Socio-Historical Classification of Khoekhoe Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism in the Context of the Afrikaner Nationalist Ideology

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 78, 2009, 2, 305-323 CALVINISM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE AFRIKANER NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY Jela D o bo šo vá Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] Calvinism was a part of the mythic history of Afrikaners; however, it was only a specific interpretation of history that made it a part of the ideology of the Afrikaner nationalists. Calvinism came to South Africa with the first Dutch settlers. There is no historical evidence that indicates that the first settlers were deeply religious, but they were worshippers in the Nederlands Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church), which was the only church permitted in the region until 1778. After almost 200 years, Afrikaner nationalism developed and connected itself with Calvinism. This happened due to the theoretical and ideological approach of S. J.du Toit and a man referred to as its ‘creator’, Paul Kruger. The ideology was highly influenced by historical developments in the Netherlands in the late 19th century and by the spread of neo-Calvinism and Christian nationalism there. It is no accident, then, that it was during the 19th century when the mythic history of South Africa itself developed and that Calvinism would play such a prominent role in it. It became the first religion of the Afrikaners, a distinguishing factor in the multicultural and multiethnic society that existed there at the time. It legitimised early thoughts of a segregationist policy and was misused for political intentions. Key words: Afrikaner, Afrikaner nationalism, Calvinism, neo-Calvinism, Christian nationalism, segregation, apartheid, South Africa, Great Trek, mythic history, Nazi regime, racial theories Calvinism came to South Africa in 1652, but there is no historical evidence that the settlers who came there at that time were Calvinists. -

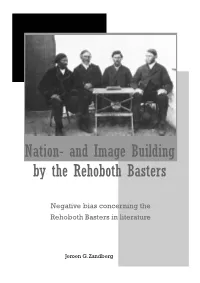

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters

Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature Jeroen G. Zandberg Nation- and Image Building by the Rehoboth Basters Negative bias concerning the Rehoboth Basters in literature 1. Introduction Page 3 2. How do I define a negative biased statement? …………………..5 3. The various statements ……………………………………… 6 3.1 Huibregtse ……………………………………… ……. 6 3.2 DeWaldt ……………………………………………. 9 3.3 Barnard ……………………………………………. 12 3.4 Weiss ……………………………………………. 16 4. The consequences of the statements ………………………… 26 4.1 Membership application to the UNPO ……………27 4.2 United Nations ………………………………………29 4.3 Namibia ……………………………………………..31 4.4 Baster political identity ………………………………..34 5. Conclusion and recommendation ……………………………...…38 Bibliography …………………………………………………….41 Rehoboth journey ……………………………………………...43 Picture on front cover: The Kapteins Council in 1876. From left to right: Paul Diergaardt, Jacobus Mouton, Hermanus van Wijk, Christoffel van Wijk. On the table lies the Rehoboth constitution (the Paternal Laws) Jeroen Gerk Zandberg 2005 ISBN – 10: 9080876836 ISBN – 13: 9789080876835 2 1. Introduction The existence of a positive (self) image of a people is very important in the successful struggle for self-determination. An image can be constructed through various methods. This paper deals with the way in which an incorrect image of the Rehoboth Basters was constructed via the literature. Subjects that are considered interesting or popular, usually have a great number of different publications and authors. A large quantity of publications almost inevitably means that there is more information available on that specific topic. A large number of publications usually also indicates a great amount of authors who bring in many different views and interpretations. -

A Look at the Coloured Community

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS JCB-10- A Look at the 16 Dan Pienaaz Road Coloued Commun_ ty Duzban, Nat al Republic of South Africa June 1st, 1962 Ir. Richard Nolte Institute of Current World Affairs 66 ladison Avenue New York 17, Iew York Dear ir. Nolte: There are many interesting parallels between the South African Coloured people and the Nnerican Negro. Each is a group today only because colour singles them out for dis- crimination. They each have developed a culture that has little in common with that of the tribal African. And perhaps their most striking s iw.ilarity'lies in their mutual desire for full cit.zenship in their respective countries. However, while the position of the Negro ]as improved considerably in the last fifteen years the opposite has been true in South Africa. e Coloured population has not yet reached tle toint where they have a strong group consciousness, nor do they have the hope of a national government implementing a consti- tution in which their rights are fully guaranteed. They lack what ot-er South African racial groups have and that is a distinct cultural identity of their own. Their culture is that of the White South African, especially the Afrikaner. Even the Cape Malays, who with trei: loslem faith are about the most 'foreign' of the Coloureds, speak Afrikaans. Because there is so little difference in culture, light skins have made possible easy entry into the hite community. One social worker estimates that in recent years 25,000 have left the Cape to establish White identities in the Transvaal. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, and EMPIRE: a PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, AND EMPIRE: A PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R. Stromberg* As we approach the centennial of the Second Anglo–Boer War (Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, or “Second War for Freedom”), reassessment of the South African experience seems in order. Whether the recent surrender by Afrikaner political leaders of their “central theme” and the dismantling of their grandiose Apartheid state will lead to heaven on earth (as some of the Soweto “comrades” expected), or even to a merely tolerable multiracial polity, remains in doubt. Historians have tended to look for the origins of South Africa’s “very strange society” in the interaction of various peoples and political forces on a rapidly changing frontier, especially in the 19th century. APPROACHES TO SOUTH AFRICAN FRONTIER HISTORY At least two major schools of interpretation developed around these issues. The first, Cape Liberals, viewed the frontier Boers largely as rustic ruffians who abused the natives and disrupted or- derly economic progress only to be restrained, at last, by humani- tarian and legalistic British paternalists. Afrikaner excesses, therefore, were the proximate cause and justification of the Boer War and the consolidation of British power over a united South Africa. The “imperial factor” on this view was liberal and pro- gressive in intent if not in outcome. The opposing school were essentially Afrikaner nationalists who viewed the Boers as a uniquely religious people thrust into a dangerous environment where they necessarily resorted to force to overcome hostile African tribes and periodic British harassment. The two traditions largely agreed on the centrality of the frontier, but differed radically on the villains and heroes.1 Beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, a third position was heard, that of younger “South Africanists” driven to distraction (and some *Joseph R. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR the Rehoboth Rebellion

The Gubblns Library, AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE SEMINAR The Rehoboth Rebellion by P. Pearson At dawn on the 5th of April 1925, a force of 621 men comprising citizen force troops and police surrounded the town of Rehoboth in South West Africa. Their object was to secure the arrest of three men who had failed to respond to summonses issued under the stock branding proclamation. Seven days previously a large group of supporters had prevented three local policemen from entering the building where the men were staying. In response to this act of defiance, the Administrator had mobilized the citizen force in nine districts and declared (2) martial law in Rehoboth. At 7am a messenger entered the town carrying an ultimatum from Col. de Jager, commander of the troops. It called for an unconditional surrender by 8am. The rebels asked for more time in order to evacuate the women and children, but at 8.15am three aeroplanes fitted with machine guns flew low over the town and the soldiers charged. Faced with this vastly superior force, the rebels offered little resistance, and no shots were fired. The soldiers and policemen were spurred on by de Jager to attack their opponents with sticks arid rifle butts. Women and children who surrounded the rebel headquarters in an attempt to (4) protect their menfolk inside were also quickly dealt with in this way. Six hundred and thirty two people were arrested on charges of illegal assembly and 304 firearms were confiscated. All of the weapons were subsequently declared 'unservicablef and destroyed. Organised resistance had begun some twenty months earlier on the 17th of August 1923. -

Forced Removal of Population the Apartheid Regime Has Sought to Enforce Strict Territorial Segregation of the Different ‘Population Groups’

residence, commercial activities and industry for members of the White, Coloured and Asian groups (each in separate zones). Based on these group areas are segregated local government structures, and a segregated tricameral parliament with separate White, Coloured and Indian chambers, designed to preserve white political power while extending limited participation in central government to small sections of the Indian and Coloured communities. The majority of the population in South Africa is united in rejecting the segregated political structures of apartheid. Forced Removal of Population The apartheid regime has sought to enforce strict territorial segregation of the different ‘population groups’. People are forcibly evicted from their homes if they are in a zone which the government has asigned to another group. The government speaks, not of forced removal or eviction, but of Relocation and Resettlement. The evictions take place in many different kinds of areas and under different laws. In rural areas people are moved on a number of different pretexts. The places in which they live may be designated Black Spots — these are areas of land occupied and owned by Africans which the government has designated for another group, usually white. The occupiers are moved to a bantustan. Others are moved in the course of Consolidation of the bantustans, as the regime attempts to reduce the number of fragments of land which make up the bantustans. Over a million black tenants have been evicted from white owned farms since the 1960s. Tenants who paid cash rent to the farms were called Squatters, implying they had no right to be on the land. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

McDonald, Jared. (2015) Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan identity and assimilation in the Cape Colony, c. 1795- 1858. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22831/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan Identity and Assimilation in the Cape Colony, c.1795-1858 Jared McDonald Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History 2015 Declaration for PhD Thesis I declare that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the thesis which I present for examination. -

Kaffraria, and Its Inhabitants

Afrjcana. a 0 SEP. 1940 I » Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from University of Pretoria, Library Services https://archive.org/details/kaffrariaitsinhaOOflem KAFFIR CHIEFS. KAFFRARIA, AND ITS INHABITANTS. XING WILLIAM’S TOWN. BY THE EEV. FRANCIS FLEMING, M.A., Chaplain to Her Majesty's Forces in King William's Town, British Kajfiaria. SECOND EDITION. LONDON: SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, AND CO., STATIONERS’ COURT; NORWICH: THOMAS PRIEST. MDCCCLIV. : MERENSKY-BIBLIOTEEK ( ■*! V E*SITI!T V A N m ETC* IA i ASNOMiilff 6 FLEMING | KiGiSTflUNOUMER-. ta.4» TO THE RIGHT REV. FATHER IN GOD, ROBERT GRAY, D.D., BY DIVINE PERMISSION, LORD BISHOP OF CAPE TOWN, THIS WORK IS INSCRIBED, NOT ONLY AS A MARK OF ESTEEM FOR HIS LORDSHIP’S UNWEARIED ZEAL AND ENERGY, IN BEHALF OF HIS PRESENT EXTENSIVE DIOCESE, BUT ALSO AS A SMALL, BUT SINCERE, TOKEN OF LOVE, GRATITUDE, AND AFFECTION, FOR MANY PERSONAL KINDNESSES RECEIVED BY THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. A few words will here suffice to describe the nature of the contents of the following pages. The part, performed by the pen, has been arranged from Notes, taken during a residence in Kaffirland of nearly three years. These notes were collected from personal observation, and inquiry, as well as from the reports of various individuals, long resident in the Cape Colony. I am much indebted to the Lord Bishop of Cape Town, for the use of some valuable information ; and also to the Honorable J. Godlonton, of Graham’s Town, the Rev. J. Appleyard, Wesleyan Missionary at King William’s Town, and various others in the Colony, for a similar boon. -

Afrikaners in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Inward Migration and Enclave Nationalism

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research Afrikaners in post-apartheid South Africa: Inward migration and enclave nationalism Author: South Africa’s transition to democracy coincided and interlinked with massive global shifts, 1 Christi van der Westhuizen including the fall of communism and the rise of western capitalist triumphalism. Late capitalism Affiliation: operates through paradoxical global-local dynamics, both universalising identities and 1Department of Sociology, expanding local particularities. The erstwhile hegemonic identity of apartheid, ‘the Afrikaner’, University of Pretoria, was a product of Afrikaner nationalism. Like other identities, it was spatially organised, with South Africa Afrikaner nationalism projecting its imagined community (‘the volk’) onto a national territory Corresponding author: (‘white South Africa’). The study traces the neo-nationalist spatial permutations of ‘the Christi van der Westhuizen, Afrikaner’, following Massey’s (2005) understanding of space as (1) political, (2) produced [email protected] through interrelations ranging from the global to micro intimacies, (3) potentially a sphere for heterogeneous co-existence, and (4) continuously created. Research is presented that shows a Dates: Received: 08 Feb. 2016 neo-nationalist revival of ethnic privileges in a defensive version of Hall’s ‘return to the local’ Accepted: 04 June 2016 (1997a). Although Afrikaner nationalism’s territorial claims to a nation state were defeated, Published: 26 Aug. 2016 neo-nationalist remnants reclaim a purchase on white Afrikaans identities, albeit in shrunken How to cite this article: territories. This phenomenon is, here, called Afrikaner enclave nationalism. Drawing on a Van der Westhuizen, C., global revamping of race as a category of social subjugation, a strategy is deployed that is here 2016, ‘Afrikaners in called ‘inward migration’.