Alain Locke Faith and Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

A Historical Coalition Between the Hands of the Cause and the Covenant-Breakers

A Historical Coalition between the Hands of the Cause and the Covenant-Breakers Dear Friends, Baha’u’llah made it incumbent upon every believing Baha’i to prepare a will and testament (the most Holy Book, para 255) during his life time. And he followed his own command when he wrote a will and appointed an heir, so that his family and followers would not face any such difficulties after him. In the same way, Abdul-Baha considered it necessary to write a will during one’s life, having also written his own valuable Will and Testament, which includes his important edicts and recommendations. According to the most Holy Book, if a Baha’i dies and does not leave a will, all of his or her belongings and properties should be divided among the following seven groups: spouse, children, father, mother, brother(s), sister(s) and teacher. And according to the Kitab-i Aqdas, if any member of the above categories were deceased, his or her share will be inherited by the UHJ. Finally, according to that same Holy Book, all non-Baha’is, non-believers, Covenant-breakers, and those excommunicated from the Faith, are deprived from a Baha’i's estate. 1 Now, I would like to draw your attention to a very important event in the history of the Baha’i community. As you are well aware, the Beloved Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, passed away in London in the summer of 1957. He journeyed to London in order to purchase necessary material to complete the archives buildings. There, he died having suffered from a previously-undiagnosed disease. -

THE UNIVERSAL HOUSE of JUSTICE 18 February 2008

THE UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE 18 February 2008 Transmitted by email The Friends in Iran Dear Bahá’í Friends, We have received a letter from a believer in Iran with questions about the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice. We appreciate that firmness in the Covenant is among the distinctive characteristics of the believers in that land, who are informed of the principles and essential facts pertaining to the succession of authority in the Cause. Nevertheless, none among them should hesitate to seek clarification of matters about which they have questions, for the enemies of the Faith are tireless in their attempts to sow seeds of confusion and doubt. Moreover, it is beneficial, in view of the beloved Master’s exhortations to us all to be ever- vigilant concerning matters of protection, for the friends to review the relevant essentials from time to time. We have therefore decided to provide you with the following comments. In this connection, you are also encouraged to reacquaint yourselves with the document “Mason Remey and Those Who Followed Him”, a statement prepared at our instruction by an ad hoc committee. A translation of the statement is enclosed. Questions concerning the Guardianship and the Universal House of Justice can be resolved through careful study of the writings of Bahá’ulBahá'u'lláh, láh, ‘Abdul‘Abdu’l-Bahá -Bahá and Shoghi Effendi and the elucidations of the House of Justice, which, ‘Abdul‘Abdu’l-Bahá -Bahá states, will “deliberate upon all problems which have caused difference, questions that are obscure and matters that are not expressly recorded in the Book. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

The Hilltop 5-8-1954

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 1950-60 The iH lltop Digital Archive 5-8-1954 The iH lltop 5-8-1954 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_195060 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 5-8-1954" (1954). The Hilltop: 1950-60. 28. http://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_195060/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 1950-60 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • .. • • TBUIGOOD 'MARSBALfi· TO BE HONORED AT· COMMENCEMENT -- • Page 5 • - - I .. - - . ' ' . , __ 1 • VOTE! I• VOTE! • • • . .. • • ..J VOL 36, NO. 7 HOW ARD UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C. ~IAY 8, 1954 ' • ' ' - , • After 30 Y ear1: • .. • Student Leaders Endorse Increase In Ancient Student Activity Fee ~ . The long-awaited rise in student al:tivity fees could be just a.round the corner, if recent actions and discussions are any indica tions. Several groups are now studying the plan to have the pre.~o~ fee of $1.60 in~reased to $5.00. For years, now, student activities have been facing s lo~w strangulation, for want of adequate operating funds. (The $1.50 per semester fee was set almost ao years ago.) Lucien Cox, president o! the 24 Years Service: Student Council, expressed the sentiment of the council recently , when he told HILLTOP editors Dean Price Among " With each student paying just $1.50 per semester for student Four to Retire activit~es , there aren't going to Dr. -

The Ministry of Shoghi Effendi

The Ministry of Shoghi Effendi Will and Testament of `Abdu’l-Baha • He delineated the • `Abdu’l-Bahá revealed a authority of “twin Will and Testament in successor” institutions three parts, 1902 to 1910, • He further defined where He designated responsibilities of the Shoghi Effendi as His Hands of the Cause successor and elaborated on the election of the • `Abdu’l-Bahá almost Universal House of Justice never mentioned to anyone that Shoghi • We’ll look at some Effendi would succeed passages later Him; it was a well kept secret Shoghi Effendi Rabbani • Born March 1, 1897; eldest of 13 grandchildren of `Abdu’l-Bahá • Mother was `Abdu’l-Bahá’s oldest daughter (of 4) • `Abdu’l-Bahá insisted everyone address him with the term Effendi (Turkish for sir) • Education in home school in Akka (in the House of Abbud) first by a Persian man, then by an Italian governess Education • Then went to the College • He was devastated and des Freres in Haifa, a lost weight Jesuit private school • He very strongly disliked • Then went to a Jesuit the French high school, boarding school in Beirut though he learned fluent • Invited to go to America French there with `Abdu’l-Bahá, but he • Started his senior year at was turned back in Syrian Protestant College Naples on the claim his Preparatory School, Oct. eyes were diseased with 1912, when 15 years old trachoma • Graduated in early summer 1913 (age 16) Higher Education • Summer 1913: In Egypt • Bachelor of Arts degree with `Abdu’l-Bahá when he was 20 (the • Syrian Protestant graduating class had college, 1913-17 10!) • The college did relief • Graduate student at work and provided free SPC, fall 1917-summer medical care to Turkish 1918 soldiers, so it was • Sept. -

Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints

De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers 415 7th Street S. E., Washington, DC 20003 [email protected] (202) 578-4803 List 30, New Series Manuscripts, Broadsides & Prints 19th C. American Paper ⸙ African Americana, Banking, Masons, Medical Americana, Steam Navigation, Temperance & U. S. Election History, De SIMONE COMPANY, Booksellers MANUSCRIPT LETTER WRITTEN FOR PUBLICATION ATTACKING J. Q. ADAMS AND PRAISING HENRY CLAY 1. (Adams, John Quincy) Open Letter Sent to the Philadelphia Newspaper, The American Sentinel, addressed “To John Q. Adams, President of the United States, & signed Lysimachus”. ca. 1828. $ 750.00 Two folio sheets of manuscript. 325 x 220 mm., [12 ¾ x 8 inches]. 4 pp., approximately 1500 words of text, written in ink in a mostly legible hand. Letter previously folded with minor tears to edges. Autograph Letter Signed with a pseudonym “Lysimachus”, known in history as a revered bodyguard of Alexander the Great. At the very top of the first leaf the words “For the A S” are written and believed to mean American Sentinel. Written by a partisan defender of Henry Clay, the author castigates John Quincy Adams for using his power to hire only those “whom you are indebted for your election. those that support you are the old hangers on.” I have been amongst the slaves, the very serfs from Europe. I have witnessed their drunken _____? and mock election but have never seen a man more perfectly worshipped and more obediently served than yourself. The slaves that now uphold you be assured will not continue their support when it most will be needed. Their obligation will terminate with your downfall. -

Campus News February 21, 1997 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Campus News University Publications 2-21-1997 Campus News February 21, 1997 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/campus_news Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Campus News February 21, 1997" (1997). Campus News. 1279. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/campus_news/1279 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campus News by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAMP US NEWS LA SALLE UNIVERSITY'S WEEKLY INFORMATION CIRCULAR February 21,1997 La Salle U niversity Office of the President Philadelphia. PA 19141 • (215)951-1010 • FAX (215)951-1783 TO: The La Salle Community FROM: Brother Joseph Burke DATE: February 19, 1997 RE: The Provost Citing personal reasons, our Provost, Dr. Joseph Kane, has informed me that he intends to return to faculty status, resigning from the position of Provost sometime prior to the beginning of the 1997-1998 academic year. Reluctantly, I have accepted his resignation. Dr. Kane has been a part of La Salle University for 36 years. After serving as Dean of the School of Business Administration for 10 years, Dr. Kane served as Interim Provost and then Provost since October, 1994. His tenure as Provost has been marked by collaborative leadership, a thoughtful vision of La Salle’s future, and a commitment to the well-being of our faculty and students. He has provided leadership and initiative in so many ways: founding the MBA program, orchestrating our AACSB accreditation, piloting us through Middle States accreditation, integrating Academic Affairs and Student Affairs, and initiating curriculum reform, to name but a few. -

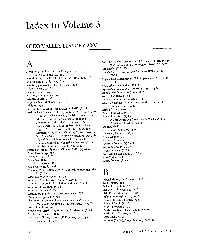

Index to Volume 3

Index to Volume 3 OHIO VALLEY HISTORY 2003 Apelt, Brian, The Corporation: A Centennial Biography of A United States Steel Corporation, 1901 -2001, (3) 79 81 Appaiachia, 11) 31-43 Abington School District u. Schempp, (3)34 Appalachia: A History, John Alexander Williams, (3) A & I Wolf and Co, (1)2 77-78 abolitionism, (1)6-12, 14; Old Line abolitionism, (1) 10 Appalachian Committee for Full Employment (ACFE), (1) abolitionists, (1)3-4, (2)3, 10, 12 37,38 activism, grass-roots, (1)31-43; social, (1)31 Appalachian Mountains, (4)4, 13 Adams, James, (2) 11 App&&an Regional Commission (ARC), (1)34 Adams, John, (4)26 Appalachian Volunteers (Avs), (1) 39 Adams, John Quincy, (3) 63 Appleby, Monica, (4) 62 Adams, Luther, (3) 37 apprentices, acts concernifig, (1) 11 Adjutant General of Georgia, (4) 48 Area Development Administration of the Department of adultery, (4) 6-7 Commerce, (1)39,41 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2) 13 Armed Forces, (3) 44 African Americarls, (1) 3-4, 7-8, 26, (2) 3-15, 31-43, 50, (7) Army of the Ohio, (4)47 37-50, (4) 38-39; as slaves, (2) 3-15; as fugitive slave, Army of the West, (4) 13 3-8; and cxodus from Cincirinati, (2) 8; and Art as Image: Prints and Promotion in Cincinnati, Ohio, Underground Railroad, (2) 12; women, (2)13; Alice Cornell, ed., (3)74-76 Cincinnatians, (2) 13; as solcliers, (2)35,37-39; and artiller~: (4) 40 religion, (2)31-32; conversions, (2)32, 35; and artisans, German-born, (1)19 Christianity, (2)38; and chuickes, \I\$0; as Ba@h, Ashendel, Anita, (1)1-2, 17 (2)42; migrants, (3) 37-50; conception of South, (3) Athenaeum, (3) 20 3 7; and their neighborhoods, (3)39; racial Atlanta, Georgia, (3)43 discrimination of, (3) 40; and employment, (3) 45; Attorney General, (4) 29-30 and civil fights movement, (1)42, (3)47-48 auctions, land, (4) 25-27 African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), (2)40,42 Austin, Stephen, (3)53 Afro-Christianity, (2) 3 1 hyddort, Dr. -

Religious and Social Life of Religious Minorities

RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL LIFE OF RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A CASE STUDY OF BAHÁ’Í AND PARSI COMMUNITIES OF PAKISTAN Abdul Fareed 101-FU/PhD/F08 DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE RELIGION FACULTY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES, INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL LIFE OF RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A CASE STUDY OF BAHÁ’Í AND PARSI COMMUNITIES OF PAKISTAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in Comparative Religion By Abdul Fareed Registration no. 101-FU/PhD/F08 Under the Supervision of Dr. Muhammad Imtiaz Zafar DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE RELIGION FACULTY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES, INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD ١ذو القعدة ١٤١٦ من الهجرة /Submitted on: August17, 2015 C.E Statement of Undertaking I Abdul Fareed Reg. No. 101/FU/PHD/F-08 and student of Ph.D. Comparative Religion, Faculty of Islamic Studies, International Islamic University Islamabad do hereby solemnly declare that the thesis entitled ‘ Religious and Social Life of the Religious Minorities: A case Study of Bahá’í and Parsi Communities of Pakistan’ submitted by me in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. is my original work, except where otherwise acknowledge in the text, and has not been submitted or published earlier and so not in future, be submitted by me for any degree this University or institution. Abdul Fareed APPROVAL It is certified that Mr. Abdul Fareed s/o Abdul Raheem Reg.No.101-FU/PhD/F08 has successfully defended his thesis titled: Religious and Social Life of the Religious Minorities: A case Study of Bahá’í and Parsi Communities of Pakistan in viva-voce examination held in the Department of Comparative Religion, Faculty of Islamic Studies( Usuluddin) , International Islamic University, Islamabad. -

The Negro in France

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Black Studies Race, Ethnicity, and Post-Colonial Studies 1961 The Negro in France Shelby T. McCloy University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation McCloy, Shelby T., "The Negro in France" (1961). Black Studies. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_black_studies/2 THE NEGRO IN FRANCE This page intentionally left blank SHELBY T. McCLOY THE NEGRO IN FRANCE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Copyright© 1961 by the University of Kentucky Press Printed in the United States of America by the Division of Printing, University of Kentucky Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 61-6554 FOREWORD THE PURPOSE of this study is to present a history of the Negro who has come to France, the reasons for his coming, the record of his stay, and the reactions of the French to his presence. It is not a study of the Negro in the French colonies or of colonial conditions, for that is a different story. Occasion ally, however, reference to colonial happenings is brought in as necessary to set forth the background. The author has tried assiduously to restrict his attention to those of whose Negroid blood he could be certain, but whenever the distinction has been significant, he has considered as mulattoes all those having any mixture of Negro and white blood. -

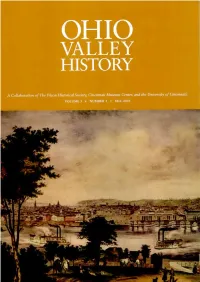

Fall-2003.Pdf

OHIO ALLEY EDITORIAL BOARD HIS'/ORY · STAFF Compton Allyn Christine 1..Heyrman joseph R Reidy Cincimiati Museum Center Editors University of Delaware Howard University History Advisory Board Wayne K. Durrill J. Blaine Hudson Steven J. Ross Christopher Phillips Stephen Aron University of 1 ouisuille University of ilitbern Department of History University of Califoynia Califwma R. Douglas Hurt University of Cincinnati al Los Angeles Iowa State University Harry N. Scheiber Joan E. Cashin University of Calif,) Managing Editors James C. Klotter rnia Obio State Umversity Berkeley Jennifer Reiss Georgetown College at The Filson Historical Society Andrew R. L. Cayton Steven M. S[o,ve Bruce I.evine Mioinj University indiana Uliwer:ity Ruby Rogers University of California Cincinnati Museum Center R. David Edmunds at Santa Ci·Hz Roger D. Tate University of Texas at Dallas Somerset Commitility Editon'at Assistant Zane L. Miller College Kelly Wright Ellen T. Eslinger Ultiversit,of Cincinnati DePatil Uiliversity Joe W.Trotter,Jr. Department of History Elizabeth A. Perkins University of Cilicilinati Caniegie Mellon University Craig T Friend Centre College University of Central Florida Altina Waller A. Ramage James University of Connecticut Northern Kentucky U,iiversity C]NCINNATI MUSEUM CENTER THE F[i.SON HIS7'ORICAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES SOC[ETY BOAR!)01: DIRECTORS Cbair Helen Black Robert E Kistinger President H. C. Buck Niehoff David Bohi Laura Long Dr. R. Ted Steinbock Ronald D. Brown Steven R. Love Past Chair Vice-President Otto M. Budig,Jr. Craig Maier Valerie L. Newell Emily S. Bingham Brian Carley Shenan R Murphy Chairs Vice Richard 0. Coleman Robert Olson Secretary-Treasurer Ken Lowe Bob Coughlin Scott Robertson Henry Ormsby Greg Kenny Diane L.