Introduction One Setting the Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

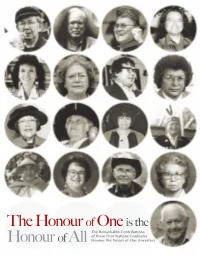

The Honour of One Is the the Remarkable Contributions of These First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors Table of Contents of Table

The Honour of One is the The Remarkable Contributions of these First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Introduction 4 William (Bill) Ronald Reid 8 George Manuel 10 Margaret Siwallace 12 Chief Simon Baker 14 Phyllis Amelia Chelsea 16 Elizabeth Rose Charlie 18 Elijah Edward Smith 20 Doreen May Jensen 22 Minnie Elizabeth Croft 24 Georges Henry Erasmus 26 Verna Jane Kirkness 28 Vincent Stogan 30 Clarence Thomas Jules 32 Alfred John Scow 34 Robert Francis Joseph 36 Simon Peter Lucas 38 Madeleine Dion Stout 40 Acknowledgments 42 4 THE HONOUR OF ONE IntroductionIntroduction 5 THE HONOUR OF ONE The Honour of One is the Honour of All “As we enter this new age that is being he Honour of One is the called “The Age of Information,” I like to THonour of All Sourcebook is think it is the age when healing will take a tribute to the First Nations men place. This is a good time to acknowledge and women recognized by the our accomplishments. This is a good time to University of British Columbia for share. We need to learn from the wisdom of their distinguished achievements and our ancestors. We need to recognize the hard outstanding service to either the life work of our predecessors which has brought of the university, the province, or on us to where we are today.” a national or international level. Doreen Jensen May 29, 1992 This tribute shows that excellence can be expressed in many ways. -

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature Jeroen G. Zandberg Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature 1. Introduction Page 3 2. How do I define a negative biased statement? …………………..5 3. The various statements ……………………………………… 6 3.1 Huibregtse ……………………………………… ……. 6 3.2 DeWaldt ……………………………………………. 9 3.3 Barnard ……………………………………………. 12 3.4 Weiss ……………………………………………. 16 4. The consequences of the statements ………………………… 26 4.1 Membership application to the UNPO ……………27 4.2 United Nations ………………………………………29 4.3 Namibia ……………………………………………..31 4.4 Baster political identity ………………………………..34 5. Conclusion and recommendation ……………………………...…38 Bibliography …………………………………………………….41 Rehoboth journey ……………………………………………...43 Picture on front cover: The Kapteins Council in 1876. From left to right: Paul Diergaardt, Jacobus Mouton, Hermanus van Wijk, Christoffel van Wijk. On the table lies the Rehoboth constitution (the Paternal Laws) Jeroen Gerk Zandberg 2005 ISBN – 10: 9080876836 ISBN – 13: 9789080876835 2 1. Introduction The existence of a positive (self) image of a people is very important in the successful struggle for self-determination. An image can be constructed through various methods. This paper deals with the way in which an incorrect image of the Rehoboth Basters was constructed via the literature. Subjects that are considered interesting or popular, usually have a great number of different publications and authors. A large quantity of publications almost inevitably means that there is more information available on that specific topic. A large number of publications usually also indicates a great amount of authors who bring in many different views and interpretations. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR the Rehoboth Rebellion

The Gubblns Library, AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR The Rehoboth Rebellion by P. Pearson At dawn on the 5th of April 1925, a force of 621 men comprising citizen force troops and police surrounded the town of Rehoboth in South West Africa. Their object was to secure the arrest of three men who had failed to respond to summonses issued under the stock branding proclamation. Seven days previously a large group of supporters had prevented three local policemen from entering the building where the men were staying. In response to this act of defiance, the Administrator had mobilized the citizen force in nine districts and declared (2) martial law in Rehoboth. At 7am a messenger entered the town carrying an ultimatum from Col. de Jager, commander of the troops. It called for an unconditional surrender by 8am. The rebels asked for more time in order to evacuate the women and children, but at 8.15am three aeroplanes fitted with machine guns flew low over the town and the soldiers charged. Faced with this vastly superior force, the rebels offered little resistance, and no shots were fired. The soldiers and policemen were spurred on by de Jager to attack their opponents with sticks arid rifle butts. Women and children who surrounded the rebel headquarters in an attempt to (4) protect their menfolk inside were also quickly dealt with in this way. Six hundred and thirty two people were arrested on charges of illegal assembly and 304 firearms were confiscated. All of the weapons were subsequently declared 'unservicablef and destroyed. Organised resistance had begun some twenty months earlier on the 17th of August 1923. -

Socio-Historical Classification of Khoekhoe Groups

Socio-historical classification of Khoekhoe groups Tom Güldemann & Alena Witzlack-Makarevich (Humboldt University Berlin, University of Kiel) Speaking (of) Khoisan: A symposium reviewing southern African prehistory EVA MPI Leipzig, 14–16 Mai 2015 1 Kolb 1719 Overview • Introduction • Khoekhoe groups • in pre- and early colonial period • in later colonial periods • today • Problems and challenges 2 Introduction • The Khoekhoe played an important role in the network of language contact in southern Africa a) because of their traditionally mobile economies → larger migratory territories b) contact with all language groups in the area . Tuu languages as the earliest linguistic layer . Bantu languages (Herero, Tswana, Xhosa) . colonial languages: Dutch → influencing Afrikaans 3 Introduction • The Khoekhoe played an important role in the network of language contact in southern Africa a) traditionally mobile → larger migratory territories b) contact with all language groups in the area c) fled from the encroaching colonial system carrying with them their Khoekhoe language + Dutch and some cultural features → considerable advantages and prestige vis-à-vis the groups they encounter during their migrations 4 Introduction • The Khoekhoe language played a dual role: o the substratum of groups shifting to other languages (e.g. Dutch/Afrikaans) o the target of language shift by groups speaking other languages • complexity unlikely to be disentangled completely • especially problematic due to the lack of historical linguistic data → wanted: a more fine-grained -

Ethnic Conflict and International Law : Group Claims and Conflict Resolution Within the International Legal System

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2006 Ethnic conflict and international law : group claims and conflict resolution within the international legal system Kempin Reuter, Tina Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-163530 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Kempin Reuter, Tina. Ethnic conflict and international law : group claims and conflict resolution within the international legal system. 2006, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Ethnic Conflict and International Law Group Claims and Conflict Resolution within the International Legal System Abhandlung zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultt der Universitt Zürich vorgelegt von Tina empin von Mnnedorf und Uetikon ZH Angenommen im Wintersemester 2006/2007 auf Antrag von Herrn Prof. Dr. urt R. Spillmann und Herrn Prof. Dr. Daniel Thürer. Studentendruckerei Zürich. 2006 Table of Contents Acknowledgments..........................................................................................................................iii Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................vi Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 -

“In Principle”: Sto:Lo Political Organizations and Attitudes Towards Treaty Since 1969

“In Principle”: Sto:lo Political Organizations and Attitudes Towards Treaty Since 1969 By Byron Plant Term Paper History 526 May 6 - June 7 2002 Sto:lo Ethnohistory Field School Instructors: Dr. John Lutz and Keith Carlson Due: Friday, 5 July 2002 1 This essay topic was initially selected from those compiled by the Sto:lo Nation and intended to examine Sto:lo attitudes towards treaty since 1860. While certainly a pertinent and interesting question to examine, two difficulties arose during my initial research. One was the logistical question of condensing a century and a half of change into such a short paper while at the same time giving due consideration to the many social, political, and economic changes of that time. Two, little to no work has been done on tracing how exactly Sto:lo political attitudes have been voiced over time. While names such as the East Fraser District Council, Chilliwack Area Indian Council, and Coqualeetza regularly appear throughout documentary and oral sources, no one has actually outlined what these organizations were, why they formed, and where they went. Consequently, through consultation and several revisions with Dave Smith, Keith Carlson, and John Lutz, the scope of the paper was narrowed down to the period from 1969 to the present and opened up to questions about Sto:lo political and administrative organizations. Through study of the motivations, ideals, and legacies of these organizations and their participants, I hope to then examine treaty attitudes and to what extent treaties influenced Sto:lo political activity over the past thirty years. In hindsight, I can see how study of any individual Sto:lo organization is capable of constituting a full paper in itself. -

1 Ethnic Stratification and the Equilibrium of Inequality: Ethnic

Ethnic Stratification and the Equilibrium of Inequality: Ethnic Conflict in Post-colonial States Manuel Vogt 13,937 words 1 Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank Lars-Erik Cederman, Carles Boix, Paul Huth, Nils-Christian Bor- mann, Dan Siegel, Matthijs Bogaards, Tom Pavone, Mark Beissinger, Simon Hug, as well as three anonymous reviewers of the journal for their valuable comments and suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to the participants of the Race, Ethnicity, and Identity workshop at Princeton University and the University of Maryland colloquium where I presented this work. The data used in this article can be accessed on the journal’s replication website. 2 Manuel Vogt ETH Zürich [email protected] 3 Ethnic Stratification and the Equilibrium of Inequality: Ethnic Conflict in Post-colonial States Manuel Vogt Why are ethnic movements more likely to turn violent in some multiethnic countries than in oth- ers? Focusing on the long-term legacies of European overseas colonialism, this article investi- gates the effect of distinct ethnic cleavage types on the consequences of ethnic group mobiliza- tion. It argues that the colonial settler states and other stratified multiethnic states are charac- terized by an equilibrium of inequality, in which historically marginalized groups lack both the organizational strength and the opportunities for armed rebellion. In contrast, ethnic mobiliza- tion in the decolonized states and other segmented multiethnic societies is more likely to trigger violent conflict. The paper tests these arguments in a global quantitative study from 1946 to 2009, using new data on the linguistic and religious segmentation of ethnic groups. -

Community Economic Development ~ Indigenous Engagement Strategy for Momentum, Calgary Alberta 2016

Community Economic Development ~ Indigenous Engagement Strategy for Momentum, Calgary Alberta 2016 1 Research and report prepared for Momentum by Christy Morgan and Monique Fry April 2016 2 Executive Summary ~ Momentum & Indigenous Community Economic Development: Two worldviews yet working together for change Momentum is a Community Economic Development (CED) organization located in Calgary, Alberta. Momentum partners with people living on low income to increase prosperity and support the development of local economies with opportunities for all. Momentum currently operates 18 programs in Financial Literacy, Skills Training and Business Development. Momentum began the development of an Indigenous Engagement Strategy (IES) in the spring of 2016. This process included comparing the cultural elements of the Indigenous community and Momentum’s programing, defining success, and developing a learning strategy for Momentum. Data was collected through interviews, community information sessions, and an online survey. The information collected was incorporated into Momentum’s IES. Commonalities were identified between Momentum’s approach to CED based on poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods, and an Indigenous CED approach based on cultural caring and sharing for collective wellbeing. Both approaches emphasize changing social conditions which result in a community that is better at meeting the needs of all its members. They share a focus on local, grassroots development, are community orientated, and are holistic strength based approaches. The care taken by Momentum in what they do and how they do it at a personal, program and organizational level has parallels to the shared responsibility held within Indigenous communities. Accountability for their actions before their stakeholders and a deep-rooted concern for the wellbeing of others are keystones in both approaches. -

Economic and Social Council in Its Resolution 1982/34 of 7 May 1982

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/17 9 August 2001 Original: ENGLISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights Fifty-third session Agenda item 5 (b) PREVENTION OF DISCRIMINATION Prevention of discrimination and protection of indigenous peoples Report of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations on its nineteenth session Chairperson-Rapporteur: Ms. Erica-Irene Daes GE.01-14979 (E) E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/17 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 - 3 4 I. ORGANIZATION OF THE WORK OF THE SESSION ..... 4 - 16 5 A. Attendance ...................................................................... 4 - 5 5 B. Documentation ............................................................... 6 5 C. Opening of the session .................................................... 7 5 D. Election of officers ......................................................... 8 - 10 5 E. Adoption of the agenda ................................................... 11 - 15 6 F. Adoption of the report .................................................... 16 6 II. REVIEW OF DEVELOPMENTS PERTAINING TO THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND THEIR RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT, INCLUDING THEIR RIGHT TO PARTICIPATE IN DEVELOPMENT AFFECTING THEM.............................................................. 17 - 78 7 III. REVIEW -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Apperception and Linguistic Contact between German and Afrikaans Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr6157f Author Bergerson, Jeremy Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Apperception and Linguistic Contact between German and Afrikaans By Jeremy Bergerson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Irmengard Rauch, Co-Chair Professor Thomas Shannon, Co-Chair Professor John Lindow Assistant Professor Jeroen Dewulf Spring 2011 1 Abstract Apperception and Linguistic Contact between German and Afrikaans by Jeremy Bergerson Doctor of Philosophy in German University of California, Berkeley Proffs. Irmengard Rauch & Thomas Shannon, Co-Chairs Speakers of German and Afrikaans have been interacting with one another in Southern Africa for over three hundred and fifty years. In this study, the linguistic results of this intra- Germanic contact are addressed and divided into two sections: 1) the influence of German (both Low and High German) on Cape Dutch/Afrikaans in the years 1652–1810; and 2) the influence of Afrikaans on Namibian German in the years 1840–present. The focus here has been on the lexicon, since lexemes are the first items to be borrowed in contact situations, though other grammatical borrowings come under scrutiny as well. The guiding principle of this line of inquiry is how the cognitive phenonemon of Herbartian apperception, or, Peircean abduction, has driven the bulk of the borrowings between the languages.