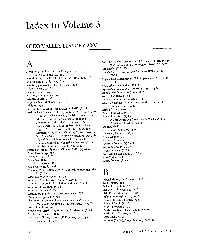

Index to Volume 3

Index to Volume 3 OHIO VALLEY HISTORY 2003 Apelt, Brian, The Corporation: A Centennial Biography of A United States Steel Corporation, 1901 -2001, (3) 79 81 Appaiachia, 11) 31-43 Abington School District u. Schempp, (3)34 Appalachia: A History, John Alexander Williams, (3) A & I Wolf and Co, (1)2 77-78 abolitionism, (1)6-12, 14; Old Line abolitionism, (1) 10 Appalachian Committee for Full Employment (ACFE), (1) abolitionists, (1)3-4, (2)3, 10, 12 37,38 activism, grass-roots, (1)31-43; social, (1)31 Appalachian Mountains, (4)4, 13 Adams, James, (2) 11 App&&an Regional Commission (ARC), (1)34 Adams, John, (4)26 Appalachian Volunteers (Avs), (1) 39 Adams, John Quincy, (3) 63 Appleby, Monica, (4) 62 Adams, Luther, (3) 37 apprentices, acts concernifig, (1) 11 Adjutant General of Georgia, (4) 48 Area Development Administration of the Department of adultery, (4) 6-7 Commerce, (1)39,41 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2) 13 Armed Forces, (3) 44 African Americarls, (1) 3-4, 7-8, 26, (2) 3-15, 31-43, 50, (7) Army of the Ohio, (4)47 37-50, (4) 38-39; as slaves, (2) 3-15; as fugitive slave, Army of the West, (4) 13 3-8; and cxodus from Cincirinati, (2) 8; and Art as Image: Prints and Promotion in Cincinnati, Ohio, Underground Railroad, (2) 12; women, (2)13; Alice Cornell, ed., (3)74-76 Cincinnatians, (2) 13; as solcliers, (2)35,37-39; and artiller~: (4) 40 religion, (2)31-32; conversions, (2)32, 35; and artisans, German-born, (1)19 Christianity, (2)38; and chuickes, \I\$0; as Ba@h, Ashendel, Anita, (1)1-2, 17 (2)42; migrants, (3) 37-50; conception of South, (3) Athenaeum, (3) 20 3 7; and their neighborhoods, (3)39; racial Atlanta, Georgia, (3)43 discrimination of, (3) 40; and employment, (3) 45; Attorney General, (4) 29-30 and civil fights movement, (1)42, (3)47-48 auctions, land, (4) 25-27 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2)40,42 Austin, Stephen, (3)53 Afro-Christianity, (2) 3 1 hyddort, Dr. -

Empowering and Inspiring Kentucky Women to Public Service O PENING DOORS of OPPORTUNITY

Empowering and Inspiring Kentucky Women to Public Service O PENING DOORS OF OPPORTUNITY 1 O PENING DOORS OF OPPORTUNITY Table of Contents Spotlight on Crit Luallen, Kentucky State Auditor 3-4 State Representatives 29 Court of Appeals 29 Government Service 5-6 Circuit Court 29-30 Political Involvement Statistics 5 District Court 30-31 Voting Statistics 6 Circuit Clerks 31-33 Commonwealth Attorneys 33 Spotlight on Anne Northup, County Attorneys 33 United States Representative 7-8 County Clerks 33-35 Community Service 9-11 County Commissioners and Magistrates 35-36 Guidelines to Getting Involved 9 County Coroners 36 Overview of Leadership Kentucky 10 County Jailers 36 Starting a Business 11 County Judge Executives 36 County PVAs 36-37 Spotlight on Martha Layne Collins, County Sheriffs 37 Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky 12-13 County Surveyors 37 Kentucky Women in the Armed Forces 14-19 School Board Members 37-47 Mayors 47-49 Spotlight on Julie Denton, Councilmembers and Commissioners 49-60 Kentucky State Senator 20-21 Organizations 22-28 Nonelected Positions Statewide Cabinet Secretaries 60 Directory of Female Officials 29-60 Gubernatorial Appointees to Boards and Commissions since 12/03 60-68 Elected Positions College Presidents 68 Congresswoman 29 Leadership Kentucky 68-75 State Constitutional Officers 29 State Senators 29 Acknowledgments We want to recognize the contributions of the many Many thanks also go to former Secretary of State Bob who made this project possible. First, we would be Babbage and his staff for providing the initial iteration remiss if we did not mention the outstanding coopera- for this report.