Click Here to Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Honour of One Is the the Remarkable Contributions of These First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors Table of Contents of Table

The Honour of One is the The Remarkable Contributions of these First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Introduction 4 William (Bill) Ronald Reid 8 George Manuel 10 Margaret Siwallace 12 Chief Simon Baker 14 Phyllis Amelia Chelsea 16 Elizabeth Rose Charlie 18 Elijah Edward Smith 20 Doreen May Jensen 22 Minnie Elizabeth Croft 24 Georges Henry Erasmus 26 Verna Jane Kirkness 28 Vincent Stogan 30 Clarence Thomas Jules 32 Alfred John Scow 34 Robert Francis Joseph 36 Simon Peter Lucas 38 Madeleine Dion Stout 40 Acknowledgments 42 4 THE HONOUR OF ONE IntroductionIntroduction 5 THE HONOUR OF ONE The Honour of One is the Honour of All “As we enter this new age that is being he Honour of One is the called “The Age of Information,” I like to THonour of All Sourcebook is think it is the age when healing will take a tribute to the First Nations men place. This is a good time to acknowledge and women recognized by the our accomplishments. This is a good time to University of British Columbia for share. We need to learn from the wisdom of their distinguished achievements and our ancestors. We need to recognize the hard outstanding service to either the life work of our predecessors which has brought of the university, the province, or on us to where we are today.” a national or international level. Doreen Jensen May 29, 1992 This tribute shows that excellence can be expressed in many ways. -

®V ®V ®V ®V ®V

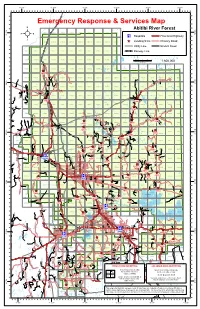

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 82°0'W 81°30'W 81°0'W 80°30'W 80°0'W 79°30'W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ' N ' 0 0 3 ° 3 ! ° 450559 460559 470559 480559 490559 500559 510559 520559 530559 0 0 5 5 ! v® Hospitals Provincial Highway ! ² 450558 460558 470558 480558 490558 500558 510558 520558 530558 ^_ Landing Sites Primary Road ! ! ! ! Utility Line Branch Road 430557 440557 450! 557 460557 470557 480557 490557 500557 510557 520557 530557 Railway Line ! ! 430556 440556 450556 460556 470556 480556 490556 500556 510556 520556 530556 5 2.5 0 5 10 15 ! Kilometers 1:800,000 ! ! ! ! 45! 0! 555 430555 440555 460555 470555 480555 490555 500555 510555 520555 530555 540555 550555 560555 570555 580555 590555 600555 ! ad ! ! o ^_ e R ak y L dre ! P u ! A O ! it t 6 t 1 e r o 430554 440554 450554 460554 470554 480554 490554 500554 510554 520554 530554 540554 550554 560554 570554 580554 590554 600554 r R R d! o ! d a y ! a ad a p H d o N i ' N o d R ' 0 ! s e R n ° 0 i 1 ° ! R M 0 h r d ! ! 0 u c o 5 Flatt Ext a to red ! F a a 5 e o e d D 4 R ! B 1 430553 440553 45055! 3 460553 470553 480553 490553 500553 510553 520553 530553 540553 550553 560553 570553 580553 590553 600553 R ! ! S C ! ! Li ttle d L Newpost Road ! a o ! ng ! o d R ! o R a a o d e ! R ! s C ! o e ! ! L 450552! ! g k i 430552 440552 ! 460552 470552 480552 490552 500552 510552 520552 530552 540552 550552 560552 570552 580552 590552 600552 C a 0 e ! n ! L U n S 1 i o ! ! ! R y p L ! N a p l ! y 8 C e e ^_ ! r k ^_ K C ! o ! S ! ! R a m t ! 8 ! t ! ! ! S a ! ! ! w ! ! 550551 a ! 430551 440551 450551 -

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit Kapuskasing Iroquois Falls Hearst Timmins Porcupine Cochrane Moosonee Hornepayne Matheson Smooth Rock Falls Population Profile Foyez Haque, MBBS, MHSc Public Health Epidemiologist published by: Th e Porcupine Health Unit Timmins, Ontario October 2009 ©2009 Population Profile - 2006 Census Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to those without whose support this Population Profile would not be published. First of all, I would like to thank the management committee of the Porcupine Health Unit for their continuous support of and enthusiasm for this publication. Dr. Dennis Hong deserves a special thank you for his thorough revision. Thanks go to Amanda Belisle for her support with editing, creating such a wonderful cover page, layout and promotion of the findings of this publication. I acknowledge the support of the Statistics Canada for history and description of the 2006 Census and also the definitions of the variables. Porcupine Health Unit – 1 Population Profile - 2006 Census 2 – Porcupine Health Unit Population Profile - 2006 Census Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 1 Preface . 5 Executive Summary . 7 A Brief History of the Census in Canada . 9 A Brief Description of the 2006 Census . 11 Population Pyramid. 15 Appendix . 31 Definitions . 35 Table of Charts Table 1: Population distribution . 12 Table 2: Age and gender characteristics. 14 Figure 3: Aboriginal status population . 16 Figure 4: Visible minority . 17 Figure 5: Legal married status. 18 Figure 6: Family characteristics in Ontario . 19 Figure 7: Family characteristics in Porcupine Health Unit area . 19 Figure 8: Low income cut-offs . 20 Figure 11: Mother tongue . -

(De Beers, Or the Proponent) Has Identified a Diamond

VICTOR DIAMOND PROJECT Comprehensive Study Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Overview and Background De Beers Canada Inc. (De Beers, or the Proponent) has identified a diamond resource, approximately 90 km west of the First Nation community of Attawapiskat, within the James Bay Lowlands of Ontario, (Figure 1-1). The resource consists of two kimberlite (diamond bearing ore) pipes, referred to as Victor Main and Victor Southwest. The proposed development is called the Victor Diamond Project. Appendix A is a corporate profile of De Beers, provided by the Proponent. Advanced exploration activities were carried out at the Victor site during 2000 and 2001, during which time approximately 10,000 tonnes of kimberlite were recovered from surface trenching and large diameter drilling, for on-site testing. An 80-person camp was established, along with a sample processing plant, and a winter airstrip to support the program. Desktop (2001), Prefeasibility (2002) and Feasibility (2003) engineering studies have been carried out, indicating to De Beers that the Victor Diamond Project (VDP) is technically feasible and economically viable. The resource is valued at 28.5 Mt, containing an estimated 6.5 million carats of diamonds. De Beers’ current mineral claims in the vicinity of the Victor site are shown on Figure 1-2. The Proponent’s project plan provides for the development of an open pit mine with on-site ore processing. Mining and processing will be carried out at an approximate ore throughput of 2.5 million tonnes/year (2.5 Mt/a), or about 7,000 tonnes/day. Associated project infrastructure linking the Victor site to Attawapiskat include the existing south winter road and a proposed 115 kV transmission line, and possibly a small barge landing area to be constructed in Attawapiskat for use during the project construction phase. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

Final Report on Facilitated Community Sessions March 2020

FINAL REPORT ON FACILITATED COMMUNITY SESSIONS MARCH 2020 MCLEOD WOOD ASSOCIATES INC. #201-160 St David St. S., Fergus, ON N1M 2L3 phone: 519 787 5119 Selection of a Preferred Location for the New Community Table Summarizing Comments from Focus Groups Contents The New Community – a Five Step Process .................................................................................... 2 Background: ................................................................................................................................ 2 Steps Leading to Relocation: ................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Steps Two and Three .......................................................................................... 4 Summary of the Focus Group Discussions: ............................................................................. 5 Appendix One: Notes from Moose Factory Meeting held November 26 2019…………………………17 Appendix Two: Notes from Moosonee Meeting held November 28 2019………………………………23 1 Selection of a Preferred Location for the New Community Table Summarizing Comments from Focus Groups The New Community – a Five Step Process Background: The MoCreebec Council of the Cree Nation was formed on February 6, 1980 to contend with economic and health concerns and the social housing conditions facing the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) beneficiaries that lived in Moose Factory and Moosonee. The JBNQA beneficiaries were mainly registered with three principal bands -

2.6 Settlement Along the Ottawa River

INTRODUCTION 76 2.6 Settlement Along the Ottawa River In spite of the 360‐metre drop of the Ottawa Figure 2.27 “The Great Kettle”, between its headwaters and its mouth, the river has Chaudiere Falls been a highway for human habitation for thousands of years. First Nations Peoples have lived and traded along the Ottawa for over 8000 years. In the 1600s, the fur trade sowed the seeds for European settlement along the river with its trading posts stationed between Montreal and Lake Temiskaming. Initially, French and British government policies discouraged settlement in the river valley and focused instead on the lucrative fur trade. As a result, settlement did not occur in earnest until the th th late 18 and 19 centuries. The arrival of Philemon Source: Archives Ontario of Wright to the Chaudiere Falls and the new British trend of importing settlers from the British Isles marked the beginning of the settlement era. Farming, forestry and canal building complemented each other and drew thousands of immigrants with the promise of a living wage. During this period, Irish, French Canadians and Scots arrived in the greatest numbers and had the most significant impact on the identity of the Ottawa Valley, reflected in local dialects and folk music and dancing. Settlement of the river valley has always been more intensive in its lower stretches, with little or no settlement upstream of Lake Temiskaming. As the fur trade gave way to farming, settlers cleared land and encroached on First Nations territory. To supplement meagre agricultural earnings, farmers turned to the lumber industry that fuelled the regional economy and attracted new waves of settlers. -

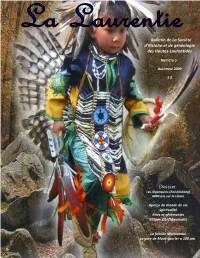

Lalaurentie05.Pdf

Bulletin de La Société d’histoire et de généalogie Bulletin de La Société d’histoire et de généalogie des Hautes-Laurentides des Hautes-Laurentides Volume 1, numéro 4 Mars 2009 5 $ Numéro 5 Automne 2009 5 $ Dossier Les Algonquins (Anishinàbeg) 6000 ans sur la Lièvre Aperçu du monde de vie Spiritualité Rites et cérémonies Kitigan Zibi (Maniwaki) La famille Mackanabé La gare de Mont-Laurier a 100 ans! 1 La Laurentie est publiée 4 fois par année par Sommaire La Société d’histoire et de généalogie des Hautes- Laurentides 385, rue du Pont, C.P. 153, Mont-Laurier (Québec) J9L 3G9 Propos à l’air libre 3 Téléphone : 819-623-1900 Télécopieur : 819-623-7079 Courriel : [email protected] Des nouvelles de votre Société 4 Site internet : www.genealogie.org/club/shrml/ Dossier : Les Anishinàbeg Heures d’ouverture : Du lundi au vendredi, de 9 h à 12 h et de 13 h à 17 h. Origine du mot Anishinàbe 7 Quelques mots Anishinàbeg 7 Rédacteur en chef : Gilles Deschatelets Répartition géographique 7 Équipe de rédaction : Aperçu du monde de vie 8 Suzanne Guénette, Louis-Michel Noël, Luc Coursol, Geneviève Piché, Heidi Weber. Le canot d’écorce 14 Spiritualité 16 Impression : Imprimerie L’Artographe Croyances 17 Conseil d’administration 2008-2009 : Quelques rites et cérémonies 18 Gilles Deschatelets (président), Shirley Duffy (vice-prési- Le collège Manitou 19 dente), Daniel Martin (trésorier), Gisèle L. Lapointe (secrétaire), Marguerite L. Lauzon (administratrice), La réserve de rivière Désert 20 Danielle Ouimet (administratrice). Des revendications 21 Nos responsables : Généalogie : Daniel Martin, Louis-Michel Noël Responsable administrative et webmestre : Suzanne Guénette Personne ressource : Denise Florant Dufresne. -

FINAL 2009 Annual Report

NEOnet 2009 Annual Report Infrastructure Enhancement Application Education and Awareness 2009 Annual Report Table of Contents Message from the Chair ..............................................................................................2 Corporate Profile........................................................................................................3 Mandate ....................................................................................................................3 Regional Profile ..........................................................................................................4 Catchment Area.......................................................................................................................................................5 NEOnet Team .............................................................................................................6 Organizational Chart..............................................................................................................................................6 Core Staff Members...............................................................................................................................................7 Leaving staff members..........................................................................................................................................8 Board of Directors ..................................................................................................................................................9 -

Les Fruits Du Sommet

GOÛTER LA VALLÉE Le territoire de la MRC de la Vallée-de-la-Gatineau offre une panoplie de produits agricoles locaux, frais et de qualité. Derrière ces produits se cachent des éleveurs, des maraîchers, des acériculteurs, des fermiers et des artisans passionnés, dont le travail et le savoir-faire ont de quoi nous rendre fiers. En achetant les produits de la Vallée-de- la-Gatineau, vous rendez hommage aux hommes et aux femmes qui les produisent et vous soutenez le dynamisme agricole de notre territoire. Plusieurs options s’offrent donc à vous : • Fréquentez les marchés publics ou les kiosques à la ferme à proximité • Privilégiez (ou demandez) des produits locaux au restaurant et partout où vous achetez des aliments • Mettez de la fraîcheur dans vos assiettes en privilégiant les produits locaux et saisonniers dans vos recettes • Expliquez à votre entourage les retombées de l’achat local • Et surtout, partagez votre enthousiasme pour les producteurs et les aliments d’ici ! Encourageons les producteurs de chez nous, achetons local ! PHOTOS DE LA COUVERTURE : 1) ÉRIC LABONTÉ, MAPAQ. 2) JOCELYN GALIPEAU 3) JONATHAN SAMSON 4) LINDA ROY 1 2 3 4 2 ÉVÉNEMENTS MARCHÉ AGRICOLE LES SAVEURS DE LA VALLÉE 66, rue Saint-Joseph, Gracefield Tous les vendredis de 13h à 18h du 19 juin au 28 août 2020. Courriel : [email protected] Site web : www.lessaveursdelavallee.com Marché/Market Les Saveurs de la Vallée Le Marché Les Saveurs de la Vallée est le rendez-vous hebdomadaire des épicuriens fréquentant la Vallée-de-la-Gatineau. Il a pour mission de mettre en valeur le savoir-faire des producteurs de la région, ainsi que d’offrir la possibilité de déguster des aliments de saison, frais, locaux et de qualité, le tout dans une ambiance exceptionnelle ! The Les Saveurs de la Vallée Farmer’s Market is the weekly gathering of epicureans visiting the Vallée-de-la-Gatineau. -

Amends Letters Patent of Improvement Districts

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS AND HOUSING Local Government Act Ministerial Order No. M336 WHEREAS pursuant to the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. Reg 30/2010 the Local Government Act (the ‘Act’), the minister is authorized to make orders amending the Letters Patent of an improvement district; AND WHEREAS s. 690 (1) of the Act requires that an improvement district must call an annual general meeting at least once in every 12 months; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 further restrict when an improvement district must hold their annual general meetings; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 require that elections for board of trustee positions (the “elections”) must only be held at the improvement district’s annual general meeting; AND WHEREAS the timeframe to hold annual general meetings limits an improvement district ability to delay an election, when necessary; AND WHEREAS the ability of an improvement district to hold an election separately from their annual general meeting increases accessibility for eligible electors; ~ J September 11, 2020 __________________________ ____________________________________________ Date Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (This part is for administrative purposes only and is not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Act and section: Local Government Act, section 679 _____ __ Other: Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, OIC 50/2010_ Page 1 of 7 AND WHEREAS, I, Selina Robinson, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, believe that improvement districts require the flexibility to hold elections and annual general meetings separately and without the additional timing restrictions currently established by their Letters Patent; NOW THEREFORE I HEREBY ORDER, pursuant to section 679 of the Act and the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. -

![Document 6A. Carte De Défavorisation Outaouais [ PDF ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3933/document-6a-carte-de-d%C3%A9favorisation-outaouais-pdf-813933.webp)

Document 6A. Carte De Défavorisation Outaouais [ PDF ]

MRC La Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 7 Bois-Franc, Montcerf -Lytton, Grand-Rem ous Réservoir 8 Aum ond, Déléag e Baskatong 9 Maniwaki, Eg an Sud 10 Kitig an Zibi 11 Blue Sea, Bouch ette, Messines, Sainte-Th érèse-de-la-Gatineau 12 Kazabazua, Lac-Sainte-Marie, Low, Alleyn-et-Cawood 7 13 Gracef ield, Cayam ant MRC Papineau MMRRCC LLaa 28 Notre-Dam e-de-la-Salette, Bowm an, Val-des-Bois VVaallllééee--ddee--llaa--GGaattiinneeaauu 29 L'Ang e-Gardien Est, Mayo, Mulg rave-et-Derry 30 Ch énéville, Lac-Sim on, Duh am el 31 Saint-Sixte, Ripon, Montpellier 9 32 Th urso, Loch aber Est, Loch aber Ouest 8 33 Saint-André-Avellin R i v 34 Papineauville, Plaisance i MMRRCC PPoonnttiiaacc 10 è r Notre-Dam e-de-la-Paix, Nam ur, Boileau, Saint-Ém ile-de-Suf f olk, e 35 G Lac-des-Plag es a t i n 36 Montebello, Fassett, Notre-Dam e-de-Bonsecours e a u 11 Lac des Ri vièr Trente et ede s O Un Milles ut ao Lac ua is 2 13 Gagnon Lac du 30 3 Poisson Blanc Lac Simon MRC Pontiac 35 5 12 Rapides-des-Joach im s, Sh eenboro, 2 Lac 28 MMRRCC PPaappiinneeaauu Ch ich ester, W alth am , L’Isle-aux-Allum ettes Sainte-Marie Réservoir 3 Mansf ield-et-Pontef ract, Fort-Coulong e l'Escalier Litch f ield, L’Île-du-Grand-Calum et, Cam pbell’s Bay, 31 4 4 Bryson 21 29 5 Th orne, Otter Lake 14 27 36 6 Sh awville, Portag e-du-Fort, Clarendon MMRRCC LLeess 33 CCoolllliinneess--ddee--ll''OOuuttaaoouuaaiiss MRC Les Collines-de-l'Outaouais 15 24 34 14 La Pêch e Ouest - Secteurs : Lac-des-Loups, East Aldf ield et Duclos 6 19 22 32 15 La Pêch e Centre - Secteurs : Sainte-Cécile-de-Mash am , Rupert