Monumenta Issn: 1857-999Х

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian by Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian By Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg One topic that regularly recurs in the scholarship on modern warfare is combat cohesion and motivation. Many volumes have been published on these topics, and there is no sign that this interest might abate any time soon. That interest has only rarely filtered down to scholarship of the ancient and late antique worlds, however. 1 The sixth century is well suited to analyses of these issues given the abundance of varied and high quality evidence, despite the lack of attention given the subject by modern scholars. This chapter seeks to remedy this by offering an introduction to combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century. It forms the second half of a two-part project on the subject, and the core this project is the evidence of Procopius. 2 Procopius describes more than thirty battles or sieges from the age of Justinian,3 and his battle narratives have been the subject of a good deal of research. 4 Yet there is much more work to do on sixth-century combat and our understanding Procopius’ value as a source for military history. By introducing the subject of combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century, this paper seeks to move the discussion forward. 5 The first part of this paper will be concerned with motivation, and will explore the much discussed “ratio of fire” and its applicability in an ancient context, the presumed bellicosity of some soldiers that many of our sources hint at, and the role of fear in motivating soldiers to fight and to maintain their cohesion. -

(2019), the Vardar River As a Border of Semiosphere – Paradox Of

Geographia Polonica 2019, Volume 92, Issue 1, pp. 83-102 https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0138 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE VARDAR RIVER AS A BORDER OF SEMIOSPHERE – PARADOX OF SKOPJE REGENERATION Armina Kapusta Urban Regeneration Laboratory Institute of Urban Geography and Tourism Studies Faculty of Geographical Sciences University of Łódź Kopcińskiego 31, 90-142 Łódź: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract As suggested by its etymology, regeneration usually carries positive connotations while its negative aspects tend to be belittled. However, any renewal results in major morphological, physiognomic, functional or social changes, which imply changes in the meanings encoded in space. These transformations are not always welcome and they may lead to public discussions and conflicts. Skopje 2014 is a project within which such controversial transformations have been taking place. The area surrounding the Vardar River and its banks plays a major role here. On the river banks monumental buildings were erected, bridges over the river were modernised and new ones, decorated with monuments, were built for pedestrians. Bridges can be considered a valuable component of any urban infrastructure as they link different parts of a settlement unit (in the case of Skopje – left (northern) bank and the right (southern) bank; Albanian and Macedonian), improve transport, facilitate trade and cultural exchange. In this context, referring to Lotman’s semiosphere theory, they may become borders of semiotic space, which acts as a filter that facilitates the penetration of codes and cultural texts. Yet, in multicultural Skopje meanings attached to bridges seem to lead to social inequalities as they glorify what is Macedonian and degrade the Albanian element. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy o f the original document. While the most advai peed technological meant to photograph and reproduce this document have been useJ the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The followini explanation o f techniques is provided to help you understand markings or pattei“ims which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target" for pages apparently lacking from die document phoiographed is “Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This| may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Wheji an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is ar indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have mo1vad during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. Wheh a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in 'sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to righj in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until com alete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, ho we ver, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "ph btographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

109 I. INTRODUCTION the Strategikon Is a Roman Military

A C T A AThe R SCTra HT egikonA E Oa S La SOource G I —C SlavA SC andA Ra varP SA… T H I C109 A VOL. LII, 2017 PL ISSN 0001-5229 ŁUKASZ Różycki THE STRATEGIKON AS A SOURCE — SLAVS AND AVARS IN THE EYES OF PSEUDO-MAURICE, CURRENT STATE OF RESEARCH AND FUTURE RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES ABSTRACT Ł. Różycki 2017. The Strategikon as a source — Slavs and Avars in the eyes of Pseudo-Maurice, current state of research and future research perspectives, AAC 52:109–131. The purpose of the piece The Strategikon as a source — Slavs and Avars in the eyes of Pseudo- Maurice, current state of research and future research perspectives is to demonstrate what the author of Strategikon knew about the Slavs and Avars and review the state of research on the chapter of the treatise that deals with these two barbarian ethnicities. As a side note to the de- scription of contemporary studies of Strategikon, the piece also lists promising areas of research, which have not yet received proper attention from scholars. K e y w o r d s: Migration Period; Early Middle Ages; Balkans; Byzantium; Strategicon; Strategikon; Emperor Maurice; Slavs; Avars Received: 15.03.2017; Revised: 30.07.2017; Revised: 19.10.2017; Revised: 29.10.2017; Accepted: 30.10.2017 I. INTRODUCTION The Strategikon is a Roman military treatise, written at the end of the 6th or the beginning of the 7th century. It is one of the seminal sources not only on East Roman military history but also on the Slavs, the Avars and other peoples neighboring the Empire at the onset of the Middle Ages. -

Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2084-140X.01.08 Studia Ceranea 1, 2011, p. 127-142 Teresa Wolińska (Łódź) Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters So engrossed were they in the wild passion that the entire city was filled with their voices and wild screaming. (...) Some perched higher behaving in decorously, others located in the market shouted at the horsemen, applauded them and screamed more than others.1 The above characteristics of the Byzantine supporters, recorded in the fourth century by the bishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, could as well, after minor adjustments, be applied to describe today’s football fans .Support in sport is certainly one of the oldest human passions. It is only the disciplines captivating audiences that change. In the ancient Roman Empire, bloody spectacles had the same role as today’s world league games – gladiatorial combat and fights withwild animals2. However, they were incompatible with Christian morality, and as such, they were gradually eliminated as the Christianization progressed3 .Their place was taken by hippodrome racing, particularly chariot racing . Residents of the imperial capital cheered the chariot drivers, whose colourful outfits signaled their membership in a particular circus faction . In the empire, there were four factions (demes), named after the colours of their outfits worn by runners and drivers representing them, the Blues, Greens, Whites and Reds4 .Each faction had 1 Joannes Chrysostomos, Homilia adversus eos qui ecclesia relicta ad circenses ludos et theatra transfugerunt, 1, [in:] PG, vol . LVI, col . 263 . 2 H .G . Saradi, The Byzantine City in the Sixth Century . Literary Images and Historical Reality, Athens 2006, p . -

Very Short History of the Macedonian People from Prehistory to the Present

Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Prehistory to the Present By Risto Stefov 1 Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Pre-History to the Present Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2008 by Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................4 Pre-Historic Macedonia...............................................................................6 Ancient Macedonia......................................................................................8 Roman Macedonia.....................................................................................12 The Macedonians in India and Pakistan....................................................14 Rise of Christianity....................................................................................15 Byzantine Macedonia................................................................................17 Kiril and Metodi ........................................................................................19 Medieval Macedonia .................................................................................21 -

Slavs and Avars (500–800)

chapter 4 East European Dark Ages: Slavs and Avars (500–800) In response to repeated raids into their lands “on the far side of the river” Danube, the Slavs, thought it over among themselves, and said: “These Romani, now that they have crossed over and found booty, will in the future not cease com- ing over against us, and so we will devise a plan against them.” And so, therefore, the Slavs, or Avars, took counsel, and on one occasion when the Romani had crossed over, they laid ambushes and attacked and defeat- ed them. The aforesaid Slavs took the Roman arms and the rest of their military insignia and crossed the river and came to the frontier pass, and when the Romani who were there saw them and beheld the standards and accouterments of their own men they thought they were their own men, and so, when the aforesaid Slavs reached the pass, they let them through. Once through, they instantly expelled the Romani and took pos- session of the aforesaid city of Salona. There they settled and thereafter began gradually to make plundering raids and destroyed the Romani who dwelt in the plains and on the higher ground and took possession of their lands.1 Thus described Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in the mid-10th century, the migration of the Slavs from their lands to the Balkans. The story is placed chronologically “once upon a time,” at some point between the reigns of Emperors Diocletian, who brought the “Romani” to Dalmatia, and Heraclius. There is no reason to treat the story as a trustworthy historical account, but it is clear that it is meant to explain the particular situation of Salona and the former province of Dalmatia.2 No historian seems to have noticed so far that Emperor Constantine VII’s account is, after all, the only written testimony of 1 Constantine Porphyrogenitus, On the Administration of the Empire 29, pp. -

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

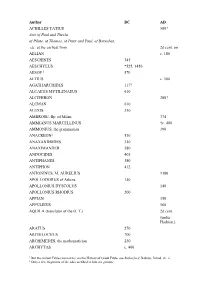

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3 Sasanika Sources History of Menander the Guardsman (Menander Protector) was written at the end of the sixth century CE by a minor official of the Roman/Byzantine court. The original text is in Greek, but has survived only in a fragmentary form, quoted in compilations and other historical writings. The author, Menander, was a native of Constantinople, seemingly from a lowly class and initially himself not worthy of note. In a significant introductory passage, he courageously admits to having undertaken the writing of his History (’ st a) as a way of becoming more respectable and forging himself a career. He certainly was a contemporary and probably an acquaintance of the historian Theophylact Simocatta and worked within the same court of Emperor Maurice. His title of “Protector” seems to suggest a military position, but most scholars suspect that this was only an honorary title without any real responsibilities. Menander’s history claims to continue the work of Agathias and so starts from the date that Agathias left off, namely AD 557. His style of presentation, if not his actual writing style, are thus influenced by Agathias, although he seems much less partial than the former in presentation of the events. He seems to have had access to imperial archives and reports and consequently presents us with a seemingly accurate version of the events, although at time he might be exaggerating some of his facts. The following is R. C. Blockley’s English translation of the fragments 6.1-3 of Menander Protector’s History, which deals directly with the Sasanian-Roman peace treaty of 562 and provides us with much information about the details of negotiations that took place around this treaty. -

Piotrkowskie Zeszyty Historyczne, T. 15 (2014) ______

Piotrkowskie Zeszyty Historyczne, t. 15 (2014) _______________________________________________________________ Georgi N. Nikolov, Samostojatelni i polusamostojatelni vladenija văv văzobnovenoto Bălgarsko carstvo (kraja na XII – sredata na XIII v.), IK „Gutenberg”, Sofija 2011, ss. 255 Recenzowana ksiąŜka wyszła spod pióra Georgiego N. Nikołowa, znanego bułgarskiego historyka, autora wielu prac dotyczących róŜ- nych aspektów średniowiecznych dziejów Bułgarii1. Tym razem przedmiotem jego rozwaŜań są przejawy separatyzmu na ziemiach bułgarskich od czasów odrodzenia Bułgarii po powstaniu Teodora- Piotra i Asena po połowę wieku XIII. W obrębie jego rozwaŜań zna- leźli się moŜni, którzy, w interesującym go okresie, zbudowali samo- dzielne lub na wpół samodzielne władztwa. Badacz stara się odtwo- rzyć ich losy, zasięg terytorialny posiadłości, którymi zarządzali, wreszcie ocenić znaczenie ich działalności w kontekście interesów państwowości bułgarskiej. Jego szczególną uwagę budzą równieŜ rezydencje i twierdze, które znalazły się w rękach separatystów (m.in. Wielki Presław, Prosek, Cepina, Melnik). Cele, które postawił sobie G.N. Nikołow, nie były łatwe do zrealizowania ze względu na skąpość i charakter materiałów źródłowych, którymi dysponują badacze zajmujący się tymi zagadnieniami. Mimo to bułgarskiemu uczonemu udało się, w moim przekonaniu, zbudować pełny, na ile było to moŜliwe, obraz ruchów separatystycznych na ziemiach buł- garskich od końca XII po połowę XIII w. Praca podzielona jest na pięć podstawowych części. W pierwszej, zatytułowanej Apanažni vladenija i separatizăm v Bălgarskija seve- roiztok (s. 59–69), Autor przedstawia dwie samodzielne czy częściowo samodzielne struktury, które istniały w północno-wschodniej Bułga- 1 Dorobek G.N. Nikołowa obejmuje sto kilkadziesiąt pozycji, spośród których szczególną uwagę trzeba zwrócić na ksiąŜkę: Centralizăm i regionalizăm v ranno- srednovekovna Bălgarija ( kraja na VII-načaloto na XI v.), Sofija 2005, ss. -

Christianity in the Balkans

STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY VOL. I. MATTHEW SPINKA ROBERT HASTINGS NICHOLS Editors a TT- , H »80-6 A H istory of CHRISTIANITY IN THE BALKANS "Y. ^ \ A STUDY IN THE SPREAD OF BYZANTINE CULTURE \ X # 0% \ AMONG THE SLAVS • pi- . ':'H, \ - ■ V V"\ \ By MATTHEW SPINKA THE CHICAGO THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY a y THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CHURCH HISTORY CHICAGO, ILL. Copyright 1933 by The American Society of Church History All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America DNU072 TABLE OF CONTENTS ❖ ♦> ❖ ❖ The Ruin of Graeco-Roman and the Rise of Slavic Balkan Christianity........................ 1 Bulgarian Christianity after the Conversion of Boris................. 37 Bulgarian Patriarchate of the First Bulgarian Empire............. 57 Serbian Christianity Before the Time of St. Sava....... ............. 73 The Bulgarian Church of the Second Empire.............................. 91 The Rise and Fall of the Serbian Church..................................129 Bogomilism in Bosnia and Hum................... 157 Epilogue ............... 185 Selected Bibliography .....................................................................189 Index .................................................................................................193 t PREFACE No one can be more conscious of the limitations of this work than the author himself. He was constantly impressed with the fact that all too little attention has been paid hither to to the subject even by scholars of the Balkan nations, not to speak of non-Slavic historians; consequently, much preliminary pioneering work had to be done. Much yet remains to be accomplished; but the restricted scope of this undertaking as well as the paucity of source material per taining to the early history of the Balkan peninsula com bined to make the treatment actually adopted expedient. In gathering his material, the author spent some time during the summer of 1931 in the Balkans.