The Trinity Review, May 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Concerning the Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 Affaire Relative a L'incident Aérien Du 27 Juillet 195 5

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS CASE CONCERNING THE AERIAL INCIDENT OF 27 JULY 1955 (UNITED KINGDOM v. BULGARIA) OBDER OF 3 AUGUST 1959 COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRETS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES AFFAIRE RELATIVE A L'INCIDENT AÉRIEN DU 27 JUILLET 195 5 (ROYAUME-UNI C. BULGARIE) ORDONNANCE DU 3 AOÛT 1959 This Order should be cited as follows: "Case concerning the Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 (United Kingdom v. Bulgaria) , Order of 3 August 1959: I.C.J. Reports 19-59, p. 264." La présente ordonnance doit être citée comme suit: Afa.ire relative à l'incident aérien du 27 juillet 1955 (Royaume-Uni c. Bulgarie), Ordonnance dzt 3 août 1959: C. I. J. Recueil 1959, p. 264. » -- - -- Sales number NO de vente : 2'11 INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE 1959 YEAR 1959 3 Augus: General List: 3 August 1959 CASE CONCERNING THE AERIAL INCIDENT OF 27 JuLy 1911 (UNITED KINGDOM v. BULGARIA) ORDER The President of the International Court of Justice, having regard to Article 48 of the Statute of the Court and to Article 69 of the Rules of Court; Having regard to the Application, dated 19 November 1957 and filed in the Registry of the Court on 22 November 1957, by which the Govemment of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Nor- them Ireland instituted proceedings before the Court against the Govemment of the People's Republic of Bulgaria with regard to the losses sustained by citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies by reason of the destruction, on 27 July 1955, by the Bulgarian anti- aircraft defence forces, of an aircraft belonging to El Al Israel Airlines Ltd. -

Department of Finance and Administration Correspondence 1959-1962

DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATION CORRESPONDENCE 1959-1962 RECORD GROUP 272 by Ted Guillaum Archival Technical Services Tennessee State Library & Archives Date Completed: September 28,1999 MICROFILM ONLY INTRODUCTION Record Group 272, Department of Finance and Administration, Correspondence, spans the years 1959 through 1962 with the majority of the records focusing on the years 1959 through 1961. The correspondence of two commissioners of the Department of Finance and Administration is represented in this collection. The commissioners were Edward J. Boling and Harlan Mathews. Edward J. Boling served from February, 1959 through August, 1961. Harlan Mathews was appointed commissioner in September of 1961. These records reflect the various activities connected with the administration of financial and budgetary matters of the Executive branch. Original order was maintained during processing. These records were transferred to the archives in good condition in 1983. The original size of the collection was about eight cubic feet but was reduced to seven cubic feet by the elimination of duplicate copies and extraneous material. The collection was microfilmed and all documents were destroyed. There are no restrictions to access. SCOPE AND CONTENT Record Group 272, Department of Finance and Administration, Correspondence, spans the period 1959 through 1962, although the bulk of the collection is concentrated within the period 1959 through 1961. The collection consists of seven cubic feet of material that has been microfilmed and the originals were destroyed. The original order of this collection was maintained during processing. The arrangement of this collection is chronological for the period of 1959 through 1960. The remainder of the collection is chronological, then alphabetical by topics. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

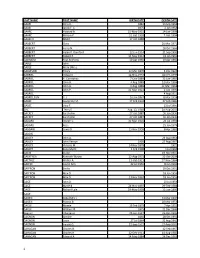

LAST NAME FIRST NAME BIRTH DATE DEATH DATE GAAEI Dora K

LAST NAME FIRST NAME BIRTH DATE DEATH DATE GAAEI Dora K. 1882 13 Sep 1968 GAAEI Jacob F. C. 1875 2 Jan 1958 GAARE Howard A. 15-May-1915 14-Jan-1998 GAARE Miriam K. 31-Oct-1918 7-Oct-1994 GAASCH Albert 17 Oct 1888 GABBERT Clara 20 Mar 1971 GABBERT Harry N. 18 Oct 1966 GABBERT Helen P. Rumford 12 Jun 1914 21 Sep 1992 GABBERT Robert E. 11 May 1912 24 Jan 1991 GABHARD Paul Anthony 10 Apr 1960 10 Apr 1960 GABLE John GABLE Mary (Mrs.) GABLESON Henry 12 Mar 1870 6 Dec 1924 GABRIEL Edward 12-Nov-1937 April 9, 1995 GABRIEL H. Constance 7-Dec-1889 31-Jan-1985 GABRIEL John A. 4 Aug 1889 12 Mar 1968 GABRIEL John A. 4-Aug-1889 12-Mar-1968 GABRIEL John P. 31-Mar-1923 2-Jun-1993 GABRIEL 4 Aug 1911 GABRIELSON H. J. 10 Jan 1867 8 Mar 1918 GABSE Josephine M. 17 Feb 1904 27 Feb 1980 GABSE Otto F. 23 Jul 1960 GAC Terry S. Aug. 12, 1948 24-Aug-2003 GACKEY Sarah Ann 27 Oct 1887 30 Jan 1930 GACKEY Sarah Ann 27 Oct 1887 30 Jan 1930 GADARD Joseph C. 30-Mar-1901 26-Jul-1994 GADARD Rose 25 Jan 1979 GADBAW Lewis B. 15 Nov 1909 8 Apr 1982 GADDIS GADLEY John A. 24 Aug 1964 GADLEY John Vernon 1950 27 Aug 1967 GADLEY Victoria M. 24 Nov 1878 1921 GADLEY Zona Myrle 2 Feb 1908 1 Jul 1994 GAENI Crape 19 Nov 1907 GAERTNER Kenneth Wayne 22-Aug-1931 31-Oct-2009 GAETHLE Walter A. -

NSC Series, Subject Subseries

WHITE HOUSE OFFICE, OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ASSISTANT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS: Records, 1952-61 NSC Series, Subject Subseries CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Arms Control, U.S. Policy on [1960] Atomic Energy-The President [May 1953-March 1956] (1)(2) [material re the function of the special NSC committee to advise the President on use of atomic weapons] Atomic Weapons, Presidential Approval and Instructions for use of [1959-1960] (1)- (5) Atomic Weapons, Correspondence and Background for Presidential Approval and Instructions for use of [1953-1960] (1)-(6) Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (1) [1953-1954] [nuclear powered aircraft; Nevada atomic weapons tests; Department of Defense participation in the weapons program] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (2) [1952-54] [custody of atomic weapons] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (3) [1953-54] [transfer and deployment of nuclear weapons; operation TEAPOT] Atomic Energy-Miscellaneous (4) [1953-54] [safety tests; weapons program; development of fuel elements for nuclear reactors] Atomic Weapons and Classified Intelligence-Misc. (1) [1955-1957] [test moratorium on nuclear weapons; development of a high yield weapon] Atomic weapons and Classified Intelligence-Misc. (2) [1954-1960] [disclosures of classified intelligence; downgrading, declassification and publication of NSC papers] 2 Base Rights [November 1957-November 1960] (1)-(4) [U.S. overseas military bases] Study of Continental Defense, by Robert C. Sprague [February 26, 1954] Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1953-1954) (1)-(8) 3 Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1953-1954) (9)-(12) Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. Sprague (1955) (1)-(9) Continental Defense, Study of-by Robert C. -

Berlin and the Cold War

BERLIN AND THE COLD WAR BEACH, EDWARD L. AND EVAN P. AURAND: Records, 1953-61 Series I: Presidential Trips Box 2 President Eisenhower’s Trip to United Kingdom, Aug 27-Sept 7, 1959 [Topics of discussion between Eisenhower and DeGaulle; meeting between President Eisenhower and Chancellor Adenauer] BENEDICT, STEPHEN: Papers, 1952-1960 Box 2 9-22-52 Evansville, Indiana [Berlin airlift] Box 10 Teletype Messages, September-October 1952 [Germany and Berlin] BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-68 Box 2 Correspondence (1) (2) [John Toland re The Last 100 Days] BURNS, ARTHUR F. Papers, 1928-1969 Box 90 Germany, 1965--(State Department Correspondence) COMBINED CHIEFS OF STAFF: Conference Proceedings, 1941-1945 Box 3 Argonaut Conference, January-February 1945, Papers and Minutes of meetings Box 3 Terminal Conference, July 1945: Papers and Minutes of Meetings DULLES, ELEANOR L.: Papers, 1880-1984 Box 12 Germany and Berlin, 1950-53 Box 12 Germany and Berlin, 1954-56 Box 13 Germany and Berlin, 1957-59 Box 13 Briefing Book on Germany (1)–(4) – 1946-57 Box 13 Congress Hall, Berlin, 1957 (1) (2) Box 13 Congress Hall Scrapbook, Sept. 1957 (1) (2) Box 13 Congress Hall Booklets, 1957-58 Box 13 Congress Hall Clippings, 1955-58 Box 13 Berlin Medical Teaching Center, 1959 Box 14 Berlin Medical Center Dedication, 1968 Box 14 Reports on Berlin, 1970-73 Box 14 Notes re Berlin, 1972 Box 19 ELD Correspondence, 1971 (1) (2) Berlin Box 19 ELD Correspondence, 1972 (1) (2) Berlin Box 20 ELD Correspondence, 1973 (1) (2) –Berlin Box 20 ELD Correspondence, 1974 (1) (2) – Willy -

International Series

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS WHITE HOUSE OFFICE, OFFICE OF THE STAFF SECRETARY: Records of Paul T. Carroll, Andrew J. Goodpaster, L. Arthur Minnich and Christopher H. Russell, 1952-61 International Series CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Afghanistan (1) [1958-1959] Afghanistan (2) [1960] Africa (General) (1) [December 1958 - January 1961] [articles re the “African Revolution,” tripartite talks on Africa] Africa (General) (2) [UN Security Council discussion of South Africa] Africa (General) (3) [visits to Washington, D.C. of African leaders, U.S. financial aid to African countries] Africa (Republics) [1960] (1) [Central African Republic, Chad, Dahomey, Gabon] Africa (Republics) (2) [Ivory Coast, Malagasy Republic] Africa (Republics) (3) [Mali] Africa (Republics) (4) [Mauritania, Niger] Africa (Republics) (5) [Nigeria] Africa (Republics) (6) [Senegal, Somali Republic] Africa (Republics) (7) [Togo, Upper Volta] Algeria [August 1959 - December 1960] Argentina (1) [June 1958 - January 1960] Argentina (2) [February-May 1960] Argentina (3) [June-September 1960] Australia [September 1958 - December 1960] Austria [July 1958 - September 1960] Belgium [March 1959 - December 1960] 2 Bolivia [March 1959 - August 1960] Brazil (1) [May 1958 - January 1960] Brazil (2) [February 1960] Brazil (3) [March-December 1960] Bulgaria [March 1959 - September 1960] Burma [March 1959 - May 1960] Cambodia (1) [February-June 1959] Cambodia (2) [June 1959 - June 1960] Cambodia (3) [July 1960 - January 1961] Cameroun [June 1959 - October 1960] Canada -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 6 11 11 2019 - 2020 0 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June -

GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY: FIFTH SUPPLEMENT August 195Ô

GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY: FIFTH SUPPLEMENT August 195Ô - July 1959 GATT Secretariat Villa Le Bocage Palais des Nations Geneva August 1959 Switzerland M3T(59)95 MJP(59)95 Page 1 GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY; FIFTH SUPEL3,ISNT The GATT Bibliography was first published in Ilarch 1954 and covered the period from 1947 to the end of 1953. The First Supplement covered the period from January 1954 to June 1955. The Second Supplement covered the period from June 1955 to June 1956; the Third Supplement from June 1956 to August 1957; the Fourth Supplement from August 1957 to July 1958; the Fifth Supplement from August 1958 to July 1959. Among the main events referred to in the Fifth Supplement are: the thirteenth session of the CONTRACTING PriRTJSS, from 16 October to 22 November 1958; the fourteenth session from U May to 30 May 1959; the publication of Trends in International Trade on 12 October 1958; and the development of the GATT programme for the expansion of international trade. Note: The GATT Bibliography and it3 Supplements do not include the publications 0* the GATT secretariat. These are contained in the Liot of Official Material relating to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, obtainable on request from the secretariat* MGT(59)95 Page 2 May 1958 Théorie und Praxis des GATT. Vplkswirt (Prankfort a/M,): 867-868 9 May 1959, Enrique Arocena Olivera y Enrique Ferri, El GATT, su ©structura y sus proyocciones sobre la realidad economica iberoamericana. Revista de Economic a (Montevideo), December-May 1957-58. Magnifico, G.: Il mercato comune europeo e il GATT. -

May 16, 1959 Statement Made by the Chinese Ambassador to the Foreign Secretary, 16 May 1959

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified May 16, 1959 Statement made by the Chinese Ambassador to the Foreign Secretary, 16 May 1959 Citation: “Statement made by the Chinese Ambassador to the Foreign Secretary, 16 May 1959,” May 16, 1959, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed between the Governments of India and China 1954-1959: White Paper I (New Delhi: External Publicity Division, Ministry of External Affairs, 1959), 73-76. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/175950 Summary: Original Language: English Contents: Scan of Original Document Statement made by the Chinese Ambassado1· to the Foreign Secreta1·y, 16 May 1959 Since March 10. 1959 when the former Tibet Local Government and the Tibetan upper class reactionary clique unleashed armed rebellion, there have appeared deplorable abnormalities in the relations between China and India. This situation was caused by the Indian side, yet in his conversation on April 26, 1959 Mr. Dutt, Foreign Secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs of India, shifted responsibility onto the Chinese side. This is what the Chinese Government absolutely cannot .accept-. · The Tibet Region is an inalienable part of China's territory. The quelling of the rebellion in the Tibet Region by the Chinese Govern ment and following that, the conducting by it of democratic reforms which the Tibetan people have longed for, are entirely China's inter nal affairs, in which no foreign country has any right to interfere under whatever pretext or in whatever form. In Tibet, just as in other national minority areas in China, regional national autonomy shall be implemented as stipulated in the Constitution of the People's "Republic of China. -

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS, OFFICE OF: Printed Material, 1953-61

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS, OFFICE OF: Printed Material, 1953-61 Accession A75-26 Processed by: TB Date Completed: December 1991 This collection was received from the Office of Emergency Preparedness, via the National Archives, in March 1975. No restrictions were placed on the material. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 5.2 Approximate number of pages: 10,400 Approximate number of items: 6,000 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE This collection consists of printed material that was collected for reference purposes by the staff of the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM) and the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM). The material was inherited by the Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP), a successor agency to ODM and OCDM. After the OEP was abolished in 1973 the material was turned over to the National Archives and was then sent to the Eisenhower Library. The printed material consists mostly of press releases and public reports that were issued by the White House during the Eisenhower administration. These items are arranged in chronological order by date of release. Additional sets of the press releases are in the Kevin McCann records and in the records of the White House Office, Office of the Press Secretary. Copies of the reports are also in the White House Central Files. The collection also contained several books, periodicals and Congressional committee prints. These items have been transferred to the Eisenhower Library book collection. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Items Transferred -

1. A) Amendments to Articles 24 and 25 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization

1. a) Amendments to articles 24 and 25 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization Geneva, 28 May 1959 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 25 October 1960, in accordance with article 73of the Constitution, for all Members of the World Health Organization*. REGISTRATION: 25 October 1960, No. 221. STATUS: Parties* TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 377, p. 380. Note: The amendments to articles 24 and 25 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization were adopted by the Twelfth World Health Assembly by resolution WHA 12.43 of 28 May 1959. In accordance with article 73 of the Constitution, amendments come into force for all Members when adopted by a two- thirds vote of the Health Assembly and accepted by two-thirds of the Members in accordance with their respective constitutional processes. Following is the list of States which had accepted the Amendments prior to the entry into force of the Amendments. *See chapter IX.1 for the complete list of Participants, Members of the World Health Organization, for which the above amendments are in force, pursuant to article 73 of the Constitution. Participant1,2,3,4 Acceptance(A) Participant1,2,3,4 Acceptance(A) Afghanistan..................................................11 Aug 1960 A India.............................................................23 Feb 1960 A Albania.........................................................27 Jul 1960 A Iran (Islamic Republic of)............................ 2 May 1960 A Australia.......................................................12 Aug 1959 A Iraq...............................................................25