Canadian Indian Policy and Development Planning Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Histoire De La Russie & Des Peuples Slaves I Les Peuples Slaves

Lundi, le 4 février 2013 Office de consultation publique de Montréal 1550, rue Metcalfe, bureau 1414 Montréal, Québec H3A 1X6 Tel: 514-872-8510 Courriel: [email protected] De Belles Valeurs à Promouvoir L’entreprise que j’ai créée, eucantravel.ca, œuvre dans le domaine des télécommunications internet, en misant sur le tourisme comme orientation principale. Ainsi, ayant pris soin de noter quelques points intéressants, lors de votre 3e séance d’information, j’aimerais vous proposer un document de référence, que j’ai intitulé: “Points de repères sur la Russie, l’Ukraine et le Canada” afin de voir à l’amélioration de votre vision. Dans celui-ci, je vous livre une vision d’est en ouest de ce que fut le développement de l’Amérique, quels en fut ses fondements mêmes, en y intégrant l’histoire d’un autre peuple nordique, que nous retrouvons de l’autre côté de l’océan Pacifique, soit le continent des peuples slaves (la Russie, l’Ukraine, etc.). Le but de cet exercice étant de revivifier une fierté nordique que nous semblons avoir mise de côté. De par la vision que je vous propose, vous pourrez constater que les 2 continents ici présentés possèdent des histoires qui se chevauchent sur plusieurs points, nommons par exemple, la traite des fourrures, laquelle activité commerciale fut à la base même de la création du Canada. Nous pouvons ainsi voir que 2 compagnies majeures ont su s’élever, soit: la Hudson Bay Company (en 1668) au Canada et la Russian American Company (en 1779) en Russie. A cela, nous pouvons également parler de la création des 2 compagnies de chemins de fer nationaux, lesquelles furent le Canadien Pacifique (en 1881) au Canada, qui est devenu VIA Rail pour le transport des passagers, et le chemin de fer Transsibérien (en 1891) en Russie. -

Theorizing the Origins and Advancement of Indigenous Activism: the Case of the Russian North a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Theorizing the Origins and Advancement of Indigenous Activism: The Case of the Russian North A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Irina L. Stoyanova Master of Science George Mason University, 2006 Director: Peter J. Balint, Professor of Environmental Policy Department of Public and International Affairs Summer Semester 2009 George Mason University Fairfax, VA DEDICATION За Лидия и Любомир ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first wish to express my gratitude and appreciation to the professors who guided my thought and helped me complete this research. I would foremost like to thank my Advisor and Chair of my dissertation committee, Dr. Peter J. Balint. Without his invaluable intellectual guidance, patience, constructive reviewing and critiquing this dissertation would not have been realized. Similarly, special thanks go to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan A. Crate, Dr. Lee M. Talbot, and Dr. Thomas R. Williams. They have all been extremely generous with their time and have offered me critical insights to this project. I also like to thank the Environmental Science and Policy Department for the financial support during my first years of graduate studies and especially the two Graduate Programs Coordinators – Dr. Ron Stewart and Mrs. Annaliesa Guilford – who expertly assisted me through all the administrative obstacles. Very special thanks are due to Jessica and Andrew Stowe who provided me with a much needed quiet environment where I can do my writing. During the last three years of my graduate studies, they offered me more than just a room within their home; they became a second family for me. -

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada This report is in the public domain. Anyone may, without charge or request for permission, reproduce all or part of this report. 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Website: www.trc.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future : summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Issued also in French under title: Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir, sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in printed form. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-660-02078-5 Cat. no.: IR4-7/2015E-PDF 1. Native peoples--Canada--Residential schools. 2. Native peoples—Canada--History. 3. Native peoples--Canada--Social conditions. 4. Native peoples—Canada--Government relations. 5. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 6. Truth commissions--Canada. I. Title. II. Title: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. E96.5 T78 2015 971.004’97 C2015-980024-2 Contents Preface ........................................................................................................ -

The First Nations Struggle to Be Recognized

THE FIRST NATIONS STRUGGLE TO BE RECOGNIZED aties in the g Tre Cla hin ssro ac R C E G U I D om Te O U E F E S O R R G T Y R A A E D R T E 5 A August 2008 The Office of the Treaty Commissioner in partnership with FIELD TEST DRAFT The First Nations Struggle to Be Recognized: Teaching Treaties in the Classroom, A Treaty Resource Guide for Grade 5 © 2008 All rights reserved. This book is to be used for educational purposes only and is not intended for resale. Permission to adapt the information contained herein for any other purpose requires permission in writing from the Office of the Treaty Commissioner. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Teaching treaties in the classroom : a treaty resource guide for kindergarten to grade 6 / Office of the Treaty Commissioner. Contents: Since time immemorial : a treaty resource guide for kindergarten — The lifestyles of the First Nations peoples before and after the arrival of the newcomers : a treaty resource guide for grade 1 — The numbered treaties in Saskatchewan : a treaty resource guide for grade 2 — The First Nations and the newcomers settle in what is now known as Saskatchewan : a treaty resource guide for grade 3 — The Indian Act of 1876 was not part of treaty : a treaty resource guide for grade 4 — The First Nations struggle to be recognized : a treaty resource guide for grade 5 — Revival of the treaty relationship, living in harmony : a treaty resource guide for grade 6 ISBN 978-0-9782685-1-0 (kindergarten).— ISBN 978-0-9782685-2-7 (grade 1). -

Assembly of First Nations – Our Story

Assembly of First Nations – Our Story The story of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is one that remains unknown to most Canadians. It is the story that is lived each day by the First Nations peoples of Canada. It is the story of a struggle for self-determination and human dignity. It is a story that must be told. Many Canadians are unaware of the enormous problems that the First Nations peoples have faced on the road to political recognition in this country. Few Canadians realize that the First Nations peoples are identified in the Constitution as one of the founding nations of Canada, along with the English and French. Few Canadians are aware that up until the 1983-87 First Ministers Conference on Aboriginal Rights, the First Nations People were excluded from taking part in the Constitutional developments of Canada. First Nations peoples have had to deal with conditions of extreme poverty and isolation, and vast geographical dispersion, within the tremendous diversity of aboriginal cultures, languages, and political ideologies. Improved communications and transportation have allowed First Nations Peoples to begin to talk to each other, to the rest of Canada, and to the rest of the world. These relatively recent developments have meant that the First Nations Peoples have had to work harder and faster in order to catch up with the federal and provincial governments in the fields of political knowledge, political reality, and especially in political expertise. The years of being excluded from Canada's formal political process has left First Nations Peoples with an incredible void to fill just in order to attain a level of political, social, and legal knowledge that is on par with other groups in Canadian society. -

Stewart Raby Collection

Box 1 Front to back F1 “Proposed revisions to Indian Act for discussion purposes” Association of Iroquois and allied Indians 1975 – “Loosening the Indian Act” article by L.J. Ryan 1967 – “A proposal for a new Indian Act for discussion only” by Paul Jenson 1973 – “Indian and income tax legislation” notes from the Annual meeting of the National Indian Brotherhood 1972 F2 Federation of Saskatchewan Indians memorandum “Convention on re-organizing of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians (fourth draft)” 1981 – “Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations’ Convention” 1982 – Federation of Saskatchewan Indians “proposal for the funding of a five year research and development project for the establishment of an Indian Justice System in Saskatchewan” draft – “Explanation for the provisional charter of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations’ Chiefs Council” 1982? – “The Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations’ provisional charter” draft – Saskatoon district Chiefs “Convention” – “Reorganization of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians Agency Convention” F3 Native Council of Canada press releases, letters, Gloria George – “Copy of a surrender to the Crown 10th July 1827” regarding the Chippewa Nation – Historical documentation regarding the Iroquois Indians (St. Regis) and their treaties F4 Department of Indian Affairs “Index to schedule of Indian reserves in British Columbia” 1902 – “Schedule of Indian reserves in the Dominion : British Columbia” – “Indian reserve acreage per capita : by Bands” 1970 – “The defence of James Bay – an emergency for all Native people and other residents of North America” by Walter Taylor 1973 – “Human problems in the development of the James Bay Hydro Project” by Richard J. Preston 1971? – “James Bay : last massacre of Indian rights” article by George W. -

Marten Falls First Nation the Great Reset

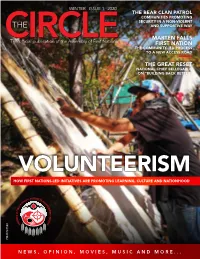

WINTER ISSUE 1 2020 THE BEAR CLAN PATROL COMMUNITIES PROMOTING SECURITY IN A NON-VIOLENT THE AND SUPPORTIVE- WAY MARTEN FALLS CIRCLEThe official publication of the Assembly of First Nations CIRCLE FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY-LED PROCESS TO A NEW ACCESS- ROAD THE GREAT RESET NATIONAL CHIEF BELLEGARDE ON “BUILDING BACK BETTER” VOLUNTEERISM HOW FIRST NATIONS-LED INITIATIVES ARE PROMOTING LEARNING, CULTURE AND NATIONHOOD PM40787580 NEWS, OPINION, MOVIES, MUSIC AND MORE... Winter Issue 1 2020 THE CIRCLEThe official publication of the Assembly of First Nations 38 About the AFN The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) represents First Nations citizens in Canada. This means we work for you. All our efforts are mandated by leaders from across the country and the priorities for action set by the Chiefs-in-Assembly. In AFN’s The Circle, learn more about the role of the National Chief, Regional Chiefs, councils, committees, assemblies and the AFN staff. We look forward to hearing your feedback. 43 AFN Working This is a section on progress happening in the various sectors at the AFN through its work with Chiefs’ committees, First Nations citizens, tribal councils, professionals and people on the frontline. From environment and emergency services to economic development, health and language, these are the FEATURES updates on how we’re driving change based on the 65 The Great Reset priorities of First Nations. Perry Bellegarde on the unprecedented opportunity to re-align core values around the world 80 Art & Media Art, film, literature and music are all here rolled into 75 Marten Falls Community Leads one section. -

Big Bear's Treaty

J O U R N A L CONTENTS 11 It is our pleasure to make this article from Inroads 11 available to you free of charge. FRONT MATTER Introducing Inroads 2 Letter to the editor 4 In answer to Baum’s query John Richards 6 An inquiry into the consequences of the Magna Carta and the Charter of Rights Please consider a subscription to help us Harvey Schachter 11 Richler remembered CITIES to continue to provide timely, thought- Andrew Sancton 25 Cities are too important for municipalities alone provoking articles in print – and often on- Rae Murphy 33 Toronto: Canada’s sleeping giant John Richards 44 Saturday afternoon in East Vancouver line – to readers across Canada and beyond. Henry Milner and Pierre Joncas 49 Montreal: Getting through the megamerger On the next page, you will On the last page, you will find BILINGUAL CITIES Philip Resnick 65 Language, identity, citizenship find more information about information about subscribing. Charles Castonguay 71 Nation building and anglicization in Canada’s capital region what’s in the current issue of You can print it out or just send John Richards 87 Calcutta and Dhaka: A tale of two cities Inroads. us an email or give us a call. Kenneth McRae 95 Helsinki: Snapshots in time FIRST NATIONS Jean Allard 108 Big Bear’s Treaty: The road to freedom A major excerpt from the yet-unpublished manuscript with a foreword by Gordon Gibson g{tÇ~áA POVERTY Arthur Milner, chair 170 Inroads roundtable: Rick August, Ken Battle, Harvey Bostrom, Louis Grignon, Carol LaPrairie, Kevin Little, Sharon Manson Singer and Marie-France Raynault AND MORE A WORD ABOUT PRINTING THIS ARTICLE: These pages are intended to print Reg Whitaker 187 The flight from politics: Why neither Left nor Right play the game any more on legal (8.5 x 14 inch) paper, two pages per sheet, in a horizontal landscape. -

Public Expressions of First Nations Protest in Canada's

PUBLIC EXPRESSIONS OF FIRST NATIONS PROTEST IN CANADA’S SIXTIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In History University of Regina By Brian Eric Warren Regina, Saskatchewan March 2020 Copyright 2020: Brian Warren UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Brian Eric Warren, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in History, has presented a thesis titled, Public Expressions of First Nations Protest in Canada’s Sixties, in an oral examination held on March 17, 2020. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: *Dr. John Meehan, University of Sudbury Supervisor: Dr. Ken Leyton-Brown, Department of History Committee Member: Dr. Philip Charrier, Department of History Committee Member: Dr. James Daschuk, Faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies Chair of Defense: Dr. Dongyan Blachford, Department of International Languages *via Teleconference i Abstract Much of the literature about modern First Nations activism in Canada has left the impression that it began, in earnest, in protest of the federal government’s controversial 1969 White Paper. As a result, several significant and well-publicized expressions of First Nations protest in the preceding decade, have been widely ignored. This thesis explores the growth and diversification of First Nations protest, from the eve of the sixties, through the White Paper backlash, to demonstrate how the groundwork for future activism, was laid amid the political foment of the sixties. -

Plain Talk 26

26 An Overview plain The Assembly of First Nations talk it’s our time... An Overview The Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde Perry Bellegarde was named AFN National Chief on December 10, 2014. He has spent his entire adult life putting into practice his strong beliefs in the laws and traditions instilled in him by the many Chiefs and Elders he has known over the years. Passionate about making measureable progress on the issues that matter most to First Nations people, National Chief Bellegarde is a strong advocate for the implementation of Inherent Aboriginal and Treaty Rights. Widely known as a consensus builder with a track record of accomplishment, he brings community people, leaders, Chiefs and Elders together to focus on working cooperatively to move issues forward. National Chief Bellegarde’s candidacy for National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations was based on a vision that includes establishing processes for self-determination; recognition of inherent Aboriginal and Treaty rights; the revitalization and retention of indigenous languages; and establishing a new relationship with the Crown – one that removes the long-standing 2% cap on federal funding. National Chief Bellegarde is from the Little Black Bear First Nation, Treaty 4 Territory. He served as Chief of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, Saskatchewan Regional Chief for the Assembly of First Nations, Tribal Chair of the Touchwood-File Hills-Qu’Appelle Tribal Council, Councillor for the Little Black Bear First Nation, and Chief of Little Black Bear First Nation. In 1984, Bellegarde became the first Treaty Indian to graduate from the University of Regina with a Bachelor of Administration. -

'Rise up - Make Haste - Our People Need Us!' : Pan-Indigenous Activism in Canada and the United States, 1950 to 1975

'Rise up - make haste - our people need us!' : Pan-Indigenous Activism in Canada and the United States, 1950 to 1975 by Karine R. Duhamel A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2013 by Karine R. Duhamel Table of Contents Abstract iii Acknowledgments iv Dedication v Timeline of Key Events vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 36 Formulating a pan-Indigenous Agenda: Citizenship and Liberalism after World War II Chapter 2: 86 'A Tough Horse to Ride': The Challenge of Organizational Politics in the Rights Era Chapter 3: 158 'Indians in the City': Indigenous Responses to the Challenges of Urbanization Chapter 4: 216 'We were just trying to survive': The Challenges of Indigenous Politics on Canadian Reserves Chapter 5: 258 'I struggle along anyway': The American Reservation System and 1960s Revival Chapter 6: 293 'Rise up – make haste – our people need us': Activism and the Baby Boom Generation Chapter 7: 346 'Your little girl and mine': Gendered Politics and Indigenous Women's Organizing Conclusion 401 Bibliography 414 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the period of pan-Indigenous activism in Canada and in the United States between 1950 and 1975. The rights era in both countries presented important challenges for both legislators and for minority groups. In a post-war context increasingly concerned with equality and global justice, minority groups were uniquely positioned to exact from the government perhaps greater concessions than ever before. For Indigenous groups, however, the potential of this period delivered only in part due to initiatives like the Great Society and the Just Society which, while claiming to offer justice for Indigenous people, threatened them as perhaps never before, by homogenizing Indigenous people and their demands with those of other minority groups. -

Sasktel Indigenous Youth Awards Honour Outstanding Young Achievers

JUNE 2017 VOLUME 20 - NUMBER 6 FREE Centennial baby hits another milestone Kara ffolliott will soon turn 50 on July 1. She is Canada’s first Centennial Baby girl, born at 12:18 a.m. in Regina, Saskatchewan. She currently lives in Abbotsford, B.C. (Photo courtesy of Kara ffolliott) THREE DEGREES! Dana Carriere participated in the U of S powwow and had lots of reasons to celebrate. - Page 3 YOUTH LAUREATE Josh Butcher’s hard work is paying off and he’s now enrolled in the College of Medicine.. - Pag e 7 RUNNING FOR DAD Landon Sasakamoose recently lost his father but he isn’t letting that tragedy stand in his way. - Page 14 CAPTURING STORIES Trudy Stewart’s documentary, From Up North, has captured some painful stories . - Page 20 BASEBALL ICON The baseball community has found an ideal way to honour the memory of Joe Gallagher. - P age 21 National Aboriginal Day Edition By K.D. Sawatzky “My Mom was in labour for like 38 hours and Coming In July - Graduation Issue For Eagle Feather News they made her hold off so that I could be the first baby Every year, when her birthday comes around, girl born in Canada,” she said. Kara ffoliott’s parents told her about the day she was CPMA #40027204 born and how special it was. • Continued on Page 2 Eagle Feather News JUNE 2017 M2 ove over Pamela Anderson, Kara was number one • Continued from Page One ford, B.C. and have two grown children. Despite their age difference of 17 years, ganizers asking them if they were going “I was born at (12:18 a.m.).